This case shows an innovative method of double-segmental femur fracture, which is quite rare, and its fixation without the use of a fracture table, with some innovations, helps to raise awareness regarding alternative method where there are limitations.

Dr. Nischay Kaushik, Department of Orthopaedics, Dr. BSA Medical College and Hospital, New Delhi, India. E-mail: nikku1280@gmail.com

Introduction: Femoral fractures are undoubtedly common injuries, typically resulting from high-energy trauma in younger individuals or from bone fragility in older adults. However, fractures involving two or more regions of the femur are quite rare. These are usually caused by high-energy trauma and are classified as segmental femoral fractures (SFFs), which are described by us.

Case Report: A 35-year-old man with multiple-level femoral fractures at the subtrochanteric, diaphyseal, and supracondylar femoral regions – a condition known as double-SFFs – presented to our emergency department due motor vehicle collision. Intramedullary nailing was done without the use of a fracture table for fixation, and because there was a completely separated femoral fragment between the fracture lines, fracture reduction was difficult during reaming due rotation of the middle fragment.

Conclusion: Double-segmental femur fractures are regarded as exceedingly uncommon injuries. Our results highlight that intramedullary nailing without a fracture table can yield excellent functional outcomes, with patients expected to achieve full weight-bearing by four months and a full range of motion thereafter.

Keywords: Double-segmental, femur fracture, intramedullary nail.

With an annual incidence of 10–21 fractures per 100,000 patients and a 1-year death rate of 21%, femoral shaft fractures are quite a prevalent injury type [1]. They are brought on by low-energy mechanisms in older osteoporosis patients or high-energy trauma in young people [1]. Segmental femoral fractures (SFFs) are femur fractures that occur at two or more sites and are typically brought on by high-energy trauma, such as car crashes, falls from a height, and crush injuries [2]. Because of the many therapeutic options available, the individuality of each case, and the relatively high complication rates, managing SFFs is considered particularly critical [3]. Intramedullary nailing (IMN), plate and screw fixation, external fixation, or a combination of these are all potential therapeutic choices [4]. We describe a rare instance of a double SFF, a femur fracture that occurred at three separate sites and was treated at our facility. The purpose of this article is to highlight the difficulties our team faced in handling and treating this intricate situation. The patient was informed that data concerning the case would be submitted for publication, and he provided consent.

Pre-operative course

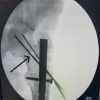

After being transferred from a rural community hospital following a traffic accident, a 35-year-old male patient arrived at our emergency department. There was no past medical history. Acute right limb pain and widespread thigh edema were discovered during the initial clinical evaluation; there were no skin lacerations, and there was clear deformity. There was no evidence of neurovascular dysfunction. Multiple femoral fractures at the subtrochanteric, diaphyseal, and supracondylar regions were visible on plain radiographs of the pelvis and right femur as shown in (Fig. 1). The proximal bone section was anterolaterally displaced due to an oblique subtrochanteric fracture. In addition, a transverse fracture with anteromedial displacement of a comminuted fragment was observed in the diaphyseal area. Finally, a transverse fracture in the supracondylar area with a flexed distal fragment. Vital signs were stable; hemoglobin (Hb) was 10.2 g/dL (normal 13.5–17.5), and the hematocrit (HCT) was 30.2% (normal 40–54%) at admission. Due to the patient’s HCT falling to 27.3% (Hb = 9.3 g/dL), a single packed red blood cell (RBC) transfusion was performed on the 2nd day of hospitalization. After written and informed consent and after clearance from anesthesia patient was planned for surgery.

Intraoperative course

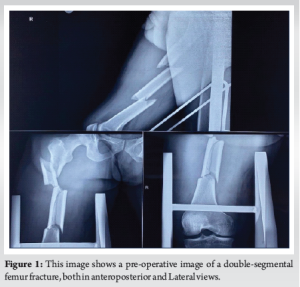

We determined that IMN was the best course of action after carefully weighing our treatment alternatives. The tibia skeletal traction was removed before the procedure, and the patient was placed under spinal anesthesia while lying supine on a standard radiolucent table. The innovative technique used was putting the patient in a supine position over the wooden footsteps and mattress, and keeping the normal limb in lithotomy position, we could get proper anteroposterior (AP) and lateral images without using the fracture table, it not only saves time which is generally used while connecting traction instruments it also helps which there are limitations or where fracture table is not available as shown in (Fig. 2). For osteosynthesis, a trochanteric antegrade nail was utilized. The required rotation and traction were manually applied intraoperatively. To insert a standardized awl into the greater trochanter’s tip, a typical lateral incision was created above the greater trochanter’s level following normal aseptic skin preparation and with the constant assistance of an image intensifier. The intramedullary guidewire was advanced to the level of the lesser trochanter. Incision was extended till the second fractured fragment, and TFL was cut to expose the fracture site. Multiple Hohmann retractors were used to align the first and second fractured fragments, which was difficult due to muscle pull at the proximal fragment and the displaced second fragment. The guide wire was passed through it till the second fractured fragment. The guide wire with a bent tip was then manipulated using a T-handle to pass through the third fractured fragment. The fourth and final fractured fragment was reduced using a bolster under the thigh, and a guide wire was passed till the superior border of the patella was centered in the coronal and sagittal planes under image intensifier guidance. Meticulous serial reaming of the femoral canal was then initiated using canulated manual reamers while maintaining reduction and rotation of fractured fragments under image intensifier guidance. After vigilant reaming, the nail was inserted into the femoral canal, followed by the timely insertion of central and peripheral screws. The patient received an additional unit of packed RBCs during surgery.

Post-operative course

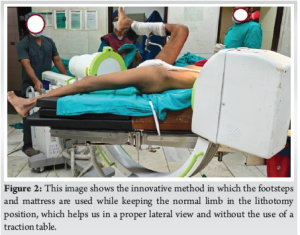

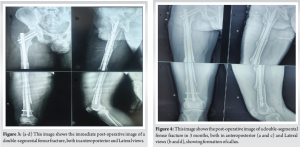

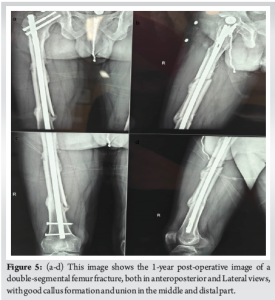

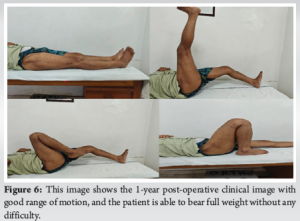

Since Hb was 8.1 g/dL and HCT was 24.5%, the patient received an additional unit of packed RBCs on the 1st post-operative day and X-ray was done as shown in (Fig. 3). On the 2nd post-operative day, in-bed turning, active quadriceps, hamstrings, and ankle pump was initiated, and on the 5th post-operative day, he was allowed to touch down while bearing weight. Using a walker, partial weight-bearing was started on the 10th post-operative day. After being admitted to the hospital for 11 days, the patient was released. During his hospital stay, no other issues were observed. He was told to attend physiotherapy sessions after being released from the hospital, and several routine follow-up appointments were planned. Bone union was assessed using both radiological and clinical parameters throughout the follow-up period, after 3 months (Fig. 4) shows good callus formation. The knee range of motion after 90 days was adequate (full knee extension and up to 115° of flexion), and callus formation was noted at the 3-month follow-up visit. Ultimately, 120 days after surgery, he was able to bear his entire weight without help. The patient cautiously resumed his pre-fracture activities after radiological evaluations at the 6- and 9-month follow-up visits showed satisfactory fracture healing. During the 12-month follow-up period, the patient was completely content with the functionality of his limbs and was able to go about his everyday activities without experiencing any problems (Fig. 5 and 6).

SFFs with three distinct fracture sites are extremely rare high-energy trauma injuries. Because they completely divide the bone segments, they are different from trifocal fractures [5]. Our report’s complete separation of bone cortex and malalignment makes this case even more rigorous, even though there aren’t many recorded cases of trifocal femoral fractures [6,7]. As far as we are aware, there have only been five instances of “double segmental” femur fractures documented in the body of the present literature [5,8,9]. Even though published research indicates that treating SFFs with different implants produces positive results, it only discusses situations in which femoral neck and shaft fractures coexist [10]. According to a recent study by Kook et al., [11] SFFs had a significantly higher non-union rate than non-SFFs, with residual fracture gaps and insufficient intramedullary nail canal filling being the main causes of non-union rates. In addition, a small-scale study by Liu et al., [2] indicated that combining plate fixation and IMN seems to be a successful strategy for the surgical treatment of SFFs with reduced operating time and high union rates. However, since there are so few solid results in the literature currently in publication, it is impossible to obtain reliable results in terms of the surgical treatment of double SFFs. Galanis et al., [12] in his study double double-segmental fracture showed fracture fixation using fracture table but, in our study, we showed fixation without use of fracture table with good results due to some limitations. Finally, given the complexity of these fractures and the wide range of available treatments, it is critical to emphasize that when treating double SFFs, doctors must always give patients all relevant information about the possible risks, advantages, and particular benefits of each procedure in comparison to the others. In this regard, doctors have a professional obligation to accurately explain the risks, advantages, and potential alternatives to a particular surgery while performing an informed consent process. In our instance, the patient received a thorough explanation of our team’s reasoning for the chosen course of therapy both before the procedure and throughout the informed consent procedure.

This case highlights the considerable exigency of treating double SFFs, which are underreported in the existing literature. Since each case is unique, without a fracture table, orthopedic surgeons should carefully weigh all potential fixation options while considering the specific characteristics of these injuries. As long as the double-segmental fracture is closed and the possible soft tissue injury is controllable, the primary course of action in these patients should be to operate on the femur’s pertinent IMN. In addition, it is crucial to emphasize that trauma surgeons should hone and improve their mini-open surgical procedures because doing an appropriate IMN for the treatment of a double SFF may call for the use of these abilities.

This case highlights the particularly challenging nature of managing double-SFFs, which remain underreported in the present literature. Orthopedic surgeons must carefully evaluate all fixation options, considering the unique characteristics of each injury. IMN should be the preferred approach when the fracture is closed and soft tissue damage is controllable. In addition, it is crucial for trauma surgeons to refine their mini-open surgical techniques, as performing an appropriate IMN for double SFFs may necessitate the use of these skills.

References

- 1.Enninghorst N, McDougall D, Evans JA, Sisak K, Balogh ZJ. Population-based epidemiology of femur shaft fractures. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1516-20. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Liu H, Wu J, Lin D, Lian K, Luo D. Results of combining intramedullary nailing and plate fixation for treating segmental femoral fractures. ANZ J Surg 2019;89:325-8. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Ferreira N, Britz E, Gould A, Harrison WD. The management of segmental femur fractures: The radiographic ‘cover-up’ test to guide decision making. Injury 2022;53:2865-71. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Adeel M, Zardad S, Jadoon SM, Younas M, Shah U. Outcome of open interlocking nailing in closed fracture shaft of femur. J Ayub Med Coll Abbottabad 2020;32:546-50. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bansal N, Singh G, Tiwari P, Kaur H. Double trouble of “double segmental” fractures - a report of two cases. J Orthop Case Rep 2022;12:30-3. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Griffin M, Dick AG, Umarji S. Outcomes after trifocal femoral fractures. Case Rep Surg 2014;2014:528061. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Papaioannou I, Baikousis A, Korovessis P. Trifocal femoral fracture treated with an intramedullary nail accompanied with compression bolts and lag screws: Case presentation and literature review. Cureus 2020;12:e8173. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Loganathan S, Thiyagarajan U. Multilevel segmental femur fracture in young individuals treated by a single step - all in one intramedullary device - a prospective study. Biomedicine 2021;40:488-91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Velmurugeasn, Durga Prasad V, Dheenadhayalan J, Rajasekaran S. Double segmental femur fracture: Two case reports with a technical note and perioperative illustration. Int J Orthop Sci 2020;6:618-21. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wei YP, Lin KC. Dual-construct fixation is recommended in ipsilateral femoral neck fractures with infra-isthmus shaft fracture: A STROBE compliant study. Medicine (Baltimore) 2021;100:e25708. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kook I, Park KC, Kim DH, Sohn OJ, Hwang KT. A multicenter study of factors affecting nonunion by radiographic analysis after intramedullary nailing in segmental femoral shaft fractures. Sci Rep 2023;13:7802. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Galanis A, Vavourakis M, Karampitianis S, Karampinas P, Sakellariou E, Tsalimas G, et al. Double segmental femoral fracture: A rare injury following high-energy trauma. J Med Cases 2024;15:297-303. [Google Scholar]