“DLO is a perferable to OWHTO in large varus deformities with better functional outcomes and fewer complications”

Dr. Hari Kishore Potupureddy, Department of Orthopedics, Anil Neerukonda Hospital, NRI Institute of Medical Sciences, Sangivalasa, Visakhapatnam, Andhra Pradesh, India/Fellow, Department of Orthopedics, Murup Hospital, Changwon, South Korea. Email: harikishore87@gmail.com

Introduction: Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy (OWHTO) and double-level osteotomy (DLO) are commonly performed for correcting large varus knee deformities. This retrospective cohort study compares long-term functional outcomes, complication rates, and survival rates between these two techniques.

Materials and Methods: Sixty patients who underwent OWHTO (n = 32) or DLO (n = 28) for varus knee correction were evaluated. Outcome measures included the Knee Society Score (KSS) and KSS function score at 1, 5, and 10 years, with percentage improvements analyzed across intervals. Additional measures included hip–knee–ankle (HKA) alignment accuracy, complication rates, and survival rates. Trend analysis was based on 10-year data for OWHTO and 5-year data for DLO.

Results: DLO demonstrated significantly higher HKA correction accuracy and fewer complications compared to OWHTO, including reduced incidence of joint line obliquity (JLO) (P = 0.001), posterior tibial slope (PTS) change (P = 0.013), and worsening patellofemoral arthritis (PFA) (P = 0.03). KSS improvements were observed in both groups at all intervals, with DLO showing superior KSS Function scores, suggesting higher functional stability. Percentage improvement trends favoured DLO for specific outcomes over the long term.

Conclusion: DLO provides more accurate HKA alignment with lower complication rates in JLO, PFA, and PTS changes, while both procedures yield comparable overall KSS scores. The enhanced KSS Function outcomes with DLO indicate a potential clinical advantage in maintaining higher functional activity and patient satisfaction over time. These findings support the use of DLO for patients requiring precise correction of significant varus deformities with sustained functional benefits.

Keywords: Double-level osteotomy, open-wedge high tibial osteotomy, joint line obliquity, clinical outcome, long-term functional outcomes, knee osteotomy, complications.

Opening wedge high tibial osteotomy (OWHTO) is popular for its simplicity and effectiveness in redistributing load toward the lateral compartment, which can relieve symptoms and slow disease progression [1-3]. However, OWHTO may have limitations; studies report increased complications such as hinge fractures, posterior tibial slope (PTS) alterations, and excessive joint line obliquity (JLO) [4-11]. Previous research has laid the groundwork for understanding the relative strengths and limitations of OWHTO and DLO. Studies by Lee et al. and Song et al. [9] have shown that OWHTO effectively realigns varus deformities in mild-to-moderate cases; however, outcomes tend to decline in patients with severe deformities, largely due to its limited capacity for correcting joint line orientation and the increased risk of lateral instability in complex misalignments [8,9]. In contrast, DLO has emerged as a solution for complex varus deformities by offering simultaneous correction at both the tibial and femoral levels. Recent findings by Brown et al. demonstrated that DLO reduces the incidence of JLO and over-correction, thereby preserving joint mechanics and alignment stability [12-14]. Further, Kang et al. observed that patients undergoing DLO reported lower rates of functional deterioration at 5 years post-surgery compared to OWHTO, with significantly reduced rates of osteoarthritic progression [15]. This evidence underscores the importance of DLO in maintaining joint stability, particularly in active and younger patients who place higher functional demands on the knee [15]. DLO’s dual-level approach aims to achieve a more comprehensive alignment correction, which may reduce the risk of JLO and improve overall knee biomechanics [15,16]. In addition, DLO has demonstrated stable long-term functional outcomes and potentially better knee function as measured by the Knee Society Score (KSS) and KSS Function scores, especially in younger or more active patients [15,16]. Despite the potential advantages of DLO, there is limited evidence comparing its long-term effectiveness, complication rates, and functional outcomes to OWHTO, especially over a 5–10-year follow-up period. Furthermore, the differences in alignment accuracy and rates of degenerative progression between OWHTO and DLO have not been extensively quantified. This study aims to evaluate the effectiveness, complication rates, and alignment accuracy of these procedures to inform clinical decision making [15- 20].

Study design

This retrospective single-center comparative cohort study included 60 patients with complete data who underwent OWHTO (n = 32) or DLO (n = 28) for large varus knee deformity (≥10°) between 2007 and 2020 at Murup Hospital, which performs >100 osteotomies per year. This study is approved by the hospital ethics committe (File no. No.- MURUP/IEC/2024/005). Patients were followed up to date with a minimum follow-up period of 5 years. Inclusion criteria focused on patients with symptomatic varus malalignment ≥10° and significant medial compartment degeneration, confirmed radiographically. A functional anterior cruciate ligament (ACL), and failure of non-operative treatment. The exclusion criteria were knee instability, valgus knee deformity, knee osteoarthritis (OA) classified as Ahlback grade >3, history of previous osteotomies or trauma surgery around the knee, and patients with a history of any other serious medical conditions that could affect the clinical or functional outcomes. OWHTO group was matched with patients from the DLO group according to sex, age, body mass index (BMI), deformity (pre-operative hip-knee-ankle [HKA]), and function (pre-operative KSS function score). All patients were treated using the same standardized surgical technique in each group by a single senior osteotomy surgeon. From 2007 to 2016, OWHTO was performed for large varus deformities involving the femur and tibia or only tibia. Since 2017, DLO was adopted for larger varus corrections or with deformities involving both the femur and tibia.

DLO procedure

Lateral closing-wedge distal femoral osteotomy. Each patient was placed supine with a tourniquet placed proximally on the limb. A lateral femoral closing-wedge osteotomy [21,22] was performed with a 5–6-cm approach made at the lateral aspect of the thigh extending from the lateral epicondyle proximally. Under C-ARM, 2 guide pins were inserted starting from the lateral cortex to create a triangle with the hinge point angled toward the medial epicondyle and 1 cm away from the contralateral cortex, carefully to reduce the risk of hinge fracture. The 2 cuts were then made by sliding along the pins, and an anterior ascending cut was made once the biplanar cut was complete, the bone fragment between the 2 main cuts was extracted. To close the osteotomy, gentle pressure was applied on the foot in an axial direction until there was cortical contact on the lateral side. A distal femoral plate with 8 locking screws (4 epiphyseal above and 4 diaphyseal below the osteotomy) was applied to hold the osteotomy.

Medial OWHTO

A 5-cm longitudinal incision was performed distal to the medial joint line at the level of the pes anserinus; the medial tibia was exposed. A periosteal elevator was run along the posterior tibial cortex to create a safe passage for the neurovascular protector after performing a window posterior to the superficial medial collateral ligament [10]. Two guide pins were placed in the tibia at the metaphyseal flare parallel to the tibial slope. These were used to mark the upper border of the osteotomy and aimed toward a hinge point which is just above the the tips of the fibular head. After saw cuts for the osteotomy were made under fluoroscopic control, a biplane cut was made in an ascending fashion. The osteotomy site was opened under fluoroscopic control; a post-operative mechanical valgus angulation of 3–4 (mechanical femorotibial angle of 177 and weight bearing line located at 62–65% of tibial width and just lateral to lateral tibial spine) was anticipated, and full extension had to be achieved. Valgus correction was performed with the aim of achieving the correction which was pre-operative planned, a bone substitute tricalcium phosphate wedge was prepared according to the opening distance and inserted at the posteromedial corenr in the osteotomy opening matching the cortex of the tibia this was used in all cases; additionally the wedge removed from the distal femur was utilized as cancellous autograft in open wedge of tibia. In OWHTO, as exclusive procedure bonegraft was harvested from metaphyseal region of distal femur on medial side at the level of adductor tubercle using OATS punch and inserted in the osteotomy site. Medial high tibial plate (TomoFix Anatomical) with 8 locking screws (4 epiphyseal above and 4 diaphyseal below the osteotomy) was applied to hold the osteotomy open.

Rehabilitation

The same perioperative and post-operative protocols were used in both groups. Active and passive physical therapy including progressive range of motion, recovery and quadriceps, reactivation were started postoperatively.

Radiological analysis

Pre-operative and post-operative radiographs were reviewed from the data in the PACS PLUS by two reviewers blinded to treatment. These included a full-length, standing long-leg anteroposterior (AP) radiograph as well as short, standing AP and lateral knee radiographs. Knee computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI). Measurements were performed from these images using PACS PLUS software and included the HKA, medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA), lateral distal femoral angle (LDFA), PTS, and JLO for each knee, following the standard measurement protocols. In addition, arthroscopic images taken during diagnostic arthroscopy (done before osteotomy surgery as a standard protocol) and 1 year postop before the plate removal (2nd look arthroscopy) were analyzed to check the PFA and ACL condition

Clinical evaluation

Functional assessment of knees using the KSS and KSS Function Score was done preoperatively and postoperatively at 1, 5 years’ follow-up for both groups, and additionally for OWHTO group 10 years scores were also assessed.

Statistical analysis

Before initiation of the study, a power analysis was conducted to confirm that the sample size of 60 was sufficient to detect medium effect sizes (d = 0.5) with 80% power, thereby minimizing the risk of Type II errors. This power level was particularly important for detecting meaningful differences in primary outcomes such as KSS and complication rates. Data were reported as mean values with standard deviations or as counts with percentages. The t-test was done for pre-operative KSS and KSS Function scores between DLO and high tibial osteotomy (HTO) groups, results indicate that groups are not matched at baseline.

We calculated the improvement as follows:

KSS improvement = Post-operative KSS − Pre-operative KS

KSS function improvement = Pre-operative KSS function – Pre-operative KSS function

To ensure an accurate comparison between DLO and HTO groups, we used two methods to adjust for baseline differences: Percentage improvement for both KSS and KSS function score. This approach calculates relative improvement (improvement as a percentage of the pre-operative score at 1 year, 5 years and 10 years) to standardize the scores, making them more comparable across groups. KSS and KSS function percentage improvement was analyzed as a primary comparative measure at 1-year, 5-year, and 10-year follow-up points, providing insight into functional outcomes over time. In addition analysis of covariance (ANCOVA) for KSS improvement, a Mann–Whitney U-test for KSS function improvement were used for robustness of interpretation. To evaluate the variables between groups Mann–Whitney U-test was applied to non-normally distributed continuous data, including BMI and KSS scores, to compare median values between the OWHTO and DLO groups. The choice of a non-parametric test was based on preliminary assessments showing non-normal distribution of these variables, while ANCOVA adjusted for baseline demographics (age, BMI) in KSS improvement analysis. Fisher’s exact test evaluated categorical data with small frequencies (e.g., hinge fractures, worsened patellofemoral arthritis [PFA]), and HKA axis correction accuracy between groups. Two-way repeated measures analysis of variance (ANOVA) – the analysis was utilized for longitudinal data (e.g., KSS over 1, 5, and 10 years), allowing for within-group comparisons across time intervals while assessing differences between the OWHTO and DLO groups. Effect sizes, including Cohen’s d and Phi coefficient quantified the strength of findings and outcomes, enhancing the interpretability of findings in light of sample size constraints. As DLO group has only 5 years of follow-up, we have statistically projected its results to 10 years based on trend analysis. Patients were categorized by post-operative HKA valgus alignment as under-correction (post-operative HKA <1.5° valgus), over-correction (post-operative HKA >4°), and corrected (1.5°≤ post-operative HKA ≤4°). To compare JLO occurrence in both groups, patients were classified into the following categories based on their JLO values: No JLO (0–1°), Mild JLO (>1°–4°), Moderate JLO (>4°–6°), and Severe JLO (>6°). We further grouped these categories – Severe and Moderate JLO patients as “Significant JLO group,” Mild and no JLO patients as “Acceptable JLO group” for comparisons and to analyze how consistently each procedure maintained joint alignment. Based on pre-operative and 1-year post-operative, MRI and comparison of images of diagnostic arthroscopy done at index surgery and 1 year later (2nd look), based on the International Cartilage Repair Society grade. The distribution of PFA outcomes, categorized into Worsened and Not Worsened (either the same as pre-operative or improved), and compared between the OWHTO and DLO.

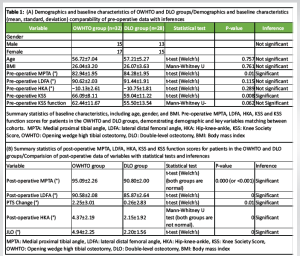

Demographics and baseline characteristics (Table 1)

No significant differences were found in age, gender, BMI, pre-operative LDFA (°), pre-operative HKA (°), pre-operative KSS function between the OWHTO and DLO groups (P > 0.05), indicating that both groups were matched in these characteristics while pre-operative MPTA and KSS were having significant difference, pre operative MPTA of OWHTO group will be expectedly less compared to DLO group as patients with more deformity in tibia side would be chosen for HTO (Table 1 summary statistics).

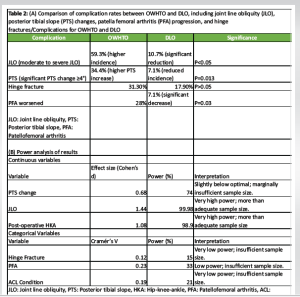

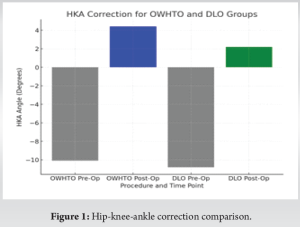

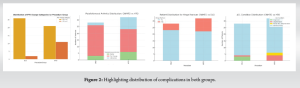

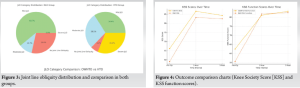

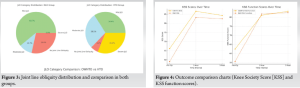

Complications and correction accuracy (Table 2 and Figs. 1, 2, 3)

HKA correction accuracy

In the OWHTO group, 19 patients were over-corrected, 9 achieved normal correction, and 4 were under-corrected. The DLO group showed more accurate HKA correction, with 16 achieving normal correction, 4 over-corrected and 8 under-corrected. Fisher’s exact test yielded a statistically significant difference (P = 0.036), with a large effect size (d = 1.08), favoring the DLO group for HKA correction accuracy. A significant P-value (P = 0.0005) also indicated a strong tendency toward over-correction in OWHTO (Fig. 1). These findings indicate that the DLO procedure achieves more precise HKA correction, with alignment closer to the desired neutral range. In contrast, the OWHTO procedure is associated with a significantly higher tendency toward over-correction (Fig 1).

JLO

In the DLO group, 17 patients showed Mild JLO, 3 cases showed moderate JLO, 8 with No JLO. Importantly, The DLO group showed a lower severity of JLO with no severe cases, while the OWHTO group had 10 cases of severe JLO (32.3%), 9 patients had moderate JLO, while 11 had mild JLO, and only 2 patients exhibited no JLO. Chi-square tests (χ² = 13.20, P < 0.001) and Mann–Whitney U results indicated greater consistency in maintaining acceptable JLO in the DLO group, with a moderate-to-large effect size (Phi = 0.469) (Figs. 2, 3).

PTS

In the DLO group, majority of patients (26 out of 28; 92.9%) experienced a PTS change of <4°, indicating minimal alteration in tibial slope post-procedure. A greater proportion of OWHTO patients experienced significant PTS changes (≥4°), with 34.4% compared to 7.1% in DLO. Fisher’s exact test showed a statistically significant difference (P = 0.013) (Fig. 2).

PFA

“Worsened” PFA was more common in OWHTO, with 9 cases versus 2 in DLO. A Fisher’s exact test revealed a statistically significant difference between the two groups in the rate of worsened PFA, with a P = 0.03. This suggests DLO is associated with more stable PFA outcomes (Figs. 2, 4).

ACL condition

In the DLO group, 24/28 patients (85.7%) no change in ACL condition, 3 patients showed improvement, and only 1 showed degeneration. OWHTO group 26/32 (81.3%) retained the same ACL condition as pre-operation, 4 had degeneration, 2 patients developed partial tears along with degeneration.While both groups retained similar ACL conditions post-operative, OWHTO showed more instances of ACL degeneration and partial tears, not statistically significant (P = 0.129) though (Fig. 2).

Hinge fracture incidence

DLO group, 5/28 patients (17.9%) had hinge fractures while in OWHTO group, 10/32 patients (31.3%) had hinge fracture, the P = 0.371 (not statistically significant). In addition, the low effect size implies that the observed difference in hinge fracture incidence may not be clinically meaningful, and the results should be interpreted with caution (Fig. 2).

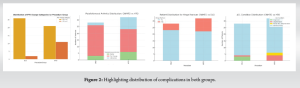

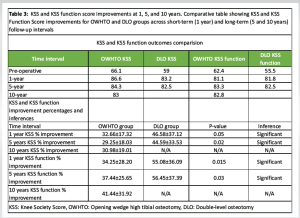

Functional outcome comparison (Table 3 and Fig. 4)

Short-term outcomes (1 year)

Both groups showed comparable KSS percentage improvements (P > 0.05), DLO showed significantly higher KSS functional percentage improvement than OWHTO (P = 0.017), as confirmed by the Mann–Whitney U test (P = 0.043).

Long-term outcomes (5 years)

A significant difference in KSS percentage improvement was found (P = 0.037), with DLO showing a marginal advantage. DLO also demonstrated superior KSS function percentage improvement (P = 0.028) confirmed by the Mann–Whitney U test (P = 0.047).

10-year outcomes (HTO group only)

KSS and KSS function scores: Repeated measures ANOVA indicated no significant change in KSS or KSS Function scores over time, suggesting that OWHTO maintains stable knee improvements and functional gains up to 10 years.

This study provides a detailed comparison of DLO and OWHTO for correcting large varus knee deformities, examining long-term functional outcomes, alignment accuracy, complication rates, and survival. Our findings indicate distinct advantages for DLO in terms of alignment precision and complication reduction, while both procedures offer comparable overall functional outcomes. Both DLO and OWHTO achieved significant improvements in KSS and KSS Function over the 5-year follow-up period. Although overall KSS scores at the 5-year mark were similar, DLO patients exhibited significantly better KSS Function scores, suggesting enhanced long-term mobility and quality of life. The superior functional improvement associated with DLO is consistent with findings in previous studies, where double-level corrections were shown to better address complex deformities through enhanced biomechanical alignment [14-16]. DLO was first introduced with the purpose of restoring a physiologic knee joint alignment in cases of severe varus knee OA with more anatomic JLO [21]. The literature shows that JLO can be significantly higher after surgery in OWHTO alone compared with DLO [22], but to our knowledge, only one study has evaluated the clinical outcomes of DLO compared with OWHTO for a short follow-up period, Abs et al. [20] have studied the clinical and radiological outcome with a mean follow-up period for all patients was 3.6 ± 1.3 years, our results are consistent with their findings of better HKA correction accuracy and less JLO in DLO group, with comparable functional outcome. Precision in HKA alignment is crucial for maintaining optimal biomechanical function, as it reduces strain on surrounding structures and potentially lowers degeneration rates over time. The frequent over-corrections observed in OWHTO further emphasize DLO’s advantage in achieving balanced alignment, as corroborated by recent biomechanical analyses showing improved HKA accuracy in DLO patients compared to OWHTO [12,14,16]. The DLO group showed significantly lower incidences of complications, particularly in JLO, PTS changes, and PFA progression. Specifically, DLO patients had a notably reduced incidence of moderate to severe JLO, consistent with other studies reporting DLO’s stability in joint alignment [20]. Minimal PTS changes were observed in DLO, with only 7.1% experiencing significant changes versus 34.4% in OWHTO, aligning with literature indicating that OWHTO carries a higher risk of slope alterations. This trend suggests that DLO’s dual-level correction approach can stabilize joint alignment and minimize stress-related degeneration, contributing to fewer long-term complications and potentially lowering revision surgery rates for DLO patients [9-12]. The 100% survival rate observed in both groups highlights the effectiveness of OWHTO and DLO in managing large varus knee deformities over their respective follow-up periods of 10 years and 5 years. However, in the OWHTO group, the identification of potential TKA candidates due to PFA progression suggests that single-level osteotomy may accelerate degenerative changes in the patellofemoral joint in large corrections even with successful alignment correction [6,7,8]. These findings align with existing literature suggesting that OWHTO, despite effectively delaying TKA, may place excessive stress on the patellofemoral compartment, contributing to early degeneration in severe varus deformities. By contrast, the DLO group, observed over a shorter follow-up period, exhibited no signs of PFA-related degeneration, which may suggest that DLO’s dual-level correction better distributes joint loads and supports patellofemoral stability. This highlights DLO’s potential as a preferable option in large deformity corrections for long-term joint preservation, particularly for younger, active patients [14-16, 20]. DLO on statistical projection to 10 years, maintain a stable 30% improvement in KSS and 25–30% in KSS Function over time, supporting consistent long-term gains. DLO is expected to achieve post-operative HKA alignment within a 2° range, enhancing biomechanical stability with a large effect size (d = 1.08). Complication Trends: DLO is projected to result in fewer PFA worsening cases over time, suggesting reduced joint degeneration risks.

Clinical implications and recommendations

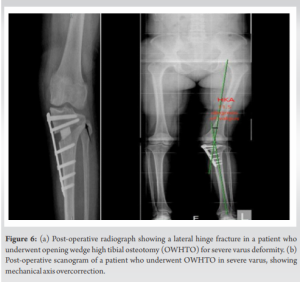

DLO’s ability to maintain joint line orientation directly translates to enhanced post-operative stability, which is particularly beneficial for active and younger patients who may place greater biomechanical stress on the knee joint. For these demographics, maintaining an optimal joint line is essential to prevent early degeneration and support higher activity levels post-surgery [12,13,14]. In addition, DLO’s improved precision in HKA alignment contributes to reduced joint degeneration risks, which supports enhanced stability and function over time, particularly in high functional demand patients [15,16]. DLO should be preferred to OWHTO as the primary technique for large varus deformities requiring correction >10°. DLO efficiently mitigates the challenges such as overcorrection, JLO, and PTS change often encountered in OWHTO, where a single-level correction may lead to uneven load distribution and increased lateral compartment strain [9-11,17, 18]. Conversely, OWHTO may be an effective choice for patients with mild to moderate deformities (<10°) [19,20]. In our study we observed OWHTO in large corrections could maintain decent function with 100% survival at 10 years, based on these results we suggest that OWHTO can be safely performed with assured long term results selectively in patients with lower functional demands like in elderly patients, where DLO might be too extensive due to suboptimal bone quality. Takeuchi et al. [5] in their study mentioned that the most effective plate position and the placement of bone substitutes into the osteotomy gap are required to guarantee the success and safety of early rehabilitation programs (Fig. 5a(i), (ii) and b).

Limitations and future research

There are several limitations to our study. This study’s retrospective design and sample size, limit generalizability. In addition, while statistical projections provided insights into DLO’s 10-year outcomes, direct long-term data would yield more definitive conclusions. Future research with larger, prospective cohorts and extended follow-up periods for DLO patients is recommended to validate these projections and confirm the observed outcome stability (Figs. 6a and b).

This study demonstrates that DLO outperforms OWHTO in correcting large varus knee deformities. DLO provides superior alignment accuracy, reduces long-term complications such as JLO, PTS changes, and PFA progression, making it the preferred choice for large deformities, particularly in younger, more active patients. While both procedures showed excellent survival rates, OWHTO may still be suitable for milder deformities or patients with lower functional demands. Overall, DLO offers a more stable, long-term solution with better functional outcomes and joint preservation. Future studies with larger cohorts and longer follow-ups are needed to further validate these findings

DLO should be preferred to OWHTO as the primary technique for large varus deformities requiring correction >10°. DLO efficiently manages the challenges such as overcorrection, JLO and PTS change often encountered in OWHTO, where a single-level correction may lead to uneven load distribution and increased lateral compartment strain. OWHTO may be an effective choice for patients with mild to moderate deformities (<10°). OWHTO can be safely performed with assured long-term results selectively in patients with lower functional demands like in elderly patients, where DLO might be too extensive due to suboptimal bone quality.

References

- 1. Amis AA. Biomechanics of high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2013;21:197-205. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Agneskirchner JD, Hurschler C, Wrann CD, Lobenhoffer P. The effects of valgus medial opening wedge high tibial osteotomy on articular cartilage pressure of the knee: A biomechanical study. Arthroscopy 2007;23:852-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Rodner CM, Adams DJ, Diaz-Doran V, Tate JP, Santangelo SA, Mazzocca AD, et al. Medial opening wedge tibial osteotomy and the sagittal plane: The effect of increasing tibial slope on tibiofemoral contact pressure. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:1431-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. El-Azab HM, Morgenstern M, Ahrens P, Schuster T, Imhoff AB, Lorenz SG. Limb alignment after open-wedge high tibial osteotomy and its effect on the clinical outcome. Orthopedics 2011;34:e622-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Takeuchi R, Woon-Hwa J, Ishikawa H, Yamaguchi Y, Osawa K, Akamatsu Y, et al. Primary stability of different plate positions and the role of bone substitute in open wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee 2017;24:1299-306. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Jung WH, Takeuchi R, Chun CW, Lee JS, Ha JH, Kim JH, et al. Second-look arthroscopic assessment of cartilage regeneration after medial opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Arthroscopy 2014;30:72-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Jung WH, Takeuchi R, Chun CW, Lee JS, Ha JH, Kim JH, et al. Efficacy of periarticular multimodal drug injection after medial opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy: A randomized, controlled study. Arthroscopy 2014;30:1261-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Lee SY, Chung CY, Lee KM, Park MS, Kwon SS. The efficacy of open-wedge high tibial osteotomy in treating varus deformities: A systematic review. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2015;97:555-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Song JH, Bin SI, Kim JM, Lee BS. What is an acceptable limit of joint-line obliquity after medial open wedge high tibial osteotomy? Analysis based on midterm results. Am J Sports Med 2020;48:3028-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Takeuchi R, Ishikawa H, Kumagai K, Yamaguchi Y, Chiba N, Akamatsu Y, et al. Fractures around the lateral cortical hinge after a medial opening-wedge high tibial osteotomy: A new classification of lateral hinge fracture. Arthroscopy 2012;28:85-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Matsui H, Koike S, Takahashi T. Hinge fracture risk and its management in OWHTO versus DLO. J Knee Surg 2022;35:44-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Babis GC, An KN, Chao EY, Rand JA, Sim FH. Double level osteotomy of the knee: A method to retain joint-line obliquity. Clinical results. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1380-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Elbardesy H, McLeod A, Ghaith HS, Hakeem S, Housden P. Outcomes of double level osteotomy for osteoarthritic knees with severe varus deformity. A systematic review. SICOT J 2022;8:7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Brown CJ, Wang Z, Allen M. Double-level osteotomy for complex varus deformities: A retrospective review of outcomes and joint line obliquity. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2020;478:1207-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kang JH, Park SE, Kim TH. Long-term outcomes of double-level osteotomy for severe varus knee deformity: Comparative study with high tibial osteotomy. J Orthop Sci 2019;24:1103-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Xu W, Shi L, Zhang X, et al . Effect of DLO and OWHTO on joint line obliquity and tibial slope: A comparative biomechanical analysis. Clin Biomech 2020;80:105187. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Smith T, Jones RM, Roberts P. Evaluating joint line obliquity in high tibial osteotomies: A comparison of single- and double-level osteotomies. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018;26:2980-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Schroter S, Nakayama H, Yoshiya S, Stockle U, Ateschrang A, Gruhn J. Development of the double level osteotomy in severe varus osteoarthritis showed good outcome by preventing oblique joint line. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2019;139:519-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Hernandez G. Double level osteotomy for correction of complex knee deformities. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol 2023 Ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Abs A, Micicoi G, Khakha R, Escudier JC, Jacquet C, Ollivier M. Clinical and radiological outcomes of double-level osteotomy versus open-wedge high tibial osteotomy for bifocal varus deformity. Orthop J Sports Med 2023;11:23259671221148458. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Nakayama H, Iseki T, Kanto R, Kambara S, Kanto M, Yoshiya S, et al. Physiologic knee joint alignment and orientation can be restored by the minimally invasive double level osteotomy for osteoarthritic knees with severe varus deformity. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2020;28:742-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Akamatsu Y, Nejima S, Tsuji M, Kobayashi H, Muramatsu S. Joint line obliquity was maintained after double-level osteotomy, but was increased after open-wedge high tibial osteotomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022;30:688-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]