Delayed presentation of lunate dislocation with acute carpal tunnel syndrome is rare. A combined dorsal-volar surgical approach ensures optimal outcomes even in delayed presentations up to 3 months without the need for any salvage procedure.

Dr. Amit Chaudhari, Department of Arthroplasty, Arthroscopy and Sports Medicine, Sportsmed, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: dramitschaudhari@gmail.com

Introduction: Lunate dislocations are uncommon high-energy wrist injuries often missed during initial evaluation in polytrauma settings.

Case Report: We present a case of a 40-year-old polytrauma patient who sustained multiple injuries following a road traffic accident. His acute injuries were predominantly treated, while a neglected isolated lunate dislocation remained undiagnosed. Three weeks later, the patient presented with acute carpal tunnel symptoms – severe wrist pain, numbness, and weakness in the distribution of the median nerve. Physical examination demonstrated tenderness over the volar wrist, reduced range of motion, and a positively elicited Phalen’s and Tinel’s sign. Radiographs and nerve conduction studies confirmed a neglected volar lunate dislocation causing compression of the carpal tunnel. Surgical intervention was performed through a combined dorsal and volar approach. Open reduction and internal fixation were followed by decompressive carpal tunnel release. Postoperatively, the patient recovered well, with resolution of symptoms and return of nearly normal wrist motion and grip strength at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion: This case underscores the importance of evaluating peripheral joints in polytrauma and shows that even delayed lunate dislocations presenting with carpal tunnel syndrome can be successfully treated using a dual approach without any salvage procedure up to 3 months.

Keywords: Lunate dislocation, neglected, polytrauma, carpal tunnel syndrome, combined approach, open reduction, internal fixation.

Lunate dislocations are uncommon, accounting for <3% of carpal dislocations, and typically arise from high-energy trauma with wrist hyperextension, ulnar deviation, and intercarpal supination [1,2]. These injuries represent the final stage (stage IV) of progressive perilunate instability described by Mayfield et al. [2]. In polytrauma patients, wrist injuries are often overlooked due to the focus on life-threatening conditions, leading to missed diagnoses in up to 25% of cases [1,3]. Delayed recognition of lunate dislocations can result in serious complications such as avascular necrosis, chronic median nerve compression, and carpal instability [3,4]. While acute presentations often include pain and functional impairment, some cases only manifest weeks later as compressive neuropathy, notably carpal tunnel syndrome [5]. Early surgical intervention is crucial, as reconstructive outcomes remain favorable if treated within 6 weeks–3 months, while further delays may necessitate salvage procedures like proximal row carpectomy or wrist arthrodesis [3,6]. This case report presents a rare instance of an isolated lunate dislocation in a polytrauma patient, initially missed, and presenting 3 weeks later with acute carpal tunnel syndrome – underscoring the need for vigilant secondary assessment in trauma cases.

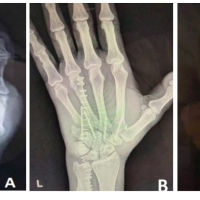

A 40-year-old male farmer by occupation presented to our hospital’s emergency department as a case of polytrauma following high velocity road traffic accident. The patient was stabilized in the emergency department as per standard ATLS protocols. During primary examination of patient in casualty patient was diagnosed with right femur shaft fracture, left proximal tibia shaft comminuted fracture, right anterior column acetabulum fracture and left 5th and 6th rib fracture Immediate treatment was directed in the standard manner as per the principles of fixation of bones. His initial radiographic investigations were predominantly directed toward his lower limbs and torso. Consequently, the wrist trauma went undiagnosed. Three weeks later, the patient presented with severe wrist pain, weakness, and numbness in his left hand for which he was referred to our Hand unit. On detailed examination, the patient had localized swelling on the palmar aspect of his left hand, and tenderness was present distal to the lister’s tubercle in line with 3rd metacarpal bone. Left wrist ROM was painful and reduced, and Phalen’s test, Tinel’s test, and Durkan test were positive which was leading toward the diagnosis of carpal tunnel syndrome. Radiographic imaging revealed classical abnormalities – a “triangular-shaped” lunate on the anterior-posterior view and a “spilled teapot” appearance on the lateral view (Fig. 1) – reflecting a volarly dislocated lunate (Mayfield stage IV) [2]. Nerve conduction studies confirmed compression of the medial nerve at the wrist.

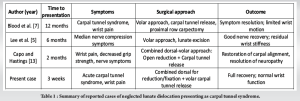

We performed open reduction and internal fixation through a dorsal approach. Dorsal capsulotomy revealed a volarly dislocated lunate, which was reduced under direct visualization and temporarily stabilized with 1.5 mm K-wires. Subsequently, a volar approach was used to perform carpal tunnel release and decompress the median nerve (Fig. 2). Under surgical loupe magnification, the median nerve was found to be intact, exhibiting only minimal hourglass constriction. The immediate post-operative radiograph demonstrated successful anatomical reduction of the lunate stabilized with 1.5 mm K-wires, maintaining its position relative to the adjacent carpal bones. Restoration of Gilula’s arcs was evident, with no signs of residual subluxation or malalignment. The scapholunate and lunotriquetral intervals appeared preserved, confirming satisfactory reduction and fixation (Fig. 3).

The wrist was immobilized in a short-arm splint for 4 weeks. The K-wires were removed at 6 weeks, followed by physiotherapy to restore wrist motion and grip strength (Fig. 4). At the 6-month follow-up, radiographs confirmed a well-reduced lunate, and the patient exhibited near-normal wrist mobility, full grip strength, resolution of numbness, and had returned to his daily activities (Fig. 5). At 1-year follow-up, radiographs demonstrated maintained reduction and lunate stability, with the patient remaining symptom-free (Fig. 6).

Lunate dislocations are rare and are often missed in the setting of polytrauma due to distracting injuries, with studies reporting initial oversight in up to 25% of cases [1,4]. Delay in diagnosis beyond 6 weeks can lead to irreversible changes such as avascular necrosis and chronic neuropathy [7,8]. The unique aspect of this case was the manifestation of acute carpal tunnel syndrome as the presenting sign of a neglected lunate dislocation—a rare occurrence. Up to 50% of acute lunate dislocations may involve median nerve compression, but such a delayed onset is seldom reported [5,9]. Radiographic clues such as the triangular lunate, disrupted Gilula’s lines, and the “spilled teapot” sign are critical for diagnosis [10] (Fig. 1). Electrophysiological testing helps confirm nerve compression. Open reduction remains the standard in subacute and chronic cases with viable lunate, as salvage procedures are better reserved for non-reconstructable injuries or those with arthritic changes [11]. A significant delay between the injury and its treatment worsens the prognosis. Trumble et al. (2001) and Harley et al. (2004) reported that reconstruction (open reduction + fixation) yields good outcomes up to about 6 weeks–3 months, but outcomes worsen significantly after that. After 3–4 months, when soft tissues become contracted and carpal alignment is fixed in malposition, reconstructive options are often not feasible, and salvage procedures such as proximal row carpectomy and wrist arthrodesis may be required in some cases [5-7,12]. In this case, the dual approach – dorsal for reduction and fixation, and volar for carpal tunnel release – allowed complete decompression and stabilization. This technique minimizes complications and enhances recovery [13]. Some advocates have described closed reduction and percutaneous pinning; however, this is less appropriate in neglected cases due to persistent scarring, ligamentous injuries, and neurovascular complications [8]. Outcome after neglected dislocation depends on the chronicity of the dislocation, associated injuries, and adequacy of reduction and stabilization [10,14]. Our patient’s result underscores the potential for recovery of wrist functionality and resolution of symptoms when an appropriate, combined surgical approach is instituted in a timely fashion, even after a delay. (Table 1).

Neglected isolated lunate dislocation presenting with acute carpal tunnel syndrome in a polytrauma patient is a challenging condition to manage and highlights the necessity for vigilant secondary surveys and a high index of suspicion. The combined dorsal and volar approach to reduce the dislocation and release the carpal tunnel can result in a successful functional outcome without the need for any salvage procedure – even if the treatment is delayed up to 3 months – provided it is managed appropriately.

Neglected lunate dislocation may manifest late with acute carpal tunnel symptoms in a polytrauma patient. A high index of suspicion, prompt recognition, and combined surgical approach can lead to successful outcomes, even when intervention is delayed.

References

- 1. Herzberg G, Comtet JJ, Linscheid RL, Amadio PC, Cooney WP, Stalder J. Perilunate dislocations and fracture-dislocations: A multicenter study. J Hand Surg Am 1993;18:768-79. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Mayfield JK, Johnson RP, Kilcoyne RK. Carpal dislocations: Pathomechanics and progressive perilunar instability. J Hand Surg Am 1980;5:226-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Cornu A, Masmejean EH. Missed lunate dislocations: Pitfalls, diagnosis and treatment. Chir Main 2016;35:309-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Al-Qattan MM, Al-Boukai AA. Missed lunate dislocation: A report of two cases with a review of the literature. Hand Surg 2001;6:111-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lee RK, Ng AW, Fung BK. Carpal tunnel syndrome secondary to chronic volar lunate dislocation. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2015;23:267-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Trumble TE, Verheyden JR, McCallister WV. Treatment of lunate and perilunate dislocations. Orthop Clin North Am 2001;32:263-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Blood TD, Fantry AJ, Morrell NT. Chronic volar lunate dislocation resulting in carpal tunnel syndrome: A case report. Case Rep Orthop 2019;2019:9809431. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Adkison JW, Chapman MW. Treatment of acute lunate and perilunate dislocations. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;164:199-207. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chan O, Stewart M. Delayed median nerve neuropathy due to unrecognised lunate dislocation. BMJ Case Rep 2013;2013:bcr2013201275. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Taleisnik J. The wrist. In: Green DP, Hotchkiss RN, Pederson WC, editors. Green’s Operative Hand Surgery. 5th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Churchill Livingstone; 2005. p. 655-716. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Meade T, Schneider LH. Proximal row carpectomy: Indications, technique, and results. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2002;10:355-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Harley BJ, Scher D, Wysocki RW, Leung A, Carlson MG. Treatment of chronic perilunate dislocations. J Hand Surg Am 2004;29:385-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Capo JT, Hastings H 2nd. Treatment of chronic lunate dislocations using combined volar-dorsal approach: A case report. Orthopedics 2006;29:715-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Inoue G, Imaeda T. Management of trans-scaphoid perilunate dislocations. Herbert screw fixation, ligamentous repair and early wrist mobilization. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 1997;116:338-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]