Orthobiologics can be used in nonunion cases, including subtrochanteric osteotomy nonunion, as a minimally invasive, safe, effective, and comparatively cheaper treatment option for fracture nonunions.

Dr. Abhijith K. Jayan, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: abhijithkjayankousthubham@gmail.com

Introduction: Hip dislocations are very common at a younger age because of predisposing factors, such as laxity of the hip. If not reduced promptly, osteonecrosis of the femoral head can occur, requiring osteotomies or hip replacement later in life. In case of severe deformities, along with hip replacement, subtrochanteric osteotomy is often needed so as to address deformity and limb length discrepancy. Non-unions at the osteotomy site are not rare and can be treated with orthobiologics. Orthobiologics have been found to increase union rates, decrease healing times, and enhance union in long bone fractures. Plateletrich plasma (PRP) and bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) are rich sources of several growth factors that promote angiogenesis and osteogenesis through multiple mechanisms.

Case Report: Here, we discuss the case of a 27-year-old male who had congenital hip dislocation, which was managed conservatively. At 18 years of age, he underwent a pelvic osteotomy and limb lengthening procedure. The symptoms subsided, but there was a recurrence of pain for the past 2 years, which was aggravated with movements. He was diagnosed with Crowe type IV dysplastic hip, and a right total hip with long stem was carried out along with subtrochanteric osteotomy. However, at 3 months of follow-up, the union was not sufficiently appreciated on radiograph, and the patient still complained of pain.

Conclusion: Hence, a single dose of BMAC injection was given, followed by three doses of PRP injections. The final follow-up was done 1 year after the surgery, and the patient had satisfactory outcomes.

Keywords: Platelet-rich plasma, orthobiologics, non-union, bone marrow aspirate concentrate, subtrochanteric osteotomy.

Hip dislocation in children can result from low-energy trauma and same-level falls, as well as high-energy trauma, such as car crashes and falls from a height, or is more commonly the result of developmental dysplasia of the hip (DDH) [1]. If neglected, the patient may develop pain, limb length discrepancy, decreased range of movement, and avascular necrosis of the femoral head. However, pelvic support osteotomy with femoral lengthening can be done in patients with neglected cases of pediatric hip dislocation [2]. Patients with high congenital hip dislocation may benefit from total hip arthroplasty (THA). They may need femoral shortening osteotomy, distal advancement of the greater trochanter, and cup placement at the level of the real acetabulum [3]. Because of the changed architecture brought on by the proximal femur’s angulation in both the frontal and sagittal planes, total hip replacement following pelvic support osteotomy can be difficult [4]. For the prosthetic stem to be successfully implanted during THA in patients with proximal femoral deformity, osteotomy at the deformity site is frequently necessary [5,6]. With a typical trochanteric osteotomy, it may be challenging to ensure enough exposure of the acetabulum and femur, during primary or revision hip arthroplasty following pelvic osteotomy. In order to help address these challenging concerns in revision THA, an extended trochanteric osteotomy may also be needed [7-9]. However, there are instances of non-union at the osteotomy site that often need further interventions. In case of non-union, orthobiologics are a novel and effective option of treatment [10]. Bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) and platelet-rich plasma (PRP) have been studied to be effective for non-union of fractures of long bones, promoting union and improving functional outcome [10-12]. In this case report, we discuss a patient with a neglected dysplastic hip for whom PRP and BMAC were administered to improve healing, following signs of osteotomy site non-union following THA.

A 27-year-old male presented to our outpatient department with right hip pain for 2 years. The patient had an alleged history of right hip dislocation at 9 months of age, which was treated with conservative management at a local hospital. However, allegedly, no reduction could be done, and the patient was asked to wait till skeletal maturity for surgical correction through osteotomy. At 12 years of age, the patient developed complaints of difficulty in sitting cross-legged, which further progressed to difficulty in cycling and walking for longer distances at 14 years of age. After 2 years, the patient underwent pelvic stabilization osteotomy at an outside center. The patient also underwent limb lengthening procedures using the limb reconstruction system to address the limb length discrepancy. However, even after the surgery, the patient had difficulty walking and limping due to limb length discrepancy. The patient now presented with severe pain and limping in the right hip.

On examination, previous scar marks were visible over the hip and thigh, tenderness was present over the anterior joint line, and joint movements were restricted compared to the contralateral hip. Shortening of four cm was present over the right lower limb (Fig. 1). Radiograph of pelvis anteroposterior view revealed right dysplastic hip (Crowe’s type IV) with deformity over the shaft of the femur. Overriding of the greater trochanter and destruction of the femur head were noticed (Fig. 2). Further investigations were done, including computed tomography of the pelvis with bilateral hip and right femur for surgical planning. The patient was planned for subtrochanteric osteotomy plus THA.

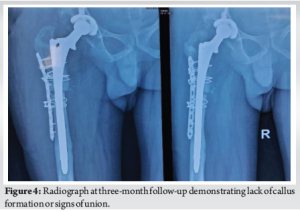

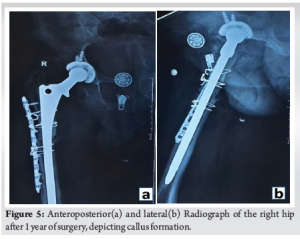

With the patient in left lateral decubitus position, the hip joint was exposed through a direct lateral approach extended distally (Hardinge technique). The incision was started at 5 cm proximal to the greater trochanter and extended distally to 10 cm below the greater tuberosity. Serial acetabular reaming was done, followed by cementless acetabular cup placement and fixation using two acetabular screws. Serial femoral broaching was done, and a long stem was used for the femur. Reduction was difficult due to the proximal migration of the greater trochanter. Hence, to aid the reduction, a subtrochanteric osteotomy was performed. The femur was exposed laterally, and subtrochanteric osteotomy was done using an osteotome and oscillating saw at the site of maximum deformity. Osteotomy site was fixed using a ten-hole locking compression plate laterally, fixed proximally and distally to the osteotomy site using 18G Stainless Steel wire, and a long stem femoral implant (solution stem) was used. Intramedullary fit was assessed using fluoroscopy. Range of movement and stability of the implant were assessed before closure. Post-operative radiograph showed signs of a well-positioned implant (Fig. 3). Post-operatively, range of movement and strengthening exercises were started the next day. The patient was started on painkillers. Low molecular weight heparin was administered for 7 days, and Apixaban 2.5 mg twice daily was continued for 3 months to prevent deep vein thrombosis. The patient was mobilized after three months of surgery. However, it was ensured that the range of movement and strengthening exercises were carried out. Initially, the patient was advised to perform hip abductor and core strengthening exercises. The patient was first followed up at 14 days of surgery for stitch removal, and then followed up at each month. Serial radiographs were done, and the wound condition, movement, and functions of the joint were assessed at each follow-up. At 3 months of follow-up, the patient still complained of pain in the right thigh and difficulty in movement. Furthermore, there were no radiological signs of healing (Fig. 4 for Radiograph). Hence patient was administered injections of orthobiologics to improve healing. The patient was given a BMAC injection at three months after the surgery, as the osteotomy was suspected to progress to non-union. The patient also received three doses of PRP injection at 4 months after surgery, 8 months post-operatively, and 10 months after surgery. All injections were given in a minor theatre, under all aseptic precautions with autologous preparation of BMAC and PRP. BMAC was prepared after aspiration of bone marrow and after centrifugation in the centrifuge machine. BMAC was injected into the fracture site. PRP was prepared after the collection of 30 mL of blood from the antecubital vein. Centrifugation was done, and the PRP prepared was activated with the activator, and the PRP was injected into the fracture site. The patient was then followed up at 1 year from the date of surgery. The patient has significantly improved results and was able to carry out daily activities. Radiograph also showed significant improvement in terms of callus formation (Fig. 5).

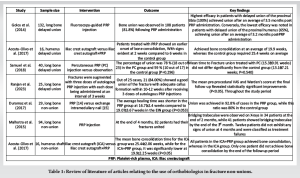

Dysplastic hip is a major cause of pediatric hip dislocations apart from traumatic causes [13]. Neglected dislocations result in avascular necrosis of the hip. Interference with the extraosseous blood flow during the injury appears to cause necrosis [14]. Regardless of the child’s age, surgically treating a high developmental hip dislocation is technically challenging and carries a significant risk of stiffness in the hips and femoral head necrosis. The majority of researchers believe that treating children with DDH who are older than 3-years-old surgically is challenging and fraught with difficulties. Femoral lengthening, pelvic osteotomy, and open reduction are the suggested techniques [15]. Hip osteotomies aim to realign biological structures to enhance gait mechanics. Pelvic support osteotomy, which supports the pelvis on the upper end of an osteotomized femur, was developed to address issues related to hip instability. Pelvic osteotomy is often combined with procedures for femur lengthening to address the limb length discrepancy. Limb lengthening can be done with either monolateral frame devices or the Ilizarov frame. However, even after pelvic osteotomies, a patient may develop osteonecrosis of the femur head. In a few cases, even after pelvic osteotomies, there will be persistent hip dysplasia. In such cases, total hip replacement, though necessary, can be difficult due to the change in pelvic orientation as a result of osteotomy [3,4]. In such patients, hip arthroplasty has a high prevalence of complications, such as aseptic loosening, early post-operative dislocation, late infection, and peroneal and femoral nerve palsy. They may also need longer operating times and may need trochanteric osteotomies. A modular prosthesis has been utilized for femoral repair and fixation during THA, and osteotomy has been carried out at the most severely damaged femur sites for subtrochanteric proximal femoral deformity. Cementless THA with distal advancement of the greater trochanter, femoral shortening osteotomy, and soft-tissue releases might significantly lessen discomfort and enhance hip function. The cup needs to be situated close to the anatomic level or even lower to produce strong abduction strength and reliable fixation of the acetabular component [3]. To lower the femoral head, the femur must be somewhat shortened. The modular prosthesis comprises a cylindrical, polished femoral stem and a porous-coated proximal component. More efficient proximal femoral fixation is made possible by the press-fit fixation between the proximal component and the elliptical part of the proximal femur [5]. Non-union of the osteotomy, migration or fracture or both of the osteotomy fragment, wire breakage, trochanteric bursitis necessitating wire removal, and prolonged hip abductor weakness are among the documented side effects of routine trochanteric osteotomy [8]. Non-union can be treated with several surgical and non-surgical options. Orthobiologics are a novel non-surgical treatment option in patients with long bone non-union. Orthobiologics have been found to increase union rates, decrease healing times, and enhance union in long bone fractures. PRP is a rich source of several growth factors, which are essential for tissue repair. These include platelet-derived growth factor, transforming growth factor-beta, and vascular endothelial growth factor. These factors promote angiogenesis and osteogenesis [16]. BMAC contains Mesenchymal stem cells and growth factors. Due to their Osteogenic and Osteo-induction properties, they are nowadays utilized to accelerate bone healing in cases of Non-union and Delayed union [17]. In comparison with traditional methods, such as Autologous iliac crest bone grafting, PRP and BMAC have the benefit of being minimally invasive procedures with fewer complications. Golos et al., in a prospective study in 132 cases of long bone delayed union, after Fluoroscopy-guided PRP injection into the fracture, bone union was reported in 81.8% after a mean duration of 3.5 months [18]. Carlos Acosta et al., conducted a randomized controlled trial in humerus delayed union cases; they observed early fracture consolidation in patients who received PRP along with Autologous iliac crest bone graft (19.9 weeks) when compared to bone graft alone (25.4 weeks) [19]. Ranjan et al., in their case series of 25 patients with long bone delayed union, three doses of PRP at a week interval were administered into the fracture site, solid union was noticed in 84% of cases after 10–12 weeks [20]. Duramaz et al. in their case–control study observed that the average healing time was shorter in the PRP group compared to the exchange nailing group in long bone non-union [21]. Malhotra et al., gave PRP injection under an image intensifier to 95 patients with long bone non-union and reported union in 82 patients at the end of 4 months [22]. Table 1 is a detailed table with a comprehensive review of the use of ortho-biologics for the treatment of fracture non-unions.

Previous studies have shown that PRP and BMAC are cost-effective options for delayed union and non-union cases without significant complications. Contraindications for this procedure include active infection, bleeding disorders, malignancy, and hemodynamic instability. Neglected dysplastic hips require total hip replacement in adulthood, and many cases with deformity may need osteotomies. Orthobiologics are a viable treatment option in these cases and are minimally invasive, with excellent outcomes.

This is a rare case of neglected hip dislocation with a history of failure of pelvic stabilization osteotomy and lengthening procedures, which was managed with THA and subtrochanteric osteotomy. From this experience, we came to the conclusion that similar to other fracture non-unions; orthobiologics can be used in osteotomy site non-unions and are highly effective.

Orthobiologics can be used in non-union cases, including subtrochanteric osteotomy non-union. While traditional treatment options for non-union (like bone grafting) are more invasive, orthobiologics provide a minimally invasive, safe, and comparatively cheaper treatment option for fracture non-unions.

References

- 1.Haram O, Odagiu E, Florea C, Tevanov I, Carp M, Ulici A. Traumatic hip dislocation associated with proximal femoral physeal fractures in children: A systematic review. Children (Basel) 2022;9:612. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Gursu S, Demir B, Yildirim T, Turgay E, Bursali A, Sahin V. An effective treatment for hip instabilities: Pelvic support osteotomy and femoral lengthening. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2011;45:437-45. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Eskelinen A, Helenius I, Remes V, Ylinen P, Tallroth K, Paavilainen T. Cementless total hip arthroplasty in patients with high congenital hip dislocation. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:80-91. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Thabet AM, Catagni MA, Guerreschi F. Total hip replacement fifteen years after pelvic support osteotomy (PSO): A case report and review of the literature. Musculoskelet Surg 2012;96:141-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Deng X, Liu J, Qu T, Li X, Zhen P, Gao Q, et al. Total hip arthroplasty with femoral osteotomy and modular prosthesis for proximal femoral deformity. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:282. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Onaga M, Nakasone S, Ishihara M, Igei T, Washizaki F, Kuniyoshi S, et al. Total hip arthroplasty after failed transtrochanteric rotational osteotomy for osteonecrosis of the femoral head: Analysis of three-dimensional morphological features. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2024;25:194. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Miner TM, Momberger NG, Chong D, Paprosky WL. The extended trochanteric osteotomy in revision hip arthroplasty: A critical review of 166 cases at mean 3-year, 9-month follow-up. J Arthroplasty 2001;16:188-94. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Sundaram K, Siddiqi A, Kamath AF, Higuera-Rueda CA. Trochanteric osteotomy in revision total hip arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2020;5:477-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.MacDonald SJ, Cole C, Guerin J, Rorabeck CH, Bourne RB, McCalden RW. Extended trochanteric osteotomy via the direct lateral approach in revision hip arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;417:210-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Impieri L Pezzi A, Hadad H, Peretti GM, Mangiavini L, Rossi N. Orthobiologics in delayed union and non-union of adult long bones fractures: A systematic review. Bone Rep 2024;21:101760. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Andersen C, Wragg NM, Shariatzadeh M, Wilson SL. The use of platelet-rich plasma (PRP) for the management of non-union fractures. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2021;19:1-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Van Vugt TA, Geurts JA, Blokhuis TJ. Treatment of infected tibial non-unions using a BMAC and S53P4 BAG combination for reconstruction of segmental bone defects: A clinical case series. Injury 2021;52:S67-71. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Ciftdemir M, Aydin D, Ozcan M, Copuroglu C. Traumatic posterior hip dislocation and ipsilateral distal femoral fracture in a 22-month-old child: A case report. J Pediatr Orthop B 2014;23:544-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Barquet A. Traumatic hip dislocation in childhood. A report of 26 cases and review of the literature. Acta Orthop Scand 1979;50:549-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Wojciechowski P, Kusz DJ, Cieliński LS, Dudko S, Bereza PL. Neglected, developmental hip dislocation treated with external iliofemoral distraction, open reduction, and pelvic osteotomy. J Pediatr Orthop B 2012;21:209-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Foster TE, Puskas BL, Mandelbaum BR, Gerhardt MB, Rodeo SA. Platelet-rich plasma: From basic science to clinical applications. Am J Sports Med 2009;37:2259-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Canton G, Tomic M, Tosolini L, Di Lenarda L, Murena L. Use of bone marrow aspirate concentrate (BMAC) in the treatment of delayed unions and nonunions: A single-center case series. Acta Biomed 2023;94:e2023118. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Gołos J, Waliński T, Piekarczyk P, Kwiatkowski K. Results of the use of platelet rich plasma in the treatment of delayed union of long bones. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2014;16:397-406. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Acosta-Olivo C, Garza-Borjon A, Simental-Mendia M, Vilchez-Cavazos F, Tamez-Mata Y, Peña-Martinez V. Delayed union of humeral shaft fractures: Comparison of autograft with and without platelet-rich plasma treatment: A randomized, single blinded clinical trial. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2017;137:1247-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Ranjan R, Kumar R, Jeyaraman M, Arora A, Kumar S, Nallakumarasamy A. Autologous platelet-rich plasma in the delayed union of long bone fractures - A quasi experimental study. J Orthop 2023;36:76-81. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Duramaz A, Ursavaş HT, Bilgili MG, Bayrak A, Bayram B, Avkan MC. Platelet-rich plasma versus exchange intramedullary nailing in treatment of long bone oligotrophic nonunions. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2018;28:131-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Malhotra R, Kumar V, Garg B, Singh R, Jain V, Coshic P, et al. Role of autologous platelet-rich plasma in treatment of long-bone nonunions: A prospective study. Musculoskelet Surg 2015;99:243-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]