Geriatric tibial plafond fractures have a high complication rate and tibiotalar nailing provides a means to decrease these complications while expediting weight-bearing status.

Dr. Porter Young, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery and Rehabilitation, University of Florida-Jacksonville, 655 West 8th Street Jacksonville - 32209, Florida, United States. E-mail: porter.young@jax.ufl.edu

Introduction: Tibial pilon fractures present a complex challenge, particularly in geriatric patients with comorbidities and compromised soft tissue. Traditional treatment options such as open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF) and tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) nailing have shown variable outcomes, often complicated by infection, nonunion, and malunion. Tibiotalar nailing is an alternative approach that preserves subtalar joint motion while providing stable fixation, though, there is limited literature on its efficacy in geriatric pilon fractures. This report describes a case of a 64-year-old female with multiple comorbidities presenting with tibial pilon fracture successfully managed with antegrade tibiotalar intramedullary nailing, highlighting the potential advantages of this technique.

Case Report: A 64-year-old female with a history of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, hypertension, and a significant smoking history presented with a right tibial pilon and distal fibula fracture following a fall down the stairs. Due to her medical comorbidities and poor soft tissue envelope, she was at high risk for complications with ORIF. After discussing multiple treatment options, she elected to proceed with a tibiotalar intramedullary nail to optimize function while minimizing surgical morbidity. The procedure was performed using a suprapatellar approach, and an 8mm nail was inserted to preserve bone stock and future surgical options. Postoperatively, she progressed well, achieving full fracture healing by 9 months with minimal pain and functional independence. She declined further surgical intervention for hardware removal or ankle fusion, reporting satisfaction with her outcome.

Conclusion: This case highlights the successful use of tibiotalar nailing as a viable alternative to ORIF and TTC nailing for managing geriatric pilon fractures with significant comorbidities. By preserving subtalar joint function, this approach offers potential advantages in mobility and quality of life while mitigating the risks associated with more invasive procedures. Given the limited existing literature on this technique, this report contributes to the growing body of evidence supporting its use. Further studies are warranted to compare tibiotalar nailing with conventional approaches in larger cohorts to refine its indications and optimize patient outcomes.

Keywords: Tibial plafond fractures, tibiotalar intramedullary nailing, geriatric trauma.

Tibial pilon fractures often occur after high-energy trauma and comprise about 5–10% of all tibial fractures with an overall low incidence [1-4]. Multiple treatment modalities are available with the overall goal being restoration of limb function while minimizing complications. Minimally displaced fractures may be treated with casting and non-weight bearing [4-6]. External fixation may be used for temporary initial stabilization in unstable fractures and as part of a staged approach with subsequent open reduction and internal fixation (ORIF), which is the most common treatment [7-9]. ORIF is considered the gold standard treatment for pilon fractures and allows for adequate alignment and healing but an increased risk for soft tissue complications. Intramedullary nailing using an antegrade tibiotalar or tibiotalocalcaneal (TTC) nail is an alternative technique that is considered in patients with extensive comminution, poor bone quality, and significant soft tissue compromise. In more severe comminuted fractures, primary arthrodesis is utilized for salvage [7,10]. Secondary arthrodesis may be performed after a failed ORIF with extensive complications. Amputation is often a last resort treatment for compromising and non-reconstructable fractures with low limb viability [10]. Pilon fractures are associated with notable complication rates after repair including wound complications such as necrosis and dehiscence (2–10%), superficial and deep infection (2–9%), malunion (2–5%), nonunion (2–10%), need for revision (5–22%), and hardware removal (10–40%) [4,11-15]. When initial treatment for pilon fracture fails, arthrodesis may be used to repair which occurs in about 5.3% of patients [16]. In severe cases where limb salvage is not possible, amputation may be required which occurs in about 2.9% of cases [16]. Smoking is influential factor which has been shown to affect outcomes after pilon fracture repair. Age over 40 and tobacco have both been shown to be independent predictors of secondary arthrodesis [16]. For general ankle fractures, heavy smokers have been shown to exhibit delayed union, extended postoperative pain duration, swelling at fracture, and superficial and deep wound infections with overall delayed wound healing [17]. Smoking has also been associated with poorer post-surgical ankle function and health-related quality of life after repair of pilon fracture [18]. In this report, we describe the case of a 64-year-old female with right tibial pilon fracture treated with antegrade tibiotalar intramedullary nailing. After a detailed discussion with the patient about her treatment options, our patient ultimately decided to proceed with a tibiotalar nail in order to preserve ankle and subtalar joint function, but not endure the significant soft tissue risks associated with open reduction internal fixation. This case report will review the current literature on tibiotalar nailing for geriatric tibial plafond fractures and highlight the benefits and drawbacks of the technique.

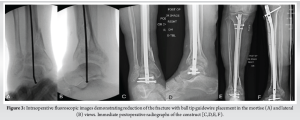

Our case involves a 64-year-old female with a past medical history significant for chronic obstructive pulmonary disease on two liters of home oxygen, hypertension and one pack per day smoking history who presented to the emergency department after a trip and fall down stairs where she sustained a right tibial plafond and distal fibula fracture (Fig. 1). There was moderate swelling about the ankle, skin was intact and she was neurovascularly intact. She underwent temporary stabilization in an external fixator to allow for soft tissue rest and a postoperative computed tomography scan was obtained to further characterize her injury. This demonstrated an impacted, comminuted tibial plafond and distal fibula fracture with osteopenic bone quality (Fig. 2).

Multiple treatment options were discussed with the patient, including nonoperative treatment with conversion to a cast, open reduction internal fixation (ORIF), TTC nailing, or tibiotalar nailing with or without formal fusion. The patient wished to optimize her function as much as possible and was ambulatory without assistive devices prior to this fall. However, her thin soft tissue envelope and multiple medical problems put her at high risk for complications with ORIF. She did not want to fuse her entire hindfoot so she ultimately decided to proceed with a tibiotalar nail.

The tibiotalar nail was performed in the supine position on a radiolucent bed. The suprapatellar approach for tibial nailing was utilized. The fracture was closed reduced with manual manipulation and traction, ensuring to keep the talus centered below the tibia on a mortise and lateral fluoroscopic views. The ankle joint was maintained in neutral dorsiflexion and 5° of external rotation and valgus. The guidewire was then inserted down into the talus, and the canal was sequentially reamed. Of note, the patient had very osteopenic bone quality allowing for direct impaction of the ball-tipped guide wire into the talus. A threaded guidewire can be introduced in a retrograde manner through the calcaneus and into the talus for cases with more dense talar bone stock. We chose to utilize an 8 mm nail in order to preserve bone stock if a hindfoot nail was needed in the future. The ankle joint was not prepped for a fusion to preserve motion if the patient wished to have the nail removed in the future, once the fracture healed. Two interlocking screws were placed distally and three placed proximally (Fig. 3). She was placed into a posterior slab splint and made non-weight bearing for 6 weeks.

At the 2-week postoperative visit, her incisions were well healed, and her pain was improving. At the 6-week visit, her pain was continuing to improve, and she progressed to weight bearing as tolerated with physical therapy. At the most recent visit, 9 months after the procedure, she rated her pain as 2 out of 10 and was only utilizing muscle relaxers intermittently for pain control. On physical exam, she had well-healed incisions with no signs of infection and was ambulating with a cane. Radiographs demonstrated complete healing of the fractures and a maintained ankle joint. We discussed hardware removal with or without a formal ankle fusion to help improve pain, but she did not feel her current pain warranted further surgical intervention and was happy with her current function (Fig. 4). She will follow up on an annual basis for monitoring. The patient gave verbal consent for her case to be presented in this report.

ORIF and TTC nailing are two of the most common procedures performed for geriatric tibial plafond fractures. Geriatric patients have a higher rate of complications after these fractures due to their quality of the bone, soft tissue status, and blood circulation. These injuries tend to have impaction, which decreases talar stability and contributes to failure with fixation. In addition, geriatric patients are not as tolerant of non-weight-bearing [19]. These factors combined make TTC, which can be performed minimally invasive with minimal tissue injury in the context of more unstable fractures, a favorable option [19]. Haller et al. examined pilon fractures in patients over 60 treated with ORIF and found a treatment failure rate of 43%, infection rate of 10%, and a malunion rate of 3% [20]. This study did not show a significant difference between these rates in patients over and under 60. White et al. examined ORIF after pilon fracture in patients of a wide age range and found a deep wound infection and dehiscence rate of 6.3% [21]. In addition, a systematic review by Daniels et al. using 355 patients with pilon fractures treated with ORIF found the complication rates for superficial infection (2.8%), deep infection (13.8%), osteoarthritis (3.7%), nonunion (0.85%), malunion (0.56%), delayed union (3.1%), bone grafting (2.3%), and amputation (1.1%) [22]. Data on complications after TTC nailing for pilon fractures and comparison with ORIF is more limited due to lower number of available studies. Georgiannos et al. compared ORIF and TTC nailing in geriatric unstable ankle fractures, shorter hospital stay, and similar ankle scores in both groups [23]. In a similar study, Balziano et al. found a 50% complication rate with ORIF and 22.2% rate with TTC nailing with 28.6% and 11.1% revision rates respectively and higher ankle scores after ORIF [24]. Ebaugh et al., Schray et al., and a systematic review by Cinats et al. found a surgical complication rate of 16–20% after TTC nailing and meta-analysis conducted by Lu et al. found a pooled complication rate of 28% [25-28]. Another surgical technique for the treatment of geriatric pilon fracture is tibiotalar nailing, which was performed in our case and has been documented in several studies. Mückley et al. described a technique for tibiotalar antegrade nailing for posttraumatic and osteoarthritis in 110 patients and demonstrated a 90% rate of success with a 5.5% reoperation rate and 4.5% nonunion rate [29]. There were also a recorded 3 superficial infections, 8 deep infections, and 3 subtalar osteoarthritis incidences in this study. Subtalar osteoarthritis was associated with poor bone quality. 70 patients had improvement in symptoms while 37 had no change in symptoms and three had worsening symptoms. Hasan et al. identified 15 patients who underwent antegrade tibiotalar nailing which included six open pilon fractures. Two patients (13.3%) experienced superficial infection and one (6.7%) had a failed fusion with a broken distal locking screw, with the remaining patients having pain-free restored ambulation after at least 12 months. Niikura et al. described two younger patients with anterograde tibiotalar intramedullary nailing for pilon fracture [30]. Notably, the subtalar joints had a preserved range of motion. In another study, Guryel et al. analyzed tibial pilon fracture patients who included 26 treated with ORIF and 6 treated with tibiotalar antegrade nailing. The ORIF group had complications of deep infection (12%), nonunion (8%), malunion (4%), posttraumatic osteoarthritis (27%), and the secondary conversion to ankle replacement or fusion (12%), whereas the tibiotalar nailing group had no complications, shorter hospital stay, faster return to work, and higher ankle scores [31]. Both tibiotalar and TTC nailing have been utilized in pilon fractures with poor soft tissue or bone quality, severe comminution and bone loss, post-traumatic arthritis, or failed other intervention. Both techniques have been associated with early weight bearing and lower rates of complications compared to ORIF, which varies by study. They are also less invasive than ORIF and avoid extensive soft tissue dissection, reducing the risk of infection and wound complications, especially in cases of poor soft tissue integrity. The tibiotalar intramedullary nail provides an alternative to the TTC nail, which preserves the subtalar joint, allowing for better preservation of motion and ankle biomechanics for better hindfoot mobility. It is thought that this motion preservation may maintain the joints ability to adapt to force, allowing for protection against impact loading [32]. The downside of tibiotalar compared to TTC nailing is that a lack of engagement of the calcaneus may yield an overall weaker fixation and greater chance for misalignment with more severe fractures. However, the tibiotalar nail spans the entire tibia which greatly decreases the chances of peri-implant fracture that can occur just proximal to a TTC nail. Another potential downside is that antegrade insertion of the nail requires an approach through the knee, which is not typically injured. In patients with poor bone stock, the risk of subtalar osteoarthritis must be weighed against the potential benefit of increased construct stability when using a tibiotalar nail. Another benefit of the tibiotalar nail is that surgeons with limited experience with TTC nailing are likely to be more comfortable with tibiotalar nailing and it still reserves the option for hindfoot nailing if the tibiotalar nail needs to be revised. In essence, the tibiotalar nail can act as an internal external fixator and substantially decrease the complications associated with primary ORIF and TTC nailing.

This case highlights the successful use of tibiotalar nailing as a viable alternative for the management of geriatric pilon fractures with significant comorbidities and compromised soft tissue. The decision to proceed with a tibiotalar nail allowed for fracture stabilization while preserving subtalar motion, ultimately leading to a satisfactory functional outcome and pain relief in our patient. Given the challenges associated with pilon fractures in elderly patients, including poor bone stock, high rates of nonunion, and increased complications following ORIF, this case adds to the growing body of evidence supporting intramedullary fixation as a reasonable alternative. While TTC nailing may provide greater stability, it sacrifices subtalar motion, which can be critical for long-term mobility and patient satisfaction. Tibiotalar nailing, in contrast, offers a middle ground by allowing for early weight-bearing with joint preservation. This study contributes to the evolving surgical decision-making process for complex pilon fractures, particularly in high-risk patients where standard ORIF poses significant complications. Given the limited availability of studies examining tibiotalar nailing for geriatric pilon fractures, further studies are warranted to explore the technique further and compare it with TTC nailing in larger cohorts, which will be valuable in refining indications and optimizing treatment strategies.

Geriatric tibial plafond fractures have a high complication rate, and tibiotalar nailing provides a means to decrease these complications while expediting weight-bearing status.

References

- 1. Chen H, Cui X, Ma B, Rui Y, Li H. Staged procedure protocol based on the four-column concept in the treatment of AO/OTA type 43-C3.3 pilon fractures. J Int Med Res 2019;47:2045-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Mauffrey C, Vasario G, Battiston B, Lewis C, Beazley J, Seligson D. Tibial pilon Fractures: A review of incidence, diagnosis, treatment, and complications. Acta Orthop Belg 2011;77:432-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Luo TD, Eady JM, Aneja A, Miller AN. Classifications in brief: Rüedi-allgöwer classification of tibial plafond fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2017;475:1923-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Mair O, Pflüger P, Hoffeld K, Braun KF, Kirchhoff C, Biberthaler P, et al. Management of pilon fractures-current concepts. Front Surg 2021;8:764232. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Othman M, Strzelczyk P. Results of conservative treatment of “pilon” fractures. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2003;5:787-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Resch H, Pechlaner S, Benedetto KP. Long-term results after conservative and surgical treatment of fractures of the distal end of the tibia. Aktuelle Traumatol 1986;16:117-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Krettek C, Bachmann S. Pilon fractures. Part 1: Diagnostics, treatment strategies and approaches. Chirurg 2015;86:87-101;quiz 102-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Grose A, Gardner MJ, Hettrich C, Fishman F, Lorich DG, Asprinio DE, et al. Open reduction and internal fixation of tibial pilon fractures using a lateral approach. J Orthop Trauma 2007;21:530-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Tornetta P 3rd, Weiner L, Bergman M, Watnik N, Steuer J, Kelley M, et al. Pilon fractures: Treatment with combined internal and external fixation. J Orthop Trauma 1993;7:489-96. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Beaman DN, Gellman R. Fracture reduction and primary ankle arthrodesis: A reliable approach for severely comminuted tibial pilon fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2014;472:3823-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Carbonell-Escobar R, Rubio-Suarez JC, Ibarzabal-Gil A, Rodriguez-Merchan EC. Analysis of the variables affecting outcome in fractures of the tibial pilon treated by open reduction and internal fixation. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2017;8:332-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Harris AM, Patterson BM, Sontich JK, Vallier HA. Results and outcomes after operative treatment of high-energy tibial plafond fractures. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27:256-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Sirkin M, Sanders R, DiPasquale T, Herscovici D Jr. A staged protocol for soft tissue management in the treatment of complex pilon fractures. J Orthop Trauma 1999;13:78-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Van Den Berg J, Monteban P, Roobroeck M, Smeets B, Nijs S, Hoekstra H. Functional outcome and general health status after treatment of AO type 43 distal tibial fractures. Injury 2016;47:1519-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. McCann PA, Jackson M, Mitchell ST, Atkins RM. Complications of definitive open reduction and internal fixation of pilon fractures of the distal tibia. Int Orthop 2011;35:413-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Massey LE, Oladeji LO, Esposito ER, Cook JL, Della RG, Crist BD. Incidence and risk factors of ankle fusion after pilon fracture: A retrospective review. Curr Orthop Pract 2023;34:34-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Jerjes W, Ramsay D, Stevenson H, Yousif A. Effect of chronic heavy tobacco smoking on ankle fracture healing. Foot Ankle Surg 2024;30:343-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Van Der Vliet QM, Ochen Y, McTague MF, Weaver MJ, Hietbrink F, Houwert RM, et al. Long-term outcomes after operative treatment for tibial pilon fractures. OTA Int 2019;2:e043. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Ryan G, Birk M, Buckley R. What is the best surgical treatment for the geriatric patient with a severe ankle or pilon fracture – TTC nail or ORIF? Injury 2024;55:111978. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Haller JM, Githens M, Rothberg D, Higgins T, Nork S, Barei D. Pilon fractures in patients older than 60 years of age: Should we be fixing these? J Orthop Trauma 2020;34:121-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. White TO, Guy P, Cooke CJ, Kennedy SA, Droll KP, Blachut PA, et al. The results of early primary open reduction and internal fixation for treatment of OTA 43.C-type tibial pilon fractures: A cohort study. J Orthop Trauma 2010;24:757-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Daniels NF, Lim JA, Thahir A, Krkovic M. Open pilon fracture postoperative outcomes with definitive surgical management options: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2021;9:272-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Georgiannos D, Lampridis V, Bisbinas I. Fragility fractures of the ankle in the elderly: Open reduction and internal fixation versus tibio-talo-calcaneal nailing: Short-term results of a prospective randomized-controlled study. Injury 2017;48:519-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Balziano S, Baran I, Prat D. Hindfoot nailing without joint preparation for ankle fractures in extremely elderly patients: Comparison of clinical and patient-reported outcomes with standard ORIF. Foot Ankle Surg 2023;29:588-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Lu V, Tennyson M, Zhou A, Patel R, Fortune MD, Thahir A, et al. Retrograde tibiotalocalcaneal nailing for the treatment of acute ankle fractures in the elderly: A systematic review and meta-analysis. EFORT Open Rev 2022;7:628-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Ebaugh MP, Umbel B, Goss D, Taylor BC. Outcomes of primary tibiotalocalcaneal nailing for complicated diabetic ankle fractures. Foot Ankle Int 2019;40:1382-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Schray D, Ehrnthaller C, Pfeufer D, Mehaffey S, Böcker W, Neuerburg C, et al. Outcome after surgical treatment of fragility ankle fractures in a certified orthogeriatric trauma center. Injury 2018;49:1451-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Cinats DJ, Kooner S, Johal H. Acute hindfoot nailing for ankle fractures: A systematic review of indications and outcomes. J Orthop Trauma 2021;35:584-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Mückley T, Hofmann G, Bühren V. Tibiotalar arthrodesis with the tibial compression nail. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2007;33:202-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Niikura T, Miwa M, Sakai Y, Lee SY, Oe K, Iwakura T, et al. Ankle arthrodesis using antegrade intramedullary nail for salvage of nonreconstructable tibial pilon fractures. Orthopedics 2009;32(8):611–614 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Guryel E, Lee C, Barakat A, Robertson A, Freeman R. Primary ankle fusion using an antegrade nail into the talus for early treatment of OTA type C3 distal tibial plafond fractures: A preliminary report. Foot Ankle Int 2024;45:208-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Hasan YO, Bourget-Murray J, Page P, Penn-Barwell JG, Handley R. Tibiotalar nailing using an antegrade intramedullary tibial nail: A salvage procedure for unstable distal tibia and ankle fractures in the frail elderly patient. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2024;34:847-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]