This experience illuminates the importance of keeping a less common diagnosis as a differential, particularly in cystic-lytic areas after hip arthroplasty. The long-standing lytic lesion around the implant may mimic benign conditions, such as LCH, especially in patients who underwent multiple surgeries in the past. Histopathology and immuno-phenotyping play a vital role in the confirmation of a diagnosis.

Dr. Mukund Madhav Ojha, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Nagpur, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: mukund1203@gmail.com

Introduction: Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease primarily affecting children. The occurrence of osseous LCH is rare in adults. The lytic lesion of LCH can resemble the lytic lesion of septic or aseptic loosening in an operated case of arthroplasty.

Case Report: We report an operated case of total hip arthroplasty whose peri-prosthetic lesion was uncertain by clinical and radiological investigations. Later, a core biopsy revealed the unexpected diagnosis of LCH.

Conclusion: LCH is an infrequent phenomenon in an adult. This experience taught us the importance of core biopsy and phenotyping in patients with doubtful cystic-lytic lesions over the adjacent bone to the prosthesis.

Keywords: Langerhans cell histiocytosis, total hip arthroplasty, osteomyelitis.

Langerhans cell histiocytosis (LCH) is a rare disease primarily seen in children, with a reported incidence in adults of 1–2 cases/million annually [1,2]. Adult disease is typically solitary and is often observed in the axial skeleton, particularly in the skull, ribs, vertebrae, or mandibles. In comparison, long bones, such as the femur and humerus, are less frequently involved in both children and adults [3]. We report an operated case of total hip arthroplasty (THA) whose peri-prosthetic lesion was uncertain by clinical and radiological investigations. Later, a core biopsy revealed the unexpected diagnosis of LCH.

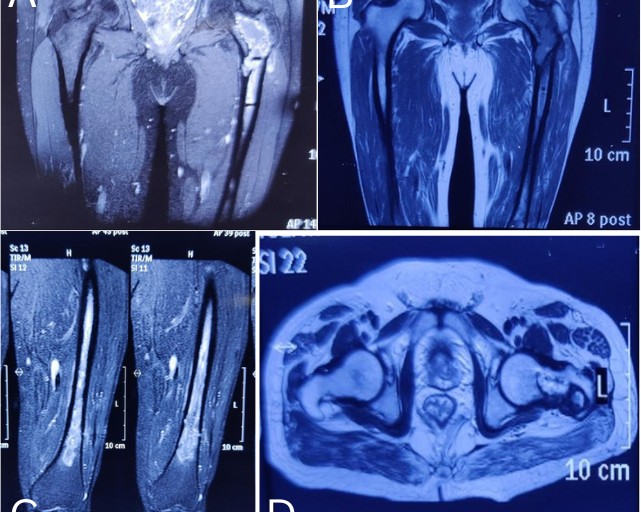

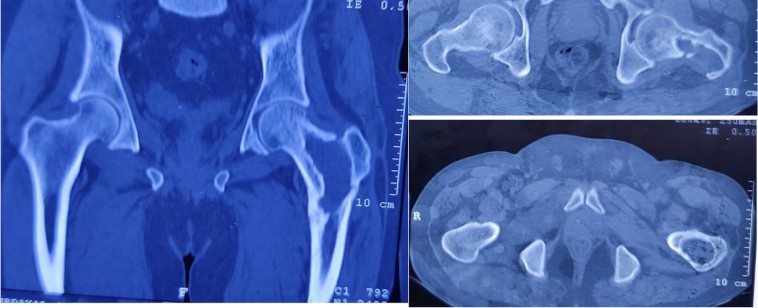

A 52-year-old male presented to our institute with complaints of pain in his left groin and thigh for 3 months. He underwent total hip replacement 4 years ago in another hospital. He had no recent history of trauma, fever, loss of appetite, or any local pus discharge. He was a known case of diabetes mellitus for the past 10 years. His pain was insidious in onset, progressive, and dull-aching in nature. He had a history of trivial trauma followed by an inter-trochanteric femur fracture that was managed with proximal femur nailing 8 years back. Three years later, he developed swelling with a discharged sinus in his left proximal thigh. Initially, it was managed with oral antibiotics. Later, he underwent 3 series of local debridement and finally implant removal. The sequence of past procedures following in chronological order: Proximal femur nailing → osteomyelitis → debridement → THA. The radiology (Fig. 1 and 2) and histopathology were suggestive of chronic osteomyelitis. However, the culture was not positive for any specific organism. Finally, his total hip was replaced after 1 year and 5 months following subsidence of infection.

Figure 1: The magnetic resonance imaging shows the osteomyelitis of the left proximal femur.

Figure 2: The computed tomography scan shows the lytic lesion in the left femur neck and trochanteric region during osteomyelitis.

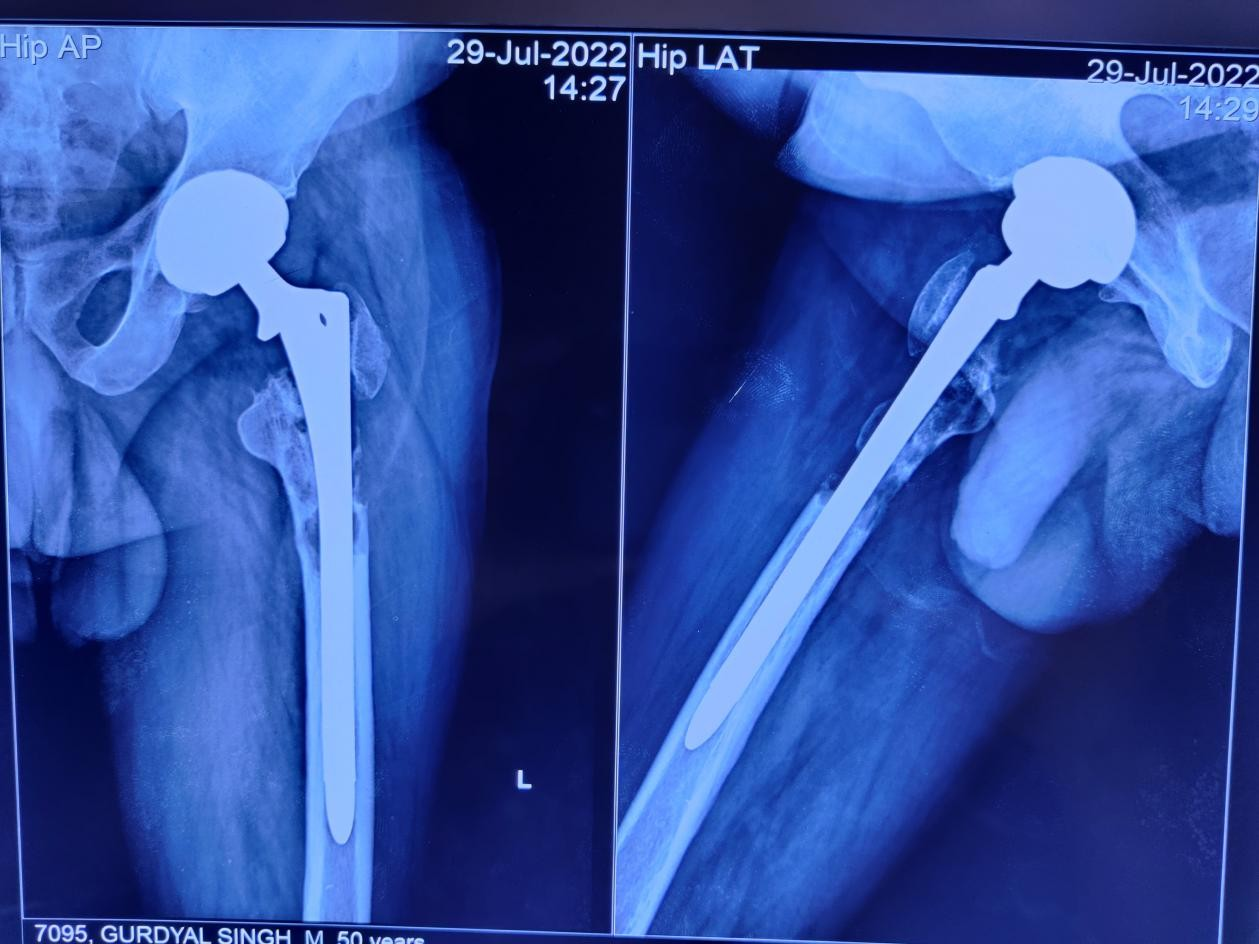

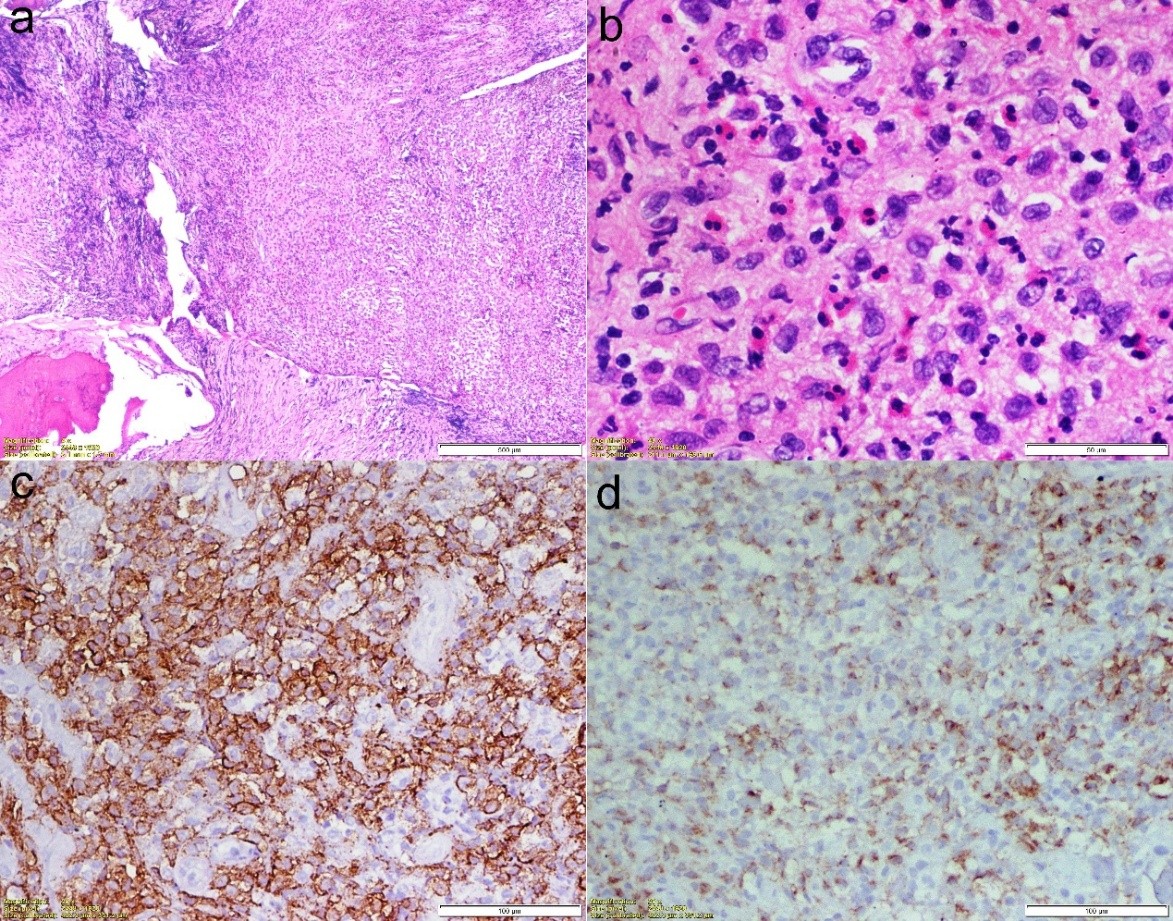

On clinical examination, he had two healed linear scars, one on the anterior proximal thigh of a size of 15 cm and another at the lateral aspect of 21 cm. There was diffuse tenderness on the left proximal thigh. There was no localized raised skin temperature, palpable swelling, and a discharged sinus. There was a true shortening of 1 cm in the left lower limb. There was no distal neurovascular deficit. A plain radiograph showed multiple lytic lesions around the proximal femoral stem 4 years following THA (Fig. 3). The magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showed a peri-prosthetic T1 hypo and T2 hyper-intense lesion around the femoral stem with a T2 hypo-intense rim and areas of the cortical breach– likely pseudo-tumor. His erythrocyte sedimentation rate was 35 mm/h, and C-reactive protein was 28.6 mg/L. A bone scan revealed no evidence of any abnormal radio-tracer uptake in the body. Fluorine-2-fluoro-2-deoxy-d-glucose positron emission tomography/computerized tomography revealed a sclerotic lesion in the upper shaft of the left femur. The MRI of the brain and ultrasound of the kidney, ureter, and bladder were normal. Our initial differential diagnosis was sequelae of chronic osteomyelitis or pseudo-tumor. A core biopsy was done under fluoroscope guidance, which revealed the fragments of bone and surrounding fibro-collagenous tissue with features of LCH. The histiocytic cells were immuno-positive with S100 protein (focal), CD1a, and Langerin (focal) as depicted in Fig. 4. The patient started with chemotherapy-injectable Vinblastine 6 g/m2 I/V bolus once weekly and Tab.

Figure 3: Depicts the peri-prosthetic lytic lesion in the left proximal femur in the anterior-posterior and lateral view of the radiograph.

Figure 4: Histopathological picture of the lesion. (a) Hematoxylin and Eosin (HE) stain (×40); (b) HE (×400); (c) CD1a stain (×200) (d) Langrin stain (×200).

Wysolone 40 mg/m2/day orally daily with a tapering dose later. It was given under the supervision of medical oncology for 6 months. We didn’t see an increase in the size of the lesion or implant loosening at 1 year follow-up. The patient was ambulatory and improved visual analogue scale score from 8 to 2.

LCH (orphan disease) refers to a spectrum of diseases characterized by idiopathic proliferation of histiocytes producing focal or systemic manifestations. It predominately affects the pediatric population with an average onset of 10–14 years of age. Arico et al., reported the mean onset of LCH in adult males is 33 years in the international registry of the Histiocyte Society, making it a rare occurrence after the fifth decade [4]. Our case was diagnosed as LCH after 8 years of initial trauma. It can involve any bone, but there is a predilection for the axial skeleton, with unifocal bone involvement being more common. We had also seen unifocal involvement with multiple scattered small lesions on the proximal femur. Wazir et al., reported a recurrent LCH case in the pelvis of a 31-year-old woman treated with THA [5]. Similarly, Pui and Jergesen described LCH in a healthy young adult man following THA for presumed idiopathic osteonecrosis [6]. They saw cystic areas in the peri-acetabular region, which could be a component of LCH and hypothesized it to spread to the femur during surgery. However, there is no mentioned case of LCH of the periarticular region after hip replacement in the elderly age group. The differentials of focal radiolucency post-hip replacement can be a feature of metallosis, implant loosening, foreign body reaction, infection, granulomatosis, or tumor. Martin et al. mentioned the sarcomatous changes in the presence of a metal implant with respect to the type of implant, latency, and tumor histology [7]. Rushforth reported the shortest latency period of 6 months post-hip replacement for osteosarcoma [8], whereas, Troop et al., stated the longest latency period of 15 years following THA for malignant fibrous histiocytoma [9]. We confirmed a benign lesion in the proximal femur, which was diagnosed 4 years after hip arthroplasty. Pavlik et al., reported a case report of osteomyelitis femur mimicking LCH in a child [10]. In the acute stage, an aggressive pattern of osteolysis and permeative destruction with a wide zone of transition, whereas the chronic stage has well-sclerotic margins and a narrow zone of transition. Its differential includes osteomyelitis, multiple myeloma, leukemia, lymphoma, Ewing’s sarcoma, and metastasis. Their typical histopathological examination shows characteristic morphologic proliferation of the Langerhans type of cell with a background of eosinophils and lymphocytes. The particular immuno-phenotypes include expressions of CD1a, S100 and langerin (CD207), and variable expressions of CD68 [11]. The histopathological and immuno-phenotyping were in favor of LCH in our case. There are different regimens and doses of glucocorticoid, immunosuppressive agents, chemotherapy, radiation, and anti-resorptive used in LCH depending on the location, number, and symptoms. Biopsy or curettage can sometimes be enough to initiate the healing process; complete surgical removal is also an option, although it may sometimes increase the healing time or leave large bone deficits that would be difficult to fill. We managed our case non-operatively with chemotherapy. Lessons learned from this case embrace the following: In cases of multiple operations, there should be a suspicion of both infection and malignancy; histopathology must be added with a special stain to confirm the diagnosis; and in cases of isolated metaphyseal lesions with a guarded prognosis, conservative treatment can be chosen for the diaphyseal fitting stem of THA.

LCH is a rare disorder and has a great potential for misdiagnosis. THA with missed LCH is a very rare entity. A prompt and vigilant attitude is paramount for making the diagnosis and achieving good clinical outcomes.

Sometimes rare diagnosis can be the first diagnosis.

References

- 1. Stull MA, Kransdorf MJ, Devaney KO. Langerhans cell histiocytosis of bone. Radiographics 1992; 12:801-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Stockschlaeder M, Sucker C. Adult Langerhans cell histiocytosis. Eur J Haematol 2006; 76:363-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Reisi N, Raeissi P, Harati Khalilabad T, Moafi A. Unusual sites of bone involvement in Langerhans cell histiocytosis: A systematic review of the literature. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2021; 16:1-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Arico M, Girschikofsky M, Généreau T, Klersy C, McClain K, Grois N. Langerhans cell histiocytosis in adults. Report from the international registry of the histiocyte society. Eur J Cancer 2003; 39:2341-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Wazir NN, Ravindran T, Mukundala VV, Choon SK. Case report: Total hip replacement for recurrent histiocytosis X of the pelvis involving hip joint. Malyas Orthop J 2007; 1:21-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Pui CM, Jergesen HE. Femoral involvement by Langerhans cell histiocytosis following total hip arthroplasty: A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93: e98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Martin A, Bauer TW, Manley MT, Marks KE. Osteosarcoma at the site of total hip replacement. A case report. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988; 70:1561-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Rushforth GF. Osteosarcoma of the pelvis following radiotherapy for carcinoma of the cervix. Br J Radiol 1974; 47:149-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Troop JK, Imallory TH, Fisher DA, Vaughn BK. Malignant fibrous histiocytoma after total hip arthroplasty. A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990; 253:297-300. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Pavlik M, Bloom DA, Özgönenel B, Sarnaik SA. Defining the role of magnetic resonance imaging in unifocal bone lesions of langerhans cell histiocytosis. J Pediatr Hematol Oncol 2005; 27:432-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Geissmann F, Lepelletier Y, Fraitag S, Valladeau J, Bodemer C, Debré M, et al. Differentiation of langerhans cells in langerhans cell histiocytosis. Blood 2001; 97:1241-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]