Synovial chondromatosis should be considered in patients with lateral ankle swelling to avoid delayed diagnosis and joint damage.

Dr. Jeff Walter Rajadurai OR, Department of Orthopaedics, Madha Medical College and Research Institute, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: jeffy.walter@gmail.com

Introduction: Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is a rare benign disorder characterized by synovial membrane metaplasia, leading to the formation of cartilaginous nodules. It commonly affects large joints, such as the knee and hip, but its occurrence in the lateral malleolus is exceptionally rare, with very few cases reported to date.

Case Report: We report the case of a 42-year-old female who presented with progressive swelling and pain over the lateral aspect of her right ankle for several months. Clinical examination revealed localized tenderness and a palpable mass over the lateral malleolus. Radiographs demonstrated calcified bodies adjacent to the lateral malleolus. The patient underwent surgical excision of the lesion. Histopathological examination revealed cartilaginous loose bodies embedded within the synovial tissue, consistent with SC. No evidence of granuloma or malignancy was found. Post-operative recovery was uneventful, and the patient remains symptom-free at follow-up.

Conclusion: SC involving the lateral malleolus is an extremely rare entity that may mimic other ankle pathologies. Early recognition, imaging, and histopathological confirmation are essential to prevent progression and recurrence. This case highlights the importance of considering SC in the differential diagnosis of chronic ankle swellings.

Keywords: Synovial chondromatosis, lateral malleolus, ankle swelling, rare case report, histopathology.

Synovial chondromatosis (SC) is not something we come across often. It’s a benign but peculiar condition where the lining of a joint – the synovium – undergoes changes and starts producing bits of cartilage. These bits sometimes float around in the joint or settle in surrounding bursae or tendon sheaths, and over time, they can harden or even turn into bone [1]. While the exact reason why this happens isn’t fully understood, what we do know is that it typically turns up in larger joints. The knee is the usual suspect, seen in nearly two-thirds of cases [1,2], followed by the hip, shoulder, and elbow.

However, when it shows up around the ankle – especially the lateral malleolus – it catches most of us off guard. That’s because it’s incredibly rare, and the signs can easily be mistaken for other, more common conditions, such as a ganglion cyst, bursitis, or even gout [3,4]. Unlike the classic presentations in the knee or hip, where joint pain, swelling, and mechanical symptoms, such as locking are more expected, SC around the ankle often presents quietly, just a subtle swelling, sometimes with minimal discomfort [4,5]. Standard X-rays may sometimes give it away, especially if the loose bodies have calcified [4]. However, in cases where nothing obvious is seen, or where soft-tissue detail matters, magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) becomes a key tool [6]. Even then, diagnosis isn’t complete without histopathology. That’s where you truly confirm it: Spotting those small cartilage nodules and the changes in the synovium under the microscope [7]. This case involves a 42-year-old woman who came in with a gradually developing swelling over her right lateral malleolus. The clinical picture wasn’t dramatic, but imaging and histopathology helped clinch the diagnosis. We’re sharing this case to highlight a condition that, although rare in this region, should still be kept in mind – particularly when the usual suspects don’t add up. Early diagnosis can go a long way in preventing chronic symptoms and recurrence.

A 42-year-old woman walked into our orthopedic outpatient department complaining of a swelling over the outer side of her right ankle. It had been slowly increasing in size over the past 3 months. She mentioned some discomfort while standing or walking for long periods, but no severe pain. There was no history of trauma, fever, or any systemic illness. She’d never had similar joint issues in the past. On examination, there was a localized swelling around the lateral malleolus, roughly 2 cm across (Fig. 1). It felt soft to firm and was mildly tender to touch. The skin over the area looked normal – no redness, no warmth. Her ankle movements were full, and there were no signs of instability, locking, or crepitus. In short, nothing about the joint itself seemed unusual, except for the presence of this firm, slow-growing lump.

Figure 1: Soft to firm swelling around 2 cm over the lateral malleolus.

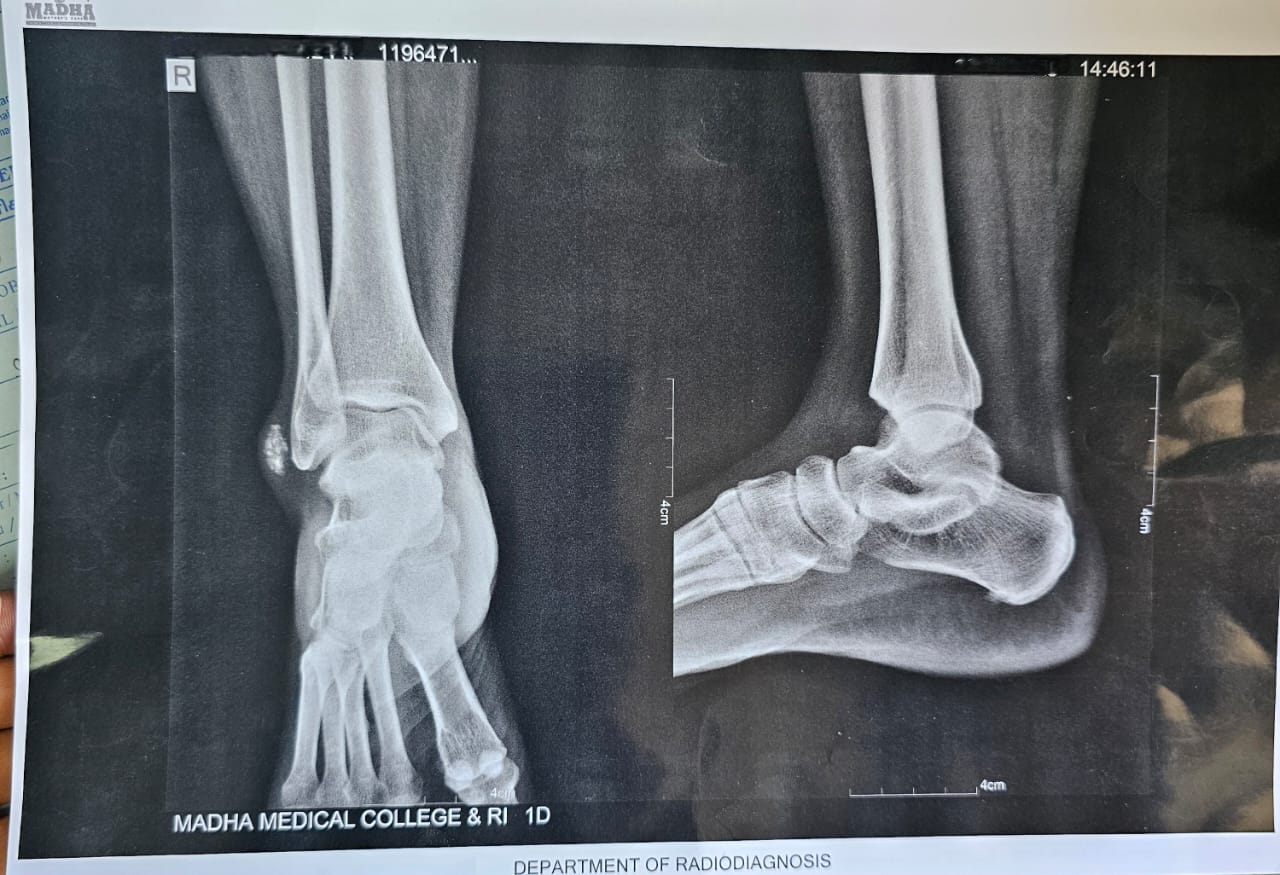

X-rays of the ankle showed a soft tissue bulge near the lateral malleolus, with a few punctate calcific specks – nothing extensive, but enough to suggest loose bodies (Fig. 2). Blood investigations were within normal limits. Based on the location and appearance, SC was kept high on the list. An MRI was done for further clarity. It picked up a subcutaneous swelling with internal areas of low signal, likely calcified, measuring around 2.1 × 0.6 × 1.5 cm, and sitting right over the lateral malleolus. The findings aligned well with what we suspected clinically.

Figure 2: X-ray showing soft tissue bulge near the lateral malleolus, with a few punctate calcific specks.

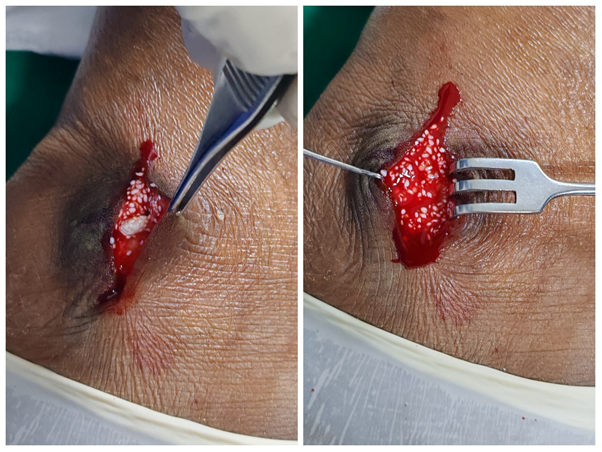

Surgery was done under spinal anesthesia. A small lateral incision was made, and as we dissected through the subcutaneous layers, we came across a firm, well-circumscribed, pale-brown mass (Fig. 3). It was sitting just superficial to the joint capsule, not involving deeper structures. On careful exposure, multiple small white loose bodies – glistening, pearl-like – were seen within the thickened synovial tissue (Fig. 4). The surrounding synovium was clearly hypertrophic and inflamed, probably from chronic irritation. Dissection was done slowly, preserving all nearby tendons and neurovascular structures. The entire mass along with the involved synovium was removed in one piece and sent for histopathology (Fig. 5).The recovery was smooth (Fig 6.)

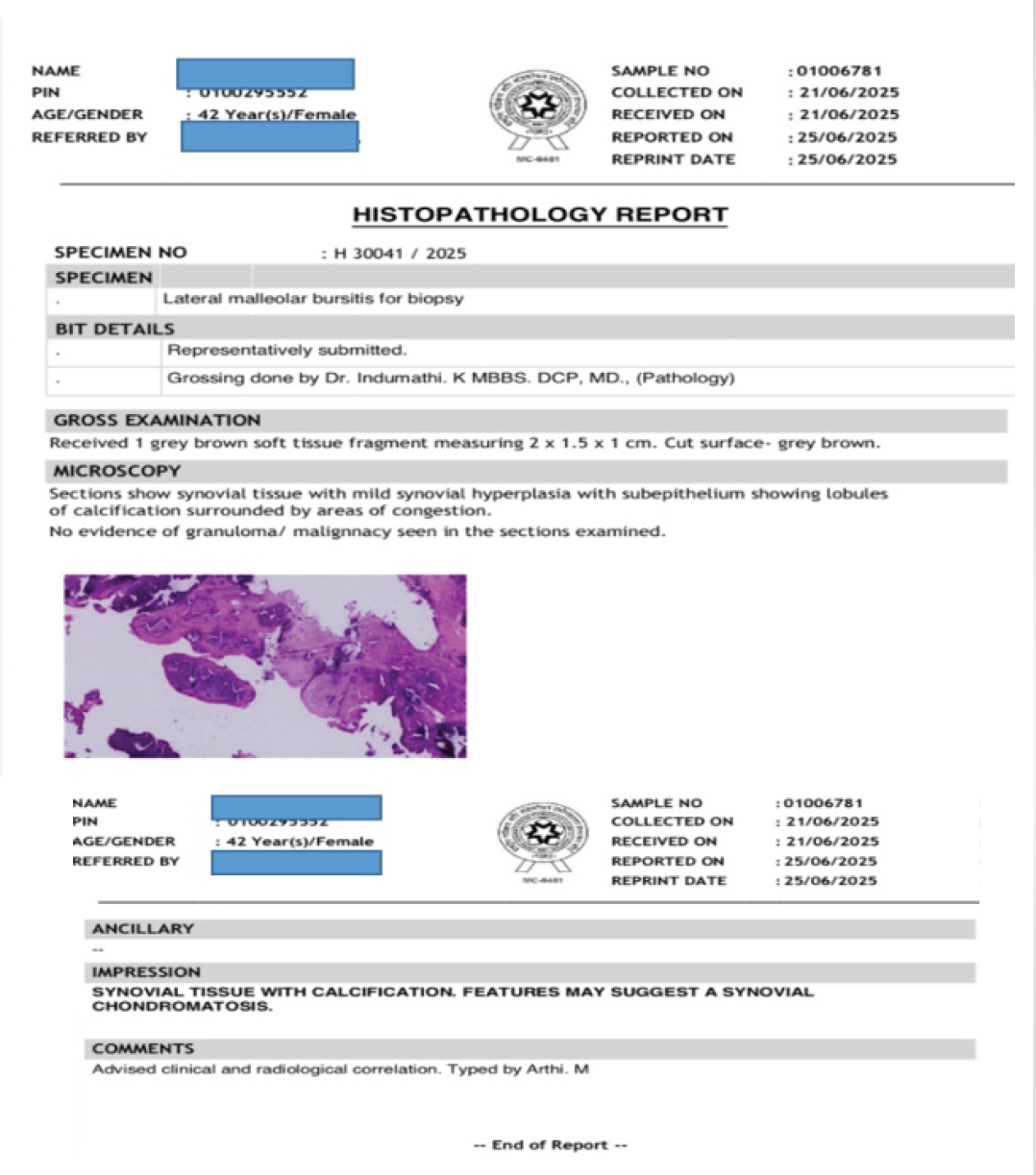

The report confirmed what we thought; mild synovial hyperplasia with lobules of cartilage, some of which were starting to calcify (Fig.7). There were no signs of granulomatous changes, malignancy, or atypical cells. The features were consistent with SC.

Figure 3: Intraoperative images showing firm, well-circumscribed, pale-brown mass.

Figure 4: Intraoperative image showing multiple small white loose bodies -glistening, and pearl-like.

Figure 5: Entire mass along with the involved synovium was removed in one piece and sent histopathology.

Figure 6: Post-operative day 3 showing sutured wound.

Figure 7: Histopathology report confirming the diagnosis.

The patient was mobilized early and discharged on day three with a compression dressing. At her 6-month review, she remained symptom-free, walking comfortably, and there were no signs of recurrence on clinical examination (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: 6th month follow up X-ray showing no recurrence.

SC is a benign metaplastic condition in which synovial tissue changes into numerous cartilaginous nodules. These nodules can break off and calcify, forming loose bodies inside or around joints [1]. It mostly affects the knee (60–70%) and hip, and it doesn’t often impact the ankle [1]. There have been a few examples of SC of the lateral malleolus, which is an extra-articular location, although they are quite rare [2,5]. SC usually happens between the ages of 30 and 50, and it affects men a little more than women [1]. Patients frequently have edema, discomfort, a limited range of motion, and mechanical symptoms, such as locking or crepitus that come on slowly [3]. In our situation, as in other cases of ankle pain, though, the symptoms may look like those of benign conditions, such as bursitis, ganglion cysts, or tenosynovitis [2,5]. When calcified loose bodies show up on ordinary radiographs, surgeons usually suspect a diagnosis; MRI is only used in cases that aren’t calcified or are unclear [4]. In our situation, just the X-rays were enough to raise suspicion; MRI was used to confirm the findings and verified by histopathology, in line with Milgram’s Phase III classification [6]. Histologically, SC is characterized by synovial hyperplasia and subepithelial hyaline cartilage nodules, which may sometimes calcify [7,8]. We didn’t find any atypia, increased cellularity, or pleomorphism in our sample, which means there was no suspicion of malignancy [7]. The routine way to treat this is to surgically remove all of the nodules and the synovium that is affected, either by an open or arthroscopic technique [4,9,10]. Arthroscopy allows for minimally invasive access, although open excision is still necessary for lesions in hard-to-reach places, such as the lateral malleolus [2,9,10]. Recurrence rates are between 7% and 23%, usually because the tumor wasn’t completely removed [3,4,9,10]. Our patient had open excision and was clear of illness even 6 months later. Our case is unique because the lesion was extra-articular, located over the lateral malleolus, whereas most published cases describe intra-articular disease. In such instances, arthroscopy is an excellent option for intra-articular SC as shown by Moorthy et al. [11], offering minimally invasive removal of loose bodies and synovectomy. However, in our patient, the pathology was subcutaneous and directly over the lateral malleolus; so open excision provided better exposure and ensured complete clearance, consistent with the approach ultimately required by Gholipour et al. [12] when arthroscopy proved inadequacy The differential diagnoses in our case included ganglion cyst, bursitis, gouty tophus, tenosynovitis, and even rare entities, such as synovial sarcoma. These are similar to the considerations highlighted in other reports, including Yadav et al. [13] in a pediatric ankle presentation. In our patient, the presence of punctate calcifications on radiographs, corroborated by MRI and confirmed histologically, established the diagnosis of SC. Finally, we recognize that primary SC (Reichel’s syndrome) carries a recurrence risk, even after apparently successful excision. Gatt and Portelli [14] reported recurrence within 9 months following surgical removal. While our patient remains recurrence-free at 6 months, we have planned long-term follow-up for at least 2 years to monitor for possible recurrence and ensure timely management if required. Thus, compared with prior literature, our case underscores that open excision remains the most appropriate strategy for extra-articular lateral malleolar lesions, with due attention to differential diagnosis and commitment to extended surveillance given the possibility of Reichel’s syndrome.

SC of the lateral malleolus is a remarkably rare entity that may be misdiagnosed due to its atypical presentation. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion in patients with persistent lateral ankle swellings. Diagnosis can often be established through radiographs and confirmed histologically. Complete surgical excision is essential to prevent recurrence and ensure symptomatic relief.

Synovial chondromatosis can present at uncommon sites, such as the lateral malleolus, surgeons should maintain a high index of suspicion, confirm diagnosis histologically, and follow-up to prevent recurrence.

References

- 1. Saxena A, St Louis M. Synovial chondromatosis of the ankle joint: Report of two cases with 23 and 126 loose bodies. J Foot Ankle Surg 2017;56:182-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Sedeek SM, Choudry Q, Garg S. Synovial chondromatosis of the ankle joint: Clinical, radiological, and intraoperative findings. Case Rep Orthop 2015;2015:359024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Galat DD, Ackerman DB, Spoon D, Turner NS, Shives TC. Synovial chondromatosis of the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 2008;29:312-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Monestier L, Riva G, Stissi P, Latiff M, Surace MF. Synovial chondromatosis of the foot: Two case reports and literature review. World J Orthop 2019;10:404-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Shearer H, Stern P, Brubacher A, Pringle T. A case report of bilateral synovial chondromatosis of the ankle. Chiropr Osteopat 2007;15:18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Milgram JW. Synovial osteochondromatosis: A histopathological study of thirty cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1977;59:792-801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Davis RI, Hamilton A, Biggart JD. Primary synovial chondromatosis: A clinicopathologic review and assessment of malignant potential. Hum Pathol 1998;29:683-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Maurice H, Crone M, Watt I. Synovial chondromatosis. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:807-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Doral MN, Uzumcugil A, Bozkurt M, Atay OA, Cil A, Leblebicioglu G, et al. Arthroscopic treatment of synovial chondromatosis of the ankle. J Foot Ankle Surg 2007;46:192-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Lim SJ, Chung HW, Choi YL, Moon YW, Seo JG, Park YS. Operative treatment of primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the hip. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:2456-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Moorthy V, Tay KS, Koo K. Arthroscopic treatment of primary synovial chondromatosis of the ankle: A case report and review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2020;10:54-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Gholipour M, Salimi M, Motamedi A, Abbasi F, Behnam B, Sadr SR. Primary synovial chondromatosis of the ankle: A case report with radiologic and imaging findings. Radiol Case Rep 2024;20:1637-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Yadav SK, Rajnish RK, Kumar D, Khera S, Elhence A, Choudhary A. Primary synovial chondromatosis of the ankle in a child: A rare case presentation and review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2023;13:5-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Gatt T, Portelli M. Recurrence of primary synovial chondromatosis (Reichel’s syndrome) in the ankle joint following surgical excision. Case Rep Orthop 2021;2021:9922684. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]