Sagittal spino-pelvic radiograph should be obtained to understand the interplay between the spinal regions rather than looking at a single segment alone.

Dr. Sudhir Singh, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: susi59@live.in

Introduction: Chronic neck pain is a common musculoskeletal condition characterized by persistent pain in the neck lasting more than 3 months. The natural lordotic curvature of the cervical spine can impact the stability of the cervical vertebrae, and alterations to this curvature can lead to neck pain and disability. Our primary objective was to investigate the association of cervical lordosis with neck pain. Secondarily, we also examined the relationship of Cobb’s angle and Jackson physiological stress (JPS) angle with age, gender and BMI.

Methods: This prospective cross-sectional study included 255 adult patients of either gender having neck pain. The patients were stratified into three groups. Neck pain cases without radiation to upper limb were categorised as group I, those with radiation to upper limb as group II and those with neck pain with radiculopathy/ myelopathy as group III. Lateral projection radiograph of cervical spine was obtained for all subjects. Cobb’s angle (C2-C7) & Jackson physiological stress (JPS) angle were measured using DICOM software.

Results: Neck pain cases in group I included 93 cases, group II had 98 cases and group III had 64 cases. The mean cervical lordosis as measured by Cobb’s angle was 27.24 ± 9.17 degrees and by JPS angle was 30.65 ± 10.39 degrees (P<0.0001). Both, Cobb’s and JPS angle were similar in all age groups, gender and BMI subcategories (Cobb’s angle: p= 0.631, p=0.156, p=0.61; JPS angle: p=0.396, p=0.0804, p=0.539) respectively. The degree of lordosis was similar in all three pain sub-type when measured by Cobb’s method (p=0.969) or by JPS angle (p=0.952).

Conclusion: The study found that cervical lordosis (Cobb’s angle and Jackson physiological stress angle) has no association with cases having neck pain with or without radiation to upper limbs or neck pain with radiculopathy/ myelopathy. Cervical lordosis does not vary significantly with age, gender and BMI irrespective of the method used.

Keywords: Cervical lordosis, Cobb’s angle, Non-specific neck pain, Jackson physiological stress angle, Neck pain.

Chronic neck pain is a common musculoskeletal condition and is characterized by persistent pain in the neck lasting beyond than 3 months [1]. Around 30% to 50% of middle-aged and elderly individuals suffer from it and impacting their overall quality of life [2]. Despite its benign nature, it has significant socioeconomic implications including reduced productivity as well as job-related difficulties [3]. Globally, an age-fixed rate of prevalence is reported as being 3551.1 & rate of incidence as 806.6 per one lac of neck pain patients has been reported [3]. In India the prevalence rate has been reported as 18.6% [1]. The natural wedge shape of cervical vertebrae allows the cervical spine to maintain a lordotic curve to compensate for thoracic kyphotic curve [4,5]. Any alterations to this natural lordotic curvature can impact the stability of the cervical vertebrae [6]. The cervical spine in asymptomatic individual usually exhibits a lordotic shape, but it has been reported that up to 35% of cases can display kyphotic curve [7]. Alterations in the cervical curve, such as straightening or kyphosis, have been linked to neck pain, myelopathy and disability [4]. It has been reported that lordosis less than 20 degrees correlates with cervical pain, and “clinically normal” normal range of 31-40 degrees for cervical lordosis was suggested [8]. However, other researchers have suggested that neck pain characteristics do not influence global or segmental cervical spine curves [9]. Our primary objective was to investigate the association of cervical lordosis with chronic neck pain. Secondarily, we also examined the association of cervical lordosis with age, gender and BMI as assessed by Cobb’s angle and JPS angle.

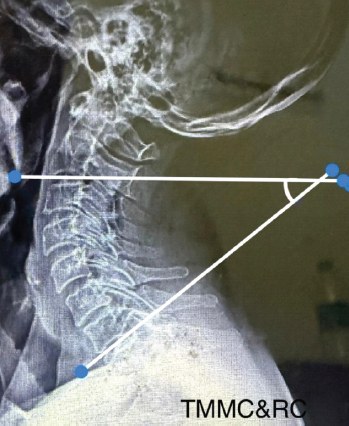

This prospective and cross-sectional study was conducted in the orthopaedic department of a tertiary health care center. The study included 255 adult patients with age above 18 years of either gender with neck pain attending the outpatient department during December 2023 till May 2025. The study was conducted after approval from the College research committee (CRC) and Institutional Ethics Committee (IEC) (approval no.: TMU/IEC No. 23/116). A written informed consent was obtained from all subjects. Our study is a cross-sectional study (level IV evidence). The study was carried out as per the standards laid down in the Helsinki Declaration (1964) and its amendment (2013). The patients were stratified into three groups. Neck pain cases without radiation to upper limb were categorised as group I, those with radiation to upper limb as group II and those with neck pain with radiculopathy/ myelopathy as group III. Patients with a history of trauma, previous surgery, inflammatory or infective pathology, degenerative joint disease and congenital conditions of the cervical spine or shoulder were excluded. Patients were evaluated by detailed history taking, examination and relevant investigations. A standard lateral radiograph of cervical spine was done in a comfortable standing position with upper extremities positioned naturally at the side of body, maintaining horizontal gaze. Cobb’s angle (C2-C7) and Jackson physiological stress (JPS) angle was measured on a plain radiograph in lateral view of cervical spine using DICOM software, by a radiologist who was blinded to clinical findings. The Cobb’s angle was measured as the angle between the tangential line inferior endplate of the second vertebra (C2) and another line tangential to the inferior end plate of seventh vertebra (C7) (Figure 1 ) [10]. The Jackson physiological stress angle was measured between drawing a tangential line on the posterior surface of the second cervical vertebra (C2) and another tangential line drawn on the posterior surface of seventh cervical vertebra (C7). The angle of intersection between these two lines is Jackson physiological stress (JPS) angle (Figure 2) [10]. Both angles were measured using lateral radiographs and DICOM software, allowing for precise calculations. MRI Cervical spine was done to confirm the diagnosis of Radiculopathy/ myelopathy if needed.

Figure 1: The Cobb angle is measured as the angle between the tangent on the inferior endplate of the second vertebra (C2) and the tangent on the inferior endplate of the seventh vertebra (C7).

Figure 2: The Jackson physiological stress angle is measured between the tangent on the posterior surface of the second cervical vertebra (C2) and the tangent on the posterior surface of the seventh cervical vertebra (C7).

Statitistical analysis was performed using SPSS (Statitistical Package for Social Sciences) software version 22. Data was represented by frequency/percentages, mean and SD. Chi-square test was used to check significance. P<0.05 was taken as significance level.

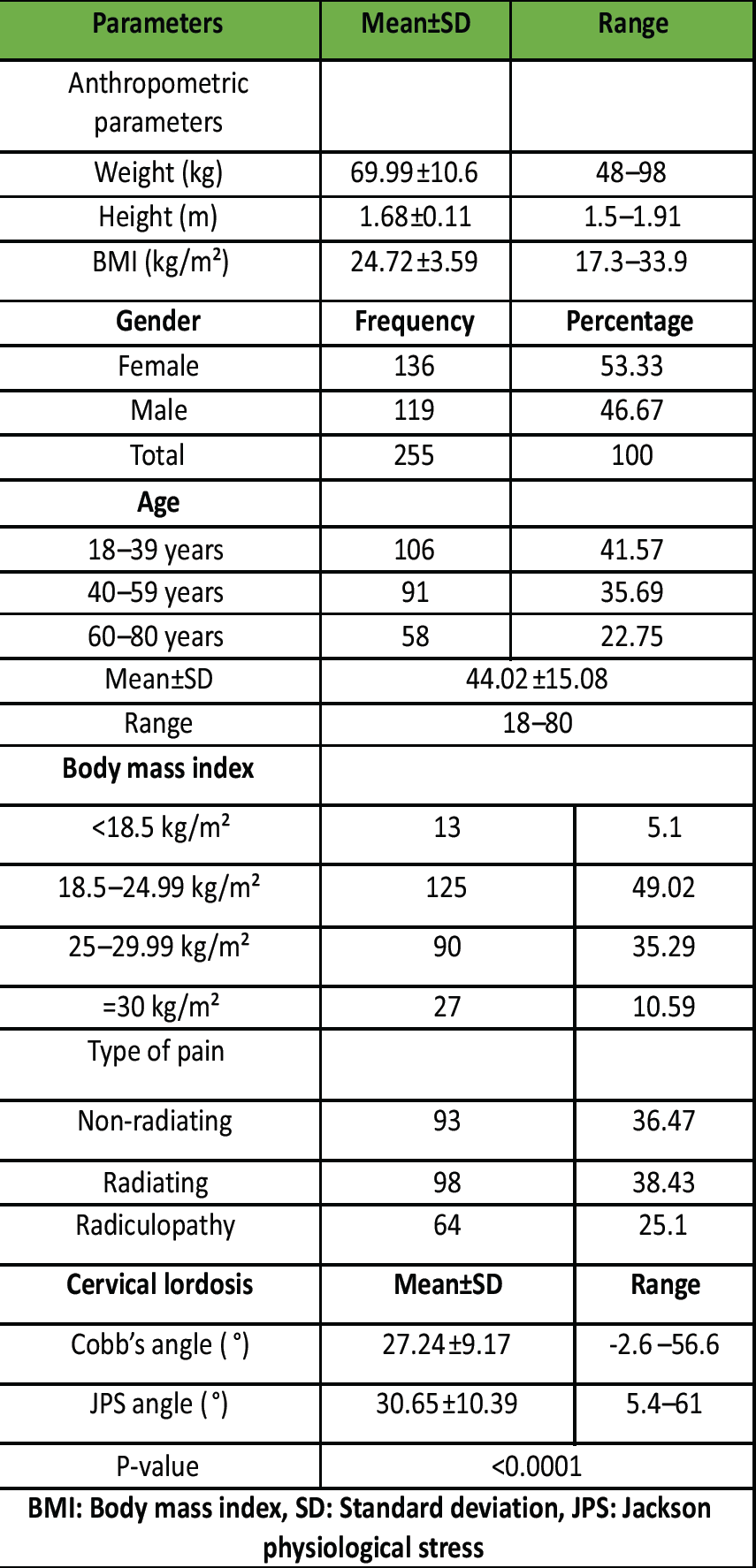

Demographic Profile: The study population comprised of 255 subjects (Group I: 93 cases, Group II: 98 cases and Group III: 64 cases). None of the study subjects had concomitant thoracic or lumbar spine pain. The study subjects included 136 females (53.33%) and 119 males (46.67%), with a mean age of 44.02 ± 15.08 years (range: 18-80 years). There were 106 (41.57%) cases in18-39 years age group, 91 (35.69%) cases in 40-59 years age group and 58 (22.75%) cases in 60-80 years age group. The study population had a mean BMI was 24.72±3.59 kg/m² (range: 17.3-33.9 kg/m²). BMI sub-categories included 13 cases (5.10%) in underweight, 125 cases (49.02%) in normal, 90 cases (35.29%) in overweight and 27 cases (10.59%) in obese sub-category. There were 93 cases (36.47%) with non-radiating pain, 98 cases (38.43%) with radiating pain and 64 cases (25.10%) with complaints of radiculopathy/ myelopathy. The cervical lordosis as measured by Cobb’s angle was 27.24 ± 9.17 degrees (range: -2.6-56.6) and by JPS angle was 30.65 ± 10.39 degrees (range: 5.4-61) (P<0.0001) (Table 1).

Table 1: General descriptive statistics of study subjects

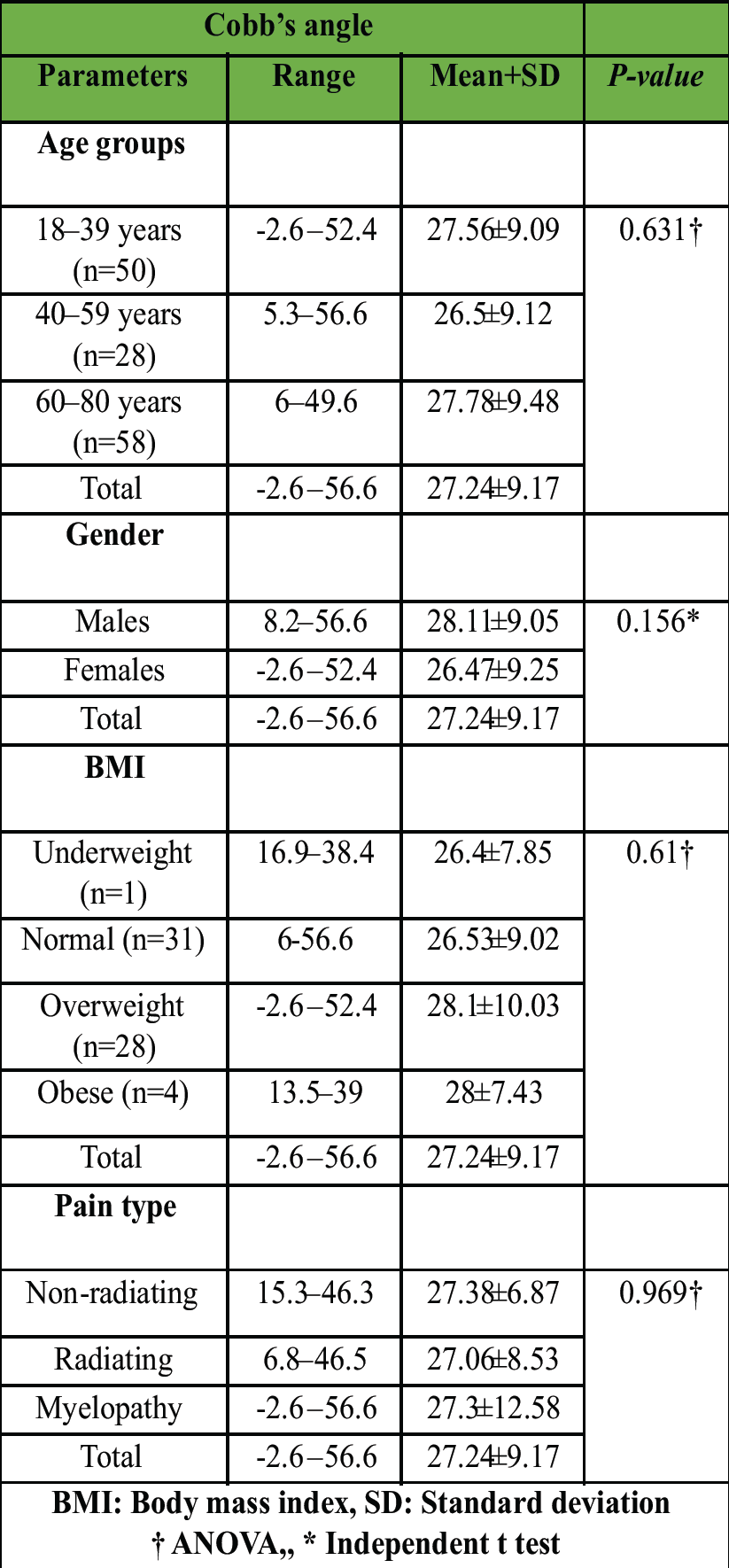

Association of Cobb’s angle with demographic and clinical variables: The Cobb’s angle was 27.56±9.09 in 18-39 years age group , 26.5±9.12 in 40-59 years age group and 27.78 ±9.48 degrees in 60-80 years age group showing no statistical difference (p=0.631). Male subjects (28.11±9.05) had insignificantly higher values than females (26.47±9.25) (P=0.156). Analysis of BMI sub-categories revealed insignificant differences (p=0.61) between underweight (26.4±7.85), normal (26.53±9.02), overweight (28.1±10.03) and obese (28 ±7.43) sub-categories. Pain type also did not significantly influence Cobb’s angle (p=0.969) in cases with non-radiating pain (27.38±6.87), with radiating pain (27.06±8.53) and myelopathy group (27.3±12.58) showing similar values. (Table 2)

Table 2: Association of Cobb’s angle with variables

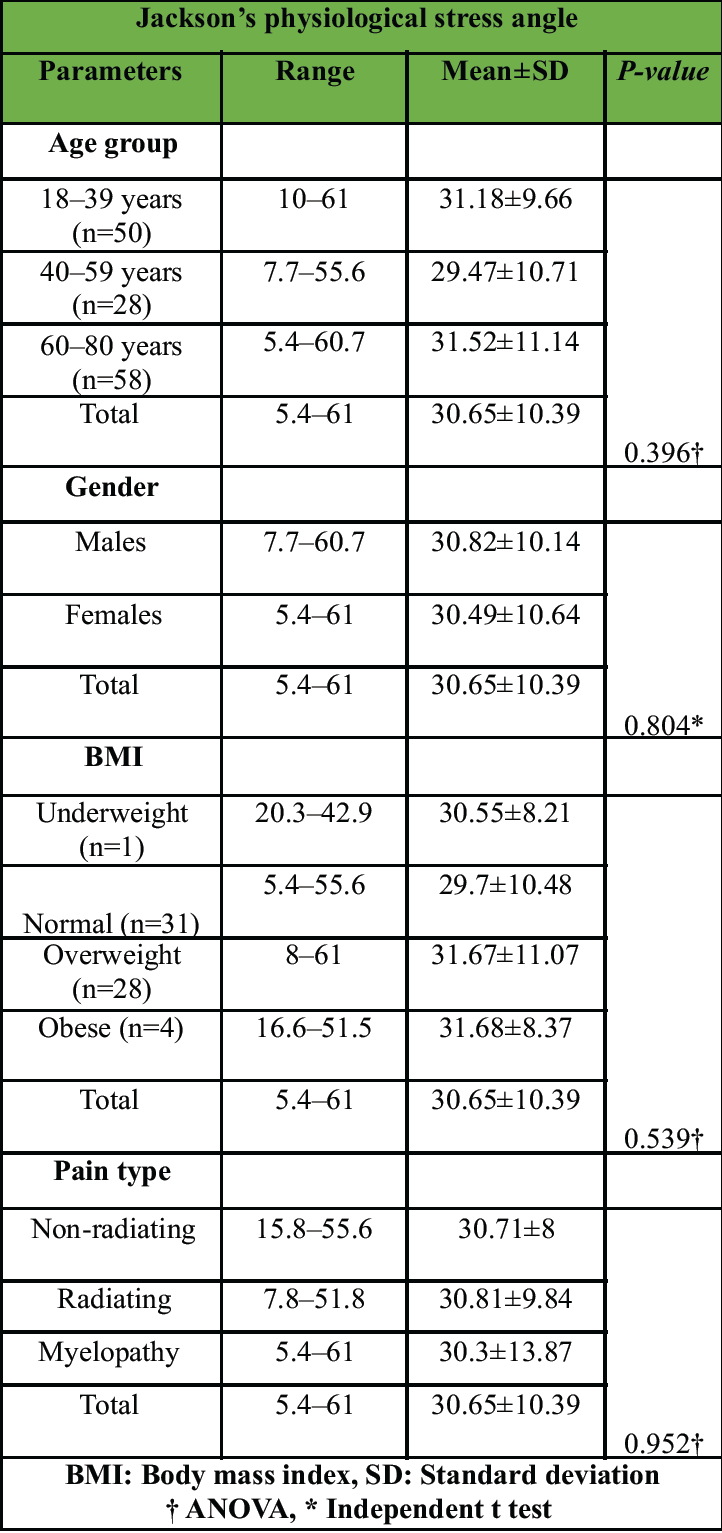

Association of JPS angle with demographic and clinical variables: The JPS angle was recorded as 31.18±9.66 in 18 to 39 years age-group, as 29.47±10.71in 40 to 59 years age-group and as 31.52±11.14 degrees in 60 to 80 years age-group with insignificant difference (p=0.396) between values. Angle of lordosis in male subjects (30.82±10.14) and female subjects (30.49±10.64) was also similar (p=0.0804). BMI sub-categories also did not show any statistically significant difference (underweight: 30.55±8.21, normal: 29.7±10.48, overweight: 31.67±11.07 and obese: 31.68 ±8.37; p=0.539). Similarly, pain type also did not influence JPS angle (p=0.952) in cases with non-radiating pain (30.71±8), with radiating pain (30.81±9.84) and myelopathy group (30.3±13.87) showing similar values. (Table 3)

Table 3: Association of Jackson’s Physiological Stress angle with variables

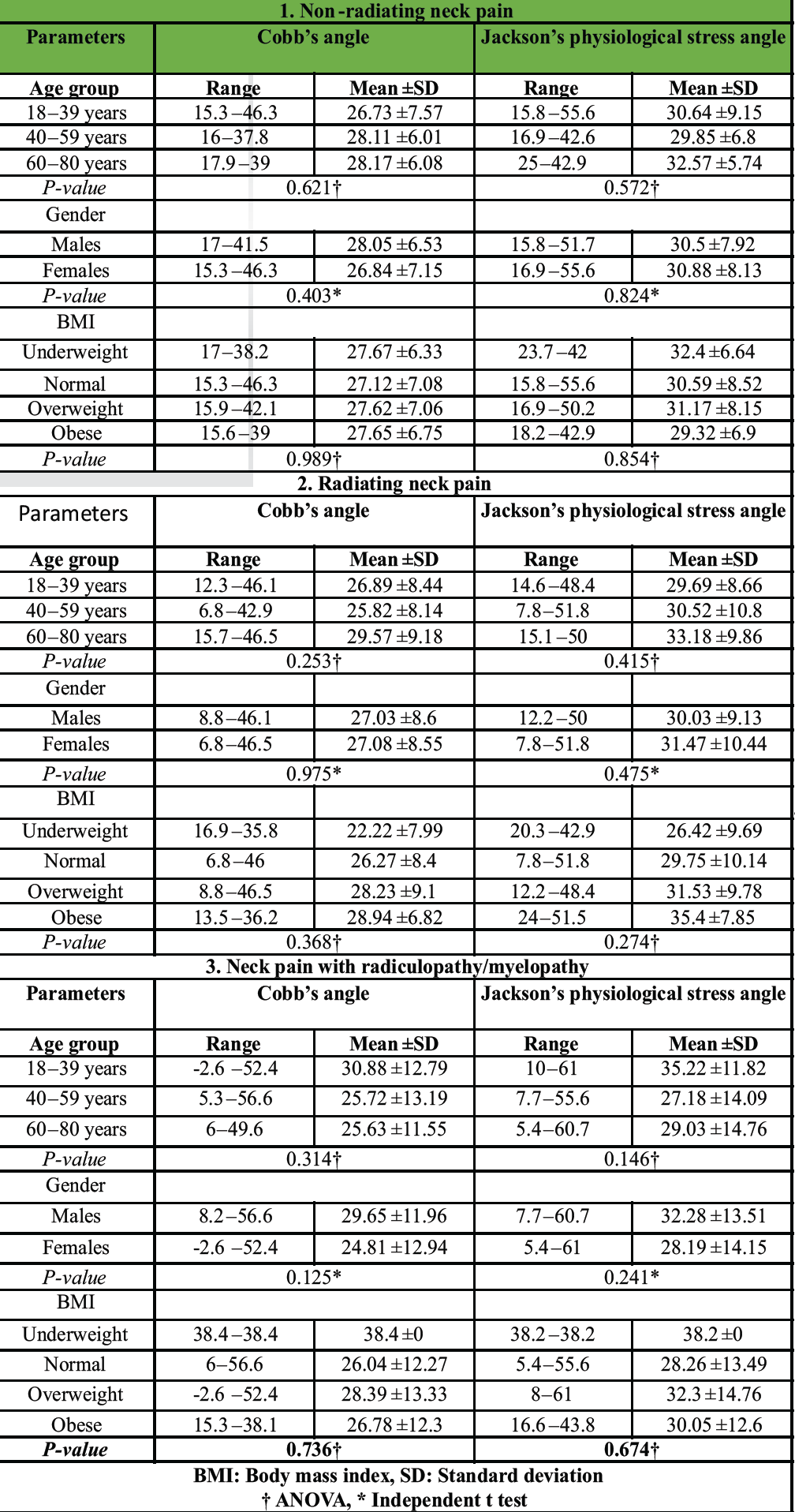

Association of Pain with Cobb’s and JPS angle: The whole data set was relooked in all three pain categories e. non-radiating, radiating and with myelopathy groups. In non-radiating pain group, both Cobb’s and JPS angle (p=0.621, p=0.572) were similar across all age-groups (p=0.621,p=0.572), gender (p=0.403, p=0.824) and in BMI sub-categories (p=0.989, p=0.854). In radiating pain group both Cobb’s and JPS angle showed similar values when degree of lordosis was measured between various age-groups (p=0.253, p=0.415), gender (p=0.975, p=0.475) and BMI sub-categories (p=0.368, p=0.274). Similarly in radiculopathy/ myelopathy group as well Cobb’s and JPS angle did not vary significantly across different age-groups (p=0.314, p=0.146), male and females (p=0.125, p=0.241) and in BMI sub-categories (p=0.736, p=0.674). (Table 4)

Table 4: Association of Type of Pain with Age groups, Gender and BMI

The aim of this research was to study the relation of cervical spine alignment as measured by two methods (C2-C7 Cobb’s angle and JPS angle) with neck pain. We chose C2-C7 Cobb’s angle and JPS angle as two parameters to assess cervical lordosis as they are most reliable and commonly used parameters [6]. The relationship between cervical pain and sagittal cervical alignment is still not conclusively established [11]. Though, it is generally accepted that cervical spine has a lordotic curve, yet 35% of asymptomatic population show kyphotic curve [7]. The mere presence of structural variations cannot be termed as an abnormal radiological finding and be linked as a causative factor for neck pain [7,9]. Further, it has been reported and generally accepted that cervical lordosis depends on thoracic and lumbar lordosis and their changes as a compensatory response to changes in thoracic and lumbar curvature [6]. The “clinically normal” range of cervical lordosis was first suggested as 310-400 and less than 200 of lordosis was said to be significantly associated with neck pain [8]. Subsequently, Grob in 2007 quantified kyphotic spine as having more than 40, lordotic spine as less than 40 and straight spine as those having +40 to -40 of lordosis [9].

Demographic profile: The variations in lordotic angle in asymptomatic or healthy individuals with age, gender and BMI and has been reported by many published reports. Cervical lordosis increases with age and is more in males [2,6,12-14] but there are contradicting reports as well [9,15-17]. The general consensus is that lordosis increases with age and is more in males. But, in our study, we did not find any statistically significant difference values of cervical lordosis between any age sub-group (p=0.631), gender (p=0.156) and BMI sub-category (p=0.61) when measured by Cobb’s method signifying that cervical lordosis is independent of age, gender and BMI. (Table 2) Similarly, when JPS angle was measured to assess lordosis, again, we did not find any significant variations of lordotic angles in different age sub-group (p=0.396), gender (p=0.804) and BMI sub-category (p=0.539). (Table 3) These data suggests that cervical lordosis angle is independent of age, gender and BMI. It has been reported that obesity influences global spinal parameters rather than local cervical measures, with pelvic and lower limb adaptations compensating for added weight [18]. This suggests that the cervical spine remains unaffected by BMI in isolation. Our study also did not show any relation of BMI in any sub-category of age, gender and pain as reported earlier as well [15]. Hence, we conclude that there is no relation of cervical lordosis with age, gender and BMI, irrespective of which method was used (Cobb’s method or JPS angle) method was used to assess the lordotic angle. On comparison of cervical lordosis values given by C2-C7 Cobb’s angle (27.24°±9.17°) method and Jackson physiological stress angle (30.65°±10.39°) method, our study revealed significant differences between these two (p<0.0001). JPS angle gives higher values of lordosis than Cobb’s method has been reported earlier where the authors has compared Cobb’s C0-C2, Harrison, Cobb’s and JPS angle method. They have stated that Cobb’s technique overestimates cervical lordosis at C0-C2 level and underestimate at C2-C7 level [19,20].

Pain profile and lordosis:

There are many risk factors reported for neck pain and hence, it has been labeled as a multifactorial disease [3]. The risk factors have been categorized as a) Psychological causes (depression, stress, anxiety, cognitive variables, sleep problem, social support, personality and behavior), b) Biological causes (neuro-musculoskeletal disorder, autoimmune diseases, genetic, gender, age) and c) Individual causes (work related, work place related) [3]. Recently, overuse of computer and mobile phone has also been recognized as an individual risk factor. One author in his review article has stated that most risk factors for neck pain are pshychosocial and not physical [21]. Relation of cervical pain and lordosis is highly controversial. Since last two to three decades many researchers are trying to answer the two basic questions: 1) Is the angle of lordosis is actually related to cervicalgia, and 2) Alterations of cervical lordosis is the “cause” or “effect” of neck pain. There are many published reports in support of and against of these hypotheses. Many authors after their study with asymptomatic and symptomatic individuals and few meta-analysis have denied any relation of cervical lordosis with neck pain [2,7,9,15,16] but, some others have reported significant association of neck pain with lordotic angle. McAviney J reported a significant association neck pain with cervical lordosis of less than 200 [8]. Delen V in a cross-sectional study on chronic neck pain patients with and without loss of cervical lordosis, stated that both groups were similar with respect to age, gender, employment status and duration of pain but, the group with loss of lordosis has a longer duration of headache than the group without loss of lordosis [22]. Seo YN in his study with young soldiers, stated that cervical lordosis is similar in those with and those without neck pain when Cobb’s (C2-C7) technique is used (p=0.821) but, when JPS angle technique is used the two groups show significant difference in lordotic angle (p=0.011) [11]. This emphasizes the point that lordotic angle would be different with different techniques used. In our study, we have used both Cobb’s and JPS angle to assess the lordosis. In the present study, in non-radiating pain group, both Cobb’s and JPS angle did not vary significantly in sub-groups of age (p=0.621, p=0.572), gender (p=0.403, p=0.824) and in BMI (p=0.989, p=0.854). Also in radiating pain group both Cobb’s and JPS angle showed similar values of lordosis between sub-groups of age (p=0.253, p=0.415), gender (p=0.975, p=0.475) and BMI (p=0.368, p=0.274). Similarly in radiculopathy/ myelopathy group as well both, Cobb’s and JPS angle did not vary significantly among sub-groups of age (p=0.314, p=0.146), gender (p=0.125, p=0.241) and in BMI (p=0.736, p=0.674)(Table 4). Gender and BMI did not affect alignment measures, paralleling previous research. The absence of such demographic influence is noteworthy, given the lack of similar studies for direct comparison. Most studies, whether observational, cross-sectional or longitudinal, with asymptomatic volunteers or with patients having neck pain conclude that no correlation of cervical lordosis and cervicalgia exists [2,7,9,15,16]. There is only handful of reports stating definite correlation of cervical lordosis with age, gender and cervicalgia but they fail to give any explanation as to whether the change in lordotic curve is the “cause” of cervicalgia or it is the “effect” of cervicalgia [2,8,12,14]. Further, in cases where the patient has been treated with spinal manipulation and or physiotherapeutic exercises and in those who have undergone surgical procedure to correct sagittal alignment of cervical spine, surgical outcomes were more related to symptoms and functional scores than alignment changes. [17,23-25]. It seems logical to believe that abnormalities of cervical curvature in a neck pain patient should be considered coincidental, as stated by Gorb [9] and the amount of lordosis should not be taken as a point favoring any pathology. However, in our present study we could demonstrate any relationships between age, gender, BMI and cervical lordosis values with pain. This prompts us to look further in to pain mechanisms, which may involve additional factors beyond cervical alignment. It has been reported that wherever possible, radiographic studies of the whole spine has to be obtained for deeper understanding of the interplay between the spinal regions much rather than looking at a single region on its own [26]. Overall, the study concludes that age, gender, and BMI do not significantly influence cervical alignment parameters (Cobb’s angle & JPS angle) in patients with various neck pain types, including radiculopathy/myelopathy. Further research is needed to understand the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck pain and factors beyond sagittal cervical alignment are likely more crucial in determining symptoms.

In conclusion, this study found no association between Cobb’s angle or Jackson physiological stress angle with neck pain, suggesting that cervical lordosis may not be a reliable indicator of neck pain. The study also revealed that both, Cobb’s angle and Jackson physiological stress angle methods are equally reliable and give similar results across all age groups, gender or BMI categories, indicating that these demographic factors may not have a significant impact on cervical spine alignment parameters.

The clinical message is that degree of cervical lordosis has no relation with neck pain with or without radiation to upper limb and with radiculopathy/ myelopathy and is independent of age, gender and BMI.

References

- 1. Sidiq M, Ramachandran A, Kashoo FZ, Yadav M, Shaphe MA, Ahluwalia G, Khan S, Sahu RK. Prevalence of chronic non-specific neck pain and its associated risk factors among adults in Mathura, India. NeuroQuantology. 2022;20(10):3210. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Gao K, Zhang J, Lai J, Liu W, Lyu H, Wu Y, Lin Z, Cao Y. Correlation between cervical lordosis and cervical disc herniation in young patients with neck pain. Medicine (Baltimore). 2019 Aug;98(31):e16545. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kazeminasab S, Nejadghaderi SA, Amiri P, Pourfathi H, Araj-Khodaei M, Sullman MJ, Kolahi AA, Safiri S. Neck pain: global epidemiology, trends and risk factors. BMC musculoskeletal disorders. 2022 Dec;23:1-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Scheer JK, Tang JA, Smith JS, Acosta FL, Protopsaltis TS, Blondel B, Bess S, Shaffrey CI, Deviren V, Lafage V, Schwab F. Cervical spine alignment, sagittal deformity, and clinical implications: a review. Journal of Neurosurgery: Spine. 2013 Aug 1;19(2):141-59. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Gay RE. The curve of the cervical spine: variations and significance. Journal of manipulative and physiological therapeutics. 1993 Nov1;16(9):591-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Ames CP, Blondel B, Scheer JK, Schwab FJ, Le Huec JC, Massicotte EM, Patel AA, Traynelis VC, Kim HJ, Shaffrey CI, Smith JS. Cervical radiographical alignment: comprehensive assessment techniques and potential importance in cervical myelopathy. Spine. 2013 Oct 15;38(22S):S149-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Gore DR, Sepic SB, Gardner GM. Roentgenographic findings of the cervical spine in asymptomatic people. Spine. 1986 Jul 1;11(6):521-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. McAviney J, Schulz D, Bock R, Harrison DE, Holland B. Determining the relationship between cervical lordosis and neck complaints. J Manipulative Physiol Ther. 2005 Mar-Apr;28(3):187-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Grob D, Frauenfelder H, Mannion AF. The association between cervical spine curvature and neck pain. European Spine Journal. 2007 May;16:669-78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Rajesh R, Rajasekaran S, Vijayanand S. Imaging in cervical myelopathy. Indian Spine Journal. 2019 Jan 1;2(1):20-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Seo YN, Yu JW, Yun DJ, Kwon YM, Lee SM. The Association Between Cervical Spine Alignment and Neck Axial Pain in Early Twenties Soldiers. Asian Journal of Pain. 2019 Oct 31;5(1):1-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Yukawa Y, Kato F, Suda K, Yamagata M, Ueta T. Age-related changes in osseous anatomy, alignment, and range of motion of the cervical spine. Part I: radiographic data from over 1,200 asymptomatic subjects. Eur Spine J. 2012;21(8):1492–1498. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Iorio J, Lafage V, Lafage R, et al. The effect of aging on cervical parameters in a normative North American population. Global Spine J 2018;8:709–15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Tang R, Ye IB, Cheung ZB, Kim JS, Cho SK. Age-related changes in cervical sagittal alignment: a radiographic analysis. Spine (Phila Pa 1976). 2019;44(19):E1144–E1150. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Kim JH, Kim JH, Kim JH, Kwon TH, Park YK, Moon HJ. The relationship between neck pain and cervical alignment in young female nursing staff. Journal of Korean Neurosurgical Society. 2015 Sep 30;58(3):231-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Guo GM, Li J, Diao QX, Zhu TH, Song ZX, Guo YY, Gao YZ. Cervical lordosis in asymptomatic individuals: a meta-analysis. Journal of orthopaedic surgery and research. 2018 Dec;13(1):1-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Iyer S, Lenke LG, Nemani VM, et al. Variations in occipitocervical and cervicothoracic alignment parameters based on age: a prospective study of asymptomatic volunteers using full-body radiographs. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2016;41:1837-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Jalai CM, Diebo BG, Cruz DL, et al. The impact of obesity on compensatory mechanisms in response to progressive sagittal malalignment. Spine J 2017;17:681-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Yuceli S, Yaltirik CK. Cervical spinal alignment parameters. The Journal of Turkish Spinal Surgery. 2019 Jul 1;30(3):181-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Harrison DE, Harrison DD, Cailliet R, Troyanovich SJ, Janik TJ, Holland B. Cobb method or Harrison posterior tangent method: which to choose for lateral cervical radiographic analysis. Spine. 2000 Aug 15;25(16):2072-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Kim R, Wiest C, Clark K, Cook C, Horn M. Identifying risk factors for first-episode neck pain: A systematic review. Musculoskeletal Science and Practice. 2018 Feb 1;33:77-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Delen V, İlter S. Headache Characteristics in Chronic Neck Pain Patients with Loss of Cervical Lordosis: A Cross-Sectional Study Considering Cervicogenic Headache. Medical science monitor: international medical journal of experimental and clinical research. 2023;29:e939427-1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Shilton M, Branney J, de Vries BP, Breen AC. Does cervical lordosis change after spinal manipulation for non‑specific neck pain? A prospective cohort study. Chiropr Man Therap 2015;23:33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Liang G, Liang C, Zheng X, et al. Sagittal alignment outcomes in lordotic cervical spine: does three-level anterior cervical discectomy and fusion outperform laminoplasty? Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2019;44:E882-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Passias PG, Bortz C, Horn S, et al. Drivers of cervical deformity have a strong influence on achieving optimal radiographic and clinical outcomes at 1 year after cervical deformity surgery. World Neurosurg 2018;112:e61-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Lippa L, Lippa L, Cacciola F. Loss of cervical lordosis: what is the prognosis? Journal of Craniovertebral Junction and Spine. 2017 Jan 1;8(1):9-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]