To determine the prognostic factors and the recurrence risk related to aggressive surgical procedures for the management of GCT.

Dr. Yash Mehta, Department of Orthopaedics, New Civil Hospital, Surat, Gujarat, India. E-mail: yashmehtapanasonicp81@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a locally aggressive primary bone neoplasm constituted by proliferating mononuclear spindle cells, among which there are numerous macrophages and evenly distributed large multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells that may undergo malignant transformation. It corresponds to 5% of all primary neoplasias of the bone. It is more common in females, with an incidence between 20 and 45 years. It has a major preference for the epiphysis of the long bones. Approximately 3–4% of all GCTs are found in the small bones of the hands and feet. GCT in younger patients appears to occur in these locations more frequently than in long bones. GCT occurs more frequently in metatarsal bones than in other bones of feet. Involvement of the epiphysis is a rule, although in small bones, a significant portion of the shaft or even the entire bone can be involved. GCT of the acral skeleton shows more aggressive behavior than that of long tubular bones (higher recurrence rate, invasion) because of its location in small bones and difficulty in completely removing the tumor. Histologically benign lung metastases can occur.

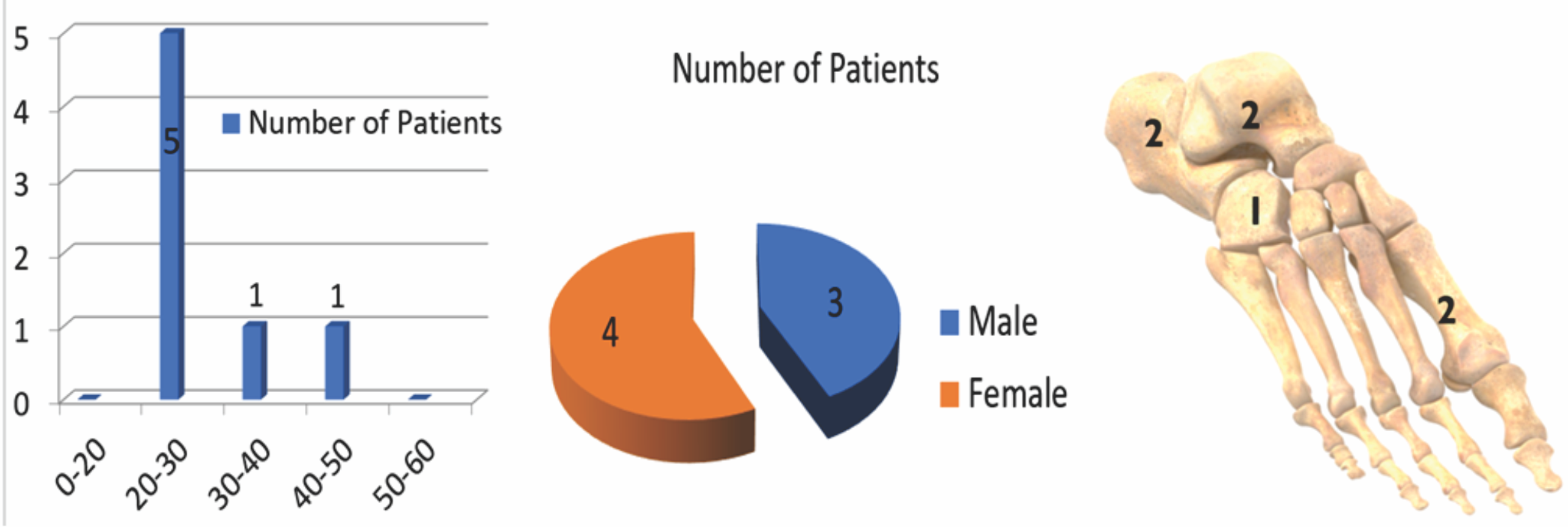

Methods and Materials: A prospective study was carried out in Surat, India, from 2018 to 2021, consisting of 7 patients. 6 cases were primary and 1 was recurrent. Campanacci Grade 1 for 2, Grade 2 for 2, Grade 3 for 3 patients. Operative procedures were extended curettage and adjuvants for 5, wide/marginal resection for 1, and ray amputation for 1. Musculoskeletal Tumor Society (MSTS) score was calculated for every patient.

Results: 71.42% patients belonged to the age group of 20–30 years. 71.42% patients presented in stages II and III. Good to excellent functional outcome (MSTS score) for 7 cases. 0 cases had local recurrence, and 0 had lung metastasis.

Conlusion: Primary GCT of small bones was found in the younger population and found to be biologically more aggressive than of long bones. Hence, the treatment of choice is extended curettage or wide/marginal resection. Adjuvant does not eliminate the risk of recurrence but possibly reduces its rate.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, Campanacci grade, extended curettage, marginal resection, musculoskeletal tumor society.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is often observed in long bones; however, our study focuses on a rarer site of the tumour in small bones of the foot. Small bone is a term coined for a bone that lies distal to the tibia and fibula in the foot.

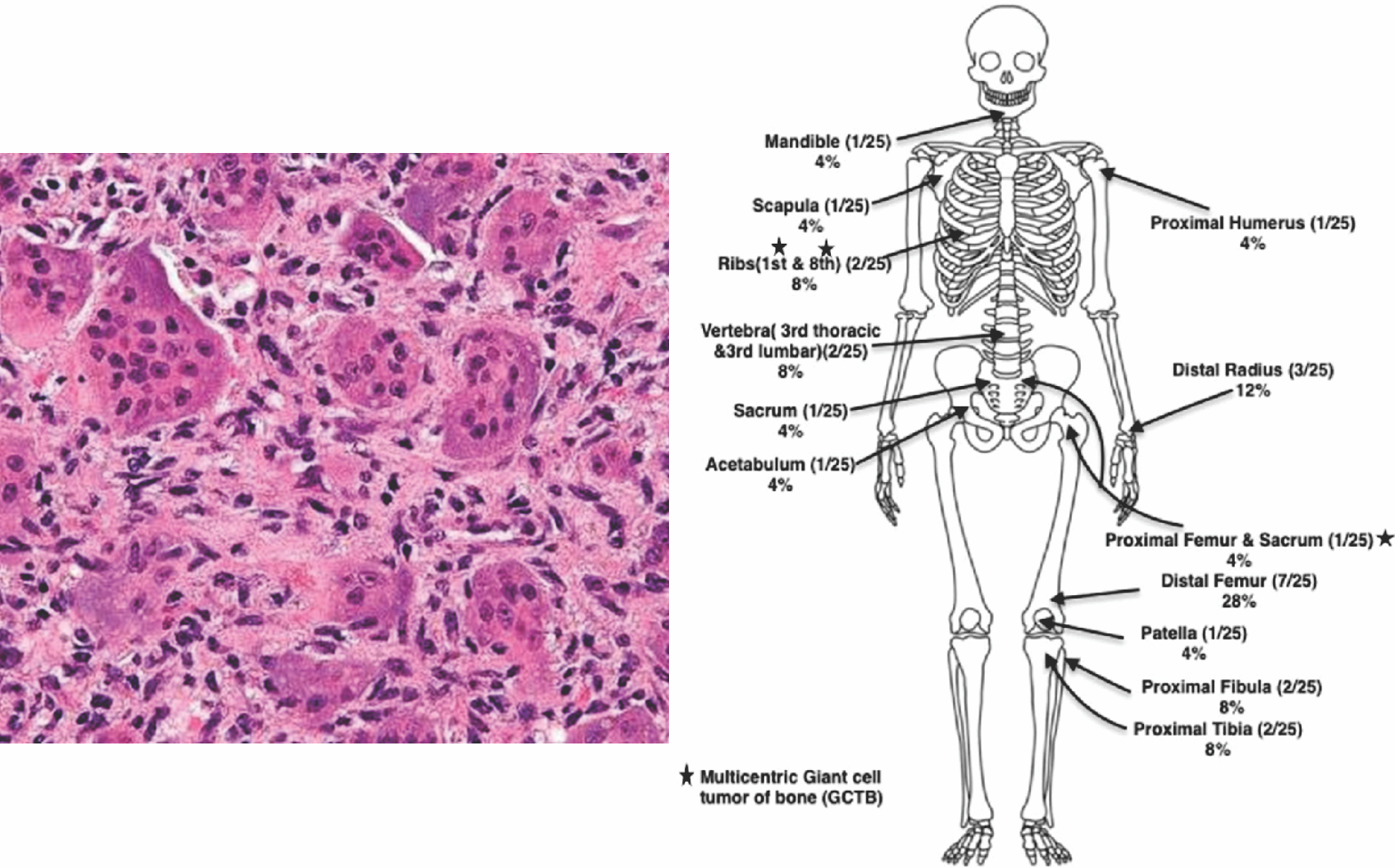

GCT of bone is locally aggressive, benign primary bone neoplasm constituted by proliferating mononuclear spindle cells. Along with these, there are numerous macrophages and evenly distributed large multinucleated osteoclast-like giant cells that may undergo malignant transformation (Fig. 1) [1].

Figure 1: Histopathological appearance of giant cell tumor and its distribution across all bones.

GCT corresponds to 5% of all primary neoplasias of the bone. It is more common in females, with an incidence between 20 and 45 years. It has a major preference for the meta-epiphysis of the long bones (Fig. 1) [2].

Approximately 3–4% of all GCTs are found in the small bones of the hands and feet. GCT occurs more frequently in metatarsal bones than in other bones of feet. Involvement of the Epiphysis is a rule, although in small bones, a significant portion of the shaft or even the entire bone can be involved. GCT of the Acral skeleton shows more aggressive behavior than of long tubular bones (higher recurrence rate, invasion) because of its location in small bones and difficulty in completely removing the tumor.

Due to the varying availability of surgical options and the possibility of revision surgical risk (due to high recurrence rate), GCT has always been the topic of controversy among surgeons, especially when it involves small bones of foot, where functional outcome preservation should NOT outweigh the risk of associated metastasis.

The purpose of this retrospective study was to determine (1) the prognostic factors and (2) the recurrence risk related to aggressive surgical procedures for the management of GCT.

A prospective study was carried out in Surat, India, from 2018 to 2021, consisting of 7 patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria of having a GCT in small bones of the hand and foot. All 7 patients were histopathologically confirmed to suffer from GCT of bone and were then included in the study. After institutional review board approval, a review of their medical details was conducted. This included:

- Age at presentation, sex

- Symptoms

- Disease location

- History of presentation

- Clinical findings

- Radiological findings

- Pathological findings.

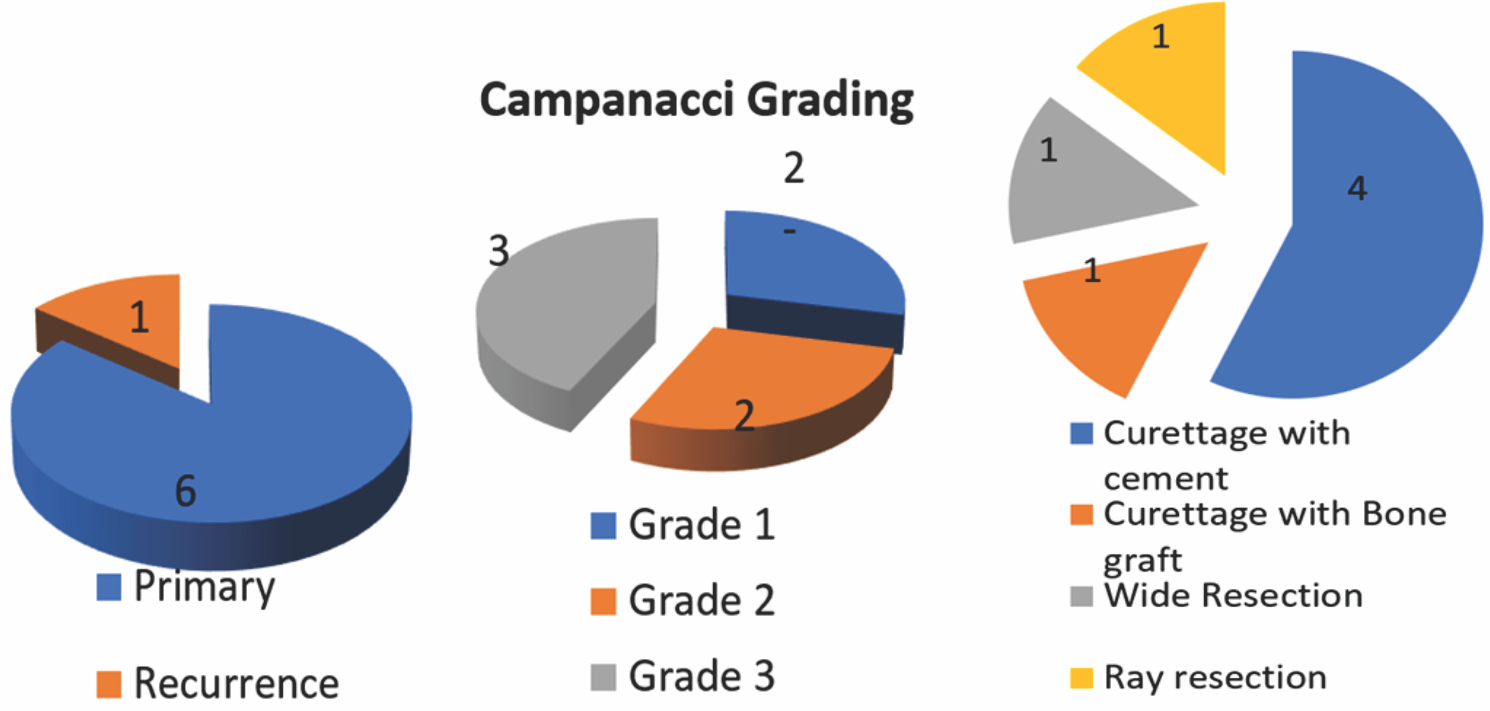

The Campanacci staging system was used to classify the GCT lesions based on their radiographic appearance, specifically focusing on the tumor’s aggressiveness and risk of local recurrence (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Campanacci staging system based on their radiographic appearance, specifically focusing on the tumor’s aggressiveness and risk of local recurrence.

- Grade 1 : Cystic intraosseous lesion, intact cortex

- Grade 2 : Expansile lytic lesion with thin cortex but NO break in cortex

- Grade 3 : Destructive radiolucent lesion with cortical break and soft tissue extension.

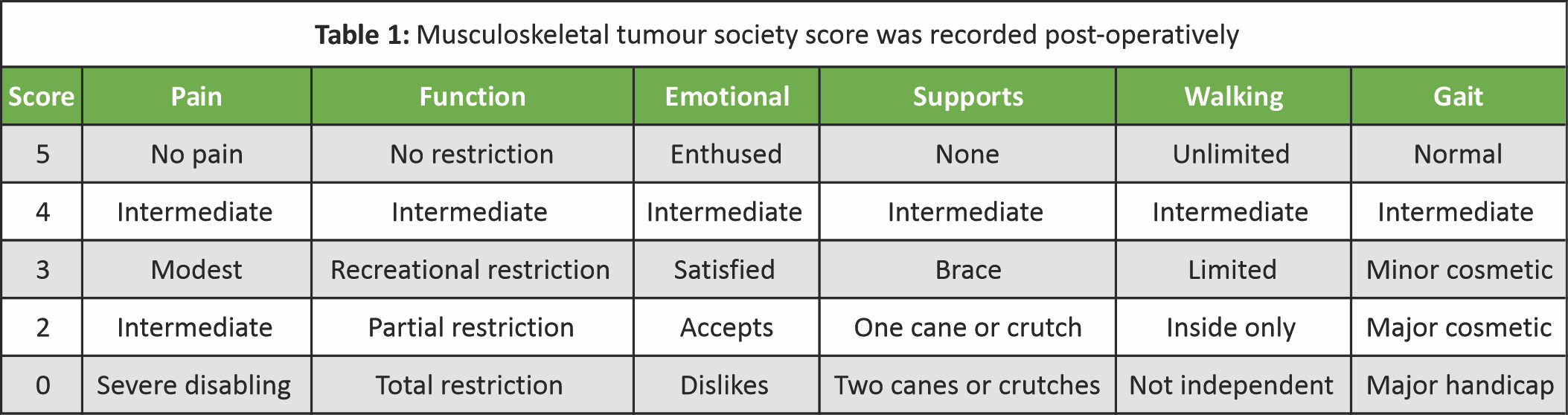

Musculoskeletal Tumour Society (MSTS) score was recorded postoperatively (Table 1).

On radiological evaluation, none of the patients showed any radiological sign of multicentric or metastatic GCT. All the patients were followed up for a mean duration of 2.8 years (6–48 months).

On radiological evaluation, none of the patients showed any radiological sign of multicentric or metastatic GCT. All the patients were followed up for a mean duration of 2.8 years (6–48 months).

Surgical techniques

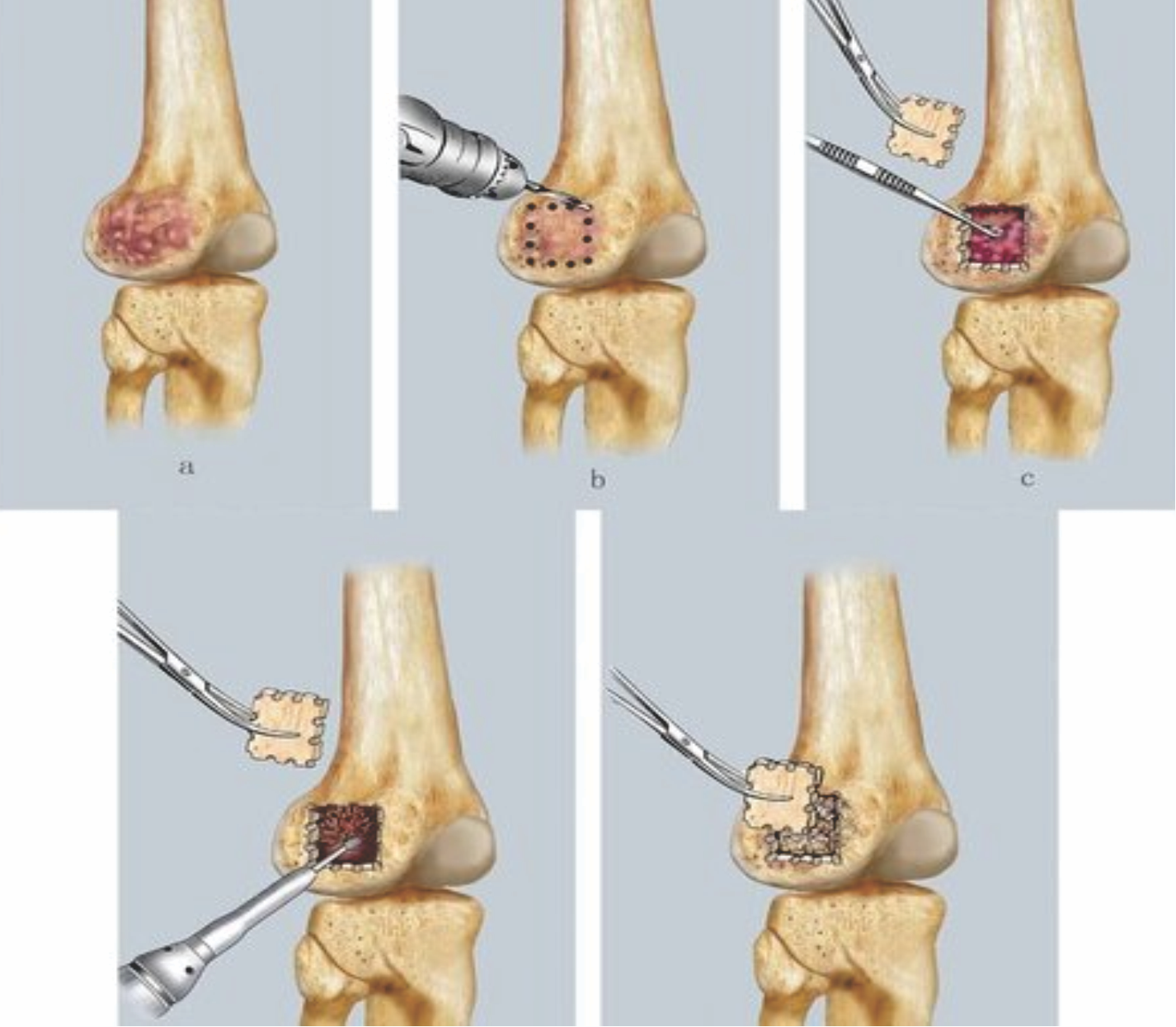

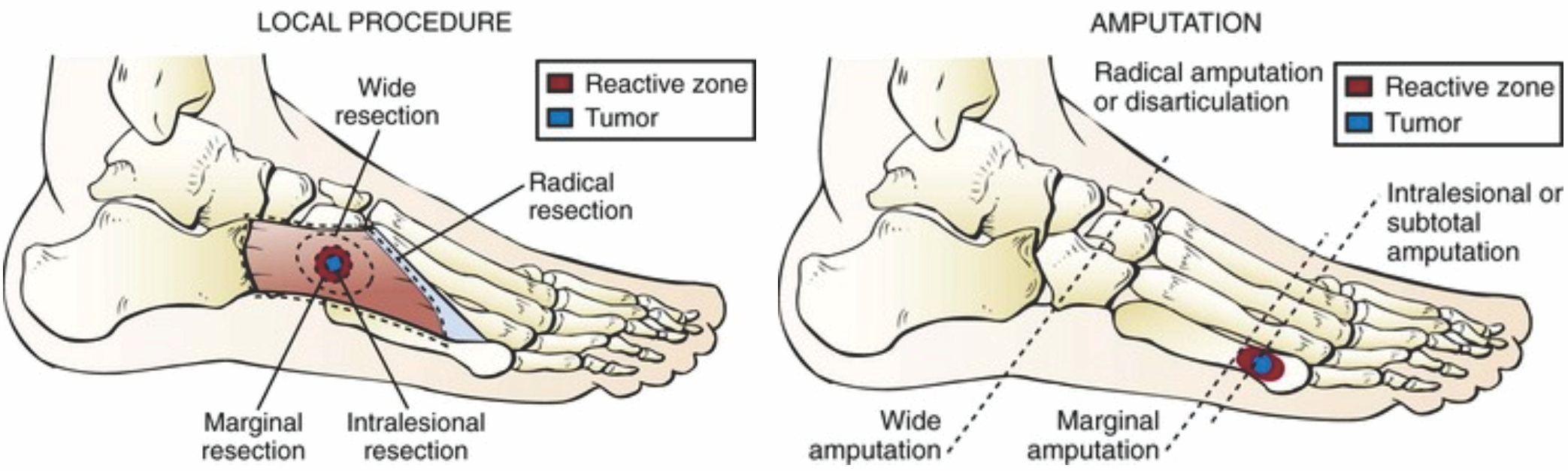

Various surgical techniques followed for GCT have been local procedures, such as wide resection, marginal resection (Fig. 3 and 4), and radical procedures, such as ray amputation, disarticulation (Fig. 4) [3].

Figure 3: Bone currettage followed by cementing or bone grafting has been the most commonly practiced technique for giant cell tumor.

Of all surgical techniques, bone curettage followed by cementing or bone grafting has been the most commonly practiced technique for GCT (Fig. 3). This technique involves raising a cortical osseous flap of affected bone. Then extended curettage of the lesion is done with a high-speed burr device, and phenol is used as an adjuvant. Electrocautery is used at margins for neutralizing marginal tumor cells. Finally, the lesion is filled with polymethyl methacrylate cement or bone graft. Ultimately, the defect was closed with the same osseous flap.

Figure 4: Local procedures like wide resection, marginal resection. Radical procedures like ray amputation, disarticulation.

5 out of 7 patients belonged to the young age group of 20–30 years with a male-to-female ratio of 3:4. Out of 7 patients, 2 presented with GCT of calcaneum, Talus, and 1st metatarsal each, whereas 1 presented with GCT of cuboid bone (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Age, sex distribution of patients and location of tumor in foot bones.

Out of 7 total cases, 6 cases were primary and 1 was recurrent (Fig. 6). Local recurrence of GCT was observed in the calcaneum at the previously operated site (in other hospital). As per the grading, there was Campanacci Grade 1 for 2 patients, Grade 2 for 2 patients and Grade 3 for 3 patients (Fig. 6). Out of 7 patients, 4 underwent curettage with cementing, 1 each underwent curettage with bone grafting, wide/marginal resection, and ray resection (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Primary tumor versus recurrence distribution, campanacci grading for giant cell tumor and the surgical techinque in the 7 patients.

On review of MSTS score recorded postoperatively, all 7 patients showed good to excellent functional outcome. NO patients had any new local recurrence. NO patients had lung metastasis.

Table 2 elaborates on age, sex, bone involved, and the surgical treatment done for all the 7 cases.

Some cases

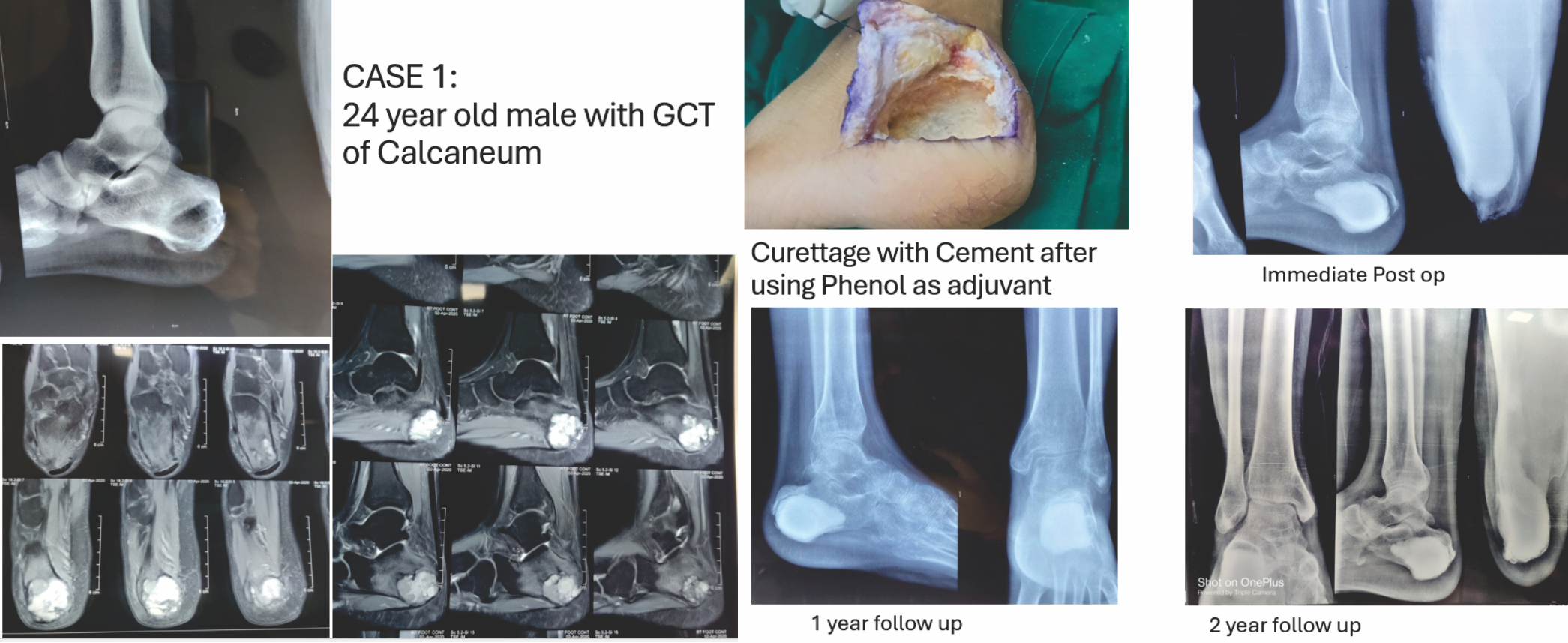

First case

GCT of calcaneum in 24-year-old male treated by Curettage and cementing after using Phenol as an adjuvant. X-rays showing follow-up at 1 and 2 years (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Giant cell tumor of calcaneum in 24 year old male treated with curettage with cementing.

Second case

GCT of 1st Metatarsal in 24-year-old male treated by marginal resection followed by fibula grafting. X-rays showing immediate follow-up (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: Giant cell tumor of 1st metatarsal in 24 year old male treated with marginal resection followed by fibula grafting.

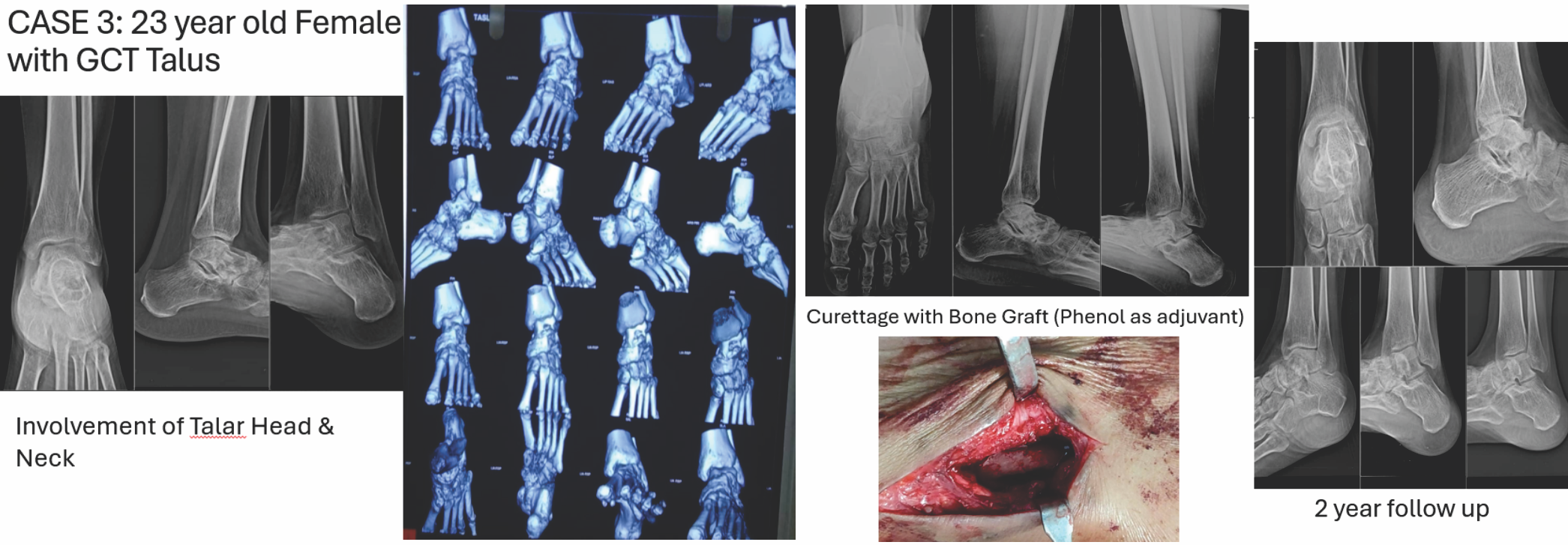

Third case

GCT of the Talar head and neck in 23-year-old female treated by curettage and bone grafting after using phenol as an adjuvant. X-rays showing follow-up at 2 years (Fig. 9).

Figure 9: Giant cell tumor of talus in 23 year old female treated with curettage and bone grafting.

GCT is a primary bone tumor, 85% of which is found in long bones of the body and 10% in the axial skeleton, whereas the small bones of the hand and foot are found to be rarely involved [4]. GCT of small bones is asymptomatic during the early stages. Due to its multidirectional expansion, the tumor involves the cortex and surrounding soft tissues rapidly, thereby presenting in late stages. The incidence of GCT is higher in Asian populations, with the highest reported incidence being in South India (30.3%) [5]. Most GCTs are present between the age of 30 and 50 years. However, GCT of small bones presents earlier, mainly in the 20 s, which was observed by different studies on small bones affected by GCT [6-8].

In our study, 5 out of 7 patients (71.42%) belonged to the age group of 20–30 years. A total of 71.42% (5 out of 7) of our patients presented in stages II and III. In a study of 18 subjects conducted by Rajani et al. [9] on GCT of the foot and ankle, similar findings were concluded. Only 10% of their patients presented in stage I. As a result of its late-stage presentation, major bony destruction and diaphyseal, as well as surrounding tissue extension, are seen, and this limits its surgical options. In accordance with other similar studies, GCT in the small bones of the foot was found to be less aggressive in comparison to other bony lesions of GCT [10,11].

Recurrence of GCT in small bones is a major complication affecting both the operating surgeon and the patient. In the preceding studies, the recurrence rate of GCT in small bones has ranged from 25% to 50% [4,6,8,9]. Biscaglia et al. [8] studied 29 cases of GCT of the hand and foot and found a recurrence rate of 30% in their patients. This suggested highly aggressive nature of GCT in small bones. Averill et al. [12] conducted a multi-institutional study on 21 patients and 28 lesions. The local recurrence amounted to 90% with curettage or curettage and bone grafting. In another study by Athanasian et al. [13] on 14 patients, 79% accounted for recurrence whose primary lesion was treated with curettage. However, these studies lacked the use of any neoadjuvant.

The case of recurrence of GCT in the calcaneum that we faced in our study was treated with extended curettage and cementing. Rajani et al. [9] also advocated the use of adjuvants in their study and recommended not to use curettage or bone grafting alone. Different agents used as adjuvants are: Phenol, hydrogen peroxide, high-speed burr, pulse lavage, and surface Cauterisation. However, due to cost-efficiency in India, the use of such agents is currently very limited. Apart from phenol, hydrogen peroxide is also readily available and cost-effective, and thus can be used as an efficient adjuvant. Omlor et al. [14] commented on the efficacy of hydrogen peroxide use locally to clean the cavity and drew the inference that hydrogen peroxide increased the recurrence-free survival rate. In our study, there was NO single case of recurrence, though. But we had operated upon a case of recurrent GCT in calcaneum. Our current study used phenol as an adjuvant, and no patient presented with recurrence, which could be the reason behind the lower recurrence rate.

Primary GCT of small bones was found in the younger population (the 20 s) and found to be biologically more aggressive than of long bones. Hence, the treatment of choice is extended curettage or wide/marginal resection. The use of adjuvants does not eliminate the risk of recurrence but possibly reduces its rates. Surgeons must strike a balance between the functional outcome of the chosen method and the risk of its recurrence while operating on these fairly young patients.

Extended curettage or wide/marginal resection is the surgical treatment of choice for GCT, which is more aggressive in small bones of foot : Appearance at an early age, presenting at later stages with a high rate of recurrence. Use of an adjuvant reduces the risk of recurrence.

References

- 1. Vaishya R, Kapoor C, Golwala P, Agarwal AK, Vijay V. A rare giant cell tumor of the distal fibula and its management. Cureus 2016;8:e666. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Mohaidat ZM, Al-Jamal HZ, Bany-Khalaf AM, Radaideh AM, Audat ZA. Giant cell tumor of bone: Unusual features of a rare tumor. Rare Tumors 2019;11:2036361319878894. doi: 10.1177/2036361319878894. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 3. Calvert GT, Lor Randall R. Musculoskeletal key. In: Soft Tissue and Bone Tumors. Ch. 18. France: International Agency for Research on Cancer; 2024. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Oliveira VC, Van Der Heijden L, Van Der Geest IC, Campanacci DA, Gibbons CL, Van De Sande MA, et al. Giant cell tumours of the small bones of the hands and feet: Long-term results of 30 patients and a systematic literature review. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:838-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Reddy CR, Rao PS, Rajakumari K. Giant-cell tumors of bone in South India. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:617-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Yanagisawa M, Okada K, Tajino T, Torigoe T, Kawai A, Nishida J. A clinicopathological study of giant cell tumor of small bones. Ups J Med Sci 2011;116:265-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Co HL, Wang EH. Giant cell tumor of the small bones of the foot. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2018;26:2309499018801168. doi: 10.1177/2309499018801168. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 8. Biscaglia R, Bacchini P, Bertoni F. Giant cell tumor of the bones of the hand and foot. Cancer 2000;88:2022-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Rajani R, Schaefer L, Scarborough MT, Gibbs CP. Giant cell tumors of the foot and ankle bones: High recurrence rates after surgical treatment. J Foot Ankle Surg 2015;54:1141-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Malawer MM, Vance R. Giant cell tumor and aneurysmal bone cyst of the talus: Clinicopathological review and two case reports. Foot Ankle 1981;1:235-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. O’Keefe RJ, O’Donnell RJ, Temple HT, Scully SP, Mankin HJ. Giant cell tumor of bone in the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 1995;16:617-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Averill RM, Smith RJ, Campbell CJ. Giant-cell tumors of the bones of the hand. J Hand Surg Am 1980;5:39-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Athanasian EA, Wold LE, Amadio PC. Giant cell tumors of the bones of the hand. J Hand Surg Am 1997;22:91-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Omlor GW, Lange J, Streit M, Gantz S, Merle C, Germann T, et al. Retrospective analysis of 51 intralesionally treated cases with progressed giant cell tumor of the bone: Local adjuvant use of hydrogen peroxide reduces the risk for tumor recurrence. World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]