Neglected Monteggia Fracture-Dislocations with PIN Palsy (arriving after 1 month) can be successfully managed with appropriate surgical intervention without the need of Posterior Interosseous Nerve exploration.

Dr. Priti Ranjan Sinha, Department of Orthopaedics, Teerthanker Mahaveer Medical College and Research Centre, Moradabad, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: drpritiranjansinha@gmail.com

Introduction: Monteggia fracture-dislocations are rare in children can often go undiagnosed, especially when initial treatment is provided by non-specialists. Missed injuries can result in chronic instability, pain, and limited function of the elbow joint.

Case Report: We report the case of an 8-year-old girl who sustained an injury to her left elbow after falling while escaping a monkey attack. She initially received only bandaging from a local practitioner and presented to us 1 month later with ongoing pain and restricted elbow movement with posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) palsy. Radiographs revealed a neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocation. She was treated surgically with ulnar osteotomy and fixation with a 3.5 mm dynamic compression plate without reduction of the Radial head. The radial head was found to be reduced after ulnar osteotomy and plate fixation. PIN was not explored. Over a 15-month follow-up, the fracture united well, the radial head remained anatomically positioned, and the patient regained a full range of motion without pain with complete recovery of PIN palsy.

Conclusion: This case highlights the potential for Monteggia lesions to be overlooked when not properly assessed at the time of injury. It underscores the importance of early diagnosis and appropriate orthopedic intervention to prevent long-term complications. Even in delayed cases, satisfactory outcomes can be achieved with timely surgical management.

Keywords: Neglected Monteggia fracture, BADO type 1, posterior interosseous nerve palsy, ulnar osteotomy, plating, radial head dislocation.

Monteggia fracture-dislocations are characterized by a fracture of the proximal ulna accompanied by dislocation of the radial head at the elbow [1]. These injuries are relatively uncommon in the pediatric population, accounting for <1% of all forearm fractures in children. Despite their rarity, timely recognition and management are crucial for preventing long-term functional impairment [2].

In children, the clinical presentation can be subtle, and the radial head dislocation may be easily overlooked, particularly if attention is focused solely on the ulnar fracture. Inadequate initial assessment, especially in settings where radiographs are not obtained or interpreted correctly, can result in missed or delayed diagnosis [3]. A neglected Monteggia lesion – defined as one that remains untreated for more than 4 weeks – can lead to chronic pain, limited range of motion, deformity, and joint instability if not properly addressed [4].

The mechanism of injury in Monteggia fractures typically involves a fall on an outstretched hand with the forearm in hyperpronation or hyperextension [5]. However, unusual circumstances, such as animal attacks or falls in panic, can also result in such injuries, as seen in this case. Incidence of posterior interosseous nerve (PIN) palsy is 3–31% and is commonly associated with Type 3 BADO. Here we report a rare case of PIN palsy in BADO Type 1 [6].

This case report discusses a unique presentation of a neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocation in an 8-year-old girl who sustained the injury while riding a bicycle and was attacked by a monkey, leading to a fall from the vehicle on an outstretched hand. The unusual mechanism, delayed presentation, and successful surgical management underscore the importance of clinical vigilance and appropriate intervention in pediatric trauma cases.

An 8-year-old previously healthy girl presented to our orthopedic outpatient clinic with complaints of persistent pain, swelling, and limited movement in her left elbow. The symptoms had been on-going for approximately 1 month following a fall. According to the parents, the child was running away from a monkey attack when she tripped and fell directly onto her outstretched left arm.

Immediately following the injury, she experienced pain and swelling around her left elbow. She was taken to a local practitioner, who provided conservative management in the form of a tight bandage and advised rest. No radiological investigation was performed at that time. The symptoms did not resolve over the subsequent weeks, and the child continued to experience discomfort, visible deformity, and difficulty in using her left upper limb for daily activities. Concerned about the lack of improvement, her parents brought her to our facility for further evaluation.

On clinical examination, there was visible swelling and mild deformity over the lateral aspect of the left elbow. Tenderness was elicited over the proximal ulna, and the radial head appeared prominent anteriorly. The elbow had a restricted range of motion, especially in flexion and supination, both of which were painful. Neurological examination of the left upper limb revealed weakness in the Metacarpophalangeal joint (MCP) and thumb extension, suggestive of PIN palsy. Distal vascularity was intact.

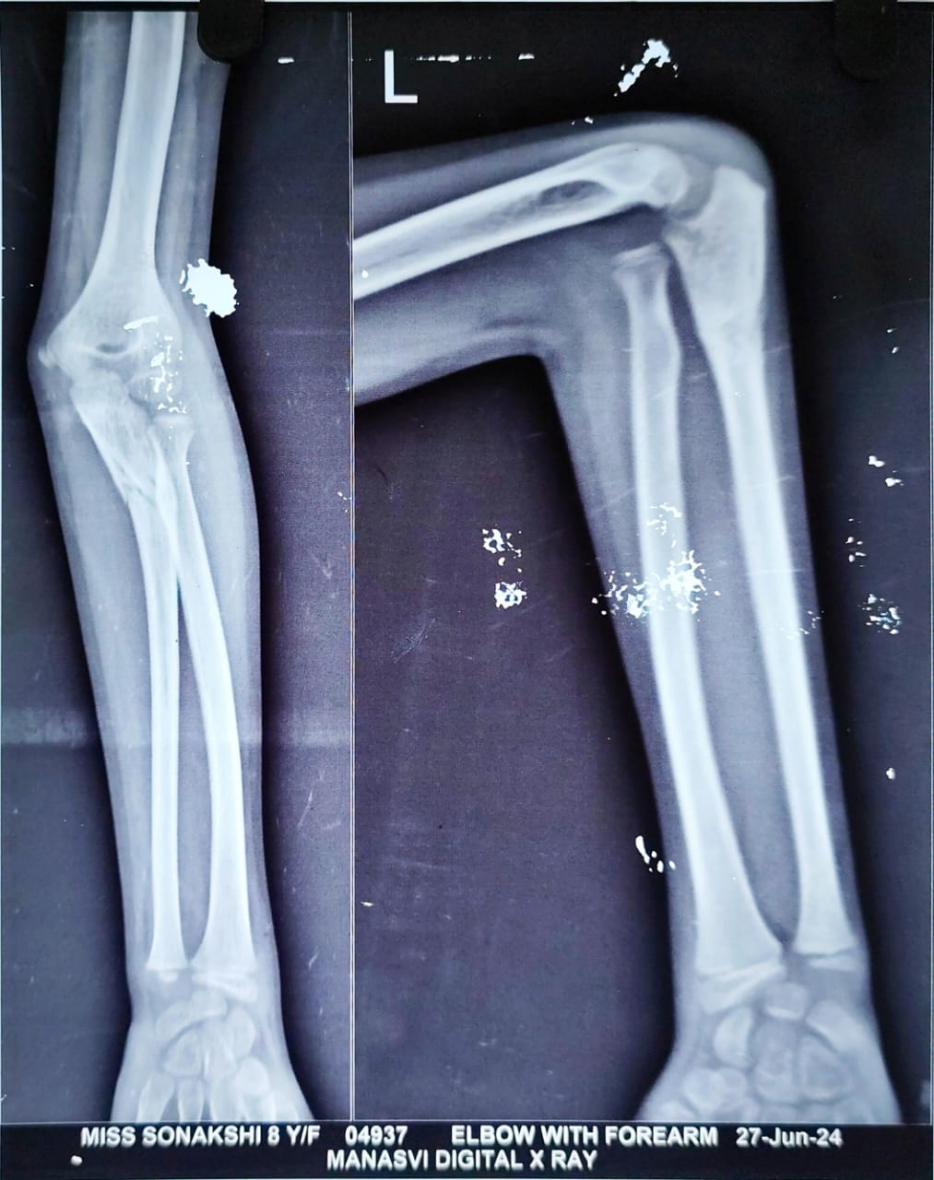

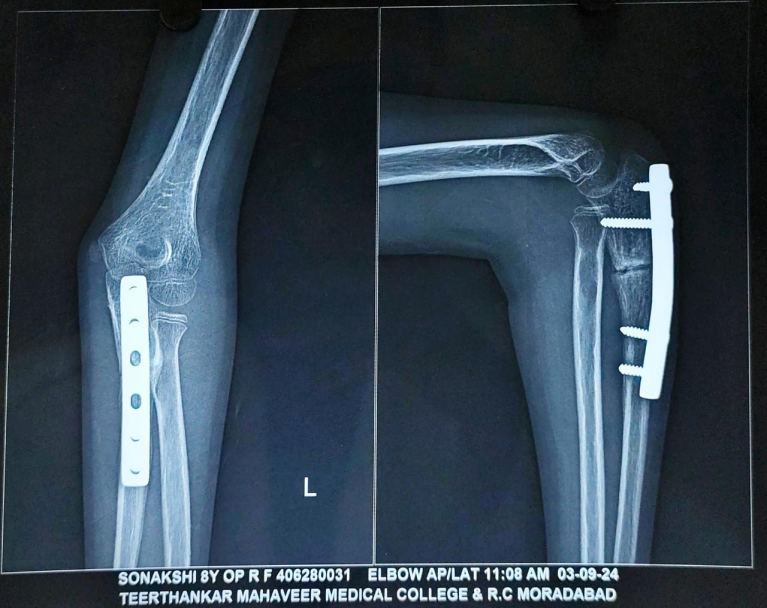

Radiographs of the left forearm and elbow (anteroposterior and lateral views) revealed a uniting fracture of the proximal ulna with anterior dislocation of the radial head (Fig. 1) – findings consistent with a Bado type I Monteggia lesion. Given the history of trauma, absence of early imaging, and delayed presentation, a diagnosis of neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocation was made. Advanced imaging was not done as the radiographs were indicative of a Monteggia lesion in a 1-month-old injury. Radiographs were analyzed by methods as described by Lincoln and Mubarak, including the ulnar bow sign and the radiocapitellar line of McLaughlin [7].

Figure 1: Monteggia fracture dislocation left elbow (1-month-old).

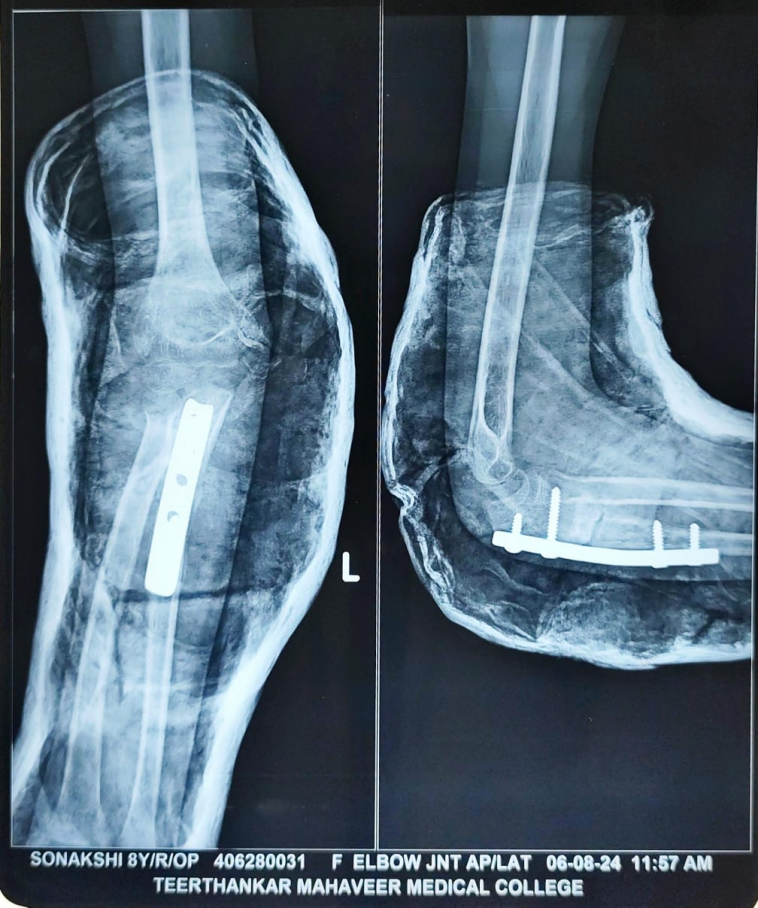

Surgical intervention was planned to restore normal elbow anatomy and function. Under general anesthesia and with tourniquet control, the child underwent open reduction and internal fixation of the ulna with distraction angulation ulnar osteotomy to correct the angulation and length. Across a Boyd approach (Fig. 2), an overcontoured AO 3.5 mm small fragment DCP was used to stabilize the ulnar osteotomy and to ensure proper alignment through which the radial head reduced spontaneously (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Boyd approach showing the fracture site.

Figure 3: Immediate post-operative X-ray showing reduced radial head with ulnar osteotomy site fixed with AO 3.5 mm small fragment DCP plate.

No open reduction of the radial head was required. Radial head relocation, as well as stability of the radial head, was confirmed intra-operatively. The PIN was not surgically explored in this case, as most nerve injuries associated with Monteggia fractures are neuropraxia and tend to recover spontaneously without the need for intra-operative nerve exploration [8]. In the treatment of Monteggia fractures, plating plays a better role than intramedullary nailing as it provides rigid fixation, allows restoration of ulnar length, and facilitates accurate angulation correction, which is essential for maintaining stable reduction of the radial head [9].

The post-operative course was uneventful. The limb was immobilized in an above-elbow slab for 3 weeks, followed by initiation of a gentle range of motion exercises under physiotherapy guidance. The child was monitored at regular intervals – 2 weeks, 1 month, 3 months, 6 months, 9 months, and 15 months post-operatively (Fig. 4, 5, 6, 7).

Figure 4: 1-month follow-up X-ray.

Figure 5: 3-month follow-up.

Figure 6: 6-month follow-up.

Figure 7: 9-month follow-up.

At each visit, clinical and radiographic assessments were performed. Over time, the child regained the movement in the wrist and MCP joint extension and thumb extension.

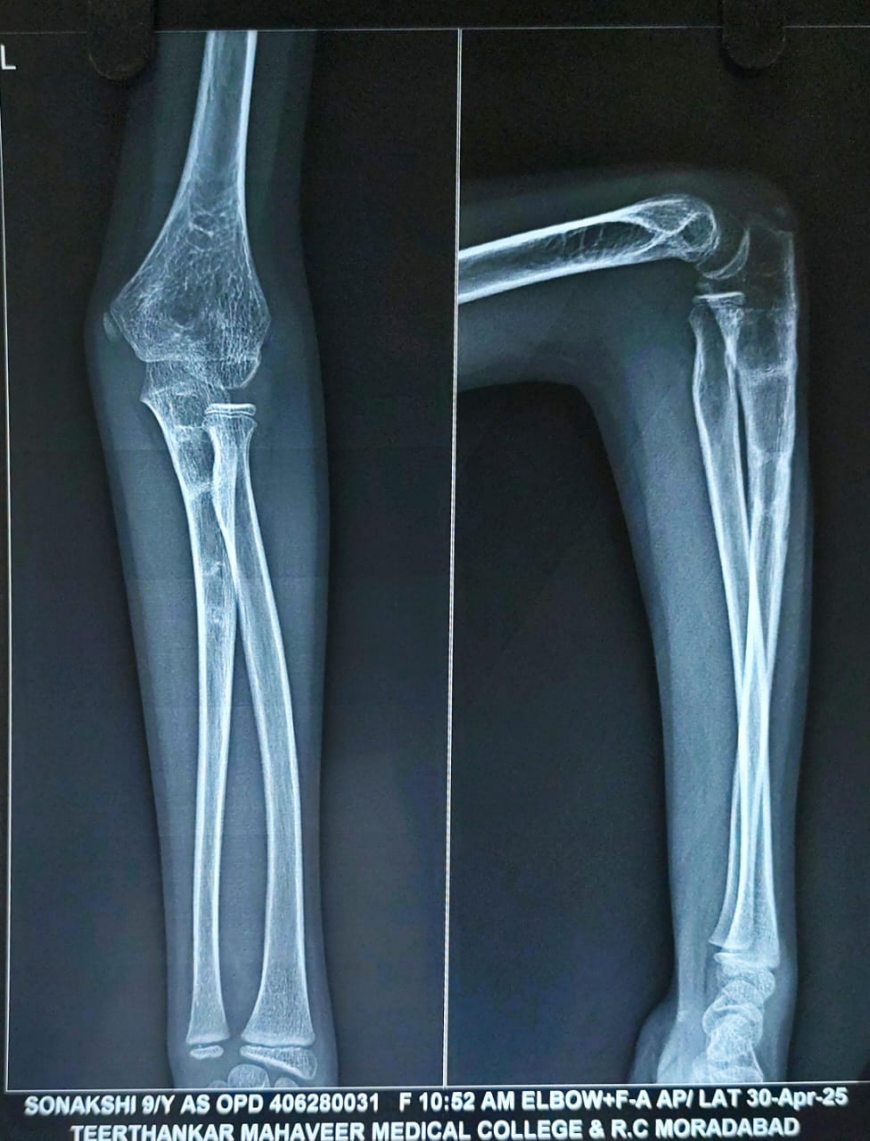

By the 9-month follow-up, radiographs confirmed complete union of the osteotomized ulna, and the radial head remained in a reduced, anatomical position. To prevent any implant-related complications, implant removal was done at 9 months (Fig. 8).

Figure 8: X-ray after implant removal.

At the time of the past follow-up at 15 months, the X-ray demonstrated a well-maintained reduction of the radial head with congruent radiocapitellar alignment. The ulna showed complete union with satisfactory remodeling. There was no evidence of implant-related complications, re-dislocation, or deformity (Fig. 9). The child had regained a full, pain-free range of motion in the left elbow, including full flexion, extension, pronation, and supination (Fig. 10a, b, c, d). There were no signs of instability or functional limitations in daily activities. Almost complete recovery of PIN palsy was obtained. At the 15-month follow-up, physeal growth disturbance and angular deformities were evaluated and not observed. The patient achieved an excellent outcome as per the Mayo Elbow performance score.

Figure 9: Follow-up radiograph at 15 months after surgery. The image shows maintained reduction of the radial head with congruent radiocapitellar alignment, complete union and remodelling of the ulna, and absence of implant-related complications or re-dislocation.

Figure 10: (a, b, c, d) Showing complete range of motion in the post-operative period after 15 months.

This case highlights the successful management of a delayed Monteggia lesion (after 1 month) using corrective ulnar osteotomy without radial head reduction, emphasizing the potential for excellent outcomes even in late presentations when appropriate surgical intervention is performed.

Monteggia fracture-dislocations are infrequent but clinically significant injuries in the pediatric population. First described by Giovanni Battista Monteggia in 1814 and later classified by Bado in 1967, these injuries involve a fracture of the proximal or midshaft ulna accompanied by dislocation of the radial head. Among children, Bado type I lesions, characterized by anterior dislocation of the radial head with an anterior angulated ulnar fracture, are the most common [1].

These injuries are often missed at initial presentation, especially in settings where radiographs are not routinely obtained or are inadequately interpreted. Misdiagnosis may occur in up to 50% of cases during initial evaluation, particularly when clinical signs are subtle and only the forearm or wrist is imaged [7]. The lack of suspicion and awareness among non-orthopedic healthcare providers further contributes to delayed diagnosis, as seen in our case, where the child received only bandaging without imaging or referral.

The consequences of a missed Monteggia fracture-dislocation can be substantial. Chronic radial head dislocation may result in pain, decreased range of motion, cubitus valgus deformity, ulnar nerve palsy, and long-term joint degeneration if not addressed [3,10]. In children, the remodeling potential of bones is high, but spontaneous reduction of a chronically dislocated radial head is unlikely beyond a few weeks post-injury.

In neglected Monteggia lesions, surgical management is typically required to restore elbow alignment and function. The cornerstone of treatment involves ulnar osteotomy, which re-establishes the correct length and alignment of the ulna, thereby facilitating spontaneous or assisted reduction of the radial head. This approach is often sufficient without the need to reduce the radial head directly [11]. In our patient, osteotomy and internal fixation of the ulna enabled successful reduction of the radial head, which remained stable throughout follow-up.

Timing plays a critical role in outcomes. Several studies have reported satisfactory results even when surgery is performed several months after the initial injury, provided that the radial head is reducible and there is no significant secondary degenerative change [12,13,14]. In our case, the surgical intervention at 1-month post-injury led to full restoration of elbow motion and anatomic alignment, emphasizing the potential for good outcomes even in delayed presentations.

This case is notable not only due to the delay in diagnosis but also the unusual mechanism of injury – a fall while escaping a monkey attack. Such atypical causes highlight the importance of thorough clinical evaluation in pediatric trauma, regardless of the initial presentation or context. Moreover, the case underscores the need for education and training among general practitioners, emergency physicians, and rural healthcare providers in recognizing early signs of pediatric elbow injuries and ensuring appropriate referral.

Overall, this case contributes to the existing literature by reinforcing that early recognition, imaging, and timely surgical correction are vital in managing Monteggia injuries. Even in delayed cases, surgical correction can yield excellent anatomical and functional results.

Limitations of the case report

The present report highlights the management of a single pediatric patient with a neglected Monteggia lesion. As such, the findings cannot be extrapolated to the broader pediatric population. The absence of a control group or comparison with other surgical options limits the ability to comment on the relative superiority of the chosen technique. Furthermore, as with all case reports, there is an inherent risk of selection and reporting bias, since successful outcomes are more likely to be published than unfavorable ones.

Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children require a high index of suspicion for timely diagnosis. Due to the rarity and subtle clinical presentation, especially in young children, these injuries are prone to being overlooked – particularly when initial treatment is sought from non-specialist or rural practitioners without access to proper imaging. If missed, they can lead to chronic radial head dislocation, persistent pain, limited elbow motion, and long-term disability.

This case highlights several critical learning points. First, it demonstrates the importance of thorough clinical evaluation and radiographic imaging of the entire forearm, including the elbow joint, in all pediatric upper limb injuries. Second, it underscores that even in neglected cases, favorable outcomes are possible with timely surgical intervention. In this child, successful open reduction, internal fixation with ulnar osteotomy, and realignment of the radial head resulted in full recovery of elbow function, despite the delay in presentation.

Furthermore, the unusual mechanism of injury – falling while fleeing from a monkey attack – adds to the uniqueness of this case. It serves as a reminder that clinicians should maintain diagnostic vigilance regardless of how unusual or trivial the mechanism of injury may appear.

Finally, this report emphasizes the need for improved awareness and education among frontline healthcare providers about pediatric elbow injuries. Prompt referral, early diagnosis, and appropriate orthopedic intervention remain the cornerstones of successful outcomes in Monteggia lesions. With correct surgical planning and follow-up, even delayed presentations can result in excellent anatomical and functional restoration in children.

Neglected Monteggia fracture-dislocations after 1 month can be successfully managed with ulnar osteotomy, plating without the need for exploration of PIN.

References

- 1. Bado JL. The monteggia lesion. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1967;50:71-86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Wiley JJ, Galey JP. Monteggia injuries in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1985;67:728-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ramski DE, Hennrikus WP, Bae DS, Baldwin KD, Patel NM, Waters PM, et al. Pediatric monteggia fractures: A multicenter examination of treatment strategy and early clinical and radiographic results. J Pediatr Orthop 2015;35:115-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Garg P, Kothari A, Gupta S, Srivastava A. Outcome of radial head preserving operations in missed Monteggia fractures. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:396-400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Gleeson AP, Beattie TF. Monteggia fracture-dislocation in children. J Accid Emerg Med 1994;11:192-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Macedo F, Rocha M, Lucas J, Rodrigues LF, Varanda P, Ribeiro E. Tardy posterior interosseous nerve palsy as a complication of unreduced Monteggia fracture: A case report and literature review. J Orthop Case Rep 2025;15:107-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Lincoln TL, Mubarak SJ. “Isolated” traumatic radial-head dislocation. J Pediatr Orthop 1994;14:454-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Demirel M, Sağlam Y, Tunalı O. Posterior interosseous nerve palsy associated with neglected pediatric Monteggia fracture-dislocation: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2016;27:102-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Shrestha D, Acharya BM, Mishra SR. Monteggia fracture-dislocation: Analysis of outcome in adults. Kathmandu Univ Med J (KUMJ) 2006;4:345-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Ring D, Waters PM. Operative fixation of Monteggia fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1996;78:734-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Olney BW, Menelaus MB. Monteggia and equivalent lesions in childhood. J Pediatr Orthop 1989;9:219-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Hirayama T, Takemitsu Y, Yagihara K, Mikita A. Operation for chronic dislocation of the radial head in children. Reduction by osteotomy of the ulna. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1987;69:639-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Gubaeva AR, Zorin VI. Missed Monteggia fractures in children – the current state of the problem: A systematic review. Pediatr Traumatol Orthop Reconstr Surg 2023;11:81-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Nakamura K, Hirachi K, Uchiyama S, Takahara M, Minami A, Imaeda T, et al. Long-term clinical and radiographic outcomes after open reduction for missed Monteggia fracture-dislocations in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2009;91:1394-404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]