Large isolated synovial chondromatosis of the posterior knee can be safely excised via a posteromedial tibial approach and protects neurovascular structures.

Dr. Ravipati Aakash, Postgraduate Resident, Department of Orthopaedics, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences. Bhubaneswar, India. Email: Aakashravipati3@gmail.com

Introduction: Synovial chondromatosis is a rare, benign metaplastic disorder of the synovium characterized by the formation of multiple cartilaginous nodules within the joint. While the knee is the most frequently affected site, isolated posterior compartment involvement is uncommon, and massive lesions in this location are particularly rare. The anatomical complexity of the popliteal region, with its proximity to critical neurovascular structures, presents unique surgical challenges. Arthroscopic removal is often inadequate for large, posteriorly located lesions due to restricted access and visualization.

Case Report: We report the case of a patient with massive synovial chondromatosis localized to the posterior compartment of the knee, presenting with progressive pain, swelling, and restricted motion. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a lobulated, multi-nodular synovial mass closely related to the popliteal neurovascular bundle. Considering the lesion size, posterior localization, and the need for complete excision, a posterior open synovectomy was performed. Through a posteromedial approach, the neurovascular structures were identified and protected, allowing en bloc removal of a large number of cartilaginous nodules along with affected synovium. Histopathology confirmed benign synovial chondromatosis. Post-operative recovery was uneventful, with restoration of the full range of motion and no recurrence at 1-year follow-up.

Conclusion: This case demonstrates that in massive posterior compartment synovial chondromatosis, a posterior open approach provides superior exposure, facilitates safe neurovascular preservation, and enables complete removal of large lesions, thereby reducing recurrence risk. Early recognition of posterior localization through MRI and tailoring the surgical approach to lesion size and extent are critical for optimal outcomes.

Keywords: Posterior knee approach, synovial chondromatosis, open synovectomy.

Synovial chondromatosis is an uncommon, benign metaplastic disorder of the synovium, characterized by the formation of multiple cartilaginous nodules within the synovial membrane of joints, bursae, or tendon sheaths. These nodules may remain attached to the synovium or detach as loose bodies within the joint cavity. The pathophysiology involves cartilaginous metaplasia of the synovial membrane, where synoviocytes transform into chondrocytes, producing hyaline cartilage. Over time, these nodules may calcify or ossify, resulting in mixed radiological appearances [1]. The disease typically progresses through three stages: An initial phase of active synovitis without loose bodies, a transitional phase with both synovitis and non-calcified loose bodies, and a late phase in which synovitis subsides but multiple calcified loose bodies remain. While the exact etiology remains unclear, proposed mechanisms include trauma, chronic mechanical irritation, and genetic predisposition, though most cases are idiopathic [2]. Epidemiologically, synovial chondromatosis is rare, with an estimated incidence of approximately 1/100,000 individuals. It demonstrates a male predominance, with a male-to-female ratio of about 2:1, and most often presents between the third and fifth decades of life. Although it can occur in any synovial joint, large joints such as the knee are most commonly affected, followed by the hip, elbow, shoulder, and ankle. Extra-articular involvement of bursae and tendon sheaths is rare, and isolated disease confined to the posterior compartment of the knee is particularly uncommon. Most cases are monoarticular, and bilateral disease is exceptionally rare [3]. Clinically, patients present with an insidious onset of pain, swelling, stiffness, and restricted range of motion. Mechanical symptoms such as locking, clicking, or a sensation of instability may occur due to intra-articular loose bodies. On examination, diffuse swelling, palpable nodules, or localized tenderness may be detected, and movement is often limited by pain or mechanical obstruction. If left untreated, synovial chondromatosis can cause progressive cartilage damage, secondary osteoarthritis, chronic pain, recurrent effusions, and, in rare instances, malignant transformation into synovial chondrosarcoma. Recurrence after surgery is also possible, particularly if diseased synovium is incompletely excised [4]. Diagnosis is based on clinical suspicion, imaging findings, and histopathological confirmation. Radiographs may reveal multiple calcified loose bodies in the late stage, but can appear normal in early disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is the most sensitive modality, capable of detecting both calcified and non-calcified nodules, delineating the extent of synovial proliferation, and identifying involvement of specific compartments. MRI plays a critical role in posterior compartment disease, where standard radiographs often underestimate lesion size and extension, especially in the setting of a massive synovial mass occupying the popliteal fossa [5]. The mainstay of treatment is surgical, with the goals of removing all loose bodies and excising affected synovium to minimize recurrence. Two principal approaches are used: arthroscopic synovectomy and open synovectomy. Arthroscopy offers the advantages of minimal invasiveness, faster rehabilitation, and reduced morbidity and is effective for lesions confined to accessible compartments. However, its utility is limited in cases of extensive posterior compartment involvement or when dealing with a massive synovial mass. In such scenarios, arthroscopic visualization and instrumentation may not permit complete clearance, increasing the risk of residual disease and recurrence [6]. The posterior open approach to the knee, though technically more demanding, offers distinct advantages in these complex cases. It allows direct access to the posterior capsule and surrounding structures, facilitating en bloc removal of large masses and thorough synovectomy while enabling careful protection of critical neurovascular elements, such as the popliteal artery, vein, and tibial nerve. This approach is particularly valuable when the mass is extensive, heavily calcified, or closely associated with the neurovascular bundle. The exposure it provides ensures complete clearance, which is vital in preventing recurrence and mitigating the risk of malignant transformation in long-standing disease [7]. The present case is notable for its rarity and surgical complexity. The patient had a massive synovial chondromatosis confined predominantly to the posterior compartment of the knee – an anatomical location where lesions of this size are seldom reported. The decision to perform a posterior open synovectomy was made to achieve complete excision of the proliferative synovium and removal of all loose bodies, as arthroscopic methods would have been inadequate for the size and location of the lesion. The case highlights that, despite the general preference for minimally invasive techniques, the posterior open approach remains indispensable in select scenarios, particularly when dealing with a large disease burden in anatomically challenging locations [8].

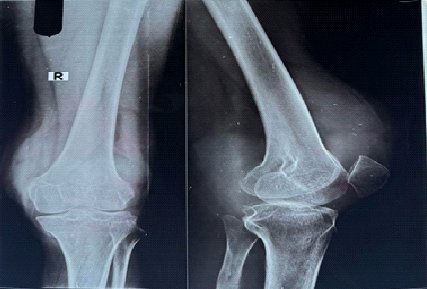

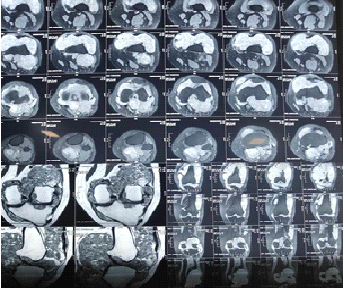

A 42-year-old male, employed as a bank clerk, presented to our orthopedic outpatient department with a chief complaint of gradually progressive pain and swelling in the posterior aspect of his left knee for the past 18 months. The pain was insidious in onset, initially mild and intermittent, but had progressively worsened in intensity over the past 6 months, becoming persistent and affecting daily activities. The patient reported that the pain increased during prolonged standing, walking, or ascending stairs, and was partially relieved by rest and over-the-counter nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs). He also noted a feeling of fullness and a palpable lump in the back of his knee for the past 4 months, which he described as firm and slowly enlarging. There was no history of trauma, recent infection, or previous knee surgery. His medical history was unremarkable, with no known metabolic, rheumatologic, or malignant conditions. He denied any constitutional symptoms such as fever, weight loss, or night sweats. On clinical examination, the patient was of average build and appeared in no acute distress. Inspection of the left knee revealed no gross deformity but a subtle fullness in the popliteal fossa, more prominent when the knee was extended. On palpation, a firm, well-defined, non-tender mass approximately 5 cm × 3 cm was felt in the posterior-medial aspect of the knee, deep to the soft tissues. No warmth or erythema was overlying the swelling. The range of motion of the knee was from 0° extension to 95° flexion, with terminal flexion eliciting pain and a sense of tightness in the posterior aspect. Ligamentous stability tests (anterior drawer, posterior drawer, varus-valgus stress) were normal. Patellar tracking was intact, and there was no crepitus on movement. Neurovascular examination showed intact distal pulses (dorsalis pedis and posterior tibial arteries palpable) and normal sensory and motor function in the lower limb, indicating no neurovascular compromise. Initial radiological evaluation with plain anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the left knee (Fig. 1) demonstrated multiple, small, well-defined calcified loose bodies located predominantly in the posterior aspect of the joint, without significant joint space narrowing or evidence of degenerative changes. The bony contours of the femur and tibia appeared normal, and no fractures or osteophytes were noted. These findings raised the suspicion of synovial chondromatosis. Given the location of the lesion and the possibility of extra-articular extension, MRI was performed for better characterization (Fig. 2, 3).

Figure 1: Pre-operative X-ray (anteroposterior and lateral) showing multiple calcified intra-articular loose bodies.

Figure 2: Magnetic resonance imaging images demonstrating multiple T2 hyperintense lobulated nodules in suprapatellar pouch.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging images demonstrating multiple T2 hyperintense lobulated nodules in anterior joint space.

MRI of the left knee revealed a lobulated, well-marginated lesion in the posterior compartment of the joint, adjacent to the posterior capsule and extending into the popliteal fossa. The lesion was hypointense on T1-weighted images and heterogeneously hypointense to hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, with multiple discrete nodules suggestive of cartilaginous loose bodies. Some nodules showed central areas of low signal intensity consistent with calcification. There was associated mild joint effusion, but no significant synovial thickening in the anterior or medial compartments. The posterior cruciate ligament (PCL) was intact, and the surrounding neurovascular structures — including the popliteal artery and vein — appeared uninvolved, though in proximity to the lesion. These imaging findings were strongly suggestive of localized synovial chondromatosis confined predominantly to the posterior compartment of the knee.

Routine laboratory investigations, including complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, and C-reactive protein, were within normal limits, reducing the likelihood of infection or inflammatory arthropathy. Serum calcium, phosphate, and alkaline phosphatase levels were also normal. Based on the clinical and imaging findings, the differential diagnoses considered included synovial chondromatosis, pigmented villonodular synovitis, lipoma arborescens, and intra-articular osteochondral loose bodies secondary to osteoarthritis. However, the absence of hemosiderin-related blooming on MRI, lack of fatty signal intensity, and the characteristic multiple cartilaginous nodules with calcifications favored the diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis. Given the localized posterior compartment involvement and the firm, calcified nature of the loose bodies, arthroscopic removal was deemed technically challenging and potentially incomplete. Therefore, a decision was made to proceed with posterior open synovectomy to ensure complete excision and minimize recurrence risk. Pre-operative planning included reviewing detailed MRI images to map the extent of the lesion, identifying the safest surgical corridor to avoid neurovascular injury, and planning the patient’s post-operative rehabilitation. The patient was counseled regarding the nature of the condition, surgical approach, possible risks, and the need for histopathological confirmation. Under spinal anesthesia, with the patient in the prone position, the left knee was prepared and draped. A posterior longitudinal incision was made along the medial border of the popliteal fossa. Careful dissection was performed through the subcutaneous tissue, identifying and protecting the small saphenous vein and the sural nerve. The interval between the semimembranosus and medial head of the gastrocnemius was developed, providing access to the posterior capsule. The popliteal artery, vein, and tibial nerve were visualized and safeguarded throughout the procedure. The posterior capsule was incised longitudinally, revealing multiple pearly-white, cartilaginous loose bodies ranging from 5 mm to 15 mm in diameter. These were embedded within hypertrophic synovium, which was excised en bloc. All visible loose bodies were meticulously removed, and the synovial lining was thoroughly debrided. The joint was irrigated with normal saline to remove any microscopic debris. Hemostasis was achieved, and the capsule was closed with absorbable sutures. Layered closure of the skin was performed, and a sterile compression dressing was applied. Intraoperative findings confirmed localized synovial chondromatosis confined to the posterior compartment, without anterior extension. Approximately more than 30 loose bodies (Fig. 4) were retrieved, along with hypertrophic synovium, all of which were sent for histopathological examination.

Postoperatively, the patient was kept in a compression bandage and monitored for neurovascular status, which remained intact. Early gentle range-of-motion exercises were initiated on the second post-operative day to prevent stiffness. Weight-bearing was allowed as tolerated with crutches from the 3rd day, progressing to full weight-bearing by the end of the first post-operative week. Pain was managed with NSAIDs and cryotherapy. Histopathology revealed nodules of hyaline cartilage with clusters of benign chondrocytes, surrounded by synovial connective tissue, confirming the diagnosis of synovial chondromatosis. There was no evidence of atypia or malignancy (Fig. 5, 6, 7). At the 3-week follow-up, the patient demonstrated significant improvement in pain and function, with a painless range of motion from 0° to 120°. Swelling had resolved, and the surgical scar had healed well (Fig. 8). By the 3-month follow-up, the patient had returned to his pre-symptom activity level and resumed his occupational duties without limitations. MRI performed at 6 months showed no evidence of recurrence, with a clear posterior compartment and no new loose bodies. At the 1-year follow-up, the patient remained symptom-free, with a maintained full range of motion and no clinical or radiological signs of recurrence.

Synovial chondromatosis of the knee is a rare, benign, proliferative disorder of the synovium characterized by cartilaginous metaplasia and formation of multiple nodules within the joint, bursa, or tendon sheath. Although the knee is the most commonly affected joint, involvement is usually intra-articular and located in the anterior or general compartments. Isolated or predominant posterior compartment disease, especially with a massive synovial mass, is extremely uncommon and presents unique diagnostic and surgical challenges (Vasudevan et al. [1]). The posterior compartment of the knee is a complex anatomical region containing critical neurovascular structures, including the popliteal artery and vein, tibial nerve, and common peroneal nerve, as well as the PCL and posterior joint capsule. Pathology in this area, particularly a large mass of synovial chondromatosis, can be difficult to access without risking injury to these structures (Singh et al.)[3]. For this reason, surgical approach selection is critical. Arthroscopic techniques, while minimally invasive, often have limited visualization and instrumentation angles in the posterior compartment, particularly when the lesion is extensive, calcified, or located deep within the popliteal fossa. In such cases, an open posterior approach allows for direct visualization, safe dissection, and thorough removal of diseased synovium and loose bodies (Zeleke et al. [8]). In the present case, MRI revealed a well-defined, lobulated, multi-nodular lesion in the posterior compartment of the knee, closely related to the popliteal neurovascular bundle. The sheer size and posterior localization of the mass made posterior open synovectomy the preferred option. The posterior approach, typically through a longitudinal or curvilinear incision along the popliteal fossa, provides direct access to the posterior capsule after careful identification and protection of the small saphenous vein, sural nerve, and popliteal vessels (Evenski et al. [9]). The approach can be modified medially or laterally depending on the lesion’s location. In our patient, the posteromedial approach between the semimembranosus tendon and the medial head of the gastrocnemius offered adequate exposure while minimizing neurovascular risk. Several studies have highlighted the technical advantages of the posterior approach in similar settings. Primaputra et al. [10] reported that in cases where posterior compartment disease is extensive, open posterior exposure is superior to arthroscopic posterior portals in terms of complete removal and recurrence prevention. Similarly, Rai et al. [11] described cases of posterior knee synovial chondromatosis where arthroscopy was incomplete due to the bulk of the mass and restricted access, necessitating conversion to open surgery. These reports align with our intraoperative experience, where direct visualization allowed for meticulous synovectomy, retrieval of all loose bodies, and preservation of vital structures. Massive synovial chondromatosis, as encountered in our case, further complicates surgical management. Large lesions may cause pressure effects on adjacent neurovascular structures, increase the risk of stiffness, and accelerate degenerative joint changes if untreated. The removal of such a large mass through arthroscopic portals can be technically challenging, as fragmentation of nodules may occur, increasing the risk of retained loose bodies and recurrence. Open posterior synovectomy enables en bloc removal of large nodules, which may reduce operative time and improve completeness of excision. A case by Prabowo et al. [12] described the removal of over 100 loose bodies from the posterior compartment of a knee via open surgery, emphasizing that massive disease burdens are best handled with open access. Our patient’s post-operative course was uneventful, with early initiation of rehabilitation to prevent stiffness and restore function. Recurrence is a well-recognized complication of synovial chondromatosis, with reported rates ranging from 3% to 23% depending on surgical completeness Gangwar et al. [13] and Afzal et al. [14]. It is generally accepted that complete synovectomy, rather than loose body removal alone, is essential to minimize recurrence (Moorthy et al. [15]). In posterior compartment disease, open access facilitates more thorough synovectomy, potentially lowering recurrence rates compared to arthroscopic partial removal. In reviewing the literature, multiple cases have been documented where the posterior approach was chosen for similar reasons. Park et al. [16] reported a case of giant posterior knee synovial chondromatosis where arthroscopy was deemed inadequate, and an open posterior approach achieved complete removal and a recurrence-free outcome at 2 years. In another study by Efrima et al. [17], a patient with PCL-associated synovial chondromatosis underwent open posterior synovectomy with good functional recovery. These parallels reinforce that lesion size, location, and relation to neurovascular structures should dictate surgical approach rather than adherence to a single favored technique. While the posterior approach offers clear advantages in massive posterior lesions, it is not without limitations. It is technically demanding, requires familiarity with posterior knee anatomy, and carries risks of neurovascular injury if dissection is not meticulous. In addition, post-operative wound complications and stiffness can occur, though these risks are mitigated by careful technique and early mobilization (Terra et al. [18]).

Histopathological analysis in our case confirmed benign synovial chondromatosis, without evidence of malignancy. While rare, malignant transformation to synovial chondrosarcoma has been documented, particularly in long-standing or recurrent disease Duif et al. [19] and Babu et al.(2020) [20]. Complete removal of all abnormal synovium is therefore also important for mitigating long-term oncologic risk. Comparatively, arthroscopy remains the gold standard for most anterior and general compartment synovial chondromatosis due to its minimally invasive nature and favorable recovery profile Hellwinkel et al. [21] and Cardoso et al. [22]. However, as demonstrated by our case and others in the literature, the posterior open approach remains indispensable for massive or isolated posterior lesions where arthroscopy cannot provide complete access or clearance. In select patients, a combined approach-arthroscopy for anterior lesions and open posterior synovectomy for posterior lesions-may be appropriate, as described by Poyser et al. [23] and Odluyurt et al. [24].

Synovial chondromatosis localized to the posterior compartment of the knee, particularly when presenting as a massive synovial mass, remains a rare and surgically demanding condition due to the complex anatomy of the popliteal fossa. The dense neurovascular structures and deep posterior capsule pose significant challenges for complete excision. In such cases, the posterior open approach offers superior visualization and access compared to arthroscopy, enabling en bloc removal of large nodules and meticulous synovectomy while minimizing neurovascular injury. Complete removal is critical to prevent recurrence, as residual diseased synovium or loose bodies serve as a nidus for disease persistence. Pre-operative MRI is essential for accurate assessment of lesion size, extent, and relation to adjacent neurovascular structures, informing surgical planning and approach. Timely, thorough excision through the posterior open route alleviates symptoms, preserves joint function, delays degenerative changes, and reduces the risk of malignant transformation. With careful technique and neurovascular preservation, this approach yields favorable functional outcomes and should be considered the surgical strategy of choice for massive posterior synovial chondromatosis.

For massive synovial chondromatosis in the posterior knee, the posterior open approach offers superior access and neurovascular protection, minimizing recurrence risk.

References

- 1. Vasudevan R, Jayakaran H, Ashraf M, Balasubramanian N. Synovial chondromatosis of the knee joint: Management with arthroscopy-assisted “sac of pebbles” extraction and synovectomy. Cureus 2024;16:e69378. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Rai AK, Bansal D, Bandebuche AR, Rahman SH, Prabhu RM, Hadole BS. Extensive synovial chondromatosis of the knee managed by open radical synovectomy: A case report with review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2022;12:19-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Singh S, Neelakandan K, Sood C, Krishnan J. Disseminated synovial chondromatosis of the knee treated by open radical synovectomy using combined anterior and posterior approaches. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2014;5:157-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Wahab H, Hasan O, Habib A, Baloch N. Arthroscopic removal of loose bodies in synovial chondromatosis of shoulder joint, unusual location of rare disease: A case report and literature review. Ann Med Surg (Lond) 2019;37:25-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Chraibi O, Rajaallah A, Lamris MA, El Kassimi CE, Rafaoui A, Rafai M. Concurrent arboreal lipoma and synovial chondromatosis in an osteoarthritic knee: Insights from a rare case study-a surgical case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2024;119:109786. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Zanna L, Secci G, Innocenti M, Giabbani N, Civinini R, Matassi F. The use of posteromedial portal for arthroscopic treatment of synovial chondromatosis of the knee: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2022;16:457. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Braun S, Flevas DA, Sokrab R, Ricotti RG, Rojas Marcos C, Pearle AD, et al. De novo synovial chondromatosis following primary total knee arthroplasty: A case report. Life (Basel) 2023;13:1366. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Zeleke SS, Nigussie KA, Mesfin YM, Fentie WM, Stein M, Molla DK. Disseminated synovial chondromatosis of the knee treated by open radical synovectomy using staged combined anterior and posterior approaches: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2025;19:152. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Evenski AJ, Stensby JD, Rosas S, Emory CL. Diagnostic imaging and management of common intra-articular and peri-articular soft tissue tumors and tumorlike conditions of the knee. J Knee Surg 2019;32:322-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Primaputra MR, Malau VD, Budhy F, Yudhistira P. Comparative analysis of synovectomy and total knee replacement in knee joint synovial chondromatosis: A case series. Narra J 2024;4:e1115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Rai AK, Bansal D, Bandebuche AR. Disseminated synovial chondromatosis of the knee managed by combined anterior and posterior approaches: A rare case report. J Orthop Rep 2022;1:100082. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Prabowo Y, Saleh I, Pitarini A, Junaidi MA. Management of synovial chondromatosis of the hip by open arthrotomy debridement only VS total hip replacement: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2020;74:289-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Gangwar S, Singh A, Bhasin VB. Arthroscopic management of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder: A case report. J Arthrosc Surg Sports Med 2021;3:53-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Afzal S, Kazemian G, Baroutkoub M, Omrani FA, Ahmadi A, Darestani RT. Arthroscopic management of ankle primary synovial chondromatosis (Reichel’s syndrome): A case report with literature review. Int J Surg Case Rep 2023;111:108832. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Moorthy V, Tay KS, Koo K. Arthroscopic treatment of primary synovial chondromatosis of the ankle: A case report and review of literature. J Orthop Case Rep 2020;10:54-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Park JP, Marwan Y, Alfayez SM, Burman ML, Martineau PA. Arthroscopic management of synovial chondromatosis of the shoulder: A systematic review of literature. Shoulder Elbow 2022;14 Suppl 1:5-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Efrima B, Safran N, Amar E, Bachar Avnieli I, Kollander Y, Rath E. Simultaneous pigmented villonodular synovitis and synovial chondromatosis of the hip: Case report. J Hip Preserv Surg 2018;5:443-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Terra BB, Moraes EW, Souza AC, Cavatte JM, Teixeira JC, Nadai AD. Arthroscopic treatment of synovial osteochondromatosis of the elbow. Case report and literature review. Rev Bras Ortop 2015;50:607-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Duif C, Von Schulze Pellengahr C, Ali A, Hagen M, Ficklscherer A, Stricker I, et al. Primary synovial chondromatosis of the hip – is arthroscopy sufficient? A review of the literature and a case report. Technol Health Care 2014;22:667-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Babu S, Vaish A, Vaishya R. Outcomes of total knee arthroplasty in synovial osteochondromatosis: A comprehensive review. J Arthrosc Joint Surg 2020;7:111-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Hellwinkel JE, Farmer RP, Heare A, Smith J, Donaldson N, Fadell M, et al. Primary intra-articular synovial sarcoma of the knee: A report of two cases and review of the literature. Int J Radiol Imaging Technol 2018;4:1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Cardoso RC, Malheiro F, Pereira B. Management of primary synovial osteochondromatosis in the ankle joint with a combined posterior-anterior arthroscopic procedure: A case report. Cureus 2024;16:e60843. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Poyser E, Morris R, Mehta H. Primary synovial osteochondromatosis of the shoulder: A rare cause of shoulder pain. BMJ Case Rep 2018;11:e227281. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Odluyurt M, Orhan Ö, Sezgin EA, Kanatlı U. Synovial chondromatosis in unusual locations treated with arthroscopy: A report of three cases. Joint Dis Relat Surg Case Rep 2022;1:63-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]