This article highlights the importance of recognizing and appropriately managing anomalous anterolateral meniscofemoral ligaments (ALMFL), advocating for resection to preserve natural knee mechanics and improve patient outcomes.

Mr. Theodore Joaquin, Georgetown University School of Medicine, Washington, DC, United States. E-mail: taj49@georgetown.edu

Introduction: Anomalous anterolateral meniscofemoral ligaments (ALMFLs) are rare and underreported anatomical variations that are crucial for knee stability and joint biomechanics. This case report presents two instances of ALMFL, one associated with an anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) tear and the other with congenital ACL absence. These cases are significant as they contribute to the limited body of literature on ALMFL and its management, highlighting the importance of recognizing this anomaly during knee surgeries.

Case Report: The first case involves a 28-year-old female with a torn ACL following a skiing injury. During ACL reconstruction, an ALMFL was discovered, attached to the lateral meniscus but not affecting its function. The second case is a 35-year-old female with a history of a meniscal tear, presenting with knee instability and pain. An ALMFL was identified during surgery, alongside a discoid meniscus and complex meniscal tear. Both patients underwent debridement of the ALMFL, with favorable recovery outcomes.

Conclusion: This case report underscores the importance of recognizing ALMFL as a potential anatomical variation during knee surgery. Surgeons should be aware of this structure’s presence to avoid misdiagnosis or unnecessary interventions. The management approach of debriding the ALMFL to restore natural knee biomechanics has shown positive results, suggesting a viable strategy for future cases. This report advances our understanding of knee anomalies, specifically in patients with ACL injuries or congenital absence, and highlights the need for personalized surgical approaches in these scenarios.

Keywords: Anterolateral meniscofemoral ligament, knee surgery, anterior cruciate ligament tear, meniscal injury, anatomical variants.

Anomalous insertions of the meniscus into the femur are not a new subject of study. However, the majority of the cases documented in the literature primarily focus on the anteromedial meniscofemoral ligaments (AMMFL) [1-8]. In contrast, investigations into the topic of meniscus-to-femur insertions tend to highlight the ligaments of Humphreys and Wrisberg [9-11]. While these structures are important, they are not considered anomalous. In this case report, we describe two rare cases of anterolateral meniscofemoral ligaments (ALMFLs). While there are a few reports of these ligaments, they often are accompanied by a congenital absence of the anterior cruciate ligament (ACL) or hypoplastic ACL [12,13]. We believe the second patient we present to be the third reported case of this rare phenomenon. Kim et al., first described an ALMFL without a congenital ACL anomaly, though their case involved an ALMFL coexisting with an AMMFL [14]. This is the closest report to our first patient’s anomalous ALMFL, which we believe to be the only instance where the ALMFL is present without any associated ACL malformation or redundant tissue. We discuss here the cases of patients who presented to the same physician for knee pain following trauma. Arthroscopic photographs and operative notes are included to best depict the anatomical variants.

Case 1

A 28-year-old female presented to our institution with left knee pain and instability for 6 weeks. Before pain onset, the patient sustained a fall while skiing. She reported feeling two pops in her knee upon falling. Her pain was associated with weakness and persisted at rest. Physical examination of the left knee revealed mild effusion with tenderness at the anterior knee joint. The Lachman test was positive with a grade 2 score. She was stable to varus and valgus stress tests. Dial test was negative. She had full range of motion with a mild antalgic gait. Perioperative magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) demonstrated a full-thickness ACL tear with a typical bone bruise pattern (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: (a) Sagittal magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) showing Patient 1’s anterior cruciate ligament tear. (b) Sagittal MRI showing Patient 1’s resultant bone bruise.

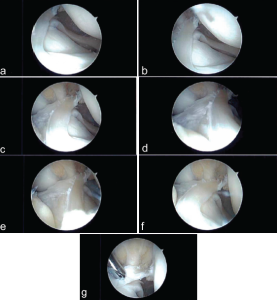

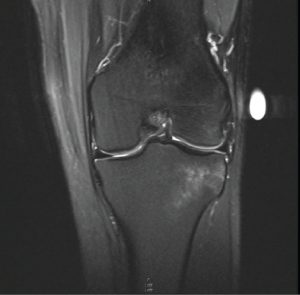

Arthroscopy was done to reconstruct the ACL with quadriceps autograft. The midsubstance ACL tear was apparent. There were no abnormalities appreciated on the cartilaginous surfaces throughout, and there were no disruptions to the body of the plateau. Both the medial and lateral menisci were intact. However, an anatomic variant was discovered at the lateral meniscus. The anterior horn continued superiorly and attached to the torn ACL, which was better appreciated on the MRI during re-review postoperatively (Fig. 2 and 3). Due to the superfluous nature of the variant, the tear did not impact the body of the meniscus in any way. The root of the lateral meniscus remained intact. The redundant tissue was gently debrided away without compromising the root.

Figure 2: (a-g) Patient 1’s anterolateral meniscofemoral ligament viewed through an anteromedial arthroscopic porthole.

Figure 3: Coronal magnetic resonance imaging showing Patient 1’s anterior horn of the lateral meniscus extending into the anterior cruciate ligament footprint.

This patient’s post-operative course was uncomplicated. She was able to initiate a running progression program 3 months after her surgery and focused heavily on strengthening exercises with her physical therapist. No formal outcome scoring was assessed. One year after her surgery, she reported excellent overall recovery, with running and activity resumption to pre-injury levels. She noted that, while her repaired knee felt just as stable as her non-operative knee, the muscles in her non-operative leg remained tighter and stronger compared to the operative leg. Despite this, she has returned to full participation in her active lifestyle without restriction. She continues to work on her physical therapy exercises to equalize the strength in her legs.

Case 2

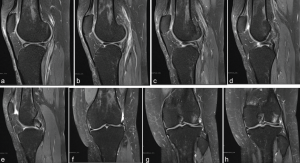

A 35-year-old female presented to our institution with left knee pain. She has a history of a meniscus tear from 16 years ago, which was managed nonoperatively at the time due to minimal symptoms. Over the past month, her pain has become significant. There has been no new injury. She reported pain on both the medial and lateral aspects of her left knee, accompanied by swelling. The pain worsened with squatting and had been experiencing instability and intermittent locking in the knee. In addition, she felt instability in her knee for about a year and a half, which has prevented her from exercising. On examination, the patient exhibited a normal gait and a full range of motion. On the left knee, there was mild tenderness and mild effusion along the lateral joint line and slight pain with flexion during the McMurray test. Perioperative MRI demonstrated a complex bucket-handle tear through the anterior horn into the body of the lateral meniscus with flipped torn meniscal fragments medially into the tibiofemoral joint space (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: (a-e) Series of sagittal magnetic resonance imagings (MRIs) of Patient 2 displaying a sequence from lateral to medial. The anterolateral meniscofemoral ligaments can be seen continuing from the anterior horn on the lateral meniscus and inserting into the anterior cruciate ligament footprint. This was interpreted as a flipped bucket handle tear prior to surgery. (f-h) Series of coronal MRIs of Patient 2 displaying meniscal tissue within the intercondylar notch. On re-review, the anterolateral meniscofemoral ligament can be seen inserting into the lateral aspect of the intercondylar notch.

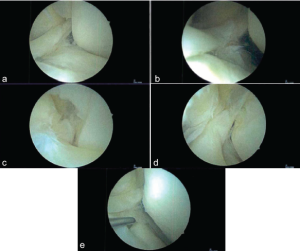

During arthroscopy, there were grade 1–2 changes in the patellofemoral compartment and grade 2 changes in the medial compartment. A radial tear noted in the midsubstance of the medial meniscus was debrided to stable edges. There were grade 2 and minor grade 3 changes in the lateral compartment. The lateral compartment showed abnormal meniscal anatomy evidenced by a partial discoid meniscus with a large intra-meniscal attachment connecting the anterior and posterior horns through the notch. This portion was unstable and mobile, while the midportion of the meniscus in its normal location had complex tearing. The midsubstance of the meniscus was debrided to stable edges, performing a partial meniscectomy. The unstable intra-meniscal attachment connecting the anterior and posterior horns was also debrided. In addition, a separate attachment from the anterior horn of the lateral meniscus to the native ACL origin on the medial aspect of the lateral femoral condyle was found (Fig. 5). This anomalous tissue was debrided. The anterior horn was attached to the root and was stable, and the posterior horn had a partial root attachment and a large meniscofemoral ligament attachment, making it stable. There was no evidence of ACL present in the notch, but the bony anatomy of the notch was normal. Therefore, the decision was made to debride the redundant tissue, restoring normal meniscal shape. On post-operative review of the patient’s MRI, the ALMFL could be appreciated on both the coronal and sagittal images inserting into the native ACL footprint (Fig. 4).

Figure 5: (a-e) Patient 2’s anterolateral meniscofemoral ligament viewed through an anteromedial arthroscopic porthole.

Similar to Patient 1, this patient’s post-operative course was uneventful. At her initial visit 1 week following surgery, she reported no pain and was not taking any medication. One month following surgery, there was some concern that an ACL reconstruction may be needed after a grade 1 Lachman test and a slight locking feeling in the knee, despite no reported instability. However, a month later, these symptoms completely resolved. With no pain and complete satisfaction with her recovery, she began to resume normal activities. We agreed to continue monitoring her progress and reconvene as needed. Ten months following surgery, she reported an active lifestyle consisting of gym and walking routines. Although no formal outcome scores were collected, the patient did not report any ongoing limitations or restrictions experienced due to her injury or subsequent repair.

This report describes two cases of aberrant anatomic structures in the knees of otherwise healthy middle-aged female patients. The first case is a 28-year-old female found to have a full-thickness tear of her ACL after a skiing injury and the second is a 35-year-old female with a flare of her chronic meniscal tear and general knee instability. Both patients were incidentally found to have ALMFL. To the authors’ knowledge, these are only the 4th and 5th cases of an ALMFL reported [12-14].

Two of the prior reported cases of ALMF also involved congenital absence of the ACL with the aberrant ligament following the path of the native ACL [12,13]. Razi et al., chose to leave the anomalous ligament intact to act as a secondary stabilizer after ACL reconstruction [12]. The patient in that case report had an overall good outcome though did not regain full range of motion until 14 months postoperatively. Kim et al., reported a case of both an ALMFL and an AMMFL in a patient with a radial tear of the lateral meniscus [14]. They also left the ligaments intact and performed an arthroscopic partial meniscectomy of the radial tear. The patient was noted to have hypermobility of the anterior horn, which was treated with strengthening exercises and activity modification with positive outcomes.

In both presented cases, the anomalous ALMFL was debrided down to the natural anterior horn of the lateral meniscus to best restore natural joint mechanics. The first patient did not have a history of ACL agenesis, so it was felt that maintaining the ALMFL could lead to stiffness in the setting of ACL reconstruction and was thus resected. In the second case, no ACL was observed intraoperatively. The bony anatomy of the intercondylar notch was normal, so the redundant tissue was debrided in an effort to restore normal meniscal shape. Staged ACL reconstruction was discussed with the patient postoperatively. At 3 months following surgery for the first patient and 2 months for the second, both patients were progressing without issue with physical therapy and were beginning running progression programs.

The present case report is significant as it offers an alternative treatment for patients with an anomalous ALMFL, resecting the ligament to preserve the anterior horn and restoring natural knee biomechanics. Orthopedic surgeons should be aware of this anatomic anomaly with an appropriate treatment plan on a case-by-case basis, and multiple treatment strategies have been proposed. Future case reports and outcomes will help us determine the optimal treatment for these patients.

This article highlights the importance of recognizing anomalous anterolateral meniscofemoral ligaments (ALMFL) during knee surgery, emphasizing that these variations should be considered during the diagnosis and treatment of knee injuries. The report advocates for the resection of the ALMFL to restore natural knee biomechanics, which has shown positive outcomes in the presented cases, and it calls for greater awareness and tailored treatment strategies in managing patients with such anatomical anomalies.

References

- 1. Alves TA, Braun MA, Duarte ML, Santosc LR. Anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament-A rare finding. Morphologie 2022;106:124-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Coulier B, Himmer O. Anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament of the knee: CT and MR features in 3 cases. JBR-BTR 2008;91:240-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Hamada M, Miyama T, Nagayama Y, Shino K. Repair of a torn medial meniscus with an anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament in an anterior cruciate ligament-injured knee. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:826-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kim YM, Joo YB. Anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament of the anterior horn of the medial meniscus: Clinical, magnetic resonance imaging, and arthroscopic features. Arthroscopy 2018;34:1590-600. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Luco JB, Di Memmo D, Gomez Sicre V, Nicolino TI, Costa-Paz M, Astoul J, et al. Clinical, imaging, arthroscopic, and histologic features of bilateral anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament: A case report. World J Methodol 2023;13:359-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Mariani PP, Battaglia MJ, Torre G. Anomalous insertion of anterior and posterior horns of medial meniscus. Case report. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:823. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Soejima T, Murakami H, Tanaka N, Nagata K. Anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament. Arthroscopy 2003;19:90-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Trinh JM, De Verbizier J, Lecocq Texeira S, Gillet R, Arab Abou W, Blum A, et al. Imaging appearance and prevalence of the anteromedial meniscofemoral ligament: A potential pitfall to anterior cruciate ligament analysis on MRI. Eur J Radiol 2019;119:108645. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Alatakis S, Naidoo P. MR imaging of meniscal and cartilage injuries of the knee. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2009;17:741-56, vii. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bintoudi A, Natsis K, Tsitouridis I. Anterior and posterior meniscofemoral ligaments: MRI evaluation. Anat Res Int 2012;2012:839724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Pekala PA, Rosa MA, Lazarz DP, Pekala JR, Baginski A, Gobbi A, et al. Clinical anatomy of the anterior meniscofemoral ligament of humphrey: An original MRI study, meta-analysis, and systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med 2021;9:2325967120973192. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Razi M, Mazoochy H, Ziaei Ziabari E, Dadgostar H, Askari A, Arasteh P. Anterolateral meniscofemoral ligament associated with ring-shaped lateral meniscus and congenital absence of anterior cruciate ligament, managed with ligament reconstruction. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2020;8:112-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Silva A, Sampaio R. Anterior lateral meniscofemoral ligament with congenital absence of the ACL. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2011;19:192-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Kim YM, Joo YB, Yeon KW, Lee KY. Anterolateral meniscofemoral ligament of the lateral meniscus. Knee Surg Relat Res 2016;28:245-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]