Ganglioglioma is a diagnostic challenge to spine surgeons and the current treatment of choice is complete surgical excision while preserving normal spinal cord function.

Dr. Amaresh Cadapa Prahallad, Department of Spine Surgery, Sanjay Gandhi Institute of Trauma and Orthopaedics, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: amareshprahallad@gmail.com

Introduction: Ganglioglioma is a slow growing benign intradural intramedullary neuroepithelial tumor. Around 1–2% of all spinal tumors are gangliogliomas. Concurrent scoliosis with ganglioglioma is a rare entity with a few cases reported in literature.

Case Report: Here, we present a case report of a 17-year-old boy with thoracic intramedullary ganglioglioma with scoliosis and no neurological deficits. The surgical management comprised D5 – D10 laminectomy, posterior midline myelotomy, and near total tumor resection along with instrumentation from D4 to L1 for deformity correction. Patient recovered well with no post-operative neurodeficits. Follow-up at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years was suggestive of improved patient comfort, reduced pain, improved posture, and no new-onset neurological deficits.

Conclusion: Ganglioglioma is a rare intramedullary tumor of spinal cord typically affecting pediatric age group which can be associated with spine deformity. The treatment of choice for Intraspinal gangliogliomas is complete surgical resection. The aim of surgery is to strike a balance between the extent of tumor resection and preserving the normal spinal cord function without causing iatrogenic neurological deficits.

Keywords: Ganglioglioma, intramedullary tumor, spinal cord tumor.

Ganglioglioma is a benign neuroepithelial tumor that grows slowly; it makes up 0.4–6.25% of all primary tumors of the central nervous system (CNS) [1]. Although Loretz was the first to describe them in 1870, Perkins was the first to propose the term “ganglioglioma” [2]. Majority of gangliogliomas are benign and mostly affect the temporal lobes arising in the supratentorial compartment [3]. Around 1–2% of all spinal tumors are intramedullary spinal gangliogliomas, which make up 35–40% of pediatric intramedullary spinal tumors. Here, we present a rare case report of intramedullary spinal cord ganglioglioma with scoliotic deformity.

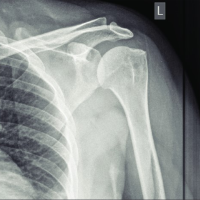

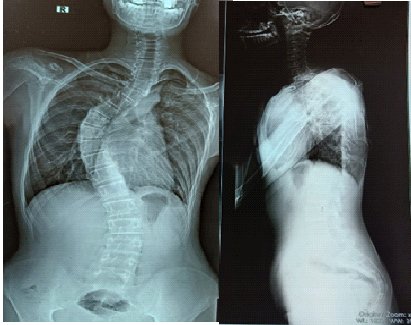

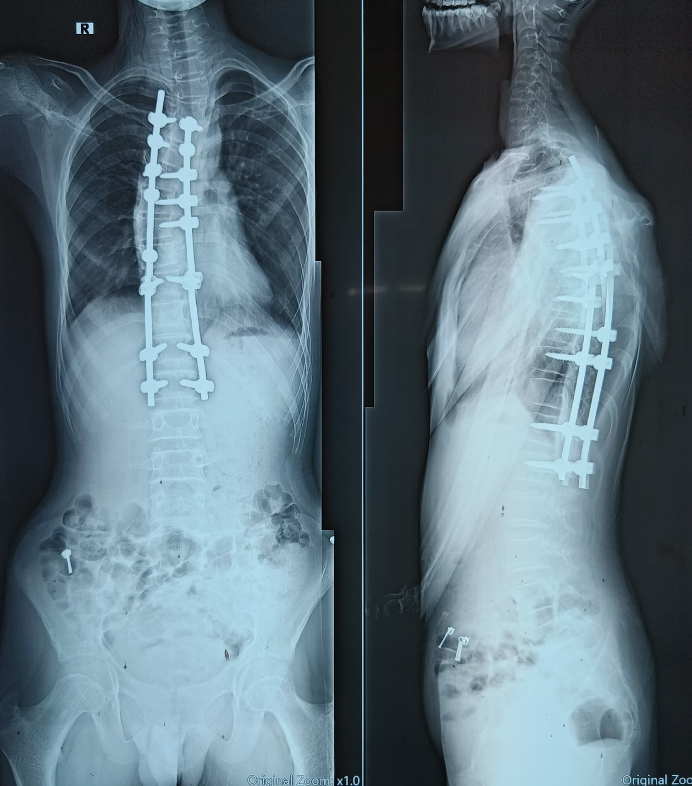

A 17-year-old boy visited the Spine OPD at Sanjay Gandhi Institute of Trauma and Orthopedics, Bangalore, with the complaints of back pain and progressive deformity for 4 years (Fig. 1). On clinical examination and X-rays, the patient had right sided thoracic scoliosis with no neurological deficits (Fig. 2).

Figure 1: Clinical image of scoliotic deformity.

Figure 2: X-ray showing scoliosis with the right main thoracic curve.

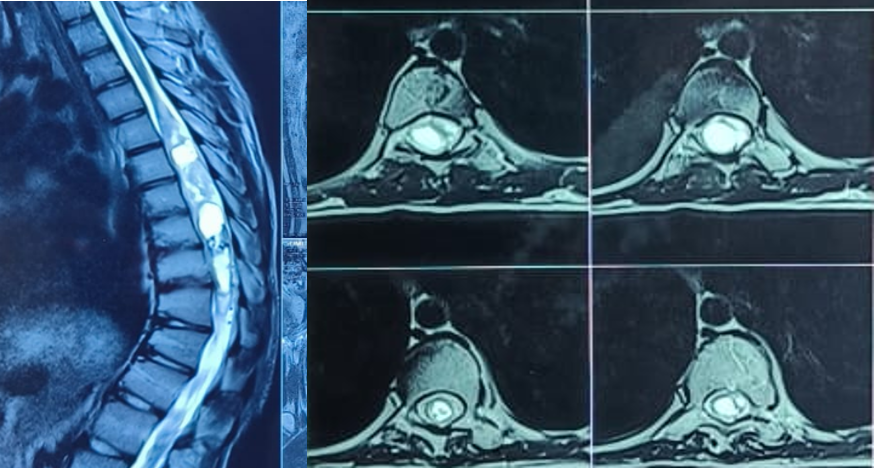

However, his lower limb deep tendon reflexes were exaggerated with grade 3+. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed well defined expansile, intramedullary predominantly cystic lesion extending from D5 to D10 spinal cord levels with moderately enhancing solid component, along with structural abnormalities (Fig. 3). These features were suggestive of an intramedullary neoplastic lesion likely to be astrocytoma. Surgical plan was as follows; tumor resection with deformity correction and further management based on the biopsy report.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrating well-defined, mildly expansile, intramedullary cystic lesion extending from D5 to D10 levels with moderately enhancing solid components.

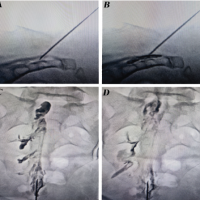

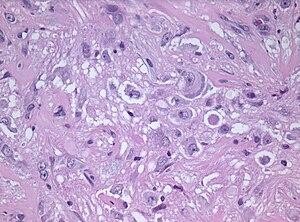

Patient underwent D5 – D10 laminectomy, posterior midline myelotomy and near total tumor resection along with instrumentation from D4 to L1 was done for deformity correction under neuromonitoring (Fig. 4 and 5). Intraoperatively, greyish yellow, non-friable, firm, and poorly differentiated tumor tissue was noted. In view of possible iatrogenic neurological deficits and poorly differentiated tumor, complete resection could not be achieved. Histopathological reports were suggestive of low-grade glioneuronal tumor compatible with ganglioglioma (Fig. 6). As the tumor was of Grade 1 WHO, adjuvant chemotherapy or radiotherapy was not indicated. Post-operative physiotherapy for posture and gait correction was initiated. In due course of follow-up at 6 months, 1 year, and 2 years, patient was comfortable, pain had reduced, his posture had improved, and there were no new-onset neurological deficits.

Figure 4: Intraoperative image of posterior midline myelotomy.

Figure 5: Post-operative X-ray.

Figure 6: Histopathological image showing large neuronal cells and hyperchromatic nuclei (Sourced from Department of Pathology, NIMHANS Bangalore).

Gangliogliomas are tumors of the CNS that are made up of both glial and neuronal components. The glial elements consist of astrocytes with large and relatively mature neoplastic neurons [4]. Atypical features have also been reported to varying degrees in gangliogliomas, including cytologic atypia, necrosis, increased mitotic activity, and increased cellularity [5]. The second most common cause of pediatric spinal tumors is ganglioglioma [1]. BRAF V600E mutation in spinal ganglioglioma has been described in a few series recently [6]. The incidence of spinal cord gangliogliomas is highest in the first three decades of life, but they can occur at any age between 2.5 years and 80 years [3]. Selective predilection for cervical cord followed by thoracic cord is seen, though they have been reported in all regions of the spinal cord [3]. The involvement of conus is the least common site of affection as per reported cases of literatures [7]. In addition, concurrent scoliosis has been recorded in certain ganglioglioma instances. However, the precise relationship between gangliogliomas and neuropathic spinal deformity remains unclear, and the pathogenesis has not been elucidated. [8]. Neurotrophic activity of the spinal nerve may be impacted by ganglioglioma, which could lead to a downstream muscular imbalance and asymmetrical trunk muscle weakening. Clinical presentation with progressive myelopathy and other neurological findings depending on the location of the tumor have been documented. Other studies have reported sphincter dysfunctions, sensory deficiencies, gait abnormalities, motor deficits, and discomfort [3]. With imaging alone, it is almost impossible to distinguish ganglioglioma from other more prevalent intramedullary neoplasms [9]. Common MRI findings include a circumscribed solid or mixed solid and cystic mass spanning a long segment of the cord with hypointense T1 signal and hyperintense T2 signal in the solid component. Highly variable enhancement patterns are seen, ranging from minimal to marked, and may be solid, rim, or nodular. Reactive scoliosis may be accompanied by peritumoral cysts, syringomyelia, and adjacent cord edema [9]. In general, gangliogliomas are benign WHO grade I tumors; however, if there are anaplastic alterations in the glial component, they are regarded as WHO grade III tumors (anaplastic ganglioglioma). There have only been a few reports of spinal ganglioglioma undergoing malignant transformation. Gross total surgical resection is the definitive treatment for ganglioglioma, and a good prognosis is expected when this is achieved. However, complete tumor removal may not be possible due to unclear tumor margins and the goal to maintain normal spinal cord tissue, motor, and sensory function [9]. High morbidity rate is encountered even with microsurgical techniques and the extent of resection decides the outcome though arguable. Surgical outcome parameters include recovery, no change in neurological status, and progression of neurological deficit [10]. Concomitant scoliosis invariably hampers identification of the midline during surgical excision of the tumor [8]. Radiation therapy has no role in the treatment with the exception of the WHO grade III anaplastic ganglioglioma. Adjuvant chemotherapy is reserved for anaplastic ganglioglioma, though used anecdotally in partially resected low-grade spinal cord gangliogliomas [9]. Male sex, malignant histological features, and advanced age at diagnosis are all poor prognosis markers for individuals with gangliogliomas [9]. BRAFV600E-mutated gangliogliomas exhibit worse recurrence-free survival compared to BRAFV600E-negative tumors [5]. Compared to cerebral GGs, intraspinal gangliogliomas have a three-fold increased risk of recurrence, and their 5-year survival rate is 89% [1].

Ganglioglioma is a rare intramedullary tumor of spinal cord typically affecting pediatric age group which can be associated with spine deformity. The radiological diagnosis of intramedullary ganglioglioma is challenging, since it does not exhibit any typical and/or pathognomonic radiological characteristics. The treatment of choice for intraspinal gangliogliomas is complete surgical resection. The aim of surgery is to strike a balance between the extent of tumor resection and preserving the normal spinal cord function without causing iatrogenic neurological deficits. Risk of recurrence is higher in the case of spinal cord ganglioglioma and revision surgery might be considered.

Ganglioglioma with scoliosis is a rare presentation and a diagnostic challenge based on radiological investigations alone as it does not exhibit any pathognomonic features. The current accepted treatment of choice is complete surgical resection while aiming to preserve the normal spinal cord function without causing neurological deficits.

References

- 1. Melián KA, López FJ, Imbroda JM, Betancor DR, Pons DR. Intramedullary spinal cord ganglioglioma: Case report and comparative literature review. Neurocirugía (Engl Ed) 2021;32:124-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Vlachos N, Lampros MG, Zigouris A, Voulgaris S, Alexiou GA. Anaplastic gangliogliomas of the spinal cord: A scoping review of the literature. Neurosurg Rev 2022;45:295-304. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Satyarthee GD, Mehta VS, Vaishya S. Ganglioglioma of the spinal cord: Report of two cases and review of literature. J Clin Neurosci 2004;11:199-203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Jallo GI, Freed D, Epstein FJ. Spinal cord gangliogliomas: A review of 56 patients. J Neurooncol 2004;68:71-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Dahiya S, Haydon DH, Alvarado D, Gurnett CA, Gutmann DH, Leonard JR. BRAF(V600E) mutation is a negative prognosticator in pediatric ganglioglioma. Acta Neuropathol 2013;125:901-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Deora H, Sumitra S, Nandeesh BN, Bhaskara Rao M, Arivazhagan A. Spinal intramedullary ganglioglioma in children: An unusual location of a common pediatric tumor. Pediatr Neurosurg 2019;54:245-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Sandeep B, Roy K, Saha SK, Banga MS. Intramedullary spinal ganglioglioma involving the conus with unusual magnetic resonance imaging features. J Spinal Surg 2016;3:114-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Yang C, Li G, Fang J, Wu L, Yang T, Deng X, et al. Intramedullary gangliogliomas: Clinical features, surgical outcomes, and neuropathic scoliosis. J Neurooncol 2014;116:135-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Oppenheimer DC, Johnson MD, Judkins AR. Ganglioglioma of the spinal cord. J Clin Imaging Sci 2015;5:53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Lotfinia I, Vahedi P. Intramedullary cervical spinal cord ganglioglioma, review of the literature and therapeutic controversies. Spinal Cord 2009;47:87-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]