This case report highlights the successful use of ARIF in treating a unstable osteochondral defect in a young, healthy patient, underscoring the importance of considering this diagnosis even in the absence of trauma.

Dr. José I Acosta Julbe, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, University of Puerto Rico, Medical Sciences Campus, San Juan, Puerto Rico, USA. E-mail: jose.acosta14@upr.edu

Introduction: Osteochondral defects cause significant loss of articular cartilage and subchondral bone, often leading to osteoarthritis if untreated. Early diagnosis and intervention are crucial to prevent degenerative joint disease. This case report documents the first successful use of arthroscopic reduction internal fixation for an atraumatic osteochondral defect in a young, healthy individual, demonstrating the potential of this minimally invasive approach.

Case Report: A 27-year-old Hispanic male with no significant medical history presented with restricted left knee extension and occasional locking after recreational swimming. Physical examination showed tenderness along the knee borders, a positive varus stress test, and limited extension. Imaging studies identified a large, unstable osteochondral lesion in the lateral femoral condyle. Arthroscopy confirmed the defect, measuring approximately 4.5 cm × 1.5 cm, and fixation was performed using three headless compression screws. Post-operative recovery was smooth, with the patient regaining full functionality within 3 months and excellent outcomes at the 2-year follow-up visit.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of considering osteochondral defects in young patients with knee pain, even without trauma. The successful use of ARIF for a large, atraumatic osteochondral defect demonstrates the efficacy of minimally invasive techniques in treating such lesions. We underline the importance of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion for this diagnosis in young patients presenting with knee pain.

Keywords: Osteochondral defect, arthroscopic reduction internal fixation, atraumatic knee injury, osteoarthritis, minimally invasive surgery.

Osteochondral defects (OD) are the articular loss of cartilage and subchondral bone, often arising from acute trauma [1,2,3]. These injuries can occur in up to 36% of the population and are commonly linked to osteochondral fractures and anterior cruciate ligament injuries [4,5]. Untreated cartilage injuries can lead to osteoarthritis (OA), which is the 15th highest cause of years lived with disability worldwide [6,7]. The United States’ direct medical costs of OA are estimated at $72 billion [8]. Early diagnosis and treatment of ODs are crucial to prevent the development of degenerative joint disease and reduce the associated socioeconomic burden [9]. Patients with symptomatic OD typically present with nonspecific knee pain and swelling [10]. Knee ODs can be diagnosed either by magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) or at the time of knee arthroscopy [11]; previous studies have reported a prevalence of articular cartilage pathologies of 66% in arthroscopic knee procedures [12,13,14]. The frequency of diagnosed articular cartilage defects is increasing due to the greater use of MRI and the higher accuracy of newer imaging techniques [15,16]. Numerous surgical procedures are available for treating these injuries, including fragment excision, arthroscopic reduction internal fixation (ARIF), and other cartilage restoration or replacement modalities [17].

Fixing unstable osteochondral fragments involves restoring the native hyaline articular surface and repairing the subchondral bone [5,18]. Despite advancements, effectively managing substantial osteochondral lesions remains complex [19]. Rak Choi et al. found satisfactory clinical and radiological outcomes using internal fixation for ankle ODs, and other studies have noted similar success utilizing ARIF for acute traumatic knee chondral lesions [18,20,21]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there is scarce literature regarding the outcomes of patients undergoing ARIF for atraumatic knee ODs. We report the case of a 27-year-old male successfully managed with ARIF after developing an atraumatic OD in the lateral femoral condyle. We obtained written consent from the patient to use his de-identified medical information.

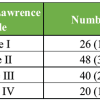

A 27-year-old Hispanic male with no significant medical history visited our orthopedic sports medicine clinic, reporting restricted left knee extension and occasional locking while walking. Despite these issues, he could manage his daily activities with slight difficulty. The symptoms began a month prior during recreational swimming. The patient had limited access to obtaining a medical appointment with the orthopedic surgeon, which prolonged the evaluation process from symptom onset. During the initial evaluation, the patient complained of discomfort in the lateral aspect of the left knee. He presented tenderness along the medial and lateral borders during the physical examination, a positive varus stress test, and a limited extension at 10°. No edema or crepitus during movement were appreciated. In addition, McMurray, Lachman’s, anterior drawer, posterior drawer, and patellar ballotment tests were negative. Radiographs of the left knee revealed a large, loose body at the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Anteroposterior and lateral views of the left knee showing a large, loose body over the lateral femoral condyle.

MRI shows a large osteochondral lesion involving the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle with fluid signal intensity at its base, compatible with a detached unstable OD lesion rotated 180° on its long axis (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Sagittal view of a fluid-sensitive fat-saturated T2 magnetic resonance imaging of the left knee demonstrating a large osteochondral lesion involving the posterior aspect of the lateral femoral condyle with fluid signal intensity at its base, compatible with a detached unstable osteochondral defects lesion rotated 180° on its long axis.

After discussing treatment alternatives, he opted for surgical management based on his clinical and imaging findings. Arthroscopic exploration through the anteromedial and anterolateral portals confirmed the MRI findings. The defect, measuring approximately 4.5 cm × 1.5 cm (i.e., 20.3 cm2 × 2.3 cm2), was approximated using an arthroscopic probe with a 5-mm wide tip, and inverted 180× in the sagittal plane over the lateral femoral condyle (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Intraoperative images demonstrating the fixed defect, measuring approximately 4.5 cm × 1.5 cm, and inverted 180° in the sagittal plane over the lateral femoral condyle.

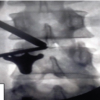

The donor autograft fractured cartilage defect was fully debrided with the shaver, while the recipient site was freshened with the shaver to achieve a clean and viable surface for fixation. Later, microfracture technique was used to enhance the healing potential of the osteochondral fragment. The fragment was reduced and pressed against the recipient site with guidewires for temporary fixation. Then, three additional guide wires were placed perpendicular to the fracture line and after verifying the guidewire direction with fluoroscopy, we drilled the cortex of the fragment and inserted the compression screws. The internal fixation was performed using three Acutrak 3.5 mm Headless Compression Screws (Acumed, Oregon, United States). Anatomical reduction was confirmed through intraoperative arthroscopic examination and intraoperative radiography (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Anatomical reduction of the osteochondral defect using three headless compression screws confirmed through intraoperative radiography.

No abnormalities of the cruciate ligaments, menisci, or patella were noted during the evaluation. The patient was discharged the same day without complications. The surgeon advised the patient to use a hinged-knee brace for the 1st-month post-surgery, gave instructions to limit weight-bearing with a gradual increase over subsequent months, and scheduled visits with an outpatient physical therapist. At his first follow-up, he experienced minor pain while ambulating and reported a complete resolution of symptoms at the 3-month visit. At the 2-year follow-up visit, the radiographs revealed proper OD healing (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Anteroposterior and lateral X-rays of the left knee showing a properly healed fragment with three headless compression screws.

The surgeon recommended the removal of hardware; however, the patient was happy with his results and opted for no further surgery fearing detriments in his excellent clinical outcomes.

We described a unique case of a young healthy male with an OD of the left knee following recreational swimming, effectively managed with ARIF. The outcomes highlight the innovative role of a minimally invasive approach for managing atraumatic large chondral lesions. While recreational swimming is considered a low-impact activity, instances like these often stem from trauma, chronic repetitive strain, or conditions such as osteochondritis dissecans [22,23]. Patellar dislocations also pose a risk, potentially causing fractures when the patella impacts the lateral femoral condyle [24,25]. The description of large ODs occurring in atraumatic settings is poorly described in the literature, potentially leading to a delayed diagnosis due to low clinical suspicion with young patients presenting with knee pain. The pre-operative radiographs showed a full-thickness cartilage defect with subchondral bone involvement, representing a sizeable loose body, consistent with a Grade 4 of the International Cartilage Repair Society classification system, a validated and reliable tool for diagnosing the depth of cartilage lesions [26,27]. While radiographs are the initial imaging diagnostic test for assessing such injuries, MRI is the gold standard modality [23,28]. In our case, MRI findings concurred with arthroscopic findings, showing a large osteochondral fragment inverted 180° in the sagittal plane over the lateral femoral condyle. Several knee procedures treat chondral injuries, including microfracture, platelet-rich plasma (PRP), and arthroscopic reduction and internal fixation [17]. Microfracture is a bone-marrow stimulation and is commonly used for small (<2 cm2) chondral lesions but unsuitable for large defects or those extending into the subchondral bone [29]. A review published by Elghawy et al. found that PRP may show clinical benefits in osteochondral lesions of the talus, yet the MRI findings of chondral regeneration are inconsistent [30]. Similarly, Woo et al. evaluated the use of PRP combined with microfractures for talus OCDs compared to microfracture only [31]. They found a significant difference in several patient-reported outcome measures (i.e., visual analog score and the foot and ankle ability measure scores) [31]. Yet, limited studies have extended the evaluation of PRP and autologous blood or bone as adjuvant treatment for large OCDs [32,33]. For instance, Rajeev et al. found that autologous conditioned plasma injections provide short-term clinical benefits for symptomatic OCDs of the knee [32]. Whereas Li et al. found that PRP scaffolding combined with osteochondral autograft transfer is a suitable alternative for femoral condyle full-thickness articular cartilage defects, improving the knee function and quality of life of 86% of their cohort and complete regeneration on MRI on all the included patients [33]. Yet, no consensus exists on the optimal management [34]. Factors like age, activity level, and lesion characteristics guide surgery [17]. For instance, Andriolo et al. found that patients with osteochondritis dissecans lesions larger than 1.2 cm2 or unstable lesions have poor prognosis following conservative management [35]. Studies show that arthroscopic fixation yields better outcomes than allograft transplantation [36,37]. Various fixation methods exist, such as Kirchner wires, compression screws, and bioabsorbable devices [17]. Limited studies compare these methods, but the latter two show acceptable rates of radiographic healing (82% with metal headless compression screws and 67% with bioabsorbable devices) [38,39]. In addition, Leland et al. reported excellent rates of radiographic union and improved patient-reported outcomes following internal fixation of osteochondritis dissecans [40]. Surgical fixation is also preferred over loose body extraction in cases of large fragments to avoid early-onset OA [41]. Despite delayed presentation and management, the patient had excellent outcomes. This case marks the first description of a previously healthy and young patient presenting with a large, unstable OD that occurred in an atraumatic setting managed successfully with ARIF. The clinical outcomes were excellent, and the patient regained full functionality within 3 months. Our results highlight the importance of high clinical suspicion in patients with knee pain without evident traumatic causes.

This report demonstrates the rare occurrence of a large and unstable OD of the lateral femoral condyle in an atraumatic setting. Our report demonstrates ARIF as an adequate surgical technique for these significant defects. We underline the importance of maintaining a high index of clinical suspicion for this diagnosis in young patients presenting with knee pain.

This case report emphasizes the successful management of a large, atraumatic osteochondral defect of the lateral femoral condyle in a young, healthy patient using ARIF. It highlights the importance of considering osteochondral defects in patients presenting with knee pain even in the absence of trauma and demonstrates the potential of minimally invasive techniques in achieving excellent clinical outcomes. By sharing this unique case, we aim to enhance clinical awareness into the diagnosis and treatment of similar conditions, ultimately contributing to improved patient care and outcomes in orthopedic sports medicine practices.

References

- 1. Du Y, Liu H, Yang Q, Wang S, Wang J, Ma J, et al. Selective laser sintering scaffold with hierarchical architecture and gradient composition for osteochondral repair in rabbits. Biomaterials 2017;137:37-48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Gross AE, Agnidis Z, Hutchison CR. Osteochondral defects of the talus treated with fresh osteochondral allograft transplantation. Foot Ankle Int 2001;22:385-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Grimm NL, Weiss JM, Kessler JI, Aoki SK. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee: Pathoanatomy, epidemiology, and diagnosis. Clin Sports Med 2014;33:181-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Flanigan DC, Harris JD, Trinh TQ, Siston RA, Brophy RH. Prevalence of chondral defects in athletes’ knees: A systematic review. Med Sci Sports Exerc 2010;42:1795-801. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lahm A, Erggelet C, Steinwachs M, Reichelt A. Articular and osseous lesions in recent ligament tears: Arthroscopic changes compared with magnetic resonance imaging findings. Arthroscopy 1998;14:597-604. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Houck DA, Kraeutler MJ, Belk JW, Frank RM, McCarty EC, Bravman JT. Do focal chondral defects of the knee increase the risk for progression to osteoarthritis? A review of the literature. Orthop J Sports Med 2018;6:2325967118801931. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. GBD 2019 Diseases and Injuries Collaborators. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990-2019: A systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2019. Lancet 2020;396:1204-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Yelin E, Weinstein S, King T. The burden of musculoskeletal diseases in the United States. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2016;46:259-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Orth P, Cucchiarini M, Kohn D, Madry H. Alterations of the subchondral bone in osteochondral repair–translational data and clinical evidence. Eur Cell Mater 2013;25:299-316; discussion 314-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Chilelli BJ, Cole BJ, Farr J, Lattermann C, Gomoll AH. The four most common types of knee cartilage damage encountered in practice: How and why orthopaedic surgeons manage them. Instr Course Lect 2017;66:507-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Von Engelhardt LV, Lahner M, Klussmann A, Bouillon B, Dàvid A, Haage P, et al. Arthroscopy vs. MRI for a detailed assessment of cartilage disease in osteoarthritis: Diagnostic value of MRI in clinical practice. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2010;11:75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Hjelle K, Solheim E, Strand T, Muri R, Brittberg M. Articular cartilage defects in 1,000 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy 2002;18:730-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Farr J, Cole B, Dhawan A, Kercher J, Sherman S. Clinical cartilage restoration: Evolution and overview. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2011;469:2696-705. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Curl WW, Krome J, Gordon ES, Rushing J, Smith BP, Poehling GG. Cartilage injuries: A review of 31,516 knee arthroscopies. Arthroscopy 1997;13:456-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Gold GE, Chen CA, Koo S, Hargreaves BA, Bangerter NK. Recent advances in MRI of articular cartilage. AJR Am J Roentgenol 2009;193:628-38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Braun HJ, Gold GE. Advanced MRI of articular cartilage. Imaging Med 2011;3:541-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Howell M, Liao Q, Gee CW. Surgical management of osteochondral defects of the knee: An educational review. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2021;14:60-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Kjennvold S, Randsborg PH, Jakobsen RB, Aroen A. Fixation of acute chondral fractures in adolescent knees. Cartilage 2021;13:293S-301S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Devitt BM, Bell SW, Webster KE, Feller JA, Whitehead TS. Surgical treatments of cartilage defects of the knee: Systematic review of randomised controlled trials. Knee 2017;24:508-17. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Rak Choi Y, Soo Kim B, Kim YM, Park JY, Cho JH, Cho YT, et al. Internal fixation of osteochondral lesion of the talus involving a large bone fragment. Am J Sports Med 2021;49:1031-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Husen M, Krych AJ, Stuart MJ, Milbrandt TA, Saris DB. Successful fixation of traumatic articular cartilage-only fragments in the juvenile and adolescent knee: A case series. Orthop J Sports Med 2022;10:23259671221138074. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Farmer JM, Martin DF, Boles CA, Curl WW. Chondral and osteochondral injuries. Diagnosis and management. Clin Sports Med 2001;20:299-320. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Kuhle J, Sudkamp NP, Niemeyer P. [Osteochondral fractures at the knee joint]. Unfallchirurg 2015;118:621-32; quiz 633-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Callewier A, Monsaert A, Lamraski G. Lateral femoral condyle osteochondral fracture combined to patellar dislocation: A case report. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2009;95:85-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Taitsman LA, Frank JB, Mills WJ, Barei DP, Nork SE. Osteochondral fracture of the distal lateral femoral condyle: A report of two cases. J Orthop Trauma 2006;20:358-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Dwyer T, Martin CR, Kendra R, Sermer C, Chahal J, Ogilvie-Harris D, et al. Reliability and validity of the arthroscopic international cartilage repair society classification system: Correlation with histological assessment of depth. Arthroscopy 2017;33:1219-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Biant LC, Conley CW, McNicholas MJ. The first report of the international cartilage regeneration and joint preservation society’s global registry. Cartilage 2021;13:74S-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Kao YJ, Ho J, Allen CR. Evaluation and management of osteochondral lesions of the knee. Phys Sportsmed 2011;39:60-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Kraeutler MJ, Belk JW, Purcell JM, McCarty EC. Microfracture versus autologous chondrocyte implantation for articular cartilage lesions in the knee: A systematic review of 5-year outcomes. Am J Sports Med 2018;46:995-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Elghawy AA, Sesin C, Rosselli M. Osteochondral defects of the talus with a focus on platelet-rich plasma as a potential treatment option: A review. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2018;4:e000318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Woo I, Park JJ, Seok HG. The efficacy of platelet-rich plasma augmentation in microfracture surgery osteochondral lesions of the talus: A systematic review and meta-analysis. J Clin Med 2023;12:4998. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Rajeev A, Ali M, Devalia K. Autologous conditioned plasma and hyaluronic acid injection for isolated grade 4 osteochondral lesions of the knee in young active adults. Cureus 2022;14:e27787. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 33. Li M, Tu Y, Zhang H, Zhang Y, Di Z. Effect of platelet-rich plasma scaffolding combined with osteochondral autograft transfer for full-thickness articular cartilage defects of the femoral condyle. Biomed Mater 2022 Oct 13;17(6).DOI:10.1088/1748-605X/ac976d. [Google Scholar] [PubMed] [CrossRef]

- 34. Bauer KL. Osteochondral injuries of the knee in pediatric patients. J Knee Surg 2018;31:382-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 35. Andriolo L, Candrian C, Papio T, Cavicchioli A, Perdisa F, Filardo G. Osteochondritis dissecans of the knee – conservative treatment strategies: A systematic review. Cartilage 2019;10:267-77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 36. Reilingh ML, Lambers KT, Dahmen J, Opdam KT, Kerkhoffs GM. The subchondral bone healing after fixation of an osteochondral talar defect is superior in comparison with microfracture. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2018;26:2177-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 37. Powers RT, Dowd TC, Giza E. Surgical treatment for osteochondral lesions of the talus. Arthroscopy 2021;37:3393-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 38. Millington KL, Shah JP, Dahm DL, Levy BA, Stuart MJ. Bioabsorbable fixation of unstable osteochondritis dissecans lesions. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:2065-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 39. Barrett I, King AH, Riester S, Van Wijnen A, Levy BA, Stuart MJ, et al. Internal fixation of unstable osteochondritis dissecans in the skeletally mature knee with metal screws. Cartilage 2016;7:157-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 40. Leland DP, Bernard CD, Camp CL, Nakamura N, Saris DB, Krych AJ. Does internal fixation for unstable osteochondritis dissecans of the skeletally mature knee work? A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2019;35:2512-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 41. Sanders TL, Pareek A, Obey MR, Johnson NR, Carey JL, Stuart MJ, et al. High rate of osteoarthritis after osteochondritis dissecans fragment excision compared with surgical restoration at a mean 16-year follow-up. Am J Sports Med 2017;45:1799-805. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]