Although arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer combined with superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) in patients with posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears resulted in clinical improvement at the 5-year follow-up, the risk of SCR graft rupture should be carefully considered when performing this combined procedure.

Dr. Chang Hee Baek, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Yeosu Baek Hospital, Yeosu, Republic of Korea. E-mail: yeosubaek@gamail.com

Introduction: Given the distinct biomechanical advantages of superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) and arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer (aLTT), aLTT combined with SCR may synergistically restore both static and dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint, leading to superior functional outcomes compared to either procedure alone. This case report demonstrated the clinical and radiologic outcomes of aLTT combined with SCR in patients with posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears (PSIRCTs).

Case Report: A total of three patients with PSIRCTS were treated with aLTT combined with SCR. The mean age was 58.0 ± 6.1 years, and all patients were male. Mean follow-up periods were 66.0 ± 5.0 months. Three patients showed improvement in clinical outcomes, including Visual Analog Scale score, patient-reported outcome measurements, and active range of motion. However, progression to Hamada grade 4 arthritic changes was observed in one patient, and SCR graft rupture was confirmed in all three patients.

Conclusion: aLTT combined with SCR in patients with PSIRCTs resulted in clinical improvement at the 5-year follow-up; however, SCR graft rupture was observed. This may be due to stress concentration on the graft, which could have contributed to the failure. Therefore, the risk of SCR graft rupture should be carefully considered when performing this combined procedure.

Keywords: Posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears, lower trapezius tendon transfer, superior capsular reconstruction.

Posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears (PSIRCTs) involve the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons, which are essential for forward elevation (FE) and external rotation (ER) of the shoulder [1]. These tears can significantly disrupt the coronal and transverse plane force couples of the glenohumeral joint, resulting in joint instability, muscle weakness, and substantial functional limitations, particularly in FE and ER [2]. Managing PSIRCTs remains challenging due to the loss of dynamic stabilizers, imbalance of force couples, and poor potential for tendon healing or functional recovery [3]. Joint-preserving treatment options include arthroscopic debridement, partial repair, biceps tenotomy or tenodesis, subacromial balloon spacer insertion, superior capsular reconstruction (SCR), and tendon transfers [4,5,6,7,8]. SCR aims to restore the superior stability of the glenohumeral joint by reconstructing the superior capsule, thereby preventing proximal migration of the humeral head [7]. Biomechanically, SCR restores the static stabilizing effect of the superior capsule, acting as a spacer that re-centers the humeral head and restores the fulcrum for deltoid function [9]. Clinical studies have reported favorable outcomes with improved pain relief and shoulder function, particularly in carefully selected patients [10]. However, SCR alone does not provide dynamic stability, and its success is highly dependent on the integrity of the remaining rotator cuff muscles, especially the infraspinatus [11]. In patients with poor infraspinatus quality or function, clinical outcomes tend to be less predictable, and the risk of graft retear or failure increases significantly [12].

Arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer (aLTT) has emerged as a promising joint-preserving surgical option for PSIRCTs [13]. Biomechanically, the lower trapezius (LT) exhibits a line of pull that closely resembles that of the native infraspinatus, making it an ideal substitute for restoring ER [14]. LTT provides dynamic stability through active muscle contraction, contributing to the restoration of the transverse force couple and improving shoulder function, including active range of motion (aROM) and high rates of patient satisfaction [11]. However, aLTT alone does not provide a static superior stabilizing structure and thus may be insufficient to prevent superior migration of the humeral head [15]. Given the distinct biomechanical advantages and limitations of SCR and aLTT, combining these two procedures may synergistically restore both static and dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint, leading to superior functional outcomes compared to either procedure alone. This case report demonstrated the clinical and radiologic outcomes of aLTT combined with SCR in patients with PSIRCTs.

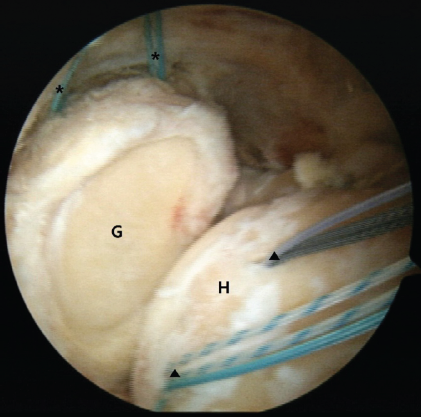

This case report demonstrated the three patients who underwent aLTT combined with SCR for PSIRCTs between 2018 and 2019 (minimum 5 years follow-up). The criteria used to diagnose PSIRCTs included: (1) extensive rotator cuff tears involving both the supraspinatus and infraspinatus tendons; (2) substantial tendon retraction and shortening to the level of the glenoid, corresponding to Patte stage III on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI); (3) advanced fatty degeneration in the affected tendons, classified as Goutallier grade 3 or 4; (4) a structurally preserved or reparable subscapularis tendon with Goutallier grade 2 or lower; and (5) intraoperative confirmation that tendon mobilization was insufficient to allow reattachment to the humeral head footprint, even after thorough soft tissue release. The surgical indications for aLTT combined with SCR for PSIRCTs were: (1) symptomatic cases marked by persistent shoulder pain and functional impairment impacting daily life; (2) failure to achieve improvement through conservative therapy for a minimum of 6 months; (3) minimal or early-stage glenohumeral arthritis (Hamada grade I or II); and (4) absence of neurological impairments or infectious conditions (Fig. 1).

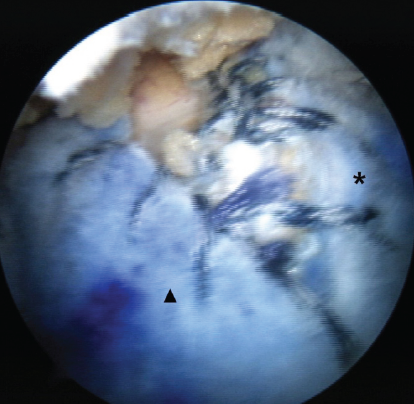

Figure 1: Intraoperative arthroscopy image of posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears of the right shoulder. Due to extensive rotator cuff tears involving the supraspinatus and infraspinatus, there was substantial tendon retraction and shortening to the level of the glenoid, making reattachment to the humeral head footprint unfeasible even after thorough soft tissue release. Two 4.5-mm polyether ether ketone (PEEK) Corkscrew (asterisk) anchors were inserted into the superior glenoid, and two additional 4.5-mm PEEK (arrowhead) Corkscrew anchors were placed into the supraspinatus footprint. G: glenoid; H: humeral head.

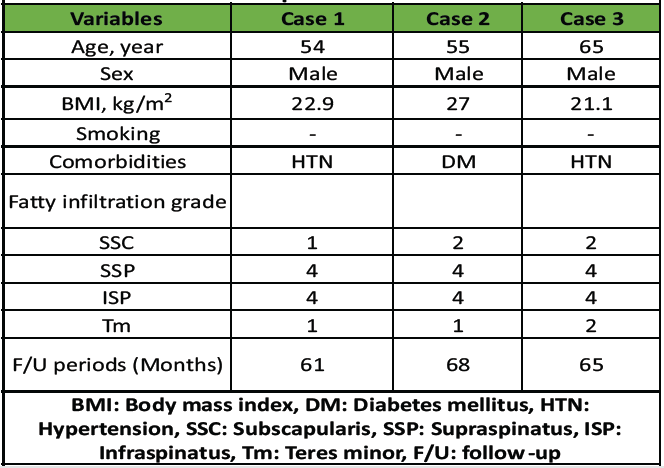

Clinical outcomes were assessed by Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score, patient-reported outcome measurements (PROMs), and aROM. Radiological outcomes were evaluated by the acromiohumeral distance (AHD) and progression of osteoarthritic change. All clinical and radiological outcomes were compared between the pre-operative evaluation and the final follow-up evaluation. A total of three patients were treated with aLTT combined with SCR for PSIRCTs. The mean age was 58.0 ± 6.1 years, and all patients were male. Mean follow-up periods were 66.0 ± 5.0 months. The demographic characteristics are described in Table 1.

Table 1: Demographic and clinical characteristics of patients

In detailed surgical techniques, the lateral decubitus position and general anesthesia were used to prepare the patients. During the diagnostic examination with arthroscopy, the feasibility of repairing the supraspinatus and infraspinatus was assessed. The condition of the subscapularis and the long head of the biceps tendon was first assessed. Subsequently, SCR was carried out following the technique described by Mihata et al. A fascia lata autograft, including the intermuscular septum attached to the gluteus maximus, was harvested to ensure adequate thickness. The graft was folded 3–4 times to achieve a minimum thickness of 6 mm. The superior glenoid rim and the greater tuberosity footprint were decorticated to prepare for graft fixation. Two 4.5-mm PEEK Corkscrew anchors were inserted into the superior glenoid, and another two were placed at the supraspinatus footprint. The medial side of the graft was fixed using a mattress suture configuration, whereas the lateral aspect was secured with a double-row suture bridge technique, performed with the arm positioned in 30° of abduction (Fig. 1). The medial edge of the graft was secured using a mattress suture technique, while the lateral edge was affixed using the double-row suture bridge technique with lateral anchors in the shoulder at a 30° abduction position. After that, the LT tendon was harvested for aLTT. A skin incision approximately 5 cm in length was made along the scapular spine, extending from its medial border. The boundary between the LT tendon and the middle trapezius (MT) tendon was identified, and the LT tendon was separated from the MT tendon. A small incision was made in the infraspinatus fascia to provide a pathway for transferring the LT tendon. Then, the Achilles tendon allograft was folded 2 or 3 times to achieve a minimum thickness of 6 mm, a width of 2 cm, and a length of 15 cm, serving as an interpositional graft. One medial row anchor was inserted into the infraspinatus footprint. The interpositional graft was passed through the infraspinatus fascia into the subacromial space. After being placed on the infraspinatus footprint, the graft was fixed using medial-row and lateral-row anchors. The interpositional graft was connected to the SCR graft with a side-to-side suturing technique (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Intraoperative arthroscopy image of arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer (aLTT) combined with superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) of the right shoulder. The SCR graft (asterisk) was attached to the supraspinatus footprint, and the interpositional graft (arrowhead) of aLTT was attached to the infraspinatus footprint. The interpositional graft was connected to the SCR graft with a side-to-side suturing technique.

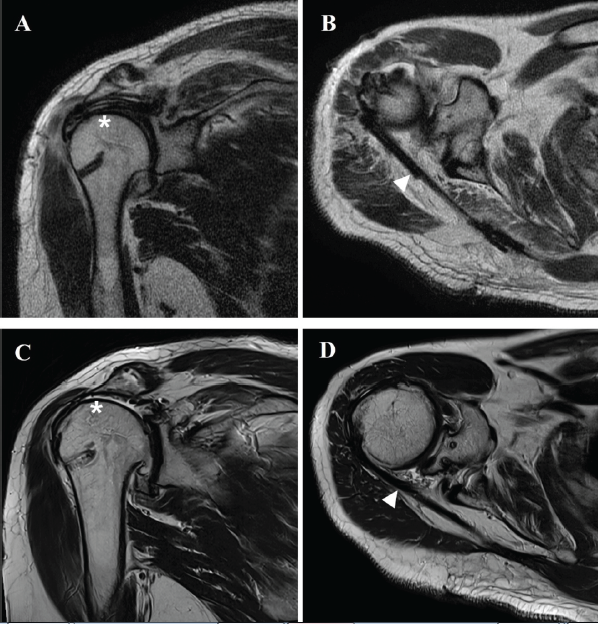

Finally, the interpositional graft was sutured to the LT tendon using the Krackow technique. Postoperatively, the operated arm was immobilized in a 30° abduction shoulder brace for 6 weeks to protect both the reconstructed superior capsule and the transferred tendon. Passive ROM exercises were initiated after brace removal, focusing initially on FE and ER within pain-free limits. When full passive ROM was achieved—typically 8–10 weeks after surgery—active-assisted and active ROM exercises were progressively introduced under physiotherapist supervision. Strengthening exercises were started around 12–14 weeks postoperatively, emphasizing gradual scapulothoracic coordination and controlled eccentric loading. Heavy lifting, resistance training, and overhead activities were restricted for at least 6 months to prevent excessive tension on the graft and allow maturation of the tendon–graft–bone interface. Return to light daily activities was generally permitted at 3 months, and full return to functional activity at 6–8 months postoperatively, depending on patient tolerance and recovery progression. All patients showed improvement in clinical outcomes. The post-operative mean VAS score (2.3 ± 0.6) was improved compared to pre-operative mean VAS score (6.3 ± 0.6). The Constant–Murley score (40.3 ± 2.1 to 70.7 ± 2.5), American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons score (43.7 ± 3.5 to 65.0 ± 2.6), and activities of daily living requiring ER score (42.3 ± 2.5 to 60.7 ± 8.4) showed improvement after aLTT combined with SCR. Among the aROM (FE, 93.3 ± 11.5 to 133.3 ± 25.2), abduction (ABD, 90.0 ± 17.3 to 120.0 ± 26.5), and (ER, 6.7 ± 5.8 to 35.0 ± 8.7) also showed significant improvement after operation. As a radiologic outcome, the AHD showed no changes before and after the operation. In one of the three patients, the Hamada grade progressed from grade 1 preoperatively to grade 4 postoperatively (Table 2). In all three patients, the interpositional graft of the aLTT was well maintained on the final follow-up MRI, whereas a rupture of the SCR graft was observed (Fig. 3). There was no post-operative complication.

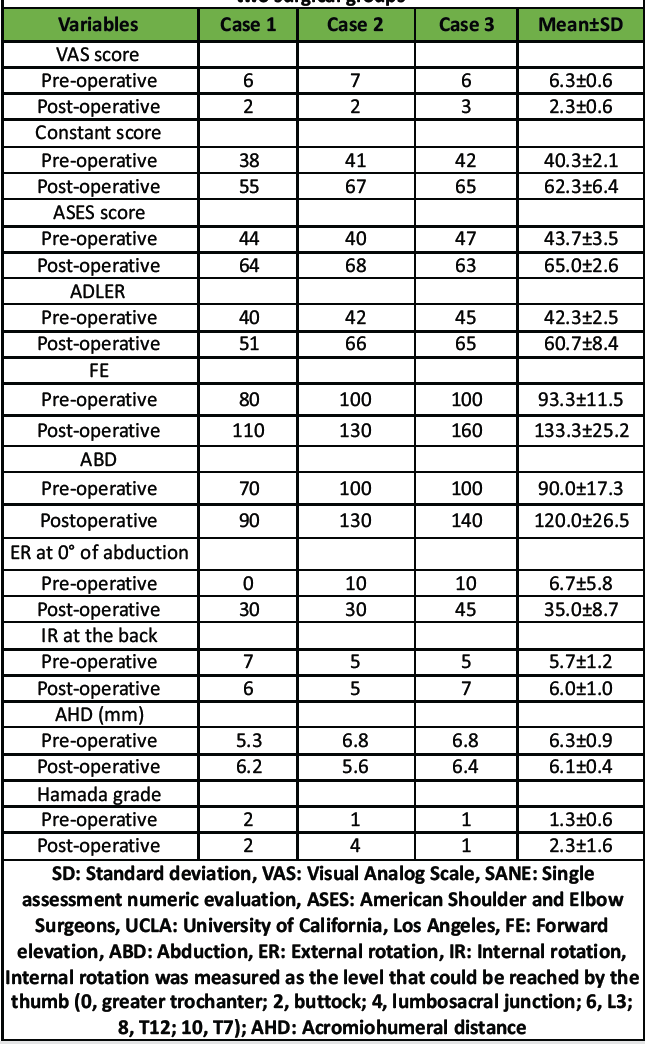

Table 2: Comparisons of clinical and functional outcomes between the two surgical groups

Figure 3: Post-operative magnetic resonance image (MRI) of arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer (aLTT) combined with superior capsular reconstruction (SCR) of the right shoulder. T2-weighted coronal (a) and axial (b) image of immediate post-operative MRI showing well-fixed SCR graft (asterisk) and interpositional graft of aLTT (arrowhead). T2-weighted coronal (c) and axial (d) image of immediate post-operative 5-year MRI showing rupture of SCR graft (asterisk) and well-maintained interpositional graft of aLTT (arrowhead).

This case report is meaningful in that it presents a rare clinical outcome of aLTT combined with SCR in PSIRCTs. To our knowledge, only two biomechanical studies and one case report on this combined procedure have been published to date. In this case report, all three patients showed improvement in clinical outcomes, including VAS score, PROMs, and aROM. However, one patient showed progression of arthritic changes, and all three patients demonstrated rupture of the SCR graft. Based on these results, aLTT combined with SCR may lead to improved clinical outcomes over more than 5 years of follow-up in PSIRCTs; however, the risk of SCR graft rupture should be considered, and efforts to promote graft healing are essential. In PSIRCTs, chronic rupture of the supraspinatus and infraspinatus significantly disrupts the coronal and transverse plane force couples of the glenohumeral joint [2]. Therefore, the restoration of both static and dynamic stabilizers of the glenohumeral joint is essential to reestablish the coronal and transverse plane force couples in PSIRCTs [3]. As a promising joint-preserving surgical option for PSIRCTs, SCR and aLTT demonstrated a favorable clinical outcome [10,13]. However, SCR alone does not provide dynamic stability, and its success is highly dependent on the integrity of the remaining rotator cuff muscles, especially the infraspinatus [12]. aLTT alone does not provide a static superior stabilizing structure and thus may be insufficient to prevent superior migration of the humeral head [15]. Therefore, in accordance with the “one tendon–one function” principle of tendon transfer [16], aLTT combined with SCR may synergistically restore both static and dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint, leading to superior functional outcomes compared to either procedure alone. Two biomechanical studies on LTT combined with SCR in PSIRCTs have been reported [15,17]. Lee et al. reported that SCR combined with LTT significantly decreased superior migration and subacromial peak pressure compared with LTT alone or SCR alone in fresh-frozen cadaveric shoulder. Thus, the combination of SCR and LTT may have an advantage for additional stability [15]. Moreover, Amirouche et al. demonstrated that LTT with SCR led to superior restoration of teres major and subscapularis forces relative to single techniques, indicating that this combination more effectively reestablished native rotator cuff biomechanics than either technique alone [17]. To date, only a single case report has described the clinical outcomes of aLTT combined with SCR. McCormick et al. reported the case of SCR with LTT in a 49-year-old male patient with PSIRCTs. They demonstrated that the combination of LTT and SCR may represent a valuable treatment strategy for PSIRCTs in younger patients. While SCR is more effective for alleviating pain and improving FE, the addition of LTT may better restore ER function [18]. However, they did not report on the status of the SCR graft or the interpositional graft of the aLTT. In line with previous biomechanical studies, we hypothesized that aLTT combined with SCR may synergistically restore both static and dynamic stability of the glenohumeral joint, thereby resulting in superior functional outcomes compared to either procedure performed alone. However, although all three patients showed improvement in clinical outcomes, all patients demonstrated rupture of the SCR graft. The stress concentration on the graft of SCR may be a contributing factor of these ruptures [11]. With both ends of the graft fixed to the SSP footprint and glenoid side, the shoulder ROM, such as abduction, could result in a stretched and deformed graft due to the high stress concentration. This graft creep phenomenon (graft gets stretched and deformed) may lead to SCR graft failure [19]. The static stability restored by the reconstruction of the superior capsule could be deteriorated by the graft creep [11]. Therefore, when performing aLTT in combination with SCR, the risk of SCR graft rupture should be taken into consideration. However, further large sample-sized clinical research is required to confirm these findings. This study has several limitations. First, it is a small case report including only three patients, which precludes any statistical analysis and limits the generalizability of the findings. Second, the absence of a control group, such as SCR or aLTT alone, prevents comparative evaluation of the combined procedure. Third, all operations were performed at a single institution by one experienced surgeon, which, although ensuring procedural consistency, may introduce technique-related bias. Fourth, while all cases were followed for more than 5 years, interim quantitative assessments were limited, and serial biomechanical data such as graft creep or dynamic humeral head migration were not available. Finally, functional evaluation was confined to basic outcome measures, and post-operative rehabilitation adherence could not be objectively verified. Nevertheless, despite these limitations, this case report provides valuable long-term observations of consistent graft rupture of SCR after aLTT and SCR, suggesting potential mechanical stress factors and the need for future biomechanical and comparative investigations.

aLTT combined with SCR in patients with PSIRCTs resulted in clinical improvement at the 5-year follow-up; however, SCR graft rupture was observed. This may be due to stress concentration on the graft, which could have contributed to the failure. Therefore, the risk of SCR graft rupture should be carefully considered when performing this combined procedure.

Although aLTT combined with SCR in patients with PSIRCTs resulted in clinical improvement at the 5-year follow-up, the risk of SCR graft rupture should be carefully considered when performing this combined procedure.

References

- 1. Collin P, Matsumura N, Lädermann A, Denard PJ, Walch G. Relationship between massive chronic rotator cuff tear pattern and loss of active shoulder range of motion. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23:1195-202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Baek CH, Lim C, Kim JG, Kim BT, Kim SJ. Preoperative external rotation lag sign doesn’t diminish the efficacy of arthroscopy-assisted lower trapezius tendon transfer in posterosuperior irreparable rotator tears. J Orthop 2025;67:27-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Carver TJ, Kraeutler MJ, Smith JR, Bravman JT, McCarty EC. Nonarthroplasty surgical treatment options for massive, irreparable rotator cuff tears. Orthop J Sports Med 2018;6:2325967118805385. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kovacevic D, Suriani RJ Jr., Grawe BM, Yian EH, Gilotra MN, Hasan SA, et al. Management of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears: A systematic review and meta-analysis of patient-reported outcomes, reoperation rates, and treatment response. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2020;29:2459-75. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kim YS, Lee HJ, Park I, Sung GY, Kim DJ, Kim JH. Arthroscopic in situ superior capsular reconstruction using the long head of the biceps tendon. Arthrosc Tech 2018;7:e97-103. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Vecchini E, Gulmini M, Peluso A, Fasoli G, Anselmi A, Maluta T, et al. The treatment of irreparable massive rotator cuff tears with inspace balloon: Rational and medium-term results. Acta Biomed 2021;92 Suppl 3:e2021584. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Watanabe C, Fukunishi K, Ohue M, Tsujimura T, et al. Clinical results of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. Arthroscopy 2013;29:459-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Baek CH, Lee DH, Kim JG. Latissimus dorsi transfer vs. Lower trapezius transfer for posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2022;31:1810-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Mihata T, McGarry MH, Pirolo JM, Kinoshita M, Lee TQ. Superior capsule reconstruction to restore superior stability in irreparable rotator cuff tears: A biomechanical cadaveric study. Am J Sports Med 2012;40:2248-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Mihata T, Lee TQ, Hasegawa A, Fukunishi K, Kawakami T, Fujisawa Y, et al. Five-year follow-up of arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019;101:1921-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Baek CH, Lim C, Kim JG. Superior capsular reconstruction versus lower trapezius transfer for posterosuperior irreparable rotator cuff tears with high-grade fatty infiltration in the infraspinatus. Am J Sports Med 2022;50:1938-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Lim S, AlRamadhan H, Kwak JM, Hong H, Jeon IH. Graft tears after arthroscopic superior capsule reconstruction (ASCR): Pattern of failure and its correlation with clinical outcome. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2019;139:231-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Baek CH, Kim BT, Kim JG, Kim SJ. Mid-term outcome of superior capsular reconstruction using fascia lata autograft (at least 6 mm in thickness) results in high retear rate and no improvement in muscle strength. Arthroscopy 2024;40:1961-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Omid R, Lee B. Tendon transfers for irreparable rotator cuff tears. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2013;21:492-501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Lee JB, Kholinne E, Ben H, So SP, Alsaqri H, Koh KH, et al. Superior capsular reconstruction combined with lower trapezius tendon transfer improves the biomechanics in posterosuperior massive rotator cuff tears. Am J Sports Med 2023;51:3817-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Wilbur D, Hammert WC. Principles of tendon transfer. Hand Clin 2016;32:283-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Amirouche F, Mungalpara N, Kim S, Lee C, Chen K, Baker H, et al. Restoration of rotator cuff muscle forces in lower trapezius transfer and superior capsular reconstruction in massive rotator cuff tear. JSES Int 2025;9:1532-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. McCormick JR, Menendez ME, Hodakowski AJ, Garrigues GE. Superior capsule reconstruction and lower trapezius transfer for irreparable posterior-superior rotator cuff tear: A case report. JBJS Case Connect 2022;12:e22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Ding S, Ge Y, Zheng M, Ding W, Jin W, Li J, et al. Arthroscopic superior capsular reconstruction using singing gerior rotator cuff tear: A case report. JBJS Case Connecte Connectnnectse 2022;8:e953-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]