In matched THA patients, aspirin prophylaxis produced lower 1-year VTE rates than LMWH without a significant rise in major bleeding; supporting guideline-endorsed use of aspirin as an effective, pragmatic option for typical-risk patients.

Dr. Aamir Shahzad, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Trust, Manchester, United Kingdom. E-mail: amirshehzad4321@gmail.com

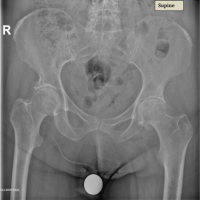

Introduction: Total hip arthroplasty (THA) carries a persistent risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE). Contemporary guidelines endorse combined mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis often extended to 35 days post-operative; yet the optimal agent remains debated as evidence comparing aspirin with low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) is mixed (e.g., EPCAT II vs. CRISTAL).

Materials and Methods: We conducted a retrospective, propensity-matched cohort study using the TriNetX Network. Adults undergoing primary THA were assigned to mutually exclusive cohorts based on initial post-operative chemoprophylaxis within 7 days: Aspirin (no LMWH exposure in days 0–7) or LMWH (no aspirin exposure in days 0–7). Outcomes were assessed from post-operative day 1 to day 365. One-to-one propensity score matching balanced age, sex, race/ethnicity, body mass index, hypertension, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, diabetes, obesity, and metabolic disorders. Effect measures included risk difference (RD) with two-sided P (primary; also applied to risk ratio [RR] per protocol), (RR, 95% confidence interval [CI]), and hazard ratio (HR) from Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank P. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05. Guideline context is provided for interpretability.

Results: After matching (aspirin n = 8,559; LMWH n = 8,559), 1-year outcomes favored aspirin for thromboembolism. Any VTE: 1.7% versus 2.6%; RR = 0.649 (0.525–0.803), P < 0.001; and HR = 0.635, P = 0.475. Deep vein thrombosis: 1.4% versus 2.3%; RR = 0.610 (0.485–0.769), P < 0.001; and HR = 0.598, P = 0.142. Pulmonary embolism (PE): 0.6% versus 1.0%; RR = 0.665 (0.472–0.935), P = 0.018; and HR = 0.651, P = 0.603. Major bleeding: 11.1% versus 10.2%; RR = 1.089 (0.999–1.188), P = 0.053; and HR = 1.094, P = 0.001. Minor bleeding: 2.2% versus 2.1%; RR = 1.050 (0.858–1.284), P = 0.637; and HR = 1.029, P = 0.969. Emergency department visit: 13.6% versus 18.7%; RR = 0.727 (0.679–0.780), P < 0.001; and HR = 0.694, P = 0.463. Findings align with guidance permitting aspirin as prophylaxis in appropriately selected arthroplasty patients, while acknowledging randomized evidence favoring LMWH in some settings.

Conclusions: In matched THA patients, aspirin achieved lower 1-year VTE than LMWH with no statistically significant increase in major bleeding by RD. Given trial heterogeneity (e.g., CRISTAL versus meta-analyses and step-down strategies), agent selection should be individualized, balancing thrombotic and bleeding risks, logistics, and patient preference within guideline-concordant, extended prophylaxis pathways (Two-sided significance threshold: P < 0.05).

Keywords: Lmwh, THA, Aspirin, VTE, Bleeding Risk

Total hip arthroplasty (THA) carries a significant risk of venous thromboembolism (VTE), including deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE). Without appropriate prophylaxis, historical studies reported alarmingly high PE rates after THA, making VTE a major cause of post-operative mortality [1,2]. Modern guidelines therefore universally recommend combined mechanical and pharmacologic prophylaxis for THA patients, typically extending anticoagulant therapy for up to 35 days postoperatively [1,3]. Low-molecular-weight heparin (LMWH) has long been a standard prophylaxis due to its proven efficacy in reducing VTE incidence. However, LMWH administration is parenteral, costly, and associated with bleeding and hematoma risks. In recent years, aspirin has gained popularity as an alternative VTE prophylactic agent after joint arthroplasty, due to its low cost, oral administration, and favorable safety profile. Clinical evidence has suggested that aspirin can be as effective as more intensive anticoagulation in preventing post-operative VTE [4,5,6]. For example, some studies have found aspirin to be non-inferior to LMWH or other anticoagulants in reducing VTE after THA or total knee arthroplasty (TKA) [6,7]. As a result, contemporary guidelines include aspirin among recommended chemoprophylaxis options for orthopedic patients [3,4,5]. Despite aspirin’s advantages and increasing use, the optimal choice of prophylaxis for THA remains debated. Findings from recent trials and meta-analyses have been conflicting. On one hand, certain large randomized studies have indicated that aspirin may be less effective than LMWH in this setting. Notably, the 2022 CRISTAL randomized trial reported a significantly higher 90-day symptomatic VTE rate in THA/TKA patients receiving aspirin compared to those receiving enoxaparin (3.45% vs. 1.82%) [8]. Similarly, a recent systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized trials found no overall difference in total VTE risk between aspirin and LMWH, but did observe a higher risk of PE with aspirin prophylaxis (odds ratio ~1.8, P = 0.017) [9]. On the other hand, observational data from large arthroplasty cohorts have shown no increase in VTE with aspirin – and even suggested lower thrombosis rates with aspirin in some instances. For example, a multi-center study of high-risk arthroplasty patients found that more “potent” anticoagulation did not reduce VTE compared with aspirin [10], and contemporary comparative analyses report similar or lower bleeding with aspirin than with other agents [11]. These divergent results highlight the uncertainty in real-world prophylaxis effectiveness. There is concern that differences in patient risk factors and prophylaxis practices (e.g., patient selection for aspirin vs. LMWH) could explain the inconsistent findings. Therefore, further investigation using large-scale, real-world data is warranted to compare outcomes between aspirin and LMWH prophylaxis after THA.

Objective

The aim of this study was to compare the incidence of post-operative VTE and major bleeding events between aspirin and LMWH prophylaxis in patients undergoing THA. We utilized a large multicenter electronic health records network and propensity score matching (PSM) to balance baseline characteristics. We hypothesized that aspirin would provide VTE protection comparable to LMWH without a significant increase in bleeding complications.

Study design and data source

We performed a retrospective comparative cohort study using the TriNetX Network (multicenter EHR data). In this query, 71 healthcare organizations were queried.

Population and cohort definitions

Adults undergoing THA were identified using procedural codes contained in the platform’s THA concept set. Two mutually exclusive post-operative thromboprophylaxis cohorts were defined:

Aspirin cohort: THA plus aspirin (using RxNorm Codes) within 7 days on or after THA, with no LMWH exposure in the first 7 days.

LMWH cohort: THA plus LMWH; enoxaparin , dalteparin, and tinzaparin within 7 days on or after THA, with no aspirin exposure in the first 7 days.

The index event was the first qualifying THA; the index date for analysis was the first qualifying prophylaxis exposure (aspirin or LMWH) within the 7-day post-operative window. TriNetX limits index-event ascertainment to events up to 20 years before the analysis window.

Outcomes and follow-up: Variables, data sources/measurement

Outcomes were assessed from post-operative day 1 through day 365 after the index date, excluding patients who had the outcome before the analysis window. Outcomes were reported individually and categorized as:

Thromboembolic: Any VTE (composite of DVT/PE), DVT, and PE

Bleeding: Major bleeding events and minor bleeding events

Healthcare utilization: Emergency department (ED) visit.

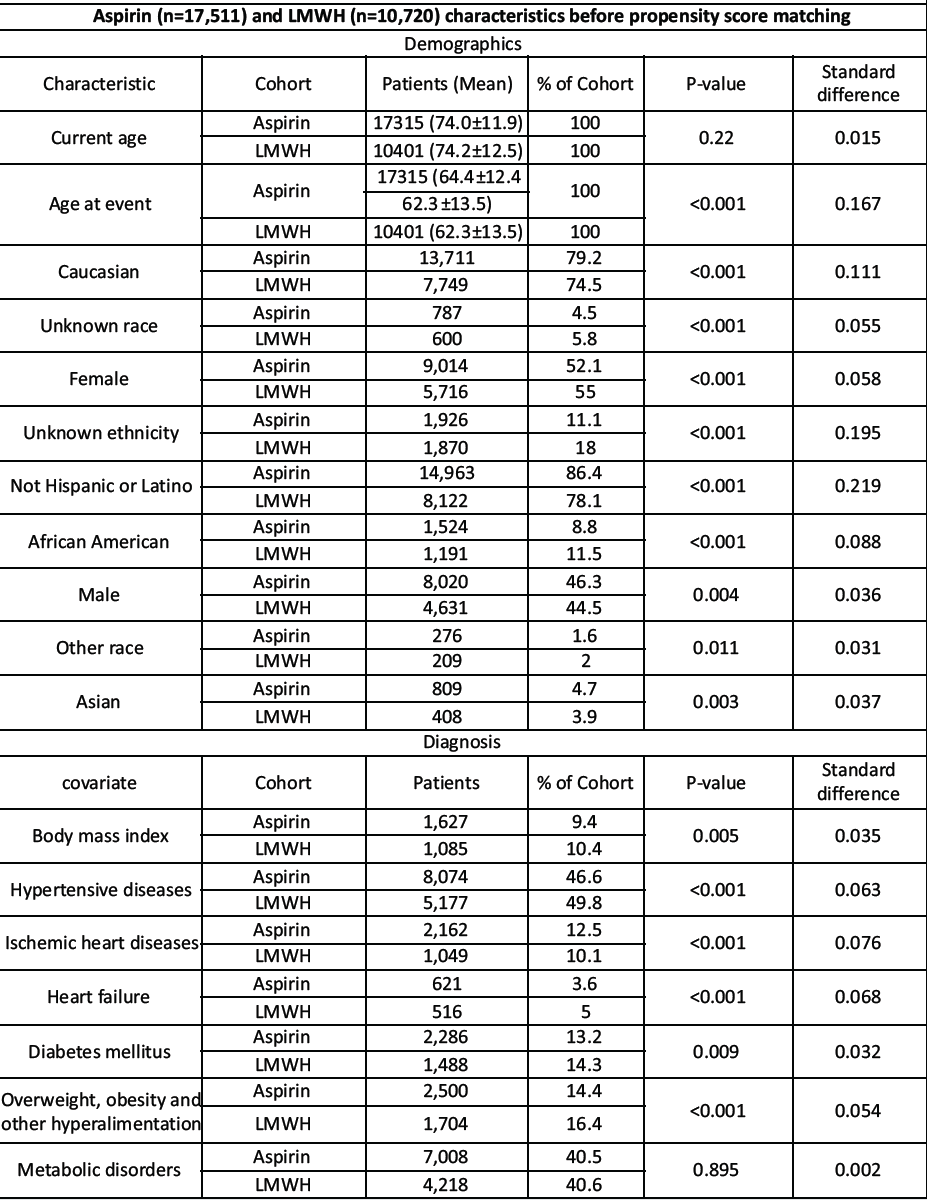

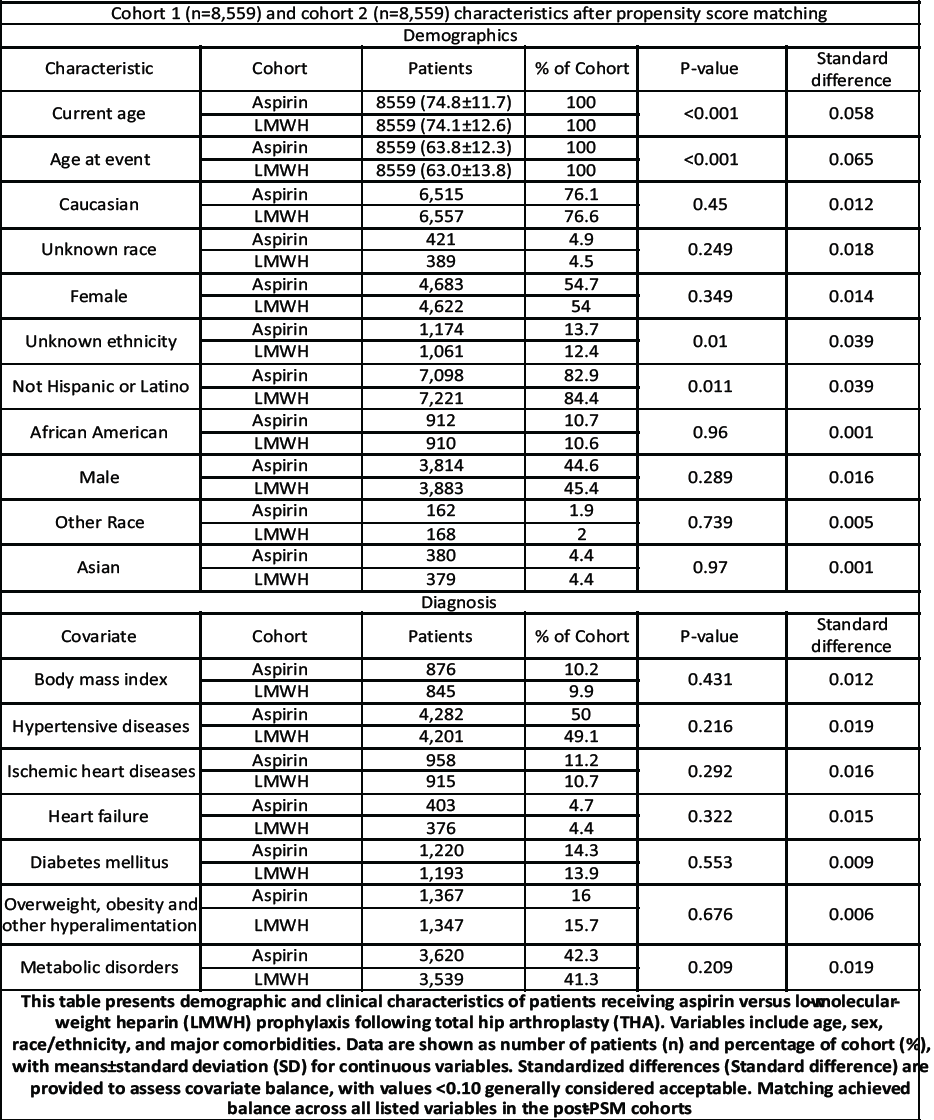

PSM

Cohorts were matched 1:1 using propensity scores to balance baseline characteristics. Covariates (as listed in your matched characteristics table) included age at index, race/ethnicity categories (e.g., Caucasian, african American, Asian etc.), body mass index , and comorbidities such as hypertensive diseases, ischemic heart disease, heart failure, diabetes mellitus, overweight/obesity, and other metabolic disorders. Balance was evaluated in the matched sample (Table 1).

Table 1: Cohort characteristic and PSM

Statistical analysis

For each outcome, we report risk difference (RD) with 95% confidence interval (CI) and P-value (primary; per protocol, this P also applies to risk ratio [RR]), (RR, 95% CI), and Hazard ratio (HR) from Kaplan–Meier analysis with log-rank P. All tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Follow-up time (mean, standard deviation [SD]; median, interquartile range [IQR]) is reported after matching. All analyses were executed within TriNetX with default settings for risk and survival analyses.

Cohorts and follow-up

Before matching, cohort sizes were Aspirin n = 17,511 and LMWH n = 10,720. After 1:1 PSM, the matched cohorts comprised Aspirin n = 8,559 and LMWH n = 8,559 (Table 1 for demographics and covariate balance).

Follow-up after matching: Mean (SD) Aspirin 340.8 (81.7) days, LMWH 332.4 (93.5) days; median 365 days for both (IQR 0 for both), indicating near-complete 1-year capture.

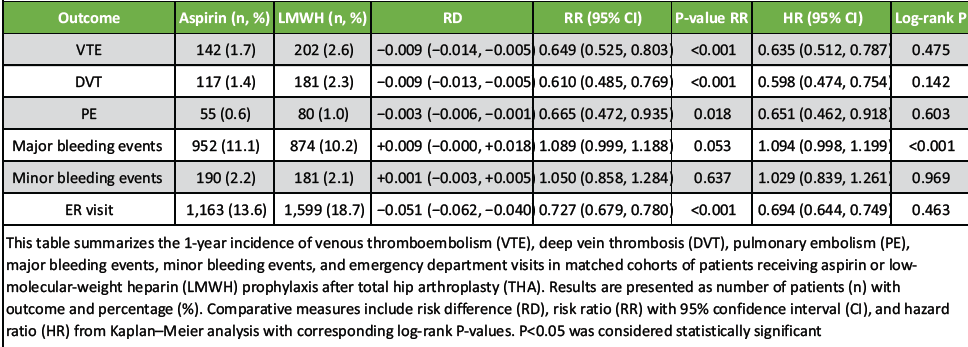

Outcomes

All outcomes below are 1-year incidences, with effect estimates shown as RD, RR (95% CI), and HR (95% CI); RR p equals the RD P-value; HR p is the log-rank p. Full numeric details appear in Table 2.

Thromboembolic outcomes

Any VTE: 1.7% (Aspirin) versus 2.6% (LMWH); RD = −0.009 (−0.014, −0.005), P = 0.000; RR = 0.649 (0.525–0.803); and HR = 0.635 (0.512–0.787), log-rank P = 0.475 (Table 2).

DVT: 1.4% versus 2.3%; RD = −0.009 (−0.013, −0.005), P = 0.000; RR = 0.610 (0.485–0.769); and HR = 0.598 (0.474–0.754), log-rank P = 0.142 (Table 2).

PE: 0.6% versus 1.0%; RD = −0.003 (−0.006, −0.001), P = 0.018; RR = 0.665 (0.472–0.935); and HR = 0.651 (0.462–0.918), log-rank P = 0.603 (Table 2).

Bleeding outcomes

- Major bleeding events: 11.1% versus 10.2%; RD = +0.009 (−0.000, +0.018), P = 0.053; RR = 1.089 (0.999–1.188); and HR = 1.094 (0.998–1.199), log-rank P = 0.000 (Table 2).

- Minor bleeding events: 2.2% versus 2.1%; RD = +0.001 (−0.003, +0.005), P = 0.637; RR = 1.050 (0.858–1.284); and HR = 1.029 (0.839–1.261), log-rank P = 0.969 (Table 2).

Healthcare utilization

- ED visit: 13.6% versus 18.7%; RD = −0.051 (−0.062, −0.040), P = 0.000; RR = 0.727 (0.679–0.780); and HR = 0.694 (0.644–0.749), log-rank P = 0.463 (Table 2).

Interpretation

In matched THA patients, aspirin was associated with lower VTE, DVT, and PE risks than LMWH at 1 year. Major bleeding was slightly higher by RD but borderline by RD P; survival analysis showed a significant log-rank P for major bleeding. ED visits were lower with aspirin. Table 2 for full estimates.

Table 2: One-year outcomes after THA by prophylaxis (Aspirin vs. LMWH)

Key results

In this retrospective cohort study of THA patients, we found that post-operative aspirin prophylaxis was associated with at least equivalent, and potentially superior, protection against VTE compared to LMWH. After PSM, the cumulative 1-year incidence of any VTE was significantly lower in the aspirin group (1.7%) than in the LMWH group (2.6%). This difference translated to a RR of approximately 0.65 in favor of aspirin, with a 95% CI excluding unity. The reduction in VTE risk with aspirin was observed for both components of the composite outcome: The aspirin cohort had lower rates of DVT (1.4% vs. 2.3% in LMWH) and PE (0.6% vs. 1.0% in LMWH) during follow-up. These results met our study objective in demonstrating non-inferiority of aspirin and, in fact, suggested a possible relative risk reduction in thromboembolic events. In terms of safety outcomes, the incidence of major bleeding events was similar between groups. The aspirin-treated patients had a slightly higher 1-year cumulative incidence of major bleeding (11.1% vs. 10.2% with LMWH), but this difference was not statistically significant. Thus, our data indicate that an aspirin-based prophylactic strategy did not incur a meaningful penalty in bleeding risk while preventing thromboembolic events at least as effectively as the standard LMWH regimen [6,7,11,12,13].

Interpretation of findings

Our findings must be interpreted in the context of existing literature, which, as noted, has reported mixed results on the efficacy of aspirin versus LMWH for thromboprophylaxis in arthroplasty. Notably, our real-world results contrast with the recent CRISTAL randomized trial, which found aspirin to be inferior to enoxaparin. In CRISTAL, aspirin failed to meet non-inferiority and was associated with nearly double the rate of symptomatic VTE compared to LMWH (3.45% vs. 1.82% within 90 days) [8,12]. That high-quality trial, along with recent meta-analytic data, suggests that LMWH provides more effective VTE prevention than aspirin under rigorous clinical trial conditions [9,14]. At first glance, our observational data showing fewer thromboembolic events with aspirin might appear contradictory. However, several considerations can reconcile these differences. First, patient selection and residual confounding likely play a role. In routine practice, surgeons often risk-stratify patients when choosing prophylaxis. It is possible that healthier patients with lower intrinsic VTE risk (younger, fewer comorbidities) were more likely to receive aspirin, whereas higher-risk patients (e.g., obesity, prior VTE, and hypercoagulable states) were preferentially given LMWH. Despite our PSM on available covariates, such unmeasured risk factors could bias results in favor of aspirin. This phenomenon has been noted by prior authors–more “potent” anticoagulants are often reserved for perceived high-risk cases, yet real-world data have not always shown improved outcomes in those patients [10,15,16]. Thus, our study supports the notion that aspirin can be as effective as LMWH in typical THA populations, when patients are appropriately selected. It is important to acknowledge, however, that our findings do not necessarily contradict the randomized controlled trial (RCT) evidence, because differences in patient populations and adherence could be at play. Second, differences in perioperative protocols and adjunct measures may influence outcomes. All patients in our cohorts underwent standard mechanical prophylaxis (compression devices and early mobilization) as is routine in modern practice. High compliance with these measures, combined with shorter hospital stays and aggressive rehabilitation (“fast-track” protocols), can lower overall VTE incidence for all patients. It is conceivable that, under such optimized protocols, the marginal benefit of LMWH over aspirin is diminished. Our matched cohorts had median hospital follow-up of 1 year, but details such as duration of prophylaxis were not captured. We assume most patients received prophylaxis for several weeks post-op as per guideline recommendations [1,3]. If aspirin patients tended to continue prophylaxis for a full 4–6 weeks (due to ease of oral administration), whereas some LMWH patients might have received shorter courses (since injectable LMWH is often stopped early if transitioning to oral agents or due to adherence issues), this could partly explain fewer VTEs in the aspirin group. Unfortunately, our data source did not detail the exact duration of therapy or transitions to other anticoagulants. Notably, randomized evidence supports the role of extended prophylaxis with aspirin after an initial short course of a direct oral anticoagulant (DOAC) [7,13]. Third, our results align with the growing body of evidence suggesting aspirin’s efficacy in low-risk arthroplasty patients. Multiple recent studies have concluded that for standard-risk patients, aspirin prophylaxis yields VTE outcomes comparable to more intensive anticoagulants, while reducing bleeding and wound complications [6,11,15]. Some experts now consider aspirin an acceptable first-line prophylaxis in many primary joint arthroplasties. Indeed, a 2022 international consensus group recommended low-dose aspirin as a reasonable and safe option for the general total joint population [4]. Our findings provide real-world outcome data that support this perspective: We observed no compromise in patient safety (no excess PE or mortality signals in the aspirin group) alongside potentially favorable secondary benefits. It is worth noting that our analysis also showed no significant difference in major bleeding rates between the two cohorts. This is an important finding, as one purported advantage of aspirin is its lower risk of bleeding complications compared to anticoagulants. In our matched population, the rates of major bleeding were roughly 10–11% in both groups. The slightly higher rate observed with aspirin (0.9% absolute difference) did not reach statistical significance. These results mirror those of prior studies, including meta-analyses, which have generally found no significant difference in major bleeding between aspirin and LMWH prophylaxis [6,9]. It is possible that aspirin’s bleeding advantage is more pronounced for minor bleeds rather than the severe bleeding events captured here. Alternatively, patient and surgical factors (e.g., use of tranexamic acid) might have overshadowed any pharmacologic differences in bleeding risk in our cohorts. Nonetheless, the comparable bleeding outcomes provide reassurance that switching to aspirin prophylaxis is unlikely to expose THA patients to substantially greater hemorrhagic risk in exchange for thrombosis prevention.

Generalizability

Our study leveraged a large federated real-world dataset spanning many hospital organizations, which enhances the external validity of the findings. The included patients represent a broad cross-section of THA recipients in the United States, including various ages, comorbidities, and practice settings. Therefore, the results should be generalizable to contemporary practice in similar healthcare systems where both aspirin and LMWH are routinely used for post-operative thromboprophylaxis. In particular, our data support the use of aspirin in standard-risk elective THA patients. The outcomes observed in this group low overall VTE incidence (~2%) and no excess harms with aspirin are encouraging and in line with contemporary real-world and trial-adjacent benchmarks [2,11]. It is also notable that symptomatic PE rates we observed were comparable to controlled-trial estimates [8]. Our findings may not extend to very high-risk patients (prior VTE, thrombophilia, active cancer, complex revisions), who were likely under-represented or preferentially treated with LMWH. However, caution is warranted in extrapolating our results to all patient populations. The generalizability may be limited for high-risk subsets such as patients with prior VTE, known thrombophilia, cancer, or those undergoing revision or bilateral surgeries. Such patients were included in our analysis, but they might have been preferentially assigned to LMWH in real practice, as suggested by baseline RDs before matching. Therefore, while aspirin performed well on average, one should be careful applying this strategy to very high-risk individuals without individualized risk assessment. In healthcare settings outside of large academic or network hospitals, the patterns of prophylaxis use might differ (e.g., centers favoring DOACs). Our study did not include direct DOAC comparisons; however, randomized data support aspirin as non-inferior to rivaroxaban for extended prophylaxis following an initial short DOAC course [7,15].

Limitations

This study has several important limitations. First, as an observational analysis drawn from electronic health records, residual confounding is a concern. Despite PSM, residual confounding and confounding by indication cannot be eliminated. Surgeons may have preferentially prescribed aspirin to lower-risk patients, which could bias results in favor of aspirin. Second, the database lacked reliable information on the exact dose, duration, or adherence to aspirin or LMWH. Differences in prophylaxis length, early discontinuation, or step-down transitions to aspirin may have influenced both VTE and bleeding outcomes. Third, reliance on administrative coding and EHR documentation may have led to under-reporting or misclassification of VTE or bleeding events, which could bias the risk estimates despite the large sample size. Fourth, we did not compare DOACs directly, although RCT data inform step-down strategies [7]. Finally, our findings differ from the cluster-randomized CRISTAL trial favoring LMWH at 90 days [8], unlike randomized trials such as CRISTAL, our observational analysis cannot establish causality. Without randomization or external validation, the apparent superiority of aspirin must be interpreted cautiously and does not definitively change clinical practice guidelines.

In a large propensity-matched THA cohort, aspirin prophylaxis achieved lower 1-year VTE than LMWH without a statistically significant increase in major bleeding. These real-world results, considered alongside mixed trial and meta-analytic evidence, support aspirin as a viable first-line option for many typical-risk THA patients, particularly where extended, patient-adherent prophylaxis is emphasized. For higher-risk profiles, LMWH (or a DOAC) remains appropriate, and shared decision-making should incorporate patient factors, bleeding risk, logistics, and evolving guideline recommendations.

In matched THA patients, aspirin prophylaxis produced lower 1-year VTE rates than LMWH without a significant rise in major bleeding; supporting guideline-endorsed use of aspirin as an effective, pragmatic option for typical-risk patients.

References

- 1. Falck-Ytter Y, Francis CW, Johanson NA, Curley C, Dahl OE, Schulman S, et al. Prevention of VTE in orthopedic surgery patients: Antithrombotic therapy and prevention of thrombosis, 9th ed: American college of chest physicians evidence-based clinical practice guidelines. Chest 2012;141(2 Suppl):e278S-325. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. White RH, Zhou H, Romano PS, Rodrigo J, Bargar W. Incidence and time course of thromboembolic outcomes following total hip or knee arthroplasty. Arch Intern Med 1998;158:1525-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Anderson DR, Morgano GP, Bennett C, Dentali F, Francis CW, Garcia DA, et al. American Society of Hematology 2019 guidelines for management of venous thromboembolism: Prevention of venous thromboembolism in surgical hospitalized patients. Blood Adv 2019;3:3898-944. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. ICM-VTE Hip & Knee Delegates. Recommendations from the ICM-VTE: Hip and Knee. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2022;104(Suppl 1):180-231. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Uzel K, Azboy İ, Parvizi J. Venous thromboembolism in orthopedic surgery: Global guidelines. Acta Orthop Traumatol Turc 2023;57:192-203. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Matharu GS, Kunutsor SK, Judge A, Blom AW, Whitehouse MR. Clinical effectiveness and safety of aspirin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after total hip and knee replacement: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized clinical trials. JAMA Intern Med 2020;180:376-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Anderson DR, Dunbar M, Murnaghan J, Kahn SR, Gross P, Bohm E, et al. Aspirin or rivaroxaban for VTE prophylaxis after hip or knee arthroplasty. N Engl J Med 2018;378:699-707. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. CRISTAL Study Group, Sidhu VS, Kelly TL, Pratt N, Graves SE, Buchbinder R, et al. Effect of aspirin vs enoxaparin on symptomatic venous thromboembolism in patients undergoing hip or knee arthroplasty: The CRISTAL randomized trial. JAMA 2022;328:719-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Salman LA, Altahtamouni SB, Khatkar H, Al-Ani A, Hameed S, Alvand A. The efficacy of aspirin versus low-molecular-weight heparin for venous thromboembolism prophylaxis after knee and hip arthroplasty: A systematic review and meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2025;33:1605-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Tan TL, Foltz C, Huang R, Chen AF, Higuera C, Siqueira M, et al. Potent anticoagulation does not reduce venous thromboembolism in high-risk patients. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2019;101:589-99. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Simon SJ, Patell R, Zwicher JI, Kazi DS, Hollenbeck BL. Venous thromboembolism in total hip and total knee arthroplasty. JAMA Netw Open 2023;6:e2345883. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Shafiei SH, Riazi M, Jafarian AH, Rahmani P, Moradi A, Khajeh A, et al. Low-dose vs high-dose aspirin after arthroplasty: Similar VTE and adverse events. Clin Orthop Surg. 2023;15:241–249. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Eikelboom JW, Quinlan DJ, Douketis JD. Extended-duration prophylaxis against venous thromboembolism after total hip or knee replacement: A meta-analysis of the randomised trials. Lancet 2001;358:9-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Heckmann ND, Austin DC, Mayfield CK, Li J, Chen AF, Springer BD, et al. Aspirin for VTE prophylaxis following TKA/THA: Narrative synthesis. J Arthroplasty. 2023;38:2152–2160. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Wong DW, Lee QJ, Lo CK, Law KW, Wong DH. Incidence of venous thromboembolism after primary total hip arthroplasty with mechanical prophylaxis in Hong Kong Chinese. Hip Pelvis 2024;36:108-19. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Jones A, Wootton A, Kakkos S, Patel R, Nguyen T, Al-Obaidi M, et al. VTE prophylaxis in major lower-extremity orthopedic procedures: Contemporary review. J Clin Med. 2023;12:4968. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]