MUA and ACR yield comparable long-term outcomes in frozen shoulder; MUA allows early recovery while ACR provides safer release under visualization.

Dr. Anuraag Mohanty, Department of Orthopaedics, Kalinga Institute of Medical Sciences (KIMS), Bhubaneswar, Odisha, India. E-mail: anuraag98@gmail.com

Introduction: Adhesive capsulitis, commonly known as frozen shoulder (FS), is a disabling condition marked by progressive restriction in shoulder mobility and pain. It is frequently linked with metabolic disorders such as diabetes and thyroid dysfunction. While many patients respond favorably to conservative therapies, a proportion remains unresponsive and requires surgical intervention.

Materials and Methods: This prospective, randomized study was conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics at Jajati Kesari Medical College and Hospital, Jajpur, Odisha, from March 02, 2023, to March 02, 2024. A total of 30 patients (16 females, 14 males; aged 45–65 years) diagnosed with primary refractory FS were enrolled. All patients underwent pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging to validate the diagnosis and rule out any coexisting pathology. Participants were randomly assigned into two groups using a computer-generated sequence: Group 1 underwent Manipulation Under Anesthesia (MUA) (n = 15; 10 diabetic, 5 non-diabetic), and Group 2 underwent Arthroscopic Capsular Release (ACR) (n = 15; 12 diabetic, 3 non-diabetic). Clinical outcomes were assessed using the Visual Analog Scale for pain, the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons and Constant scores for shoulder function, and measurements of range of motion (ROM), including abduction, forward flexion, external rotation, and internal rotation. Assessments were performed at baseline, 1 week, 3 months, 6 months, and 1-year post-intervention.

Results: Both MUA and ACR produced significant improvements in pain, ROM, and functional scores over the follow-up period. Although the MUA group demonstrated slightly faster early gains, long-term outcomes were comparable between groups. Notably, complications were observed in the MUA group (three cases: mild capsular tear, labral tear, and rotator cuff tendinitis) compared with one minor complication (bone bruising) in the ACR group.

Conclusion: Both MUA and ACR are effective in improving pain, ROM, and shoulder function in patients with refractory FS. With similar long-term outcomes, MUA’s simplicity and cost-effectiveness support its role as a first-line intervention, while the controlled release offered by ACR may be advantageous in select cases. Further large-scale studies are warranted to optimize treatment protocols.

Keywords: Frozen shoulder, manipulation under anesthesia, arthroscopic capsular release, range of motion, diabetes, prospective randomized study.

Frozen shoulder (FS) is characterized by progressive pain, stiffness, and a substantial loss of shoulder range of motion (ROM) [1]. It is most frequently observed in individuals between 40 and 65 years, with a higher prevalence in women, and is commonly associated with systemic conditions such as diabetes mellitus and thyroid dysfunction. Although the condition may eventually resolve over 12–18 months [2], the prolonged pain and functional impairment significantly affect patients’ quality of life and daily activities. The pathogenesis involves an early inflammatory phase [3] with synovitis and capsular edema, followed by a fibrotic phase in which excessive collagen deposition leads to capsular contracture. While conservative management (including non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, corticosteroid injections, and structured physiotherapy) [4] results in improvement in most patients, approximately 10–20% of cases remain refractory. In such patients, surgical options become necessary. Manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) and arthroscopic capsular release (ACR) are the two primary surgical interventions [5] for refractory FS. MUA is valued for its cost-effectiveness and simplicity; however, it is performed as a blind procedure that may inadvertently injure adjacent structures. In contrast, ACR allows for direct visualization and precise capsular release, potentially reducing soft-tissue injury. Although several studies report similar long-term outcomes [6] between MUA and ACR, controversy remains regarding their relative safety profiles and cost-effectiveness. This study prospectively compares these two techniques, with subgroup analysis based on diabetic status, to provide further evidence on their clinical efficacy.

Study design and setting

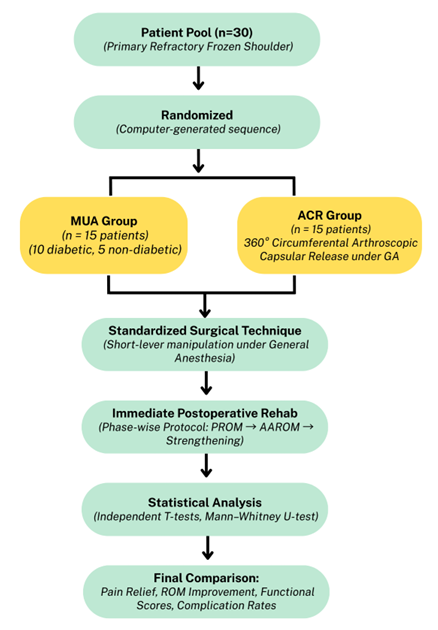

This prospective, randomized study was conducted in the Department of Orthopaedics at Jajati Kesari Medical College and Hospital, Jajpur, Odisha, over a 1-year period from March 02, 2023, to March 02, 2024. Ethical approval for the study was granted by the Institutional Ethics Committee, and written informed consent was secured from all participants before their inclusion in the study. The complete workflow can be seen in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Study design comparing manipulation under anesthesia and arthroscopic capsular release in frozen shoulder patients with randomization, intervention, and outcome assessment.

Patient selection and randomization

Thirty patients with refractory primary FS were enrolled based on the following criteria:

Inclusion criteria

- Age 45–65 years

- Clinical diagnosis of primary FS with both active and passive ROM restriction (forward elevation <100° and external rotation <50% of the contralateral side)

- Failure to improve with a minimum of six months of conservative management.

Exclusion criteria

- Secondary shoulder stiffness due to trauma, infection, or inflammatory arthritis

- Previous shoulder surgery

- Concomitant rotator cuff tears or other significant shoulder pathology.

Patients were randomized using a computer-generated sequence into two groups:

- MUA Group: 15 patients (10 diabetic, 5 non-diabetic)

- ACR Group: 15 patients (12 diabetic, 3 non-diabetic).

The overall cohort consisted of 16 females and 14 males.

Allocation was concealed using sequentially numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes prepared by an independent coordinator. Surgeons and physiotherapists were necessarily unblinded; outcome assessors remained blinded to group assignment throughout follow-up.

Pre-operative investigations

All patients underwent pre-operative Magnetic Resonance Imaging to confirm the diagnosis of primary adhesive capsulitis and to rule out secondary intra-articular or periarticular pathologies. Metabolic evaluation included measurement of fasting blood sugar glucose, postprandial blood sugar glucose, glycated hemoglobin, and thyroid function tests to assess glycemic control and endocrine status.

Surgical techniques

MUA

Patients received short-duration general anesthesia (GA) and were positioned supine. A standardized short-lever manipulation was performed by sequentially moving the shoulder through flexion, abduction, and rotation (Fig. 2). Emphasis was placed on external rotation followed by cross-chest adduction to release inferior adhesions, with the release confirmed by audible tearing sounds. Patients were instructed to commence passive range-of-motion (PROM) exercises immediately on recovery to maintain intraoperative gains.

Figure 2: Short lever manipulation sequence for refractory frozen shoulder.

ACR

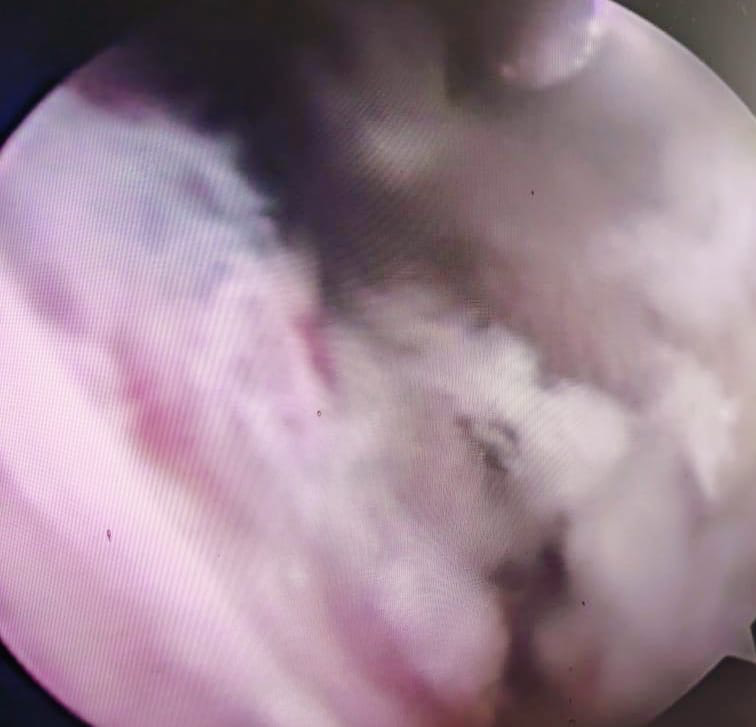

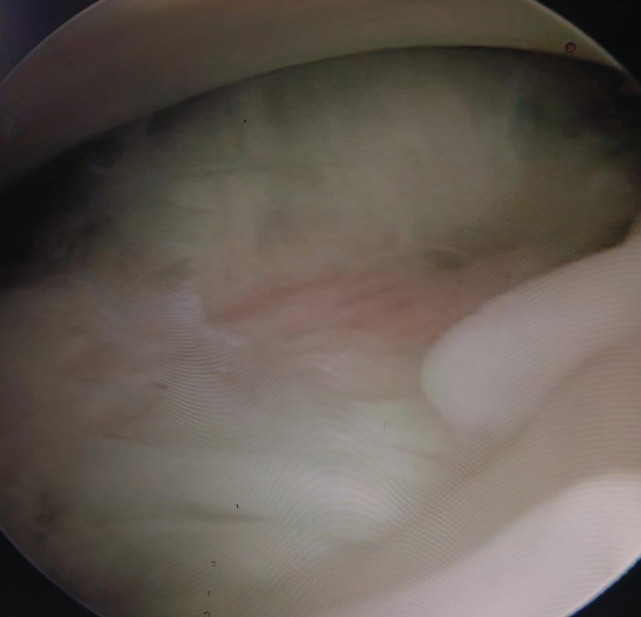

Patients in the ACR group were similarly induced with short-duration GA and positioned supine. Diagnostic arthroscopy was performed via a posterior portal to avoid cartilage injury. Under direct visualization, a 360° circumferential release was performed by sequentially releasing the rotator interval, coracohumeral ligament, and middle glenohumeral ligament, followed by release of the anterior, posterior, and inferior capsules (Figs. 3 and 4). Early mobilization exercises were initiated within 24 h postoperatively (Fig. 5).

Figure 3: Inflamed rotator interval targeted for arthroscopic release in frozen shoulder.

Figure 4: Fibrotic bridging across the anterior capsule in refractory frozen shoulder.

Figure 5: Posterior capsule after partial release in refractory frozen shoulder.

All procedures were performed by the same senior orthopedic surgeon to maintain consistency in surgical technique and intraoperative decision-making.

Post-operative rehabilitation protocol

A standardized post-operative rehabilitation protocol was implemented for both groups with adjustments based on the surgical technique:

- For the MUA Group:

- Immediate Phase (0–2 weeks): Patients begin PROM exercises as soon as they recover from anesthesia. This includes gentle pendulum exercises and assisted PROM under physiotherapist supervision to maintain the intraoperative release

- Early Rehabilitation (2–6 weeks): Transition to active assisted range-of-motion exercises focusing on forward flexion, abduction, and both external and internal rotation. Scapular stabilization exercises are introduced to support coordinated shoulder movement

- Strengthening Phase (6–12 weeks and beyond): Progressive resistance exercises are initiated to restore muscle strength and endurance, coupled with continued stretching to preserve ROM

- For the ACR Group:

- Immediate Phase (0–24 h): Controlled PROM exercises are initiated within 24 h postoperatively, reflecting the precision of the arthroscopic release

- Early Rehabilitation (1–6 weeks): Patients progress to active assisted exercises with gradual emphasis on achieving full ROM. Exercises include gentle stretching, scapular stabilization, and coordinated active-assisted movements in all planes.

- Strengthening Phase (6–12 weeks and beyond): A structured strengthening program is introduced to enhance rotator cuff and scapular muscle function, with continued focus on ROM maintenance.

Both groups received daily supervised physiotherapy sessions during the initial 6 weeks, which were then gradually tapered based on individual progress. Patients were also instructed to perform home-based exercises to ensure continuity of rehabilitation.

Outcome measures and statistical analysis

The following outcome measures were evaluated:

- Pain: Assessed using the Visual Analog Scale (VAS)

- Function: Measured through the American Shoulder and Elbow Surgeons (ASES) scoring system and the Constant score

- ROM: Quantified in terms of abduction, forward flexion, external rotation, and internal rotation using a goniometer.

Evaluations were conducted preoperatively and postoperatively at intervals of 1 week, three months, 6 months, and 1 year. Statistical comparisons were made using independent T-tests and Mann–Whitney U-tests. Additional subgroup analysis was carried out based on diabetes status. A P-value below 0.05 was considered indicative of statistical significance.

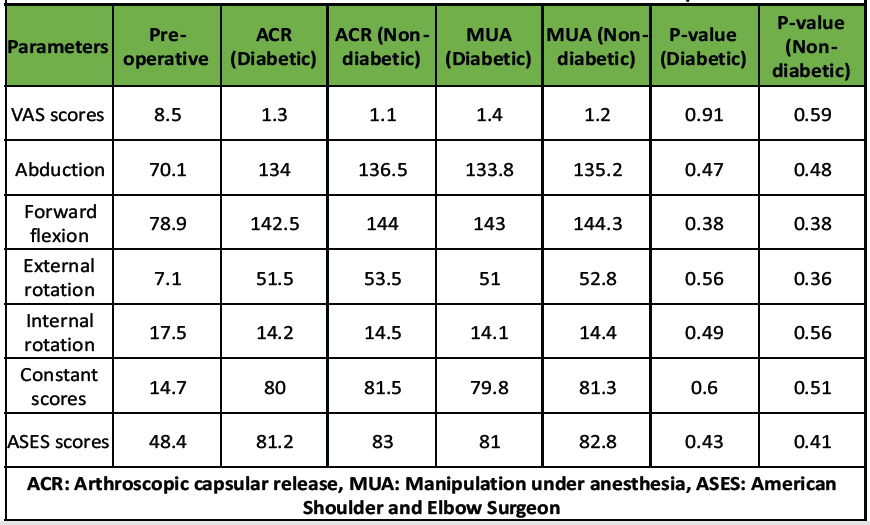

Thirty patients were randomized equally into the MUA and ACR groups. Baseline assessments revealed a mean VAS score of 8.5, limited abduction (70.1°), restricted forward flexion (78.9°), reduced external rotation (7.1°), and poor Constant and ASES scores (14.7 and 48.4, respectively). At the final follow-up, both groups demonstrated substantial improvements in pain relief, ROM, and functional outcomes. In the ACR group, diabetic patients (n = 12) achieved a mean VAS score of 1.3, abduction of 134.0°, forward flexion of 142.5°, and Constant and ASES scores of 80.0 and 81.2, respectively. Non-diabetic patients (n = 3) in the ACR group exhibited slightly superior outcomes, with a VAS of 1.1, abduction of 136.5°, forward flexion of 144.0°, and Constant and ASES scores of 81.5 and 83.0. Similarly, in the MUA group, diabetic patients (n = 10) reached a mean VAS of 1.4, abduction of 133.8°, forward flexion of 143.0°, and Constant and ASES scores of 79.8 and 81.0. Non-diabetics (n = 5) in the MUA group achieved marginally better outcomes, with a VAS of 1.2, abduction of 135.2°, forward flexion of 144.3°, and Constant and ASES scores of 81.3 and 82.8. ROM parameters improved significantly across all subgroups. In terms of external rotation, ACR diabetics achieved a mean of 51.5° while non-diabetics reached 53.5°, compared to 51.0° and 52.8° in the MUA diabetic and non-diabetic groups, respectively. Internal rotation was similarly restored across all cohorts, with means ranging between 14.1° and 14.5°. Subgroup analysis revealed that non-diabetic patients consistently achieved slightly better outcomes than diabetic patients within both treatment arms. However, none of these differences reached statistical significance. The P-values for ACR vs MUA comparisons in diabetics and non-diabetics were >0.05 across all measured parameters, including VAS (P = 0.91 and 0.59), abduction (P = 0.47 and 0.48), forward flexion (P = 0.38 and 0.38), external rotation (P = 0.56 and 0.36), internal rotation (P = 0.49 and 0.56), Constant score (P = 0.60 and 0.51), and ASES score (P = 0.43 and 0.41). Detailed summary values for pain, range of motion, Constant, and ASES scores at baseline and final follow-up are provided in Table 1.

Table 1: ROM and outcome scores table at final follow-up

These findings confirm that both MUA and ACR are equally effective in restoring shoulder function in patients with FS, with no statistically significant differences in outcomes across surgical modality or diabetic status. Regarding complications, the MUA group experienced three minor events a mild capsular tear, a labral tear, and rotator cuff tendinitis, while the ACR group had one minor case of bone bruising. All complications were managed conservatively and did not affect long-term outcomes.

Our study confirms that both MUA and ACR are effective surgical interventions for refractory primary FS, with significant improvements in pain, ROM, and functional outcomes observed in both groups [7,8]. These findings are in line with earlier randomized studies, which reported similar long-term efficacy for both procedures [9,10]. Early post-operative assessments in our study indicated that MUA may provide slightly faster pain relief and ROM recovery [11,12]; however, by 6 months and 1 year, outcome differences between MUA and ACR had become negligible. This aligns with observations from the FROST trial [13], which emphasized that although early gains may differ, long-term functional outcomes converge. Although adherence to physiotherapy was encouraged and monitored during the initial supervised phase, individual compliance was not objectively quantified. This reflects the practical limitations of real-world follow-up but may contribute to variability in functional recovery. Subgroup analysis based on diabetic status revealed that diabetic patients in both groups demonstrated marginally reduced improvements compared to non-diabetics [12], though these differences were not statistically significant. Similar observations have been documented by Pandey and Madi (2021) and Kivimäki et al. (2007) attributed reduced outcomes in diabetic patients to abnormal collagen metabolism and impaired tissue healing. From a safety perspective, our data revealed that the MUA group experienced three minor complications [13], including mild capsular tear, labral tear, and rotator cuff tendinitis, while the ACR group reported only one minor complication (bone bruising). Although the sample size was small, these findings suggest that the controlled and visually guided nature of ACR may reduce the risk of inadvertent soft-tissue injury. This is supported by studies such as those by Grant et al. (2013) and Kim et al. (2020), which found a lower incidence of procedural complications with ACR due to the advantage of direct intra-articular visualization. The uniform surgical technique, rehabilitation protocol, and follow-up methodology in our single-center study contributed to minimizing confounding variables and enhancing internal consistency. However, further multicenter trials are needed to validate the generalizability of our findings. Cost-effectiveness and accessibility are also key considerations when comparing the two techniques [14]. MUA remains a favorable first-line option in many settings due to its low cost, procedural simplicity, and feasibility in outpatient environments. These benefits have been corroborated by previous cost-analysis reports [15]. However, ACR, although more resource-intensive, provides precision and safety advantages, especially in complex or high-risk cases. While diabetes is a known confounding factor in FS, our subgroup analysis still demonstrated consistent outcome trends across both diabetic and non-diabetic cohorts. The findings suggest that despite minor differences, the comparative efficacy between MUA and ACR holds true across metabolic backgrounds. This study has certain limitations. The relatively small sample size limits generalizability and reduces the power to detect minor intergroup differences. Although the 1-year follow-up adequately reflects short- and mid-term recovery, it may not capture long-term outcomes or recurrence. Being a single-center study, external validity remains limited, and some performance bias may persist despite randomization. While subgroup analysis for diabetic status was performed, specific parameters such as duration of diabetes and glycemic control were not consistently recorded. A formal cost-effectiveness analysis was not conducted, and only narrative comparison of resource use was made. Post-operative imaging was not routinely performed in asymptomatic patients, consistent with local practice, and outcomes were primarily assessed clinically. Larger multicentric studies with longer follow-up, structured economic assessment, and objective imaging would provide more comprehensive evidence. Future multicenter, large-scale trials with extended follow-up are essential to validate these findings, refine patient selection criteria, and further delineate the role of MUA and ACR across diverse patient populations.

In conclusion, both MUA and ACR are effective in enhancing shoulder mobility, alleviating pain, and improving function in individuals with persistent primary FS. Given their similar long-term outcomes, MUA remains a viable first-line surgical intervention due to its cost-efficiency and procedural simplicity. Although ACR allows for a more controlled release and may reduce the likelihood of soft-tissue injury, its clinical results are generally comparable. Further multicenter research with expanded sample sizes is essential to better determine the most effective surgical strategy across diverse patient groups.

Both MUA and ACR are effective surgical options for refractory FS. While MUA is quicker and more economical, ACR offers a controlled, visually guided approach with potentially fewer complications. The choice should be tailored to the patient’s clinical profile and resource setting.

References

- 1. Brealey S, Armstrong AL, Brooksbank A, Carr AJ, Charalambous CP, Cooper C, et al. United Kingdom Frozen Shoulder Trial (UK FROST), multi-centre, randomised, 12 month, parallel group, superiority study to compare the clinical and cost-effectiveness of Early Structured Physiotherapy versus manipulation under anesthesia versus arthroscopic capsular release for patients referred to secondary care with a primary frozen shoulder: Study protocol for a randomised controlled trial. Trials 2017;18:614. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kim DH, Song KS, Min BW, Bae KC, Lim YJ, Cho CH. Early clinical outcomes of manipulation under anesthesia for refractory adhesive capsulitis: Comparison with arthroscopic capsular release. Clin Orthop Surg 2020;12:217-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Zuckerman JD, Rokito A. Adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2011;19:536-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Pandey V, Madi S. Clinical guidelines in the management of frozen shoulder: An update. Indian J Orthop 2021;55:299-309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Lee SJ, Jang JH, Hyun YS. Can manipulation under anesthesia alone provide clinical outcomes similar to arthroscopic circumferential capsular release in primary frozen shoulder? Clin Shoulder Elbow 2020;23:169-77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Grant JA, Schroeder N, Miller BS, Carpenter JE. Comparison of manipulation and arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2013;22:1135-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Kivimäki J, Pohjolainen T, Malmivaara A, Kannisto M, Guillaume J, Seitsalo S, et al. Manipulation under anaesthesia with home exercises versus home exercises alone in the treatment of frozen shoulder: A randomized controlled trial. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007;16:722-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Le Lievre HM, Murrell GAC Long-term outcomes after arthroscopic capsular release for idiopathic adhesive capsulitis. Arthroscopy 2012;28:916-24. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Cvetanovich GL, Leroux T, Verma NN, Bach BR Jr., Romeo AA, Nicholson GP. Clinical outcomes of arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2018;34:1304-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Rangan A, Goodchild L, Gibson J, Brownson P, Thomas M, Rees J, Kulkarni R. BESS/BOA Patient Care Pathways: Frozen Shoulder. Shoulder & Elbow. 2015;7(4):299-307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Hand GC, Athanasou NA, Matthews T, Carr AJ. The pathology of frozen shoulder. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2007;89:928-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Atoun E, Van Tongel A, Hous N, Narvani A, Sforza G, Levy O. Ultrasound findings after manipulation under anaesthesia for frozen shoulder. Acta Orthop Belg 2012;78:327-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Sasanuma H, Sugimoto H, Kanaya Y, Iijima Y, Saito T, Saito T, Watanabe H. Magnetic resonance imaging and short-term clinical results of severe frozen shoulder treated with manipulation under ultrasound-guided cervical nerve root block. J Shoulder & Elbow Surg. 2016;25:e13-e20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Uluyardimci E, Ocguder DA. Comparison of short-term clinical outcomes of manipulation under anesthesia and arthroscopic capsular release in treating frozen shoulder. Med J Islamic World Acad Sci 2020;28:55-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Cvetanovich GL, Verma NN, Nicholson GP. Arthroscopic capsular release for adhesive capsulitis. Arthrosc Tech 2016;5:e547-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]