Adding Pilates to conventional kinesiotherapy appears to be a safe and well-tolerated approach for chronic non-specific low back pain, offering promising gains in pain relief, functional ability, and flexibility.

Dr. Shruti Mahajan, Department of Physiotherapy, National Institute of Medical Science and Research, NIMS University, Jaipur-Delhi Highway (NH-11C), Jaipur, Rajasthan, India. E-mail: dr.mahajanshruti@gmail.com

Introduction: Chronic non-specific low back pain (CNSLBP) continues to pose a significant global health burden, often leading to persistent pain and functional limitations. Although conventional kinesiotherapy is a well-established approach in managing CNSLBP, the integration of Pilates a method emphasizing core stability, controlled movements, and neuromuscular re-education may offer additional therapeutic benefits. This pilot study aimed to assess the feasibility, safety, and preliminary clinical effects of combining Pilates-based exercises with conventional kinesiotherapy for individuals with CNSLBP.

Materials and Methods: A single-group pre-post intervention design was employed. Thirty adults diagnosed with CNSLBP participated in an 8-week program integrating Pilates and kinesiotherapy. Feasibility metrics included recruitment rate, retention, session adherence, acceptability (participant feedback), and safety (adverse events). Clinical outcomes assessed pre- and post-intervention included pain intensity (visual analog scale), functional disability (Roland-Morris Disability Questionnaire), lumbar mobility (Modified-modified Schober’s Test), and lumbo-pelvic flexibility (V-Sit and reach test).

Results: The study achieved a high recruitment rate (85.71%) and strong retention (86.67%). Mean adherence across 24 sessions was 75.64% (standard deviation = 21.72), with no adverse events reported. Participant feedback indicated moderate-to-high acceptability (mean score: 3.77 ± 0.85). Statistically significant improvements (P < 0.0001) were observed in all clinical outcome measures, including reductions in pain and disability and enhancements in lumbar mobility and flexibility.

Conclusion: The integration of Pilates with conventional kinesiotherapy is both feasible and safe for individuals with CNSLBP, demonstrating promising preliminary improvements in pain, function, and mobility. These findings support the need for larger-scale randomized controlled trials to further investigate the efficacy and long-term outcomes of this combined intervention approach.

Keywords: Chronic low back pain, non-specific low back pain, Pilates, conventional kinesiotherapy.

Chronic non-specific low back pain (CNLBP) is a prevalent cause of long-term disability, with nearly 80% of individuals experiencing low back pain (LBP) during their lifetime [1,2]. While many recover, a significant proportion develops chronic symptoms without identifiable pathology, hence termed “non-specific” [3]. The Global Burden of Disease (2019) ranked LBP as the leading cause of years lived with disability, especially in adults aged 40–69 years [4,5], with CNLBP largely influenced by sedentary behavior, poor ergonomics, psychosocial factors, and limited physical activity [6,7,8]. In India, prevalence varies across populations [9], and 10–20% of acute cases progress to chronic stages [10], leading to persistent pain, reduced work productivity, and increased healthcare costs [11,12]. CNLBP is a complex condition involving deficits in trunk control, core stability, spinal flexibility, and mobility [13,14,15]. Although kinesiotherapy has long been the standard rehabilitation method [16,17], growing evidence supports Pilates for its emphasis on controlled movement, alignment, and neuromuscular retraining [18,19], Conventional therapy, while beneficial, may not sufficiently target deep core activation, postural re-education, or neuromuscular control, often leading to limited long-term outcomes and reduced adherence [16,20,21,22,23]. Integrating Pilates with kinesiotherapy offers a more comprehensive approach, addressing motor control, spinal stability, and body awareness [18,24,25,26]. Studies show that Pilates enhances lumbar stability, trunk endurance, flexibility, and pain modulation, while its structured and progressive design improves patient engagement, making it a valuable addition to conventional rehabilitation [27,28]. Therefore, adding Pilates to conventional therapy has the potential to optimize clinical outcomes by addressing both the mechanical and neuromuscular contributors to CNLBP. Although kinesiotherapy and Pilates independently aid in managing CNLBP, their combined impact within rehabilitation programs remains underexplored. Most studies investigate them separately with varied methods, making it difficult to form integrated guidelines. Limited research has also assessed feasibility factors like adherence, safety, and retention. Pilot studies are therefore essential to evaluate the practicality and early benefits of combining Pilates with conventional physiotherapy for CNLBP. The aim of this pilot study is to evaluate the feasibility, safety, and acceptability of integrating Pilates into conventional kinesiotherapy for individuals with CNLBP. Specifically, it seeks to assess recruitment, adherence, and retention rates, while also exploring preliminary clinical outcomes such as pain intensity, functional disability, lumbar mobility, and lumbo-pelvic flexibility. The findings will help refine the intervention model and provide essential data for planning future large-scale trials.

Ethical approval

The study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of NIMS University, Jaipur, Rajasthan, India (Approval No: NIMS/PTOT/Ethical/Feb/2025/01). Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before their enrollment in the study.

Study design, setting, and duration

This was a prospective single-group pre-post pilot study conducted to assess the feasibility, safety, and preliminary clinical effects of integrating Pilates exercises into conventional kinesiotherapy for individuals with CNLBP. The study was carried out in the Department of Physiotherapy at Bundelkhand Medical College, Sagar (Madhya Pradesh) over a duration of 6 months.

Participants

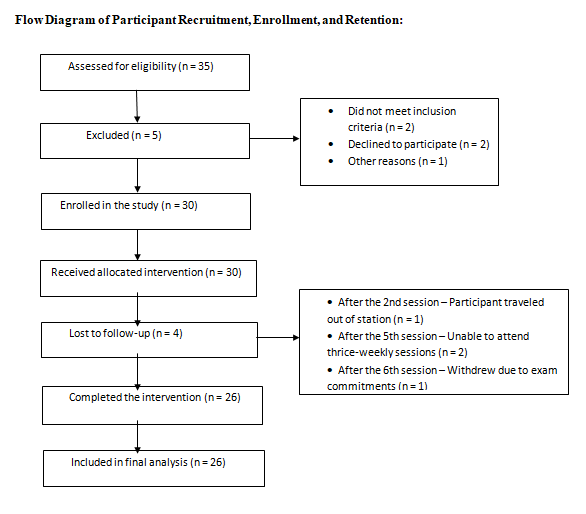

A total of 35 individuals were screened for eligibility. Of these, 30 met the inclusion criteria and were enrolled in the study. Eligible participants were adults aged 20–60 years with CNLBP persisting for ≥12 weeks, able to travel independently, and willing to provide informed consent. Exclusion criteria included acute or subacute LBP, neurological involvement, impaired mobility, prior physiotherapy within the past 6 months, pregnancy, major surgery, malignancy, or significant systemic illness. During the intervention, four participants discontinued and were excluded from the final analysis, leaving 26 participants who completed the 8-week program. The flow of participants through the recruitment, enrollment, and retention stages is summarized in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Flow diagram of participant recruitment, enrollment, allocation, and retention.

Intervention protocol

The intervention was conducted over 8 weeks, comprising 24 supervised sessions (3/week, ~60 min each). Each session included a 5–10-min warm-up, a main exercise module, and a 5–7-min cool-down. Abdominal bracing (drawing-in maneuver) was taught to all participants. The program alternated weekly between conventional kinesiotherapeutic exercises and mat-based Pilates to promote varied neuromuscular engagement.

The kinesiotherapy module included pelvic rocking, curl-ups, bridging, trunk extensions, bird-dog, dead bug, planks, cat-cow, and targeted stretches for hamstrings, piriformis, hip flexors, and thoracolumbar fascia. The Pilates module comprised single-leg circle, pelvic curl, hundreds, roll-up, table-top, swimming, swan, child’s pose, side kick, saw, shoulder bridge, and teaser.

Progression was structured as follows: Weeks 1–2 (2 sets × 15 reps), weeks 3–4 (2 sets × 20 reps), weeks 5–6 (3 sets × 15 reps), and weeks 7–8 (3 sets × 20 reps). Stretching was held for 10 s with equal rest, while strengthening involved body weight resistance with a 5-s hold and 2-second relaxation per repetition. All sessions were supervised by a qualified physiotherapist to ensure safety, correct technique, and adherence.

Outcome measures

Feasibility outcomes were assessed through recruitment rate (eligible vs. enrolled), retention rate (completed vs. enrolled), session adherence (attendance records), acceptability (participant feedback and interviews), and safety, determined by monitoring adverse events. Clinical outcomes included pain intensity, evaluated with the Visual Analog Scale (VAS); functional disability, assessed using the Roland-Morris disability questionnaire (RMDQ); lumbar mobility, measured by the Modified-modified Schober’s Test; and lumbo-pelvic flexibility, assessed with the V-sit and Reach Test. All measures were collected at baseline and again after completion of the 8-week intervention.

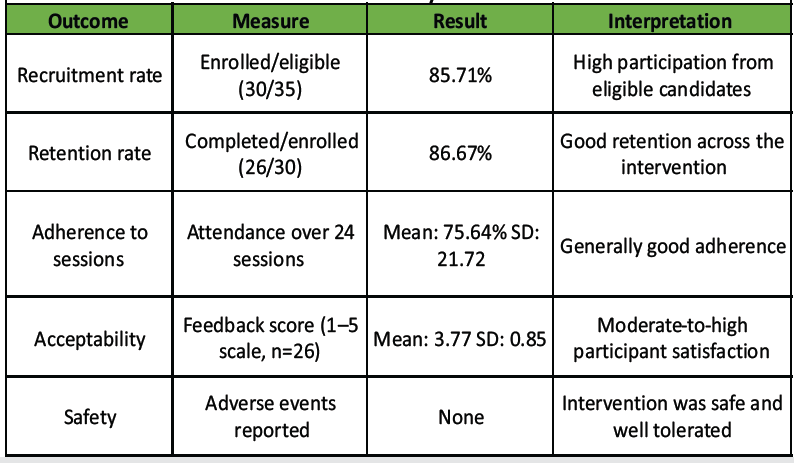

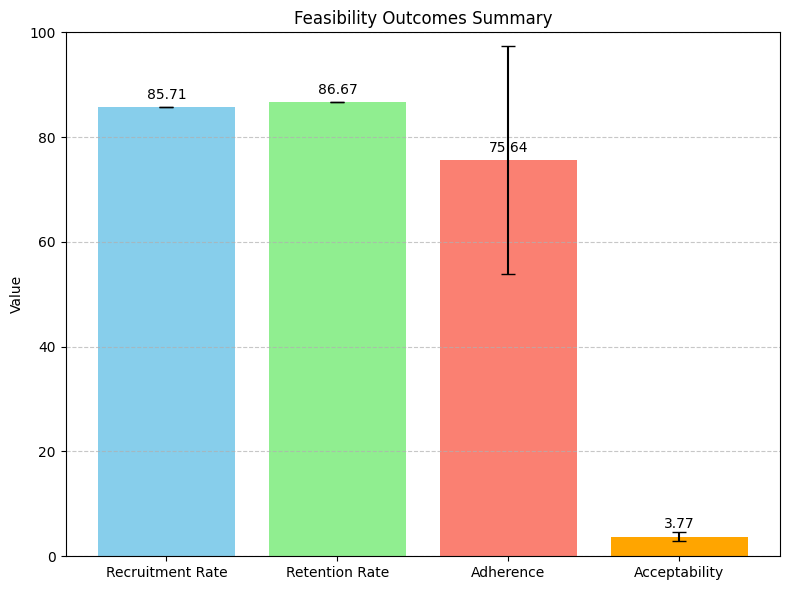

The intervention demonstrated high feasibility and safety, with recruitment of 85.71%, retention of 86.67%, mean session adherence of 75.64% (SD = 21.72), moderate-to-high acceptability (mean feedback score = 3.77 ± 0.85), and no adverse events (Table 1 and Fig. 2).

Table 1: Feasibility outcome

Figure 2: Feasibility outcomes of the integrated Pilates–kinesiotherapy intervention. The study achieved high recruitment (85.71%) and retention (86.67%) rates, with good adherence (75.64%) and moderate-to-high acceptability (mean feedback score: 3.77). No adverse events were reported, indicating the intervention was safe and well-tolerated.

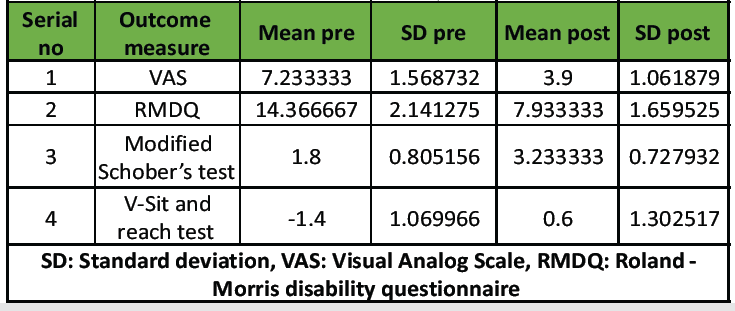

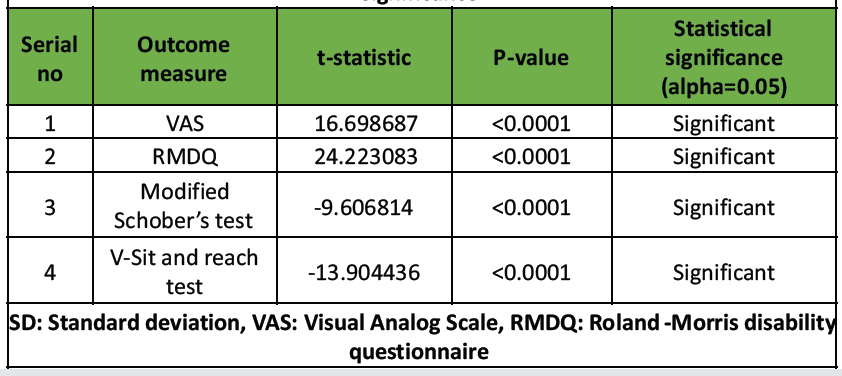

Clinically and functionally, participants showed significant improvements after the 8-week program: Pain intensity (VAS) and disability (RMDQ) decreased, with mean scores reducing from 7.23 to 3.90 and 14.37 to 7.93, respectively, while lumbar mobility (Modified Schober’s test) and flexibility (V-Sit and reach) increased from 1.80 to 3.23 and –1.40 to 0.60, respectively. All changes were statistically significant (t = 16.70–24.22; P < 0.0001) (Tables 2 and 3).

Table 2: Summary of clinical outcome measures: Pre- and post-intervention analysis

Table 3: Pre-post intervention differences in outcome measures: t-statistics and significance

The intervention protocol demonstrated strong feasibility, evidenced by high recruitment (85.7%) and retention (86.7%), indicating the target population was engaged and well-matched. Session adherence averaged 75.6%, reflecting good commitment despite the program’s intensity. Participants reported moderate-to-high acceptability (3.77/5), and no adverse events were observed, highlighting safety and tolerability. Overall, the findings indicate that the protocol was manageable, acceptable, and suitable for future clinical or research implementation. Despite the intervention’s overall feasibility, several challenges were noted. Session adherence averaged 75.6% but varied widely, with some participants attending less than half of sessions due to personal, transportation, or health-related issues, potentially affecting intervention consistency. Recruitment was ultimately successful (85.7%) but initially hindered by eligibility screening and participant time constraints. Sustaining engagement required ongoing communication, and early withdrawals (4 of 30) highlighted the need for strategies to boost motivation and reduce attrition, which is crucial for scaling future interventions. Preliminary results from this pilot study indicate that integrating Pilates with kinesiotherapy may positively impact chronic LBP (CLBP). All outcomes – pain, functional disability, lumbar mobility, and flexibility – showed significant improvements. Pain (VAS) decreased from 7.23 to 3.90 and functional disability (RMDQ) from 14.37 to 7.93, suggesting enhanced core stability and daily functioning. Physical performance also improved, with lumbar mobility (Modified Schober’s Test) rising from 1.80 cm to 3.23 cm and flexibility (V-sit and reach) from -1.40 cm to +0.60 cm. These findings highlight potential benefits of the combined intervention, though they are preliminary due to the small sample and pilot design. The findings of this pilot study are consistent with previous research supporting the use of Pilates and kinesiotherapy in the management of CLBP. Mostagi et al. found Pilates to be more effective than general exercise in reducing pain and disability, which aligns with the significant improvements observed in both VAS and RMDQ scores in the present study [29]. Similarly, Llewellyn et al. reported substantial reductions in perceived pain and functional disability following a structured Pilates program, emphasizing the role of movement control and body awareness principles that likely contributed to the observed benefits [30]. Popli further highlighted the clinical value of integrating Pilates within broader rehabilitation protocols, suggesting that combining it with conventional kinesiotherapy may enhance functional outcomes, as seen in this trial [31]. Supporting this integrated approach, Faria et al. demonstrated improved pain and mobility outcomes through the combined use of Pilates and kinesiotherapy in pregnant women with LBP, reinforcing its applicability across diverse populations [32]. Collectively, these studies bolster the preliminary evidence from the present investigation, suggesting that Pilates combined with kinesiotherapy may produce synergistic benefits for individuals with CNLBP. The 8-week intervention duration employed in this study aligns with previous research on Pilates for CLBP, where programs of similar length have demonstrated significant improvements in pain, functional disability, and lumbo-pelvic stability [28,29]. While these results are consistent with prior research supporting the effectiveness of Pilates and kinesiotherapy in managing CLBP, certain methodological limitations of the current study should be noted. This pilot study assessed only physical outcomes pain, functional disability, lumbar mobility, and lumbo-pelvic flexibility alongside feasibility parameters, including recruitment, retention, adherence, acceptability, and safety. These measures were selected to provide objective indicators of short-term therapeutic responsiveness and to evaluate the practicality and tolerability of the intervention protocol. Psychosocial outcomes, such as fear-avoidance beliefs, anxiety, and quality of life, were beyond the scope of this initial study but will be incorporated in future randomized controlled trials to comprehensively assess the multidimensional impact of the combined intervention. As a pilot investigation, the modest sample size was intentionally chosen to assess feasibility, safety, and preliminary therapeutic outcomes before progressing to a larger randomized controlled trial. The absence of a control group reflects the exploratory nature of the study, emphasizing procedural refinement, participant adherence, and intervention acceptability rather than establishing definitive causal relationships. Despite these constraints, the findings provide a valuable foundation for future controlled investigations designed to validate the clinical efficacy of this integrative approach. Furthermore, this pilot study was conducted at a single institution with purposive recruitment to evaluate the feasibility, safety, and preliminary effects of the intervention. While this design limits generalizability to broader populations and varied clinical settings, it provides essential data to refine the intervention protocol and inform future multicenter randomized controlled trials.

Limitations

This pilot study has several limitations. The small sample size, single-center design, and absence of a control group limit the generalizability and causal interpretation of the findings. The short intervention period and lack of long-term follow-up restrict evaluation of sustained effects. Moreover, only physical outcomes – pain, disability, mobility, and flexibility – were assessed, while psychosocial factors such as fear-avoidance beliefs, anxiety, and quality of life were not included. Despite these constraints, the study provides valuable preliminary data to refine the intervention and guide future multicenter randomized controlled trials.

Future research directions

This pilot study demonstrates preliminary benefits of integrating Pilates with conventional kinesiotherapy for CLBP, including improvements in pain, functional disability, lumbar mobility, and flexibility. Future multicenter randomized controlled trials with larger, diverse samples, appropriate control groups, extended interventions, and long-term follow-up are needed to confirm effectiveness and sustainability. Inclusion of psychosocial outcomes such as fear-avoidance beliefs, anxiety, and quality of life will enable a more comprehensive assessment of the intervention’s multidimensional impact.

This pilot study demonstrates that an integrated Pilates and kinesiotherapy program is a feasible intervention for individuals with CNLBP, evidenced by favorable recruitment, retention, adherence, acceptability, and safety outcomes. Preliminary results indicate significant improvements in pain, functional disability, mobility, and flexibility, suggesting the potential effectiveness of this combined approach. These encouraging findings support the need for larger, well-designed randomized controlled trials to further evaluate the efficacy and long-term benefits of Pilates-integrated interventions in managing CNLBP.

This pilot study suggests that combining Pilates with conventional kinesiotherapy may enhance clinical outcomes in chronic non-specific low back pain and can be safely incorporated into physiotherapy programs.

References

- 1. Hoy D, Bain C, Williams G, March L, Brooks P, Blyth F, et al. A systematic review of the global prevalence of low back pain. Arthritis Rheum 2012;64:2028-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Hoy D, Brooks P, Blyth F, Buchbinder R. The epidemiology of low back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:769-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Krismer M, Van Tulder M. Low back pain (non-specific). Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2007;21:77-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Murray CJ. The global burden of disease study at 30 years. Nat Med 2022;28:2019-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Wu A, March L, Zheng X, Huang J, Wang X, Zhao J, et al. Global low back pain prevalence and years lived with disability from 1990 to 2017: Estimates from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2017. Ann Transl Med 2020;8:299. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Maher C, Underwood M, Buchbinder R. Non-specific low back pain. Lancet 2017;389:736-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Bener A, Verjee M, Dafeeah EE, Falah O, Al-Juhaishi T, Schlogl J, et al. Psychological factors: Anxiety, depression, and somatization symptoms in low back pain patients. J Pain Res 2013;6:95-101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Shetty GM, Shah N, Arenja A. Occupation-based demographic, clinical, and psychological presentation of spine pain: A retrospective analysis of 71,727 patients from urban India. Work 2024;78:181-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Shetty GM, Jain S, Thakur H, Khanna K. Prevalence of low back pain in India: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Work 2022;73:429-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Hüllemann P, Keller T, Kabelitz M, Gierthmühlen J, Freynhagen R, Tölle T, et al. Clinical manifestation of acute, subacute, and chronic low back pain in different age groups: Low back pain in 35,446 patients. Pain Pract 2018;18:1011-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Chang D, Lui A, Matsoyan A, Safaee M, Aryan H, Ames C. Comparative review of the socioeconomic burden of lower back pain in the United States and globally. Neurospine 2024;21:487-501. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Fatoye F, Gebrye T, Ryan CG, Useh U, Mbada C. Global and regional estimates of clinical and economic burden of low back pain in high-income countries: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Front Public Health 2023;11:1098100. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Li W, Gong Y, Liu J, Guo Y, Tang H, Qin S, et al. Peripheral and central pathological mechanisms of chronic low back pain: A narrative review. J Pain Res 2021;14:1483-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Norris CM. Back Stability: Integrating Science and Therapy. Compaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2008. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Makris UE, Paul TM, Holt NE, Latham NK, Ni P, Jette A, et al. The relationship among neuromuscular impairments, chronic back pain, and mobility in older adults. PM R 2016;8:738-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Lizier DT, Perez MV, Sakata RK. Exercises for treatment of nonspecific low back pain. Rev Braz Anesthesiol 2012;62:838-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Van Middelkoop M, Rubinstein SM, Verhagen AP, Ostelo RW, Koes BW, Van Tulder MW. Exercise therapy for chronic nonspecific low-back pain. Best Pract Res Clin Rheumatol 2010;24:193-204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Wood S. Pilates for Rehabilitation. Compaign, IL: Human Kinetics; 2019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Di Lorenzo CE. Pilates: What is it? Should it be used in rehabilitation? Sports Health 2011;3:352-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Hayden JA, Van Tulder MW, Malmivaara A, Koes BW. Exercise therapy for treatment of non‐specific low back pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2005;2005:CD000335. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. O’Sullivan P. Diagnosis and classification of chronic low back pain disorders: Maladaptive movement and motor control impairments as underlying mechanism. Man Ther 2005;10:242-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Sluijs EM, Knibbe JJ. Patient compliance with exercise: Different theoretical approaches to short-term and long-term compliance. Patient Educ Couns 1991;17:191-204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Sabaté E, editor. Adherence to Long-Term Therapies: Evidence for Action. Geneva: World Health organization; 2003. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Lee K. The relationship of trunk muscle activation and core stability: A biomechanical analysis of pilates-based stabilization exercise. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2021;18:12804. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. De Oliveira NT, Freitas SM, Fuhro FF, Da Luz MA Jr., Amorim CF, Cabral CM. Muscle activation during Pilates exercises in participants with chronic nonspecific low back pain: A cross-sectional case-control study. Arch Phys Med Rehabil 2017;98:88-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. De Oliveira LC, De Oliveira RG, De Almeida Pires-Oliveira DA. Effects of Pilates on muscle strength, postural balance and quality of life of older adults: A randomized, controlled, clinical trial. J Phys Ther Sci 2015;27:871-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Lim EC, Poh RL, Low AY, Wong WP. Effects of Pilates-based exercises on pain and disability in individuals with persistent nonspecific low back pain: A systematic review with meta-analysis. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2011;41:70-80. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Phrompaet S, Paungmali A, Pirunsan U, Sitilertpisan P. Effects of pilates training on lumbo-pelvic stability and flexibility. Asian J Sports Med 2011;2:16-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Mostagi FQ, Dias JM, Pereira LM, Obara K, Mazuquin BF, Silva MF, et al. Pilates versus general exercise effectiveness on pain and functionality in non-specific chronic low back pain subjects. J Bodyw Mov Ther 2015;19:636-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Llewellyn H, Konstantaki M, Johnson MI, Francis P. The effect of a Pilates exercise programme on perceived functional disability and pain associated with non-specific chronic low back pain. MOJ Yoga Phys Ther 2017;2:25-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Shreya, Popli A. Enhancing rehabilitation through Pilates: A comprehensive approach. J Clin Diagn Res 2024;18:56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 32. Faria GS, Dos Santos AE, De Moura Costa D, Carregosa FJ, De Carvalho FL, Rezende AA. Application of the Pilates method and kinesiotherapeutic approach in pregnant women with low back pain: An integrative review. J Res Knowl Spreading 2022;3:e14013. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]