Arthroscopic single-row repair offers a cost-effective and clinically effective solution for managing small-to-medium rotator cuff tears in resource-constrained settings such as India, delivering excellent functional outcomes without compromising surgical quality or patient satisfaction. The Penn Shoulder Score provided a nuanced assessment, confirming not just objective improvement but also the patients’ own satisfaction with the result.

Dr. Asad Khan, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, B.R.D Medical College and Nehru Hospital, Gorakhpur, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: khanasad53@gmail.com

Introduction: Rotator cuff tears are a common cause of shoulder pain and disability. Arthroscopic repair is the preferred surgical approach for symptomatic full-thickness tears that fail conservative management. Single-row and double-row techniques are widely used, but clinical outcomes for small-to-medium tears are often comparable. This study aimed to evaluate functional outcomes following arthroscopic single-row rotator cuff repair using the Penn shoulder score (PSS).

Materials and Methods: Thirty patients (aged 18–60 years) with small-to-medium full-thickness rotator cuff tears, unresponsive to at least 6 months of non-operative management, underwent arthroscopic single-row repair with bioabsorbable suture anchors. Patients were evaluated using the PSS preoperatively and at follow-up visits at 2, 6, 10, 24 weeks, and final review (~12 months). The PSS evaluates pain, function, and patient satisfaction on a 100-point scale. Data were analyzed using paired t-tests (P < 0.05).

Results: The cohort had a mean age of 38.9 years; 70% were male. All tears were either small or medium per Cofield’s classification. The mean PSS improved from 30.4 ± 3.9 preoperatively to 98.4 ± 3.8 at final follow-up (P < 0.001), with significant gains at each interval. At 1 year, 93.3% achieved an “Excellent” outcome, and all patients were satisfied with their results. No re-tears or major complications were reported.

Conclusion: Arthroscopic single-row rotator cuff repair provides excellent functional outcomes and high patient satisfaction for small-to-medium tears. The technique is cost-effective and safe, making it especially suitable for resource-constrained settings like India.

Keywords: Rotator cuff tear, arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, single-row repair, Penn shoulder score, shoulder outcome.

Shoulder pain is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal complaints, with a lifetime prevalence reported as high as 67% in the general population [1]. Rotator cuff pathology is a leading cause of chronic shoulder pain and dysfunction, especially in middle-aged and older adults. Epidemiological studies have noted that shoulder pain prevalence increases with age and is common in working populations [1,2]. In India, the burden of shoulder pain and rotator cuff tears is significant but not well quantified [2]. Patients with rotator cuff tears often experience pain, weakness (particularly with arm elevation and external rotation) [3], and difficulty with overhead activities [4]. Conservative treatments (rest, physical therapy, anti-inflammatories, injections) are first-line for rotator cuff tendinopathy and partial tears. However, a substantial subset of patients (approximately 40%) fail to improve with non-operative management and have persistent or recurrent symptoms [5]. In full-thickness rotator cuff tears, surgical repair is frequently indicated to relieve pain and restore function, particularly if symptoms are severe or chronic. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair has become the gold-standard surgical approach for reparable tears, largely replacing traditional open or mini-open techniques. Arthroscopy offers the advantages of smaller incisions, less deltoid disruption, and faster rehabilitation, while achieving comparable clinical outcomes to open repair [6]. There is an ongoing debate regarding the optimal suture configuration for arthroscopic rotator cuff repair. The two commonly used techniques are the single-row repair (anchors placed in a single medial row securing the tendon edge) and the double-row or suture-bridge repair (medial and lateral rows of anchors creating a broader footprint compression) [6]. Biomechanically, double-row constructs can provide greater footprint contact area and higher initial fixation strength as reported by Lorbach et al. [7]. Some studies have shown lower re-tear rates with double-row repairs for larger tears [8]. However, multiple clinical trials and meta-analyses have found no significant difference in functional outcomes between single-row and double-row repairs for small-to-medium tears [9,10,11]. For example, Chen et al. reported that clinical scores and range of motion did not differ meaningfully between the two techniques at mid-term follow-up [9]. Millet et al. [10] have discussed that double row repair may be superior in large tears, but when all size tears are included, there is no difference between the two techniques. Single-row repair thus remains widely used, as it is technically less complex, requires fewer anchors (cost-effective), and yields outcomes equivalent to double-row in many cases [12,13]. Given the prevalence of rotator cuff tears and the need to optimize surgical outcomes, it is important to evaluate the results of repair techniques in various settings. While numerous studies abroad have documented good-to-excellent outcomes after arthroscopic cuff repair [14,15], there is relatively limited prospective data from the Indian subcontinent on single-row repairs. The Penn shoulder score (PSS) is a validated, comprehensive instrument to assess shoulder function, combining pain (30 points), satisfaction (10 points), and function (60 points) sub-scores into a 100-point scale (100 indicating no pain, full function, and high satisfaction) [16]. The present study was designed as a prospective evaluation of patients undergoing arthroscopic single-row rotator cuff repair, using the PSS to quantify functional outcomes over time. We hypothesized that single-row arthroscopic repair would result in significant improvements in shoulder function and high patient satisfaction, with outcomes comparable to those reported in the literature for similar tear sizes.

Study design and setting

A prospective cohort study was conducted in the department of orthopedic surgery at a tertiary care institute. The institutional ethical committee approval (IEC No. 233/IHEC/2025) was obtained before study initiation. Thirty-five patients with rotator cuff tears were initially enrolled to account for potential dropouts, and 30 patients (with complete follow-up data) were included in the final analysis. Based on 80% power, 5% significance, and an expected effect size derived from prior studies on functional score improvements, the minimum sample size required was 27 patients. To account for potential dropouts, 35 patients were enrolled, and 30 with complete follow-up were included in the analysis. All patients provided written informed consent to participate in the study.

Patient selection

Adults aged 18–60 years presenting with chronic shoulder pain and dysfunction due to a full-thickness rotator cuff tear were screened. Inclusion criteria were: (1) imaging-confirmed small or medium-sized rotator cuff tear (supraspinatus or supraspinatus-plus-partial infraspinatus tear, as per Cofield’s classification), (2) duration of symptoms ≥6 months, (3) failure to improve with ≥6 months of conservative management (physiotherapy, analgesics, and/or subacromial injections), and (4) willingness to undergo arthroscopic repair with written consent. Patients were excluded if they had massive or irreparable tears (Patte’s grade 3 retraction, large tear (as per Cofield criteria) or Grade >3 fatty infiltration of cuff muscles as per Goutallier classification, significant muscle atrophy, prior surgery on the affected shoulder, concomitant shoulder instability or arthritis, or medical contraindications to surgery.

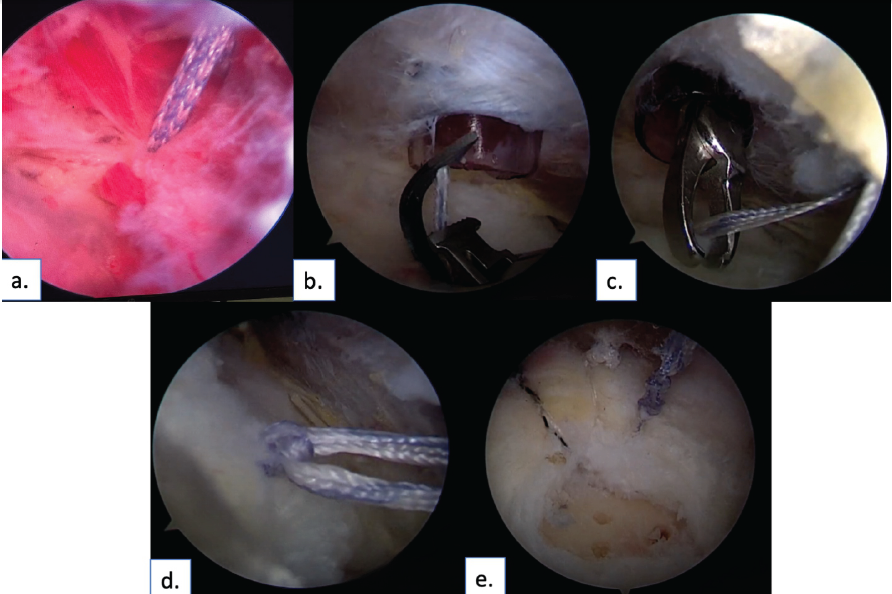

Surgical technique

All surgeries were performed by experienced surgeons under general anesthesia (with interscalene block) in the lateral decubitus position. A diagnostic arthroscopy was performed, and any intra-articular pathology was addressed. After subacromial decompression, the rotator cuff was repaired using one or more bioabsorbable suture anchors placed in a single-row configuration at the greater tuberosity. Sutures were passed through the tendon and tied arthroscopically in simple or mattress fashion. The number of anchors (typically 1–2) depended on tear size. Arthroscopic images of one of the patients have been added for illustration purposes in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: Showing surgical technique/arthroscopic images of single row rotator cuff repair step-wise in one of our patients. (a) Anchor placed on rotator cuff footprint, (b) Use of Scorpion to pass suture bite through the cuff, (c) Retrieving of suture, (d) tying of knot via knot pusher (e). Final arthroscopic repair image.

Rehabilitation

Postoperatively, patients were immobilized in a sling for 4–6 weeks, allowing only pendulum exercises initially. Passive and assisted range-of-motion exercises began after 1 week. Active motion commenced from 6 to 8 weeks, and strengthening exercises were introduced at 10–12 weeks. All patients followed a structured, supervised physiotherapy program.

Outcome measures

The primary outcome was the PSS, measured preoperatively and at 2, 6, 10, 24 weeks, and final follow-up (~12 months). The PSS is a validated 100-point scale assessing pain (30 points), function (60 points), and patient satisfaction (10 points). Secondary outcomes included overall patient satisfaction and a categorical grading (excellent, good, fair, poor) based on the final PSS and clinical assessment. While additional tools such as Constant–Murley or UCLA scores can provide complementary data, we opted for a single validated score to ensure consistency and reduce inter-scale variability.

Data analysis

Continuous data (e.g., PSS scores) were summarised as mean ± standard deviation. Categorical data were expressed as frequencies and percentages. Paired t-tests were used to evaluate changes over time. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analysis was conducted using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences.

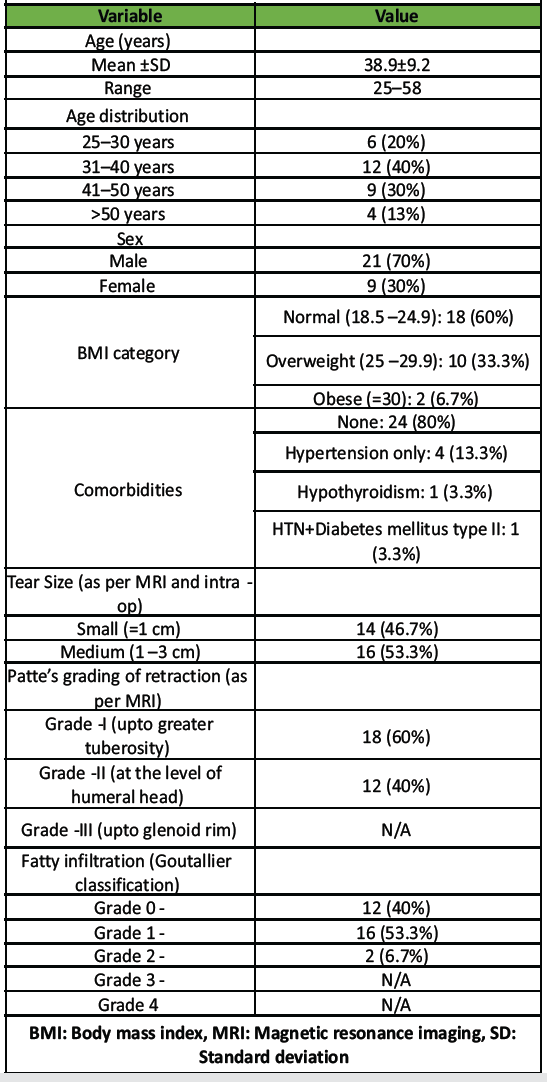

Patient demographics and characteristics

The mean age of the cohort (n = 30) was 38.9 ± 9.2 years (range: 25–58), with the majority (70%) being male. The most common age group was 31–40 years (40%). Right shoulder involvement (dominant side) was seen in 60% of patients. The average body mass index was 24.1 kg/m², and 80% had no comorbidities. Hypertension was present in 13.3%, while only one patient each had hypothyroidism or diabetes. All patients had imaging-confirmed small (46.7%) or medium (53.3%) full-thickness supraspinatus tears. Detailed demographics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1: Patient demographics and clinical characteristics (n=30)

Perioperative outcomes

All surgeries were completed successfully using the single-row technique with 1–2 bioabsorbable suture anchors. The mean operative time was 60 min. One patient (3.3%) developed a superficial portal-site infection, which resolved with oral antibiotics. No re-tears or significant complications were reported. No patient required revision or manipulation under anesthesia. All patients were satisfied with the surgical experience and outcome.

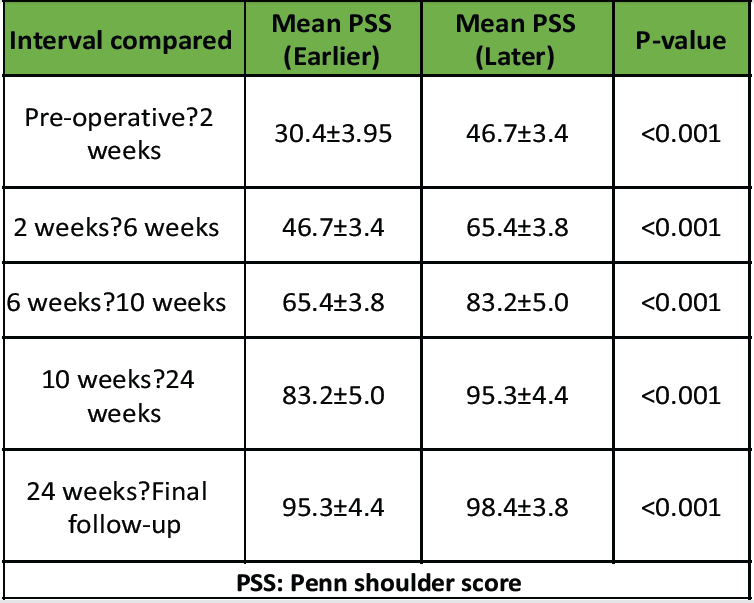

Functional outcomes – PSS

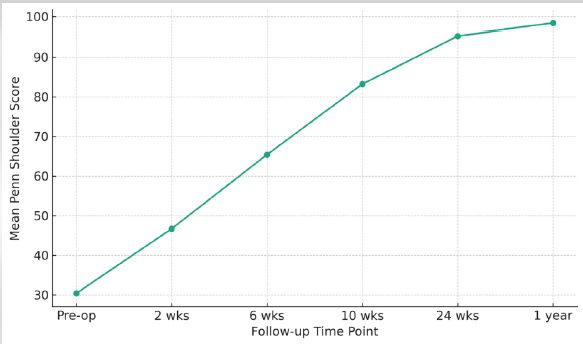

The PSS improved significantly across all time points. The pre-operative mean score was 30.4 ± 3.95, rising to 98.4 ± 3.8 at the final follow-up (~12 months, P < 0.001). Substantial gains were observed as early as 2 weeks (mean: 46.7), progressing to 65.4 (6 weeks), 83.2 (10 weeks), and 95.3 (24 weeks). Each interval demonstrated statistically significant improvement from the previous one (P < 0.001). Full PSS comparisons are shown in Table 2 and Fig. 2.This indicates that nearly all patients attained minimal pain, high satisfaction, and full or near-full shoulder function after their rotator cuff repair and rehab program.

Table 2: Comparison of Penn shoulder scores

Figure 2: Trajectory of PENN shoulder score improvement post-rotator cuff repair. Most functional gains occurred within the first 3–6 months.

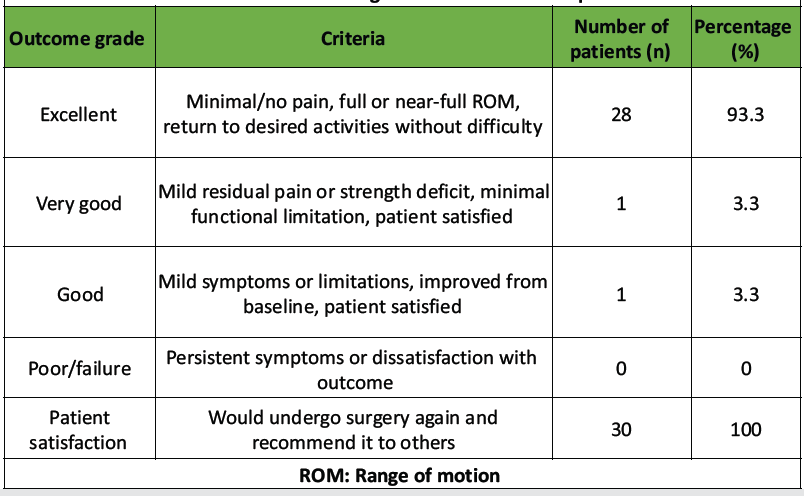

Outcome grades

At final follow-up, an outcome grading was assigned based on each patient’s overall shoulder function and comfort. Twenty-eight patients (93.3%) achieved an “Excellent” outcome, meaning they had little to no pain, a full range of motion (or only slight, non-limiting deficits), and had returned to their desired activities without difficulty. Of the remaining two patients, one (3.3%) had a “Very Good” outcome and one (3.3%) a “Good” outcome – these patients had mild residual pain or strength deficit but were still satisfied and much improved from baseline. Importantly, no patient had a poor outcome or failure. These results indicate a very high success rate for arthroscopic single-row repair in this cohort. In terms of patient-reported satisfaction, all 30 patients stated that they would undergo the surgery again and recommend it to others, given the improvement they experienced (Table 3).

Table 3: Outcome grades at final follow-up

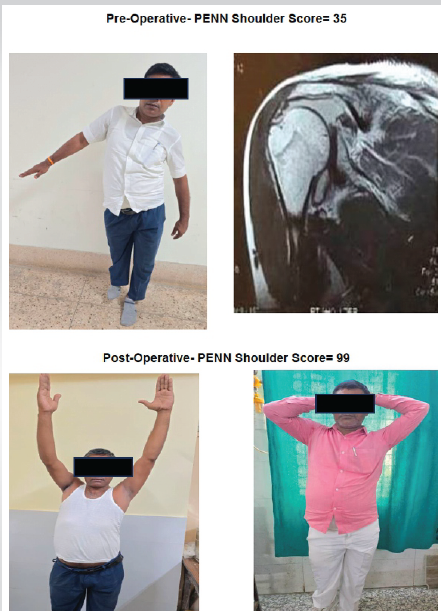

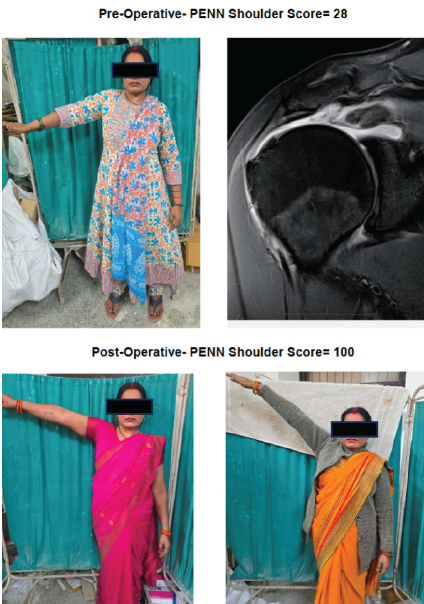

Outcomes of 2 cases have been illustrated in Figs. 3 and 4, respectively. These cases highlight that even patients with relatively low baseline shoulder scores can recover to excellent functional levels with proper surgical repair and therapy. Both patients had isolated supraspinatus tears and no significant comorbidities, which likely contributed to their favorable prognosis. Notably, their age (late 30s to early 40s) may have also been advantageous for healing. Across the cohort, similar robust improvements were observed irrespective of gender or minor comorbid status.

Figure 3: 42-year-old male patient presented with a right shoulder full-thickness supraspinatus tear after a fall injury, complaining of pain and inability to perform overhead activities for 8 months. Pre-operative PENN shoulder score (PSS) was 35, and magnetic resonance imaging showed a medium full-thickness supraspinatus tear. Single-row arthroscopic repair was done. Final follow-up showing excellent outcome with a PSS of 99.

Figure 4: 39-year-old female patient presented with a right shoulder full-thickness supraspinatus tear after a fall injury. She experienced progressive shoulder pain for a year, difficulty in dressing and lifting objects, and had failed physiotherapy. Her pre-operative PENN Shoulder score (PSS) was 28, and magnetic resonance imaging showed full full-thickness supraspinatus tear. Single-row arthroscopic repair was done. Final follow-up up- showing excellent outcome with a PSS of 100.

In this prospective study, arthroscopic single-row rotator cuff repair yielded outstanding functional outcomes in patients with small-to-medium full-thickness tears. The findings demonstrated a 93% rate of excellent results, as measured by a near-maximal PSS at 1-year follow-up. Our patient population (mean age ~39 years) was somewhat younger than that in many Western rotator cuff studies, which often have means in the 50s or 60s. This younger demographic could be due to different activity profiles and health-seeking behavior in our region, and it may partly explain the excellent healing observed (younger patients generally have better tendon healing capacity). Yadav et al. (2023), in a retrospective single-row cuff repair study from another center, reported a mean age of 51.8 years [12], and Vasu Bangera et al. (2019) had a mean age of ~51.7 years in their series [13]. Despite age differences, our outcomes were comparably positive, if not better. Notably, our cohort had a high proportion of male patients (70%). Some prior Indian series also showed male predominance [17], although rotator cuff tears in general do not have a strong gender bias. Hand dominance was a contributing factor: 60% had right shoulder tears, consistent with reports that the dominant arm is more prone to cuff injury [18]. Yamamoto et al. found dominant-arm tears were significantly more frequent, likely due to greater cumulative use and strain [19]. All our patients underwent single-row anchor repair with bioabsorbable anchors, and none had a prior cuff repair. Therefore, our results specifically reflect outcomes of primary single-row repairs in virgin tears. The complication rate was extremely low – only one superficial infection (3.3%) and no stiffness requiring intervention, underscoring the safety of the arthroscopic approach. Similarly, Yadav et al. (2023) reported only a 2.5% minor complication rate (one superficial skin infection and transient stiffness) in their series of 40 patients [12]. No patient in our study had a symptomatic re-tear within 1 year. While we did not perform routine post-op imaging, the clinical integrity was maintained in all cases. This could be attributed to the exclusion of massive tears and the relatively short follow-up (re-tears often present later). The literature indicates re-tear rates can range from 20% to 25% in rotator cuff repairs, especially in larger or older tears [20,21]. By focusing on small-to-medium tears, our study likely captured the subgroup with higher healing potential. It is also plausible that meticulous surgical technique and rigorous rehab contributed to secure healing. The PSS proved to be a sensitive measure of recovery, capturing improvements in pain, satisfaction, and function. The steep rise in PSS in the early post-operative weeks in our data reflects rapid pain relief after surgery – patients often reported that their night pain resolved and baseline discomfort dramatically lessened within the first 2–4 weeks of repair. Function scores improved more gradually, paralleling the phased rehabilitation; substantial gains in active motion and strength occurred after 6–12 weeks once immobilization was over. By 6 months, most patients had regained nearly full shoulder function, which was sustained at 1 year. These results align with other outcome measures reported in similar studies. Jadhav et al. (2019) conducted a prospective study of single-row arthroscopic cuff repairs using bioabsorbable anchors and noted significant improvements in constant scores from a pre-operative mean of ~32.7 to ~78.7 at 1 year [17]. Our patients’ PSS improving from ~30 to ~98 is analogous, considering PSS and constant score are different scales, but both measure pain and function. Kamat et al. (2019) reported an increase in the UCLA shoulder rating score from 8.75 pre-operative to 31.8 post-operative at 12 months (P < 0.001) [22], again reflecting excellent restoration of function, which is consistent with our PSS findings. Furthermore, Vamsinath et al. (2018) observed the UCLA score rising from ~9 pre-operative to 28.5 at 1 year in their arthroscopic repair series [23]. These improvements across different scoring systems corroborate that arthroscopic repair yields substantial functional benefits. In our series, 93% achieved excellent outcomes (using our criteria equating roughly to PSS ≥90). This success rate is higher than some reports, likely due to the smaller tear sizes and possibly the shorter-term follow-up. Jacob et al. (2020), in an Indian study of arthroscopic rotator cuff repairs, found 22% excellent, 43% good, 23% fair, and 12% poor results using the UCLA scale [24]. That study included a mix of tear sizes and a longer follow-up, which might explain the lower proportion of top outcomes. Notably, even in Jacob’s study, the majority (65%) had good-to-excellent results, and functional scores improved over time. Our outcome distribution (100% excellent/good) indicates that for small and medium tears, a single-row repair can reliably restore function with proper patient selection and technique. It is worth emphasizing that none of our patients had a “poor” outcome, which underscores the effectiveness of the intervention in this cohort. In the wider literature, most authors report good or excellent results in over 80% of patients after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair, especially for non-massive tears [21,25]. Our findings concur with these and even exceed some outcomes, possibly reflecting the advantages of a consistent surgical method and rigorous rehabilitation. One point of discussion is the single-row versus double-row debate. Our study did not directly compare the two techniques, but the excellent outcomes achieved with single-row repair lend further clinical support to its use. Biomechanically, double-row repairs have shown improved footprint contact and potentially stronger initial fixation [26]. However, clinical meta-analyses (e.g., Chen et al., 2013) have concluded that functional scores, muscle strength, and range of motion are statistically similar between single and double-row repairs in most comparative trials [9]. Additionally, some studies have found that double-row repairs do not eliminate the risk of re-tear; long-term follow-ups have shown re-tears can occur with either technique, especially if tendon quality is poor or if biological healing factors are unfavorable [27,28]. Our successful results with single-row repair (with 0% clinical re-tear in 1 year) suggest that for the small to moderate tear sizes, a well-executed single-row is sufficient to restore function. The advantages of single-row include fewer anchors (reducing cost), potentially less operative time, and simpler revision if needed. In the context of our resource-limited setting, these advantages are important. All our repairs were done with 1–2 anchors; had we used a double-row, that might have doubled the implant cost without a clear incremental benefit to the patient. Notably, Vasu Bangera et al. (2019) concluded single-row repair is a “cost-effective technique” that achieves good-to-excellent outcomes in the majority of cases, comparable to any published series of double-row repairs [13]. Our study reinforces that sentiment.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. The sample size was small (n = 30) and lacked a comparison group, which limits generalizability. The 12-month follow-up may not capture late re-tears or degenerative changes. Future multi-center studies with larger cohorts and long-term follow-up (2–5 years) are necessary for confirmation of durability. Tendon integrity was not confirmed with postoperative magnetic resonance imaging, so asymptomatic re-tears cannot be ruled out. The inclusion of only small-to-medium tears introduces a selection bias toward better prognosis, as larger or massive tears typically have inferior outcomes. As a single-centre study led by experienced surgeons, results may reflect ideal conditions. In addition, outcomes based on patient-reported scores like the PSS are subject to bias. Nonetheless, the prospective design, consistent surgical technique, and complete follow-up enhance the study’s reliability. This study aimed to assess the functional outcomes of a homogeneous single-row cohort, and future randomized controlled trials comparing single versus double row or conservative treatment are warranted.

Arthroscopic single-row rotator cuff repair is a highly effective treatment for small-to-medium full-thickness rotator cuff tears, resulting in excellent functional outcomes and patient satisfaction. In our prospective cohort, the PSS improved from a mean of ~30 pre-op to ~98 (indicating substantial impairment) at 1-year post-operative, with statistically significant improvements noted as early as 2 weeks and continuing through 6 months. By final follow-up, over 90% of patients achieved an excellent result, regaining near-normal shoulder function and experiencing minimal pain. Patients with minimal retraction (Patte I) and moderate retraction (Patte II) both achieved excellent PSS at 1 year (mean >95). Since severe retractions (Patte III) were excluded, our conclusions apply to small-to-medium tears with limited retraction and Grade 0–2 fatty infiltration. The procedure was associated with a low complication rate (3.3% minor infection, no other adverse events, re-operations) and no clinical failures in the short term to mid term. These results highlight that the single-row technique, coupled with proper patient selection and rehabilitation, can reliably restore shoulder function in the majority of rotator cuff tear patients. Given its advantages in simplicity and cost, the single-row repair should continue to be utilized as a primary surgical option, especially in resource-conscious settings. Long-term studies and comparative trials will further clarify if these excellent outcomes are maintained over time and how they stack up against newer repair modalities. Based on our findings, we conclude that arthroscopic single-row rotator cuff repair is a safe, cost-effective, and successful surgical strategy for treating full-thickness rotator cuff tears, yielding high rates of pain relief, functional recovery, and patient satisfaction.

This study highlights the effectiveness of arthroscopic single-row repair in working-age adults with small-to-medium rotator cuff tears. The Penn Shoulder Score effectively captured both functional improvement and patient satisfaction. With 100% of patients satisfied and minimal complications, the technique is validated as safe, reliable, and suitable for resource-limited settings. While double-row constructs may offer biomechanical advantages, our outcomes support the clinical sufficiency of single-row repair. Future studies with larger cohorts, longer follow-up, and comparative designs will further clarify its long-term value and potential enhancements.

References

- 1. Weevers HJ, Van Der Beek AJ, Anema JR, Van Der Wal G, Van Mechelen W. Work-related disease in general practice: A systematic review. Fam Pract 2005;22:197-204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Verma B , Multani NK, Kundu ZS. Prevalence of shoulder pain among adults in Northern India. Asian J Health Med Res 2016;2:18-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Jain NB, Wilcox RB 3rd, Katz JN, Higgins LD. Clinical examination of the rotator cuff. PM R 2013;5:45-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Itoi E. Rotator cuff tear: Physical examination and conservative treatment. J Orthop Sci 2013;18:197-204. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Holmgren T, Hallgren HB, Oberg B, Adolfsson L, Johansson K. Effect of specific exercise strategy on need for surgery in patients with subacromial impingement syndrome: Randomised controlled study. Br J Sports Med 2014;48:1456-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Wagh N, Maniar A, Fuse A, Apte A, Bharadwaj S. Functional outcome in patients undergoing arthroscopic single row repair of rotator cuff tears. MVP J Med Sci 2021;7:60-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Lorbach O, Bachelier F, Vees J, Kohn D, Pape D. Cyclic loading of rotator cuff reconstructions: Single-row repair with modified suture configurations versus double-row repair. Am J Sports Med 2008;36:1504-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Xu C, Zhao J, Li D. Meta-analysis comparing single-row and double-row repair techniques in the arthroscopic treatment of rotator cuff tears. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23:182-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Chen M, Xu W, Dong Q, Huang Q, Xie Z, Mao Y. Outcomes of single-row versus double-row arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis of current evidence. Arthroscopy 2013;29:1437-49. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Millett PJ, Warth RJ, Dornan GJ, Lee JT, Spiegl UJ. Clinical and structural outcomes after arthroscopic single-row versus double-row rotator cuff repair: A systematic review and meta-analysis of level I randomized clinical trials. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23:586-97. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Sheibani-Rad S, Giveans MR, Arnoczky SP, Bedi A. Arthroscopic single-row versus double-row rotator cuff repair: A meta-analysis of the randomized clinical trials. Arthroscopy 2013;29:343-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Yadav N, Devgan A, Yadav U, Kumar R, Tiwari C, Siwach R, et al. A retrospective study to evaluate functional outcome after arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using single-row technique. Int J Acad Med Pharm 2023;5:664-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Vasu Bangera V, Bhandary B, Bhandary S, Hegde RM, Shabir Kassim M. Evaluation of clinical and functional outcomes of arthroscopic single row rotator cuff repair in our institution; a retrospective study. Indian J Orthop Surg 2019;5:15-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Davey MS, Hurley ET, Carroll PJ, Galbraith JG, Shannon F, Kaar K, et al. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair results in improved clinical outcomes and low revision rates at 10-year follow-up: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2023;39:452-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Wolf EM, Pennington WT, Agrawal V. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair: 4- to 10-year results. Arthroscopy 2004;20:5-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Leggin BG, Michener LA, Shaffer MA, Brenneman SK, Iannotti JP, Williams GR Jr. The Penn shoulder score: Reliability and validity. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 2006;36:138-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Jadhav PD, Kalyan HK, Shanthakumar S, Arya S, Harshavardhana V, Ajay Kuar SP. Functional outcome following arthroscopic rotator cuff repair with single row technique using bio absorbable anchors: Prospective study. Int J Orthop Sci 2019;5:334-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Kobayashi T, Shitara H, Osawa T. Factors involved in the presence of symptoms associated with rotator cuff tears: A comparison of asymptomatic and symptomatic rotator cuff tears in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2011;20:1133-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Yamamoto A, Takagishi K, Osawa T, Yanagawa T, Nakajima D, Shitara H, et al. Prevalence and risk factors of a rotator cuff tear in the general population. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:116-20. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Fossati C, Stoppani C, Menon A, Pierannunzii L, Compagnoni R, Randelli PS. Arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in patients over 70 years of age: A systematic review. J Orthop Traumatol 2021;22:3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Longo UG, Carnevale A, Piergentili I, Berton A, Candela V, Schena E, et al. Retear rates after rotator cuff surgery: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2021;22:749. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Kamat N, Parikh A, Agrawal P. Evaluation of functional outcome of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair using southern California orthopedic institute technique. Indian J Orthop 2019;53:396-401. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Vamsinath P, Ballal M, Prakashappa TH, Kumar S. A study of functional outcome of arthroscopic rotator cuff repair in rotator cuff tear patients. Indian J Orthop Surg 2018;4:204-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Jacob RV, Girotra P, Prashanth Kumar K. Arthroscopic repair of rotator cuff tears: Analysis and functional outcome. Int J Res Orthop 2020;6:256-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Park JG, Cho NS, Song JH, Baek JH, Jeong HY, Rhee YG. Rotator cuff repair in patients over 75 years of age: Clinical outcome and repair integrity. Clin Orthop Surg 2016;8:420-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Kim DH, Elattrache NS, Tibone JE, Jun BJ, DeLaMora SN, Kvitne RS, et al. Biomechanical comparison of a single-row versus double-row suture anchor technique for rotator cuff repair. Am J Sports Med 2006;34:407-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Rush LN, Savoie FH, Itoi E. Double-row rotator cuff repair yields improved tendon structural integrity, but no difference in clinical outcomes compared with single-row and triple-row repair: A systematic review. J ISAKOS 2017;2:260-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Galanopoulos I, Ilias A, Karliaftis K, Papadopoulos D, Ashwood N. The impact of re-tear on the clinical outcome after rotator cuff repair using open or arthroscopic techniques – a systematic review. Open Orthop J 2017;11:95-107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]