This case is interesting in view of the etiology, as it is rarely taken into account in clinical differentiation. Review of literature suggests that the possibility of such etiology is very rare and has not been reported. However, as a single-case report, the findings cannot be generalized and carry inherent limitations in terms of wider applicability or statistical validation.

Dr. Pratik Sunil Tawri, Department of Orthopaedics, Bombay Hospital Institute of Medical Sciences, Mumbai, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: tawripratik@gmail.com

Introduction: Pancreatic injuries resulting from trauma in cases involving spine fractures are extremely rare and often go unnoticed, particularly in patients with complex polytrauma. A literature search did not yield any similar reported cases.

Case Report: A 50-year-old male presented with polytrauma, including pelvis and spine fractures, post-traumatic pancreatitis, and a pseudoaneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery (SMA). The patient underwent open reduction and internal fixation for the fractures, followed by conservative management for pancreatitis. The pseudoaneurysm, identified through digital subtraction angiography, was treated with microcatheterization and micro-coiling in an interventional suite. The case presented unique challenges, successfully managed with a multidisciplinary approach.

Conclusion: Severely injured polytrauma patients demand a multidisciplinary approach, advanced expertise, and state-of-the-art facilities. This case highlights a rare post-traumatic pancreatitis with SMA pseudoaneurysm, successfully managed alongside spine and pelvis fractures.

Keywords: Polytrauma, post-traumatic pancreatitis, superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm, spine and pelvic fractures, multidisciplinary approach.

Pancreatic injuries resulting from trauma in cases involving spine fractures are extremely rare and often go unnoticed, particularly in patients with complex polytrauma. Serum amylase and lipase, which are markers for post-traumatic pancreatitis, exhibit changes that are time-dependent, and abnormalities, may not appear for several hours post-injury. A delayed diagnosis of pancreatic injuries increases the risk of morbidity and mortality. Although splenic artery pseudoaneurysms are recognized complications in trauma cases, pseudoaneurysms involving the superior mesenteric artery (SMA) are exceedingly uncommon. A literature search did not yield any similar reported cases. The literature search was performed using PubMed, Scopus, and Google Scholar databases with keywords “post-traumatic pancreatitis,” “superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm,” “spine fracture,” and “pelvic fracture” for the period 1990–2023.

A 50-year-old male was admitted following a fall from a height of approximately 10 feet at a construction site, resulting in spine and pelvic fractures. He initially received care at a local hospital for hemorrhagic shock before being transferred to our tertiary care center via air ambulance 2 days later. On arrival, the patient was conscious but remained hemodynamically unstable due to hypovolemic shock, which was managed in the intensive care unit (ICU). A thorough evaluation, including scans, revealed multiple injuries: A right sacral ala fracture, D6 and L1 burst fractures, right transverse process fractures of several lumbar vertebrae, pubic diastasis with a right anterior column fracture, as well as fractures of the right medial clavicle and the right seventh rib (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Right sacral ala fracture (Dennis type 2) and pubic diastasis with right anterior column fracture.

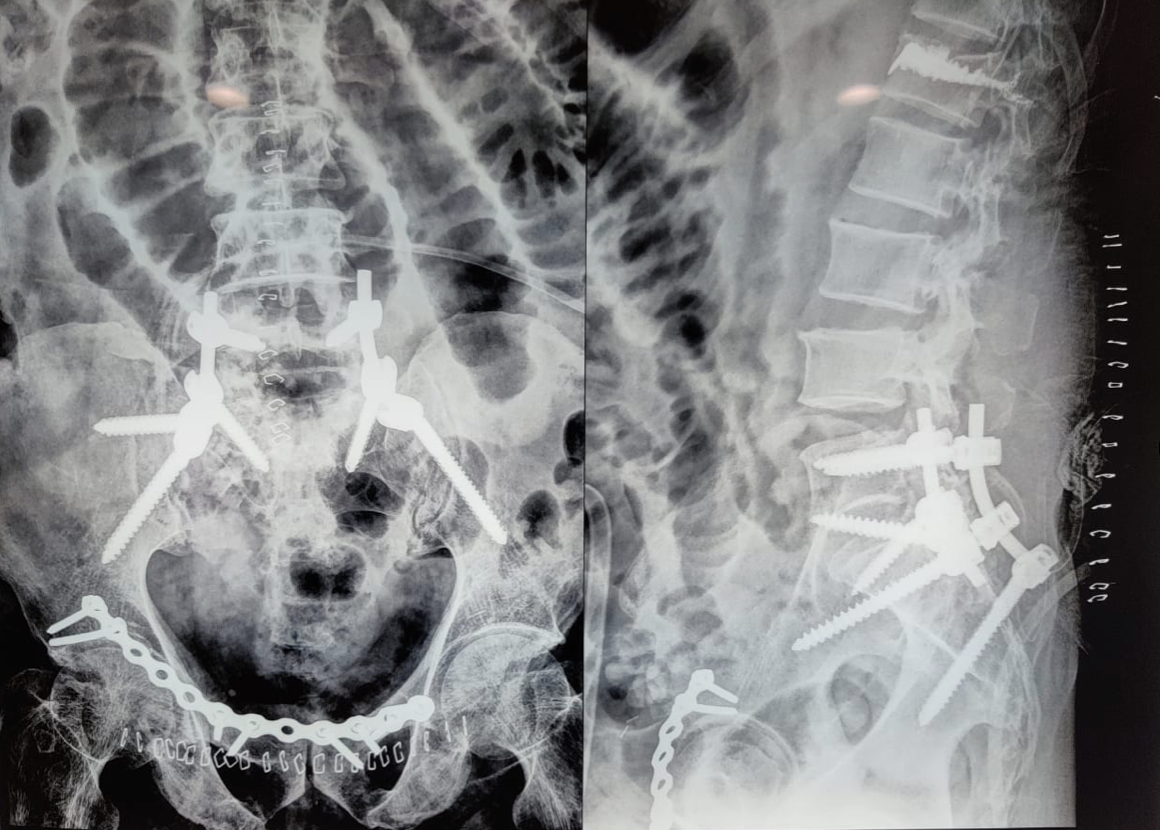

In addition, a Morel-Lavallée lesion was noted near the right kidney and was subsequently debrided with a drain in place. Initial ultrasound imaging of the abdomen revealed minimal free fluid, and the patient was stabilized with hemoglobin levels raised to 10 g/dL. Surgical intervention began with stabilization of the spine through open reduction and internal lumbo-pelvic fixation. The patient was then repositioned to fix the right acetabular fracture using a modified Stoppa approach (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Post-operative X-ray of lumbopelvic fixation (L5-Iliac); L1 vertebroplasty; Right acetabulum anterior column open reduction internal fixation with 14-hole Recon plate.

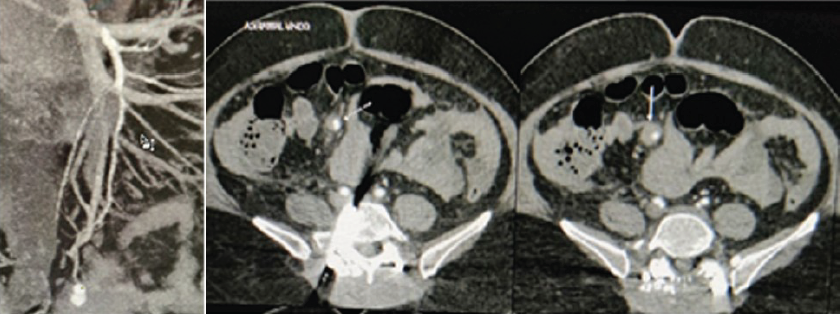

The procedure was successful, and the patient was monitored postoperatively. Two days after surgery, the patient developed acute pancreatitis, presenting with abdominal pain, vomiting, and elevated serum lipase levels (743 U/L, rising to 6231 U/L). Although the pancreas was obscured on ultrasound due to excessive bowel gas, the condition was managed conservatively, and the pancreatitis subsided within 6 days. Serial laboratory monitoring showed a rise in serum lipase from 743 U/L to 6231 U/L, followed by a gradual decline over the next week. Leukocytosis and inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein were tracked and correlated with clinical recovery. The limited resolution of ultrasound due to bowel gas delayed clear visualization of the pancreas, and high-resolution imaging (such as early computed tomography [CT]) was not performed initially, which may have contributed to the diagnostic delay. On postoperative day 9, the patient experienced fever, tachycardia, and leukocytosis. Suspected causes included central venous catheter-related sepsis or a surgical site infection, though wound examination and blood cultures showed no signs of infection. Chest imaging revealed a right-sided pleural effusion, for which pleural tapping was performed, providing temporary relief. However, the patient’s condition worsened on postoperative day 12, with hypotension, breathlessness, and desaturation. Following a cardiology evaluation and a CT angiography, a vaso-vagal event was suspected. A gastroenterological review was initiated after the patient developed severe abdominal distension, vomiting, and a significant drop in hemoglobin levels. CT angiography of the abdomen revealed hemoperitoneum and evidence of active bleeding, with contrast extravasation suggesting a pseudoaneurysm of the SMA (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Contrast-enhanced CT scan shows the pseudoaneurysm (white arrow) in one of the distal branch of the superior mesenteric artery

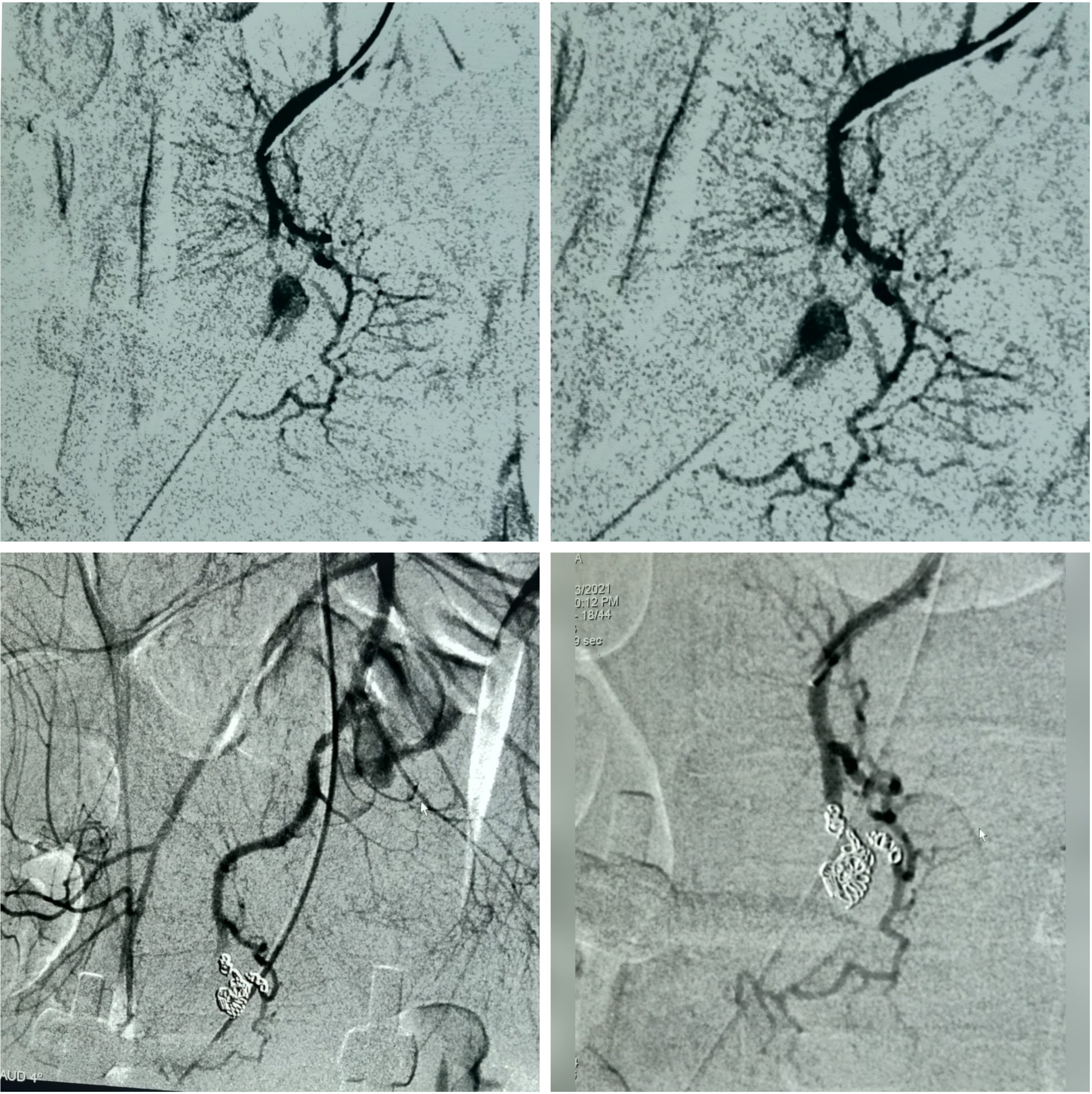

An urgent digital subtraction angiography confirmed the pseudoaneurysm, and selective catheterization of the affected artery was performed, followed by embolization using micro-coils. Post-procedure, the patient showed marked improvement, and hemoglobin levels were restored through multiple transfusions (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Exclusion of the pseudoaneurysm is confirmed by selective SMA injection after coil deployment.

The patient required four units of packed red blood cells perioperatively and was managed in ICU with fluid resuscitation, analgesia, and nutritional support. Criteria for interventional versus conservative management were based on hemodynamic stability, imaging findings, and ongoing blood loss. By post-operative day 16, the patient’s surgical wounds had healed, and he was discharged in a stable condition. At a 3-month follow-up and now again at 3-year follow-up, the patient reported no recurrence of symptoms and has regained complete mobility. At the 3-year review, pancreatic enzyme levels were normal, vascular imaging showed no recurrence of pseudoaneurysm, and the patient reported good quality of life with complete return to work and daily activities.

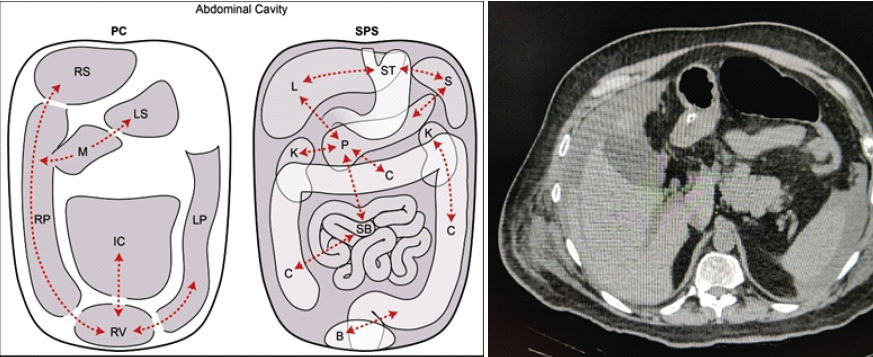

This case presented a unique diagnostic challenge, highlighting a delayed presentation of post-traumatic pancreatitis associated with a SMA pseudoaneurysm in a patient with spine and pelvic fractures. However, the causal linkage between trauma, pancreatitis, and the pseudoaneurysm remains largely inferential, as direct pathophysiological confirmation is not feasible in this setting. Trauma patients, particularly those with multiple injuries, require comprehensive imaging to rule out internal injuries that may not be immediately apparent through physical examination [1]. No comparative group (such as similar polytrauma patients without pancreatic injury) was available, limiting the contextualization of the rarity or clinical course. Pelvic fractures are a common cause of hemorrhagic shock in blunt trauma cases, with mortality rates as high as 30% in patients who present in shock [2,3]. The severity of pelvic and spine fractures correlates with the extent of energy transfer during trauma, requiring careful triage and early intervention to control blood loss [4]. Pancreatic injuries, although uncommon, carry significant risks when they occur in conjunction with other intra-abdominal injuries. The retroperitoneal location of the pancreas makes it difficult to detect injuries early, often resulting in delayed diagnosis and treatment. A high degree of clinical suspicion is necessary to prevent missed pancreatic trauma, especially in polytrauma patients [5]. In cases of pancreatic injury, non-operative management is typically preferred for lower-grade injuries, while higher-grade injuries may require surgical intervention [6,7]. Imaging, particularly CT, plays a critical role in diagnosing pancreatic trauma, as ultrasound findings can be subtle and unreliable. Pseudoaneurysms of the SMA are rare, accounting for only 5.5% of all visceral artery aneurysms. They are often caused by trauma and can lead to life-threatening complications if not identified and treated promptly [8,9]. Angioembolization is the preferred treatment method for SMA pseudoaneurysms due to its lower risk profile and quicker recovery time compared to open surgery [10] (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: The peritoneal cavity (PC) versus the subperitoneal space (SPS). This is a schematic diagram showing the PC on the left and the SPS on the right. Dotted lines show some of these interconnections which allow for disease spread. Abbreviations: IC: Inframesocolic compartment, LP: Left paracolic recess, LS: Lesser sac, M: Morison’s pouch, RP: Right paracolic recess, RS: Right subphrenic space, and RV: Rectovesical space, B: Bladder, C: Colon, K: Kidney, L: Liver, P: Pancreas, S: Spleen, SB: Small bowel, and ST: Stomach [10].

Limitations

This report may be subject to reporting bias, as unusual and successful cases are more likely to be published than negative outcomes. In addition, the management pathway required tertiary-care facilities and advanced interventional radiology, which may not be available in many trauma settings, limiting external applicability.

This case underscores the importance of early suspicion and multidisciplinary care in managing complex trauma patients. The rare complication of a SMA pseudoaneurysm in the context of post-traumatic pancreatitis highlights the need for advanced diagnostic tools and expert intervention. A review of the literature indicates that such cases are exceedingly rare, making this a significant contribution to the understanding and management of traumatic pancreatic injuries.

This case underscores the importance of early suspicion and multidisciplinary care in managing complex trauma patients.

References

- 1. Lee C, Porter K. The prehospital management of pelvic fractures. Emerg Med J 2007;24:130-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Okada Y, Nishioka N, Ohtsuru S, Tsujimoto Y. Diagnostic accuracy of physical examination for detecting pelvic fractures among blunt trauma patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. World J Emerg Surg 2020;15:56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. ATLS Subcommittee, American College of Surgeons’ Committee on Trauma, International ATLS working group. Advanced trauma life support (ATLS®): The ninth edition. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2013;74:1363-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Sauerland S, Bouillon B, Rixen D, Raum MR, Koy T, Neugebauer EA. The reliability of clinical examination in detecting pelvic fractures in blunt trauma patients: A meta-analysis. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2004;124:123-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Debi U, Kaur R, Prasad KK, Sinha SK, Sinha A, Singh K. Pancreatic trauma: A concise review. World J Gastroenterol 2013;19:9003-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Wilson RH, Moorehead RJ. Current management of trauma to the pancreas. Br J Surg 1991;78:1196-202. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Fisher M, Brasel K. Evolving management of pancreatic injury. Curr Opin Crit Care 2011;17:613-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Ray B, Kuhan G, Johnson B, Nicholson AA, Ettles DF. Superior mesenteric artery pseudoaneurysm associated with celiac axis occlusion treated using endovascular techniques. Cardiovasc Intervent Radiol 2006;29:886-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Zimmerman-Klima PM, Wixon CL, Bogey WM Jr., Lalikos JF, Powell CS. Considerations in the management of aneurysms of the superior mesenteric artery. Ann Vasc Surg 2000;14:410-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Zeebregts CJ, Cohen RA, Geelkerken RH. Posttraumatic dissecting aneurysm of the superior mesenteric artery. Am J Surg 2004;187:98-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]