Young adults with multiple joints pain or restricted movement, especially those with a history of steroid use, should be evaluated for MSON. Tensor fascia lata muscle pedicle grafting (TFLMPG) can be considered the primary surgery in hips to avoid the need for a second surgery.

Dr. B Sai Theja, Department of Orthopaedics, Manipal Hospital, Bengaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: saitheja.ortho@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteonecrosis (ON) refers to the death of bone cells caused by a disruption in blood flow. Multiple-site osteonecrosis (MSON) is a rare condition characterized by concurrent or sequential involvement of three or more separate anatomic sites approximately 3% of ON patients. Avascular necrosis (AVN) is commonly associated with high-dose or long-term corticosteroid use, and several reports suggest that high-dose corticosteroid use is the primary risk factor for developing MSON. The ideal management of ON in a young individual remains a subject of debate. Review of literature supports Core decompression (CD) as an effective treatment option in the pre-collapse stage of ON in small to medium-sized lesions according to Ficat and Arlet Stage I and II. In the advanced stages of the disease (i.e., Stages III and IV), arthroplasty is required when joint preservation is not possible.

Case Report: A 27-year-old female presented with pain in the right ankle and left shoulder. The patient was on corticosteroids. Suspected MSON by examination was later confirmed using magnetic resonance imaging. CD and bone marrow aspiration concentrate application sequentially in all affected joints in three sessions with a 2-month gap. Alendronate 70 mg once a week is advised. Tensor fascia lata muscle pedicle bone grafting was performed on both hips following two years post-primary surgery due to the continued progression of the disease.

Conclusion: Therefore, young adults experiencing pain or a limited range of motion in their shoulder and ankle joints, particularly if they have a history of steroid use and no other known causes, should be checked for MSON. CD, Bone marrow aspirate concentrate application, and alendronate have decreased the rate of progression of the disease in all joints except in the hips. Tensor fascia lata muscle pedicle grafting decreased progression in the hips.

Keywords: Multiple site osteonecrosis, Tensor fascia lata muscle pedicle grafting, corticosteroids, core decompression, bone marrow aspiration concentrate.

Osteonecrosis (ON) refers to the death of bone cells caused by a disruption in blood flow, leading to pain, deterioration of bone structure, and decline in functionality. It is a debilitating disorder that commonly affects younger individuals, typically those between 20 and 50 years of age. Multiple site osteonecrosis (MSON) is a rare condition characterized by concurrent or sequential involvement of three or more separate anatomic sites [1]. It has been reported in approximately 3% of ON patients [2]. Avascular necrosis (AVN) is commonly associated with high-dose or long-term corticosteroid use[3], and several reports suggest that high-dose corticosteroid use is the primary risk factor for developing MSON. Other risk factors include systemic lupus erythematosus, human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) infection, coagulation disorders (antithrombin III deficiency, protein S deficiency, factor V Leiden gene mutation, and heightened activity of the plasminogen activator), renal failure, inflammatory bowel diseases, multiple sclerosis, Sjogren’s syndrome, sickle cell disease, as well as leukemia and lymphoma [4]. No prior trigger is known in 40% of cases, and the condition is then considered idiopathic. MSON is often asymptomatic, making diagnosis challenging, and the exact incidence among patients with various diseases remains unclear [4]. Guillain-Barré syndrome (GBS) is the most common cause of acute, flaccid, neuromuscular paralysis [5]. In the last 10 years of literature review, there has been only one report of the association between GBS and MSON [6]. Here, we report a rare case demonstrating a patient with a history of corticosteroid use for GBS presenting with MSON. The patient gave her consent after being told that information about the case will be submitted for publication.

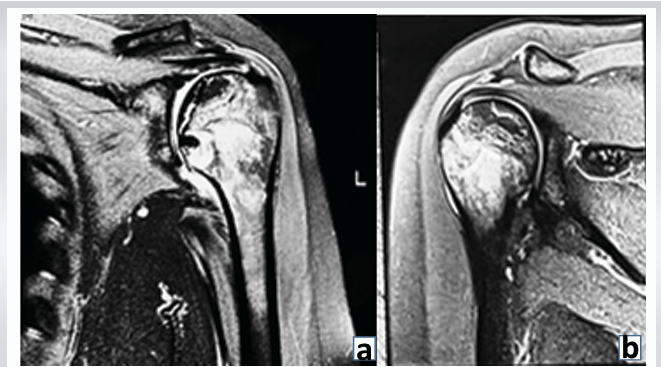

A 27-year-old female presented with chief complaints of pain and swelling in her right ankle for 8 months and in her left shoulder for 4 months. The pain started spontaneously and was gradually progressive. The patient had no history of trauma. Two years before the onset of symptoms, the patient had a history of GBS for which the patient took intravenous (IV) immunoglobulins for 4 days, IV steroids for 1 week, followed by oral steroids for 3 months. Examination of all individual joints was done under suspicion of MSON and revealed tenderness in both shoulders with limited internal rotation on the left (four vertebral levels down). Both hips showed joint line tenderness with painful terminal degrees of range of motion (ROM). The right knee had lateral joint line tenderness and painful terminal degrees of flexion, while the left knee was clinically normal. The right ankle had anterior joint line tenderness and painful terminal dorsiflexion; the left ankle was normal. Radiological studies showed ON of both humeral heads (Cruess stage – 2 [7]) with greater involvement on the left side (Fig. 1a and b).

Figure 1a & b: Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging both shoulders. 1.5. T. Proton density (PD) fat saturation, coronal images showing irregular, serpiginous PD hyperintensities in proximal humerus, Left (a) > Right (b), humerus contour and joint space maintained. Suggestive of avascular necrosis of both humeral heads (Cruess-II).

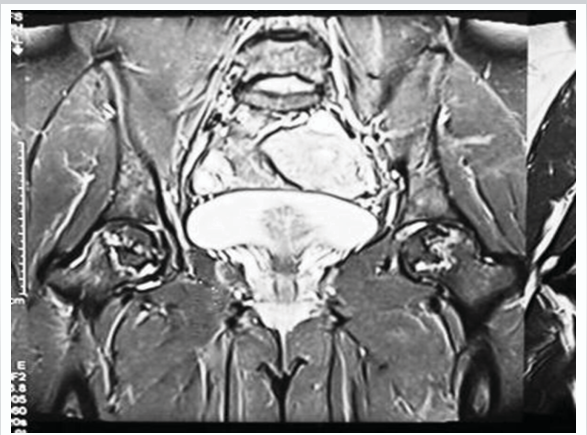

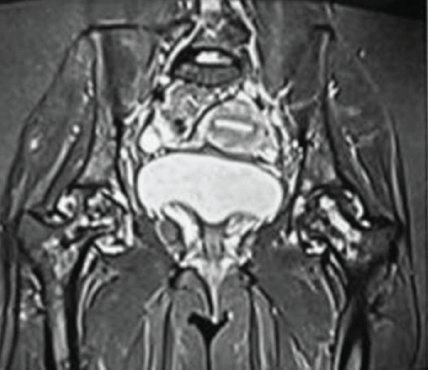

There was bilateral ON of the hips (stage 2 of Ficat-Arlet classification [8]) with greater involvement of the right femoral head than the left (Fig. 2).

Figure 2: Pre op MRI both hips. 1.5 T. Short tau inversion recovery coronal image showing ill defined geographic hyperintensities (right > left) in femoral head, femoral contour, and joint space maintained. Suggestive of avascular necrosis of both femoral heads (Ficat-Arlet II) (Right > Left).

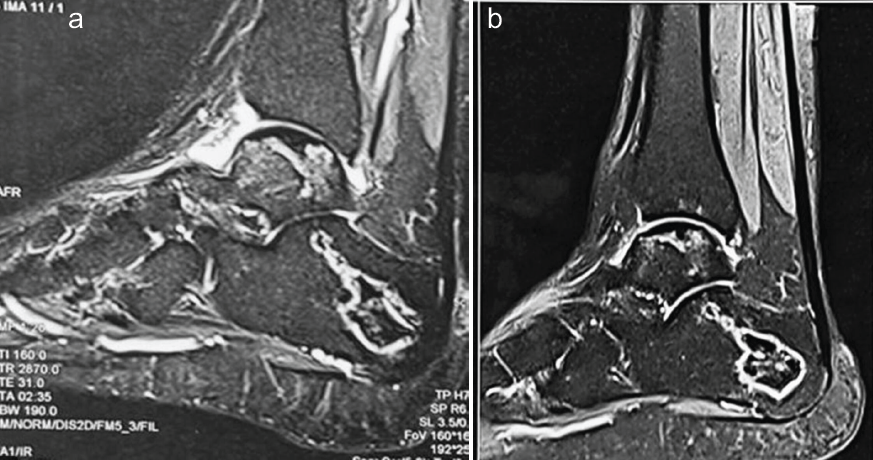

There was bilateral stage-2 involvement of the navicular, calcaneum, and talus, again with the right side being more affected than the left (Fig. 3a and b). Both knees were also classified as stage 2, with the right knee showing more severity than the left (Fig. 4a and b).

Figure 3: Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging both ankles. 1.5 T. Proton density fat saturation sagittal images showing irregular, serpiginous hyperintensities in bilateral calcaneum, navicular, and talus (right (A) > left (B)), suggestive of bone infarcts with maintenance of contours of talar domes, calcanei, and tali.

Figure 4: Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging both knees. 1.5 T. Proton density fat saturation Coronal images showing irregular, serpiginous hyperintensities in both knees involving distal femur and proximal tibia (Right (A) > Left (L)), suggestive of bone infarcts with maintenance of contour of bilateral distal femur and proximal tibia.

With these findings, a diagnosis of MSON was made. Investigations were conducted to exclude underlying conditions commonly associated with MSON, which included an evaluation for connective tissue diseases: Complete blood count, erythrocyte sedimentation rate, C-reactive protein, renal function test, rheumatoid arthritis factor, anti-nuclear antibodies, anti-ds DNA, lupus anticoagulant, and anticardiolipin antibodies; an assessment of coagulation profile: Prothrombin time, activated partial thromboplastin time, international normalized ratio, fibrinogen, antithrombin, protein C, protein S, factor V Leiden, and factor VIII; and testing for viral markers (HIV, Hepatitis B virus, Hepatitis C virus), all of which returned negative results, thereby ruling out any underlying diseases. The patient’s history ruled out drug usage, alcohol usage, and exposure to hyperbaric environments (eliminating Caisson’s disease). She underwent core decompression and bone marrow aspiration concentrate (CD and BMAC) application sequentially in all affected joints in 3 sessions with a 2-month gap. Shoulders were first addressed, and knees and ankles were addressed last, and advised Alendronate 70 mg once a week after shoulder surgery for 3 years. When evaluated after 18 months of surgery, the pain Visual Analog Scale (VAS) in the shoulder decreased from 9/10 to 0/10 (Fig. 1c). In the hips, VAS of 6/10 decreased to 0/10 after 1 month of surgery. But after 9 months, it gradually increased to 9/10. Radiological assessments indicated that both hips advanced to Stage III, with the right hip showing a greater deterioration than the left (Fig. 5). Thus, she underwent TFL muscle pedicle bone grafting to both hips after 2 years of primary surgery, following which VAS scores gradually decreased to 2/10 on the right side and 0/10 on the left side (Fig. 6). VAS decreased from 9/10 to 4/10 in the right ankle and from 9/10 to 4/10 in the right knee. The left ankle and knee remained pain-free in both pre-operative and post-operative periods. The patient is walking independently now.

Figure 5: Magnetic resonance imaging of both hips post-core decompression. 1.5 T. Short tau inversion recovery, coronal, showing heterogeneous hyperintense signals in both femoral heads with loss of contour of femoral heads (right > left) and joint space maintained, suggestive of Ficat-Arlet III stage of avascular necrosis. Stigmata of core decompression were seen at both femoral heads.

Figure 6: Digital X-ray of pelvis with both hips showing avascular necrosis of both femoral heads operated with tensor fascia lata muscle pedicle graft.

ON is believed to result from ischemia of the juxta-articular bone, usually occurring in the second through fifth decades [9]. According to the Collaborative ON Group Study, 91% of cases of MSON are caused by steroids [10]. Steroid dosage and route of administration appear to be closely related to the development of MSON. In our case, the major factor contributing to the MSON was prolonged corticosteroid use. In terms of anatomic distribution, MSON most commonly affects the femoral head, followed by the knee, shoulder, and ankle. In our case, the ankle and shoulder were affected first, followed by the remaining joints. Most patients have pain on the affected site, but up to 33% have asymptomatic ON. Magnetic resonance imaging is the gold standard diagnostic method to detect both symptomatic and silent ON [11] and is essential for assessing the severity of the disease and informing treatment strategies. The degree of epiphyseal involvement, categorized by various classifications as <15%, between 15% and 30%, or exceeding 30% of the epiphyseal volume, serves as the most reliable indicator of potential bone collapse [12]. The advancement of ON can vary significantly among different joints. Notably, the femoral head tends to progress at a rapid pace, necessitating careful monitoring for the early onset of symptoms. In contrast, the progression in the elbow and wrist occurs at a comparatively slower rate [4]. The ideal management of ON in a young individual remains a subject of debate. Typically, conservative approaches are employed when there is no indication of joint collapse, such as the use of non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs (NSAIDs) and limiting weight-bearing activities. In addition, various surgical interventions have been suggested based on the disease’s progression. These interventions encompass CD, both vascularized and non-vascularized grafting, osteotomy, and ultimately, arthroplasty as a last resort [13]. It is essential for patients to undergo follow-up assessments for 2 years to evaluate the condition of the adjacent joint and to consider total joint replacement if necessary. Review of literature supports CD as an effective treatment option in the pre-collapse stage of ON in small to medium-sized lesions according to Ficat and Arlet Stage-I and II [14]. In the advanced stages of the disease (i.e., Stages III and IV), arthroplasty is required when joint preservation is not possible [4]. A recent systematic review on CD showed 78%, 59%, and 27% success rates in Stages I, II, and III, respectively [15]. Alendronate is the preferred medication for this relentlessly progressive condition, irrespective of the stage at which patients are diagnosed, as it alters the natural progression of AVN of the hips and delays the necessity for arthroplasty [16]. Hence, we advised taking sodium Alendronate 70 mg once a week. In this case, CD and BMAC were done as all the joints were in Stage II. Post-surgery, the shoulder joints are pain-free. She is experiencing intermittent pain in her hip joints twice or thrice a month, which can be managed with NSAIDs. VAS scores for both hips improved within a month of surgery, yet after 9 months, the score increased as both hips progressed to stage III. This suggests CD and BMAC was unsuccessful. We can infer that, as her condition improved drastically after the second surgery, TFLMPG, it would have been better to perform it instead of CD and BMAC. This would have avoided the need to perform a second surgery. Her right knee and ankle pains only on walking for prolonged periods of time, which can be controlled by NSAIDs. Now she is able to walk independently, do her daily activities, and her overall quality of life has improved significantly.

Young adults experiencing pain or limited ROM in their shoulder and ankle joints, particularly if they have used steroids in the past and there are no other known causes, should be checked for MSON. A young patient with AVN in more than six locations is a rare occurrence, which makes this case very challenging. The MSON is probably linked to steroid use in this case. Combined CD, BMAC, and Alendronate can be an effective and safe method of treating MSON in all joints except hips. TFLMPG can be considered the primary surgery in hips to avoid the need for a second surgery. Hence, high-quality randomized controlled trials and prospective studies will be necessary to understand the effectiveness of this procedure more clearly.

Young adults experiencing pain or limited ROM in their shoulder and ankle joints, particularly if they have used steroids in the past and there are no other known causes, should be checked for MSON. Combined CD, BMAC, and Alendronate can be an effective and safe method of treating MSON in all joints except hips. TFLMPG can be considered the primary surgery in hips to avoid the need for a second surgery.

References

- 1. Collaborative Osteonecrosis Group. Symptomatic multifocal osteonecrosis. A multicenter study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;369:312-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. LaPorte DM, Mont MA, Mohan V, Jones LC, Hungerford DS. Multifocal osteonecrosis. J Rheumatol 1998;25:1968-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Nakamura J, Ohtori S, Sakamoto M, Chuma A, Abe I, Shimizu K. Development of new osteonecrosis in systemic lupus erythematosus patients in association with long-term corticosteroid therapy after disease recurrence. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2010;28:13-18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Sun W, Shi Z, Gao F, Wang B, Li Z. The pathogenesis of multifocal osteonecrosis. Sci Rep 2016;6:29576. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Govoni V, Granieri E. Epidemiology of the Guillain-Barré syndrome. Curr Opin Neurol 2001;14:605-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Aroso PM, Carvalho P, Amaral C, Pinheiro J. Multifocal osteonecrosis and Guillain Barré syndrome. Revista Da SPMFR 2019;31:32-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Cruess RL. Experience with steroid-induced avascular necrosis of the shoulder and etiologic considerations regarding osteonecrosis of the hip. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1978;130:86-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Jawad MU, Haleem AA, Scully SP. In brief: Ficat classification: Avascular necrosis of the femoral head. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:2636-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Assouline-Dayan Y, Chang C, Greenspan A, Shoenfeld Y, Gershwin ME. Pathogenesis and natural history of osteonecrosis. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2002;32:94-124. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Mont MA, Jones LC, LaPorte DM. Symptomatic multifocal osteonecrosis. A multicenter study. Collaborative osteonecrosis group. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1999;369:312-26. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Nagasawa K, Tada Y, Koarada S, Horiuchi T, Tsukamoto H, Murai K, et al. Very early development of steroid-associated osteonecrosis of femoral head in systemic lupus erythematosus: Prospective study by MRI. Lupus 2005;14:385-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Chang C, Greenspan A, Gershwin ME. Osteonecrosis. Kelley’s Textbook of Rheumatology. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2013. p. 1692-711. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Mudawi T, Mahto A, Ruffle JK, Bubbear J. Multi-site avascular necrosis of idiopathic aetiology. Rheumatol Adv Pract 2017;1 Suppl 1:rkx010.005 . October 2017, rkx010.005, https://doi.org/10 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Moon JG, Shetty GM, Biswal S, Shyam AK, Shon WY. Alcohol induced multifocal osteonecrosis: A case report with 14-year follow-up. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2008;128:1149-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Karimi M, Moharrami A, Vahedian Aedakani M, Mirghaderi SP, Ghadimi E, Mortazavi SJ. Predictors of core decompression success in patients with femoral head avascular necrosis. Arch Bone Jt Surg 2023;11:517-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Agarwala S, Shah SB. Ten-year follow-up of avascular necrosis of femoral head treated with alendronate for 3 years. J Arthroplasty 2011;26:1128-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]