TENS is a reliable and minimally invasive treatment for pediatric femoral shaft fractures, offering fast union, early weight-bearing, and excellent functional outcomes with minimal complications

Dr. Ismail Pandor, Department of Orthopedics, Krishna Vishwa Vidhyapeeth, Karad, Maharashtra, India. E-mail:i.pandor07@gmail.com

Introduction: Conservative management has always been used for pediatric fractures. However, surgical management has shown outstanding results. Closed reduction and titanium elastic nailing (TEN) is one of the procedures that is used for the management of pediatric injuries. We undertook this study to see the outcome of pediatric fractures treated with TEN.

Materials and Methods: A prospective study conducted at Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Karad. Thirty children with femoral fractures managed with TENs were included in this study. Patients were followed up till 12 months postoperatively for limb length discrepancy, pelvic asymmetries, rotational deformity, axial angulation, and hip and knee range of motion. Scoring criteria for TEN by Flynn et al. was used, and results were classified as excellent, satisfactory, or poor. Results: There were 19 boys and 11 girls in this study. The mean duration of surgery was 50 min. Radiological union was achieved in an average time of 7 weeks. Full weight bearing was achieved in a period of 7 weeks. As per the Flynn et al. criteria, the results were excellent in 24 patients, successful in 5, and poor in 1 patient. One patient had varus angulation, 3 patients had entry site irritation, and 2 had limb length discrepancy.

Conclusion: The TENS is an efficient and acceptable form of treatment in selected cases of femoral diaphyseal fractures in children.

Keywords: Pediatric femoral shaft, titanium, injuries, gold standard treatment.

The management of femoral fractures in pediatric age group (0–18 years) has always been a matter of debate. Several conservative as well as surgical treatments have been proposed [1]. However, the treatment of choice is typically based on the patient’s age, fracture type [2], associated injuries, and the physical characteristics of the child. Diaphysis fractures of the femur in children <6 years of age are usually treated with conservative methods, such as casting, tractions, or Pavlik harness [3]. These methods show good clinical and radiological results and represent the gold standard treatment [4]. However, conservative treatments are not suitable in specific cases such as polytraumatized patients, unstable fractures with risk of redisplacement, and difficulty in obtaining an acceptable reduction. Other concerns associated with conservative treatments such as the long hospitalization, the necessity of general anesthesia and treatment in the operating theater, prolonged weight-bearing restrictions, and the high cost have ignited an increasing interest in surgical management [5]. During the past few decades, some forms of internal fixation in the form of plate fixation, rigid intramedullary (IM) nailing, enders nailing, and titanium nailing have been advocated, but the controversy regarding the ideal implant still exists. For the age group of 6–16 years, which implant is superior to the other is still a matter of dilemma [6]. IM nailing with titanium elastic nails (TENs) offers several advantages, including early union, lower rate of malunion, spare of the physis, early mobilization and weight bearing, mini-invasive approach with easy implant removal, and high patients’ and parents’ satisfaction rates [7,8,9]. Good results at mid-term follow-up have been reported in children older than 6 years of age [10]. We undertook a prospective study to evaluate the outcome of pediatric femoral fractures managed with TENs.

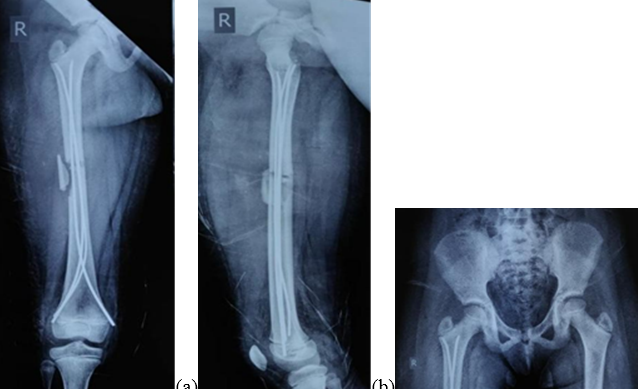

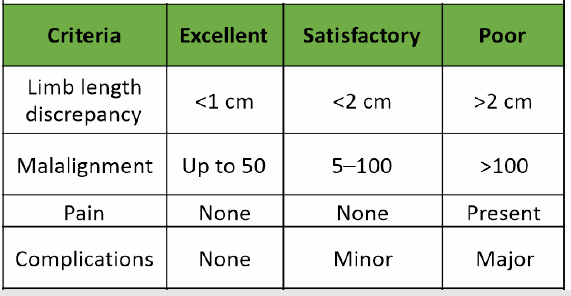

This was a prospective study conducted at Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Karad. The study was approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of Krishna Institute of Medical Sciences, Karad. Written informed consent was obtained from parents/guardians and assent from children when appropriate. Thirty children with femoral fractures managed with TENs were included in this study. Patients were followed up till 12 months postoperatively for limb length discrepancy, pelvic asymmetries, rotational deformity, axial angulation, and hip and knee range of motion. Scoring criteria for TEN by Flynn et al. [11] were used and results were classified as excellent, satisfactory, or poor (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Titanium elastic nailing.

Inclusion criteria

- Children aged 4–14 years with diaphyseal femoral shaft fractures

- Closed fractures or Gustilo type I-II open fractures

- Closed reduction is achievable or reducible under fluoroscopy.

Exclusion criteria

- Severe open fractures

- Pathological fractures

- Fractures extending into the proximal/distal physes (peri-articular fractures requiring other fixation)

- Associated ipsilateral femoral fractures or pelvic fractures preventing standard TENs fixation.

Pre-operative investigations

- Plain radiographs: Anteroposterior (AP) and lateral views of the femur, including hip and knee

- Routine blood tests: Complete blood count, coagulation profile, blood glucose, and basic biochemistry (urea, creatinine)

- Pre-anesthetic evaluation and fitness clearance

- Perioperative/follow-up investigations

- Intraoperative fluoroscopy to confirm reduction and nail position

- Postoperative radiographs (AP and lateral) immediately, at 2, 6, and 12 weeks, then at 6 and 12 months (or until union and hardware removal)

- Clinical assessment at each visit: Wound/entry site check, range of motion, limb length measurement, and assessment for complications.

Operative procedure

Traction was applied using a fracture table with the help of fluoroscopic guidance to reduce the fracture. Appropriately sized elastic nails of 2–3.5 mm diameter were selected. Elastic nails were bent in an even curve. The tip of the nail was further bent 2 cm from one end at an angle of 40°. This helps the nail to bounce off the opposite cortex into the canal rather than break it. After skin incision, insertion points were made one on the medial and another on the lateral side of the distal femur, 2 cm proximal to the distal epiphyseal plate. Elastic nails were pushed right up to the fracture site. Then one of the nails was passed across the reduced fracture site, which was followed by the second nail. The nails were directed in such a way that the medial nail was introduced into the neck and the lateral just below the trochanteric apophasis in a fan-shaped manner. Two divergent nails provide adequate fixation and stability in the adolescent femur [11,12]. The distal end of the nail should never project beyond the distal epiphyseal plate on IITV to prevent knee pain and problems of nail protrusion, and care should be taken to avoid pending the distal end of nails. Knee bending and quadriceps exercises were begun as soon as the patient could tolerate them. Non-weight bearing ambulation was started within first few days, though partial weight bearing was permitted only after radiological evidence of callus formation. Full weight bearing was allowed only on radiological evidence of a firm union (Fig. 2, 3, 4).

Figure 2: (a and b) Pre-operative anteroposterior and lateral radiographs.

Figure 3: (a, b, c) Three months postoperatively (anteroposterior (AP), pelvis and both hips -AP and lateral).

Figure 4: (a and b) Clinical photos at 3-month follow-up.

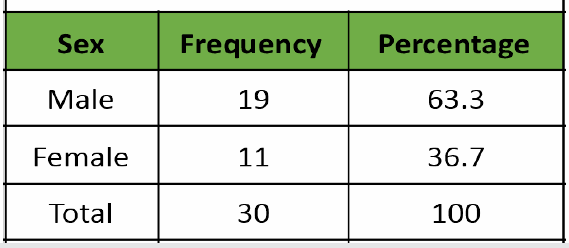

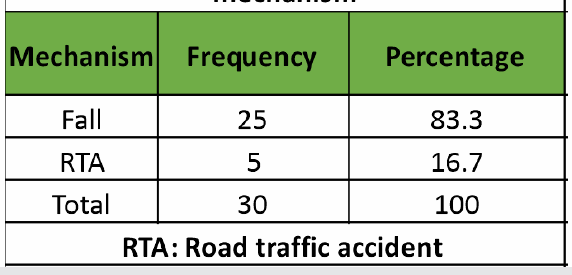

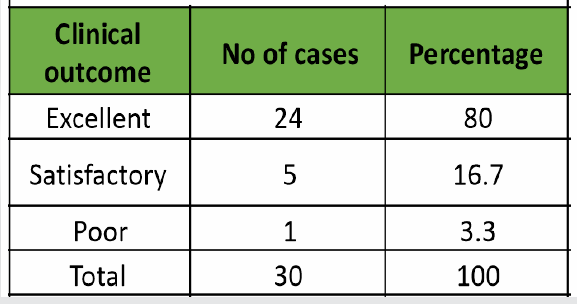

Ages of children ranged from 4 to 14 years (mean 8 years). There were 19 boys and 11 girls. 25 of the cases had fractures due to a fall from height, and 5 due to a road traffic accident. The mean duration of surgery was 50 min, and the average hospital stay was 7 days. All patients were available for evaluation after 12 months of follow-up. Radiological union was achieved in an average time of 7 weeks. Full weight bearing was achieved in a meantime of 7 weeks. As per the Flynn et al.’s [11] criteria, the results were excellent in 24 patients, successful in 5, and poor in 1 patient. One patient had varus angulation, 3 patients had entry site irritation, and 2 had limb length discrepancy. Functional range of movement was achieved within a mean duration of 8 weeks. Out of 30 cases, 10 had spiral fractures, 5 had oblique fractures, 8 had transverse and 7 had comminuted fractures. No post-operative difference was observed due to fracture pattern; hence, this signifies remodeling of the bone in this age group (Table 1, 2, 3, 4).

Table 1: Flynn et al. [11] criterion for assessment of results

Table 2: Frequency and percentage of respondents

Table 3: Frequency and percentage of mechanism

Table 4: Clinical outcome

Femoral shaft fractures constitute about 2% of pediatric injuries. Ample modalities have been suggested for its management, and they include plates, external fixators, IM nails, and TENs. Widely used plate osteosynthesis is associated with larger dissections, longer time of immobilization, increased risk of infection, and delayed union [13,14]. The external fixator has risks of pin track infection and generally takes longer for weight bearing to be started [15,16]. As far as IM nails are concerned, they have been associated with avascular necrosis of the femoral head, coxa valga [17,18]. TENs appears beneficial over other surgical methods, particularly in this age group, because it is simple, is a load-sharing internal splint that does not disrupt open physis, permits early mobilization, and maintains alignment at the fracture site, imitated by the elasticity of the fixation, and promotes faster external bridging callus formation. The periosteum is not troubled, and being a closed procedure, there is no disturbance of fracture hematoma thereby decreasing the risk of infection. In a study conducted by Flynn et al., [11] they found TENs was beneficial over hip spica in the treatment of femoral shaft fractures in children [6]. In another study, Buechsenschuetz et al. [19] came to the conclusion that the titanium nail was superior in terms of union, scar acceptance, and overall patient satisfaction compared to conservative management. Likewise, Ligier et al. [20] treated 123 femoral shaft fractures with elastic IM nail. In that study, all fractures united. Entry site irritation developed in 13 cases. Lascombes et al. [21] stated that TENs could be indicated in all femoral diaphyseal fractures of children with an age of more than 6 years till the epiphysis closed, excluding severe Type III open fractures. Narayanan et al. [9] found a good outcome in 79 femoral fractures stabilized with TENs. Despite the wide base of literature showing TENs as an efficient procedure [22], it comes with complications such as entry site irritation, pain, limb length discrepancy, fracture angulation, refractures, and infection. Entry site irritation and pain are the most common complications of TENs [9,11]. Entry site irritation was noted in cases where longer nails were used, and shorter nails led to angulation of the fracture. In this study, we had 3 cases with entry site irritation, 2 had LLD, and 1 had varus angulation. We conclude by saying that the advantages of TENs are in rehabilitation and healing with abundant callus, which is attributed to the non-rigid fixation achieved with it. This results in quick fracture union and timely return to full weight bearing while considerably dropping hospital stay and treatment charges. In addition, the choice of treatment with flexible nailing receives greater acceptance in the younger age group [23].

The TENs is an efficient and acceptable form of treatment in selected cases of femoral diaphyseal fractures in children.

TEN is a safe and effective option for treating pediatric femoral shaft fractures. It allows early mobilization, quick union, and excellent functional recovery with few complications, making it a reliable choice in children over 6 years of age.

References

- 1. Buckley SL. Current trends in the treatment of femoral shaft fractures in children and adolescents. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1997;338:60-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Slongo TF, Audigé L, AO Pediatric Classification Group. Fracture and dislocation classification compendium for children: The AO pediatric comprehensive classification of long bone fractures (PCCF). J Orthop Trauma 2007;21:S135-60. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Podeszwa DA, Mooney JF, Cramer KE 3rd, Mendelow MJ. Comparison of Pavlik harness application and immediate spica casting for femur fractures in infants. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:460-2. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Catena N, Sénès FM, Riganti S, Boero S. Diaphyseal femoral fractures below the age of six years: Results of plaster application and long term followup. Indian J Orthop 2014;48:30-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Madhuri V, Dutt V, Gahukamble AD, Tharyan P. Interventions for treating femoral shaft fractures in children and adolescents. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2014;2014:CD009076. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Flynn JM, Luedtke LM, Ganley TJ, Dawson J, Davidson RS, Dormans JP, et al. Comparison of titanium elastic nails with traction and a spica cast to treat femoral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2004;86:770-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Hunter JB. The principles of elastic stable intramedullary nailing in children. Injury 2005;36 Suppl 1:A20-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Bhaskar A. Treatment of long bone fractures in children by flexible titanium elastic nails. Indian J Orthop 2005;39:166-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Narayanan UG, Hyman JE, Wainwright AM, Rang M, Alman BA. Complications of elastic stable intramedullary nail fixation of pediatric femoral fractures, and how to avoid them. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:363-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Saikia K, Bhuyan S, Bhattacharya T, Saikia S. Titanium elastic nailing in femoral diaphyseal fractures of children in 6-16 years of age. Indian J Orthop 2007;41:381-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Flynn JM, Hresko T, Reynolds RA, Blasier RD, Davidson R, Kasser J. Titanium elastic nails for pediatric femur fractures: A multicenter study of early results with analysis of complications. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:4-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Lee S, Mahar AT, Newton PO. Ender nail fixation of pediatric femur fractures: A biomechanical analysis. J Pediatr Orthop 2001;21:442-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Reeves RB, Ballard RI, Hughes JL. Internal fixation versus traction and casting of adolescent femoral shaft fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 1990;10:592-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Ward WT, Levy J, Kaye A. Compression plating for child and adolescent femur fractures. J Paediatr Orthop 1992;12:626-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Krettek C, Haas N, Walker J, Tscherne H. Treatment of femoral shaft fractures in children by external fixation. Injury 1991;22:263-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Aronson J, Tursky EA. External fixation of femur fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1992;12:157-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Beaty JH, Austin SM, Warner WC, Canale ST, Nichols L. Interlocking intramedullary nailing of femoral-shaft fractures in adolescents: Preliminary results and complications. J Pediatr Orthop 1994;14:178-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Letts M, Jarvis J, Lawton L, Davidson D. Complications of rigid intramedullary rodding of femoral shaft fractures in children. J Trauma 2002;52:504-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Buechsenschuetz KE, Mehlman CT, Shaw KJ, Crawford AH, Immerman EB. Femoral shaft fractures in children: Traction and casting versus elastic stable intramedullary nailing. J Trauma 2002;53:914-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Ligier JN, Metaizeau JP, Prevot J, Lascombes P. Elastic stable intramedullary nailing of femoral shaft fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1988;70:74-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Lascombes P, Haumont T, Journeau P. Use and abuse of flexible intramedullary nailing in children and adolescents. J Pediatr Orthop 2006;26:827-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Hu D, Xu Z, Shi T, Zhong H, Xie Y, Chen J. Elastic stable intramedullary nail fixation versus submuscular plate fixation of pediatric femur shaft fractures in school age patients: A PRISMA-compliant systematic review and meta-analysis. Medicine (Baltimore). 2023 Sep 29;102(39):e35287. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Ribeiro BAG, Kenchian CH, Satake G, Dobashi ET, Galeti AOC. Comparison between flexible nailing and external fixation, methods to stabilize femoral shaft fractures in the immature skeleton: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Acta Ortop Bras. 2024 Oct 7;32(4):e278265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]