Post-operative delirium is common in elderly orthopedic fracture patients, with age, ASA class, general anesthesia, intraoperative hypotension, and blood transfusion as key independent risk factors.

Dr. Devesh Kumar Vyas, Department of Psychiatry, SRVS Government Medical College, Shivpuri, Madhya Pradesh, India. E-mail: deveshvyas88@gmail.com

Background: Post-operative delirium (POD) is a frequent complication among elderly patients undergoing orthopedic fracture surgery, associated with increased morbidity and prolonged hospitalization. Identifying perioperative risk factors is crucial for timely prevention and management.

Materials and Methods: A prospective observational study was conducted on 100 patients aged ≥50 years undergoing surgical fixation of orthopedic fractures. Baseline demographics, comorbidities, American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) class, type of anesthesia, intraoperative hemodynamic parameters, and perioperative factors were recorded. Delirium was assessed daily for 5 post-operative days using the confusion assessment method. Multivariate logistic regression was performed to identify independent risk factors.

Results: POD occurred in 22% of patients. Patients who developed delirium were older (72.4 ± 8.2 vs. 66.1 ± 7.5 years, P = 0.002) and more frequently had ASA class III-IV (54.5% vs. 24.4%, P = 0.01). Delirium was associated with general anesthesia (63.6% vs. 37.2%, P = 0.02), longer surgery duration (128.4 ± 25.2 vs. 108.9 ± 20.5 min, P = 0.001), intraoperative hypotension (50.0% vs. 19.2%, P = 0.005), and perioperative blood transfusion (40.9% vs. 15.4%, P = 0.01). Most cases occurred on the first post-operative day (50%), with a mean duration of 3.2 ± 1.1 days. Independent predictors included age ≥70 years (odds ratio [OR] 2.8), ASA Class III-IV (OR 3.2), general anesthesia (OR 2.6), intraoperative hypotension (OR 3.5), and blood transfusion (OR 2.9).

Conclusion: POD affected one-fifth of orthopedic fracture patients. Advanced age, higher ASA class, general anesthesia, intraoperative hypotension, and blood transfusion were significant independent risk factors. Early identification and targeted perioperative strategies may reduce delirium incidence.

Keywords: Post-operative delirium, orthopedic fractures confusion assessment method, elderly patients

Post-operative delirium (POD) is a prevalent neuropsychiatric complication in elderly patients undergoing orthopedic fracture surgery. Its incidence varies widely, with studies reporting rates ranging from 4% to 53.3%, depending on patient demographics and surgical procedures. This condition is associated with adverse outcomes, including prolonged hospital stays, increased mortality, and long-term cognitive decline [1,2]. Several risk factors have been identified for POD in this patient population. Advanced age is a significant predictor, with older patients exhibiting a higher incidence of delirium. Other notable risk factors include pre-existing cognitive impairment, comorbidities such as cardiovascular disease and diabetes mellitus, and the type of anesthesia used during surgery [3,4]. The pathophysiology of POD remains incompletely understood; however, neuroinflammation and neurotransmitter imbalances are thought to play pivotal roles. In addition, the hypoactive subtype of delirium, which is more prevalent in the elderly, often goes undiagnosed and is associated with poorer outcomes [5,6]. Given the high incidence and serious consequences of POD, early identification of at-risk patients and implementation of preventive strategies are crucial. This study aims to investigate the incidence of POD in elderly orthopedic fracture patients and to identify perioperative risk factors associated with its development.

Study design and setting

This was a prospective observational study conducted in the Department of Orthopedics, in collaboration with the Department of Anesthesiology and Psychiatry, at a tertiary care teaching hospital in India.

Study population

Patients aged ≥ 50 years who were admitted for surgical management of orthopedic fractures (including hip, femur, tibia, and upper limb fractures) were enrolled. Only patients undergoing operative fixation under either general or regional anesthesia were considered.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria

The study included patients aged 50 years and above who were admitted with acute traumatic fractures necessitating surgical intervention. Only those who provided informed written consent were enrolled. Patients with a prior diagnosis of psychiatric disorders or dementia, those presenting with severe head injuries or intracranial pathologies, individuals unwilling to participate, and those requiring intensive care unit admission before surgery were excluded from the study.

Sample size

A minimum of 100 patients were included, calculated at a 95% confidence level with an expected POD incidence of 20% among elderly orthopedic fracture patients, and a margin of error of 7%.

Data collection

Baseline demographic details, comorbidities (hypertension, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, substance use), American Society of Anesthesiologists (ASA) physical status, type of fracture, and type of anesthesia were recorded. Perioperative details, including duration of surgery, intraoperative hemodynamic fluctuations, blood loss, and transfusion requirements, were documented.

Assessment of delirium

POD was assessed daily for the first 5 post-operative days using the confusion assessment method (CAM) [7], a standardized and validated tool. Assessment was performed by trained clinicians not involved in the surgical procedure to minimize bias. Patients were also evaluated using the Mini-Mental State Examination preoperatively to establish baseline cognitive status [8].

Statistical analysis

Data were coded and analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences software version 25.0 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA). Continuous variables were presented as mean ± standard deviation, while categorical variables were expressed as percentages. The Chi-square test and Student’s t-test were used to compare variables. Logistic regression analysis was performed to identify independent risk factors for POD. A P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

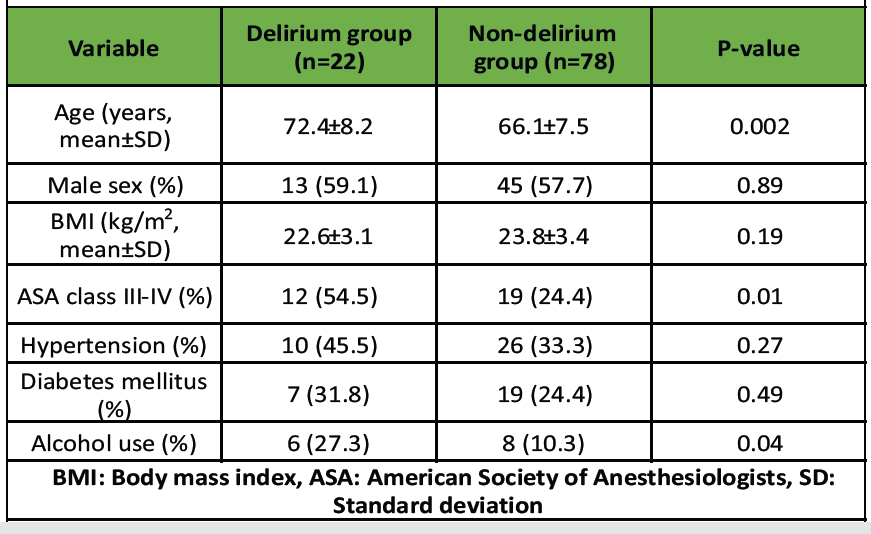

The mean age of patients who developed delirium was significantly higher compared to those without delirium (72.4 ± 8.2 years vs. 66.1 ± 7.5 years; P = 0.002). The proportion of males was comparable between the two groups (59.1% vs. 57.7%; P = 0.89). Although body mass index did not differ significantly (P = 0.19), patients with higher ASA class (III-IV) were more frequently observed in the delirium group (54.5% vs. 24.4%; P = 0.01). Hypertension and diabetes were not significantly associated with delirium, whereas alcohol consumption was more prevalent among patients who developed delirium (27.3% vs. 10.3%; P = 0.04) (Table 1).

Table 1: Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of patients (n=100)

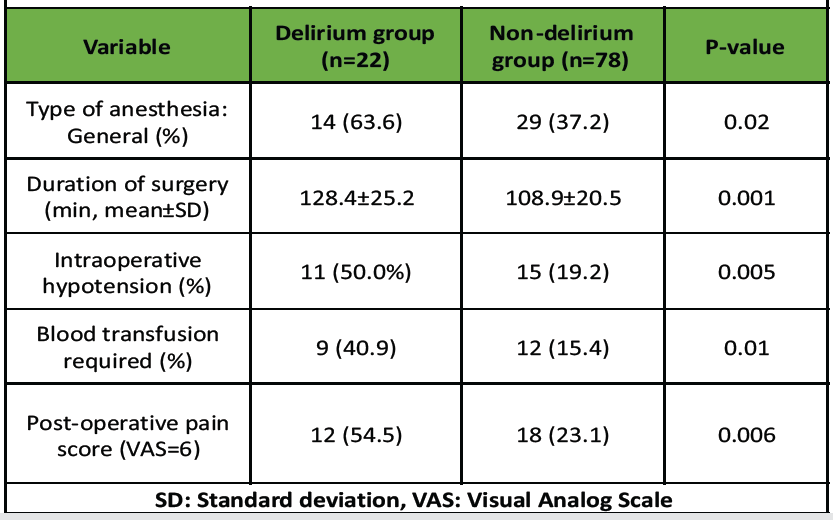

Patients who developed delirium were more likely to have received general anesthesia compared to regional anesthesia (63.6% vs. 37.2%; P = 0.02). The mean duration of surgery was significantly longer in the delirium group (128.4 ± 25.2 min) compared with the non-delirium group (108.9 ± 20.5 min; P=0.001). Intraoperative hypotension was also observed more frequently among delirious patients (50.0% vs. 19.2%; P = 0.005). The requirement for perioperative blood transfusion was significantly higher in the delirium group (40.9% vs. 15.4%; P = 0.01). Post-operative pain scores (visual analog scale ≥ 6) were also significantly elevated in patients with delirium (54.5% vs. 23.1%; P = 0.006) (Table 2).

Table 2: Perioperative variables in patients with and without delirium

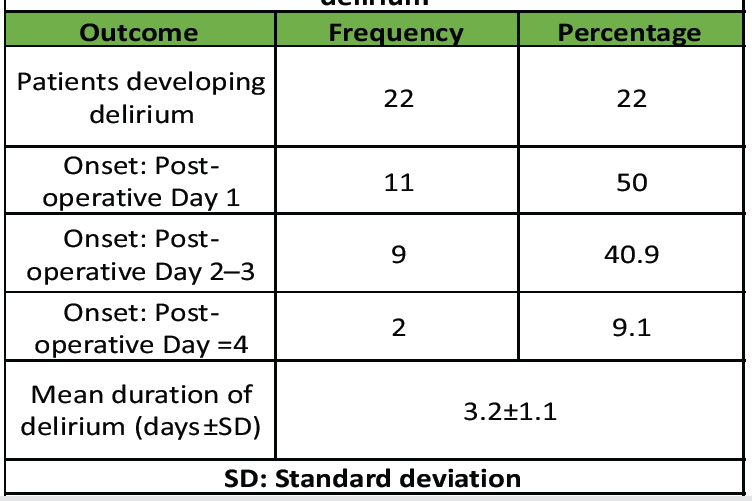

Delirium most commonly presented on the 1st post-operative day (50.0%), followed by the 2nd or 3rd post-operative day (40.9%). Only a small proportion developed delirium after the 4th post-operative day (9.1%). The mean duration of delirium was 3.2 ± 1.1 days (Table 3).

Table 3: Incidence and duration of post -operative delirium

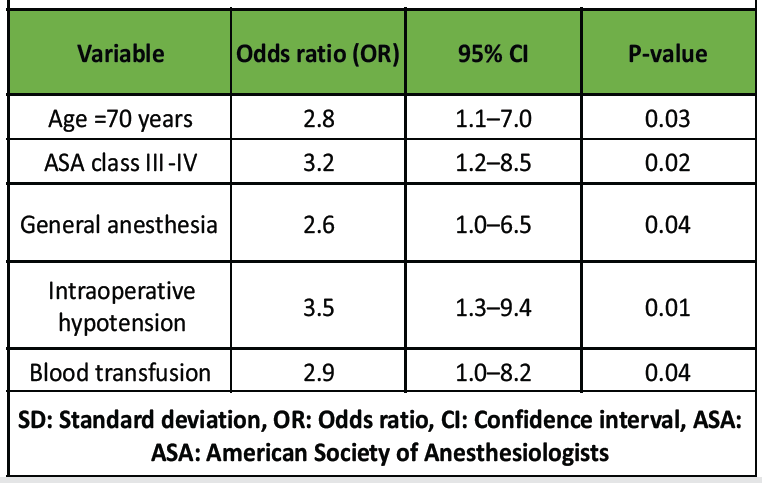

On multivariate logistic regression analysis, age ≥ 70 years (odds ratio [OR] 2.8, 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.1–7.0, P = 0.03), ASA class III-IV (OR 3.2, 95% CI: 1.2–8.5, P = 0.02), general anesthesia (OR 2.6, 95% CI: 1.0–6.5, P = 0.04), intraoperative hypotension (OR 3.5, 95% CI: 1.3–9.4, P = 0.01), and requirement for blood transfusion (OR 2.9, 95% CI: 1.0–8.2, P = 0.04) emerged as independent predictors of POD (Table 4).

Table 4: Logistic regression analysis of independent risk factors for delirium

The incidence of POD in orthopedic fracture patients is a significant concern, with reported rates ranging from 9% to 87%. This variability underscores the complexity of identifying and managing POD in this patient population [9]. Our study identified several key risk factors for POD in elderly orthopedic fracture patients. Advanced age remains one of the most consistent predictors, with each additional decade increasing the risk by approximately 12%. Comorbidities such as diabetes mellitus and pre-operative cognitive dysfunction also significantly elevate the risk. In addition, the type of anesthesia used during surgery plays a crucial role; general anesthesia has been associated with higher incidence rates compared to regional anesthesia [10,11,12]. The underlying mechanisms of POD are multifactorial and not fully understood. Inflammatory responses, particularly elevated C-reactive protein levels, have been implicated in the development of delirium. Furthermore, perioperative blood loss and the duration of surgery contribute to the inflammatory burden, potentially exacerbating the risk [13]. Preventive strategies are paramount in mitigating the incidence of POD. Multicomponent interventions, including pharmacological agents like dexmedetomidine and non-pharmacological approaches such as cognitive stimulation and early mobilization, have shown promise. Moreover, optimizing perioperative care by minimizing blood loss and selecting appropriate anesthesia techniques can further reduce the risk [14]. While our study provides valuable insights, it is not without limitations. First, being a single-center study conducted at a tertiary-care hospital, the findings may not be entirely generalizable to other healthcare settings with differing patient demographics, perioperative protocols, and resource availability. Second, although the sample size (n = 100) was statistically adequate for exploratory analysis, it may have been insufficient to detect associations involving less common or subtle risk factors, thereby limiting the power of multivariate analysis. Third, the follow-up period was limited to the first 5 post-operative days, during which delirium was actively assessed. Consequently, late-onset or persistent cognitive impairments that might have developed beyond this timeframe were not captured. Fourth, patients with pre-existing psychiatric or cognitive disorders were excluded, which, while reducing confounding, also limits the external validity of our results for the broader elderly population where such comorbidities are common. Fifth, despite using a validated tool (CAM), observer-related and assessment bias cannot be completely excluded, as subjective interpretation and interobserver variability might have influenced delirium detection. Sixth, the study did not include biochemical or inflammatory markers such as C-reactive protein, cytokines, or serum electrolytes. Incorporating these parameters could have provided deeper insight into the pathophysiological mechanisms underlying POD. Seventh, medication-related factors (e.g., perioperative use of opioids, benzodiazepines, and anticholinergic agents) were not systematically analyzed, which might have influenced delirium occurrence. Eighth, there was heterogeneity in fracture types and surgical procedures. Variations in operative duration, blood loss, and anesthesia requirements may have contributed to delirium risk, but subgroup analyses were not performed to explore these associations. In addition, potential confounding factors such as nutritional status, perioperative pain control strategies, and sleep disturbances were not assessed, which might have affected delirium outcomes. Finally, the study did not evaluate long-term cognitive and functional outcomes following delirium. Assessing its impact on rehabilitation, quality of life, and mortality would provide valuable prognostic information for future studies. Future research should focus on prospective, multicenter studies employing standardized delirium assessment tools to validate our findings. Investigating the efficacy of specific preventive interventions tailored to high-risk populations, such as those with pre-operative cognitive impairment or significant comorbidities, will be crucial. Furthermore, exploring the role of biomarkers in predicting POD could lead to more targeted and effective prevention strategies.

POD occurred in 22% of orthopedic fracture patients. Advanced age (≥70 years) and ASA class III-IV significantly increased risk. General anesthesia, intraoperative hypotension, and perioperative blood transfusion were independent predictors. Early identification of high-risk patients is critical. Targeted perioperative management may reduce delirium incidence.

Elderly patients undergoing orthopedic fracture surgery should be carefully evaluated for risk factors of POD. Early identification of high-risk individuals allows clinicians to implement targeted perioperative strategies, including selecting appropriate anesthesia, maintaining hemodynamic stability, minimizing blood loss and transfusions, and providing vigilant post-operative monitoring. Such proactive measures can reduce the incidence, duration, and complications of delirium, ultimately improving patient outcomes and shortening hospital stays.

References

- 1. Costa-Martins I, Carreteiro J, Santos A, Costa-Martins M, Artilheiro V, Duque S, et al. Post-operative delirium in older hip fracture patients: A new onset or was it already there? Eur Geriatr Med 2021;12:777-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Penfold RS, Farrow L, Hall AJ, Clement ND, Ward K, Donaldson L, et al. Delirium on presentation with a hip fracture is associated with adverse outcomes: A multicentre observational study of 18,040 patients using national clinical registry data. Bone Joint J 2025;107-B:470-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Chen Y, Liang S, Wu H, Deng S, Wang F, Lunzhu C, et al. Postoperative delirium in geriatric patients with hip fractures. Front Aging Neurosci 2022;14:1068278. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kong D, Luo W, Zhu Z, Sun S, Zhu J. Factors associated with post-operative delirium in hip fracture patients: what should we care. Eur J Med Res 2022;27:40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Zhang DF, Su X, Meng ZT, Cui F, Li HL, Wang DX, et al. Preoperative severe hypoalbuminemia is associated with an increased risk of postoperative delirium in elderly patients: Results of a secondary analysis. J Crit Care 2018;44:45-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Vochteloo AJ, Borger van der Burg BL, Mertens B, Niggebrugge AH, de Vries MR, Tuinebreijer WE, et al. Outcome in hip fracture patients related to anemia at admission and allogeneic blood transfusion: An analysis of 1262 surgically treated patients. BMC Musculoskelet Disord 2011;12:262. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Wei LA, Fearing MA, Sternberg EJ, Inouye SK. The Confusion Assessment Method: A systematic review of current usage. J Am Geriatr Soc 2008;56:823-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Arevalo-Rodriguez I, Smailagic N, Roqué-Figuls M, Ciapponi A, Sanchez-Perez E, Giannakou A, et al. Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) for the early detection of dementia in people with mild cognitive impairment (MCI). Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;7:CD010783. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Fenta E, Teshome D, Kibret S, Hunie M, Tiruneh A, Belete A, et al. Incidence and risk factors of postoperative delirium in elderly surgical patients 2023. Sci Rep 2025;15:1400. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Liu XH, Zhang QF, Liu Y, Lu QW, Wu JH, Gao XH, et al. Risk factors associated with postoperative delirium in elderly patients undergoing hip surgery. Front Psychiatry 2023;14:1288117. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Niu Y, Wang Q, Lu J, He P, Guo HT. Risk factors for postoperative delirium in orthopedic surgery patients: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Med 2025;57:2534520. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Delen LA, Korkmaz Disli Z. A retrospective study of the effects of anesthesia methods on post-operative delirium in geriatric patients having orthopedic surgery: Anesthesia methods on post-operative delirium. J Surg Med 2023;7:324-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. An Z, Xiao L, Chen C, Wu L, Wei H, Zhang X, et al. Analysis of risk factors for postoperative delirium in middle-aged and elderly fracture patients in the perioperative period. Sci Rep 2023;13:13019. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Deblois S, Bergeron N, Vu TT, Paquin-Lanthier G, Nauche B, Pomp A, et al. The prevention and treatment of postoperative delirium in the elderly: A narrative systematic review of reviews. J Patient Saf 2025;21:174-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]