Primary bone lymphoma can closely mimic chronic infection; early biopsy with immunohistochemistry is essential to avoid misdiagnosis and ensure timely treatment.

Dr. Anirudh Dwajan, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bilaspur - 174001, Himachal Pradesh, India. Email: anirudhdwajan@gmail.com

Introduction: Primary bone lymphoma (PBL) is a rare malignancy that often presents with non-specific symptoms and radiological features, making it easily mistaken for infectious or inflammatory conditions. Among its various presentations, tibial involvement mimicking chronic osteomyelitis is particularly uncommon.

Case Report: We report the case of a woman in her 50s with a 6-year history of progressive pain and swelling of the left upper leg. She had previously received multiple empirical antibiotic courses for presumed osteomyelitis over 6 years without sustained benefit. Persistent symptoms and inconclusive radiology prompted further evaluation. Core and open biopsies confirmed diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the proximal tibia. Immunohistochemistry showed positivity for CD45 and CD20, with a high Ki-67 index (60%), establishing the diagnosis. The patient underwent four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy. Given the associated cortical destruction and pathological fracture risk, surgical fixation was deferred. She was managed with a hinged knee brace and structured rehabilitation. At 4 months follow-up, she remained asymptomatic, mobile with a cane, and radiologically stable.

Conclusion: This case underscores the diagnostic challenge of PBL when it masquerades as chronic osteomyelitis. Early tissue biopsy and immunohistochemistry are critical to avoid prolonged misdiagnosis and inappropriate therapy. Clinicians should maintain a high index of suspicion for malignancy in non-resolving bone lesions.

Keywords: Primary bone lymphoma, tibia, diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, chronic osteomyelitis, misdiagnosis.

Primary bone lymphoma (PBL) is a rare malignancy that arises within the bone without initial involvement of visceral organs or widespread lymphadenopathy [1]. It may manifest as multifocal skeletal pathology or as a solitary bone lesion with or without involvement of nearby lymph nodes. Crucially, this category does not include instances with widespread lymph node or visceral dissemination at diagnosis. Although rare, PBL accounts for around 7% of all primary bone tumors, and constitutes less than 2% of all lymphomas in adults [2]. PBL was initially defined by Oberling in 1928. Parker and Jackson identified PBL as a separate entity and described a number of cases under the heading “reticulum cell sarcoma of the bone” [3]. The use of immunohistochemistry has confirmed the lymphoid origin of this entity, most commonly of B-cell lineage. Diffuse large B-cell lymphoma is the most prevalent form of PBL. The histologic type and stage determine the appropriate course of treatment [4]. The prevalence of this disease is marginally larger in men. Skeletal involvement most commonly affects the axial skeleton; however, the femur remains the single most frequently involved bone, seen in up to one-third of cases [5]. The percentage of cases that have bone marrow and lymph node involvement is approximately 35% and 28%, respectively. Diagnosis relies on integrating clinical, radiological, and histopathological data. Immunohistochemical profiling typically demonstrates markers such as CD45, CD20, and CD79a, with variable expression of CD10 and CD75, supporting B-cell lineage [6]. This case is particularly important because bone lymphoma can quietly mimic common conditions such as chronic osteomyelitis, especially in areas where infections are frequently seen. For patients, this often means months or even years of uncertainty, misdiagnosis, and treatments that do not work – delaying the care they truly need. Our case reminds clinicians to keep a broad differential when faced with persistent or unusual bone symptoms, and to consider early tissue biopsy and immunohistochemistry as essential tools in uncovering the correct diagnosis.

A woman in her 50s presented to our outpatient department with a 6-year history of dull, non-radiating pain and gradually progressive swelling over the left upper leg. The pain, which had an insidious onset, worsened at night and with weight bearing, significantly affecting her mobility. She reported no systemic symptoms such as fever or weight loss. She recalled sustaining a direct blow to the same leg following a slip and fall several years ago, for which an above-knee plaster cast was applied at a nearby facility for 1 month. There was no relevant family or social history, and she had no known comorbidities. Over the years, she was repeatedly managed as a case of chronic osteomyelitis and received multiple courses of antibiotics, but symptoms persisted with only transient relief. On clinical examination, diffuse swelling was noted over the proximal third of the left leg, measuring approximately 25 cm in length from 3 cm below the knee joint line. The overlying skin was erythematous and warm to the touch. No scar, sinus, or discharge was present (Fig. 1). Palpation revealed localized tenderness and warmth, with no crepitus or abnormal mobility. The knee joint had a full range of motion. Distal neurovascular examination was normal.

Figure 1: Pre-operative clinical photographs of the left proximal tibia showing localized swelling and fullness around the anteromedial aspect of the upper leg. The overlying skin appears intact with no ulceration, discoloration, or sinus formation. Mild tenderness and warmth were noted on examination.

Based on the chronicity and local signs of inflammation, a provisional diagnosis of osteomyelitis was considered, and empirical intravenous antibiotics were initiated while further investigations were pursued.

Investigations

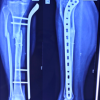

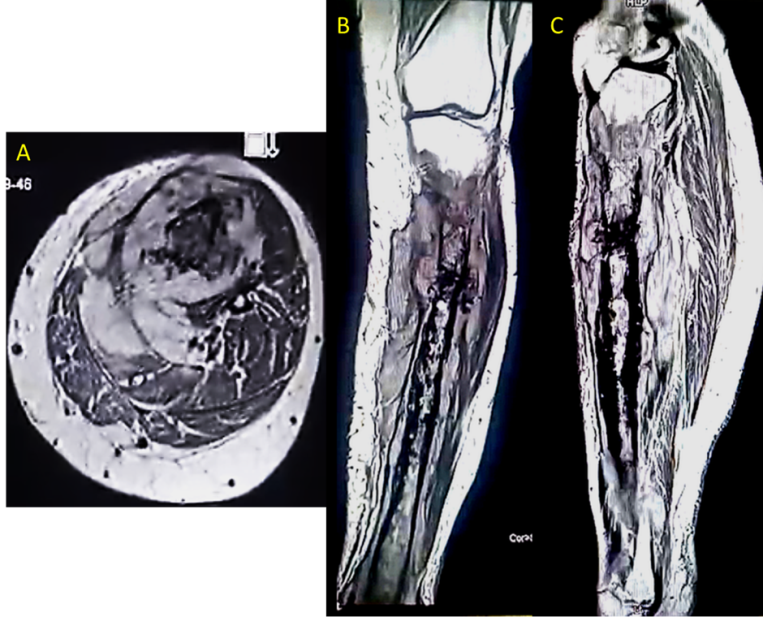

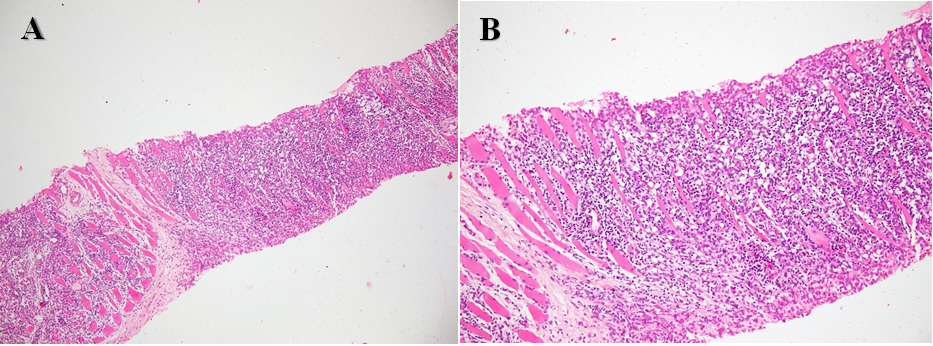

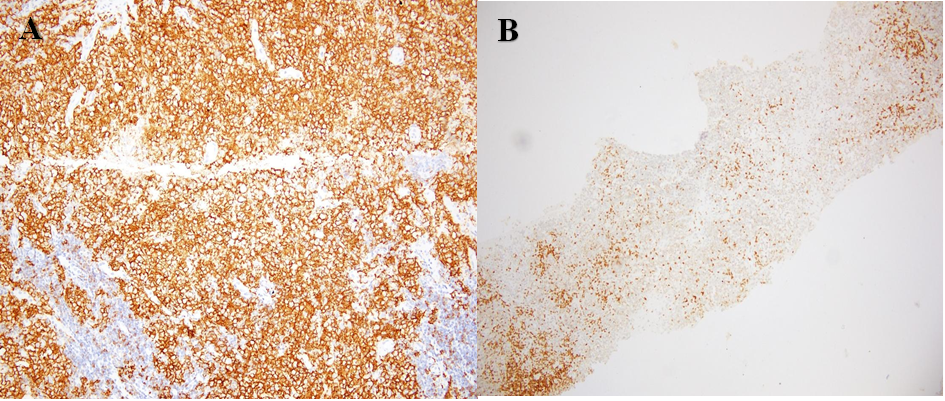

Baseline blood investigations revealed hemoglobin 12 g/dL, leukocyte count 5,000/mm3, platelets 210,000/mm3, erythrocyte sedimentation rate 30 mm/h, and C-reactive protein 5.8 mg/L. Radiographs of the left tibia showed a mixed lytic–sclerotic lesion with cortical breach and periosteal reaction (Fig. 2). Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated an ill-defined metaphyseal lesion with marrow replacement, cortical destruction, soft-tissue extension, and pathological fracture (Fig. 3). Core needle biopsy suggested a hematolymphoid malignancy, confirmed by open biopsy showing diffuse large atypical lymphoid cells (Fig. 4). Immunohistochemistry revealed diffuse CD45 and CD20 positivity, scattered CD3 positivity, and high Ki-67 (~60%) with cytokeratin negativity (Fig. 5). Positron emission tomography-computed tomography (PET-CT) revealed an avid mass in the proximal tibia with metabolically active regional nodes. Cultures were sterile.

Figure 2: Anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left proximal tibia at presentation, demonstrating a lytic, expansile lesion with cortical thinning and breach along the medial cortex, associated with periosteal reaction and surrounding soft-tissue shadow. Findings are consistent with an aggressive destructive process involving the metaphyseal region.

Figure 3: Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging of the left proximal tibia – (a) axial, (b) coronal, and (c) sagittal T2-weighted images – demonstrating a heterogeneous hyperintense marrow lesion with cortical breach and soft-tissue extension along the anteromedial aspect. The lesion involves the metaphyseal region and shows surrounding marrow edema and periosteal reaction, features suggestive of an aggressive infiltrative process.

Figure 4: (a) Photomicrograph of the biopsy specimen showing a core infiltrated by sheets of atypical lymphoid cells with scant cytoplasm, irregular nuclei and coarse chromatin (H&E, ×200), consistent with a high-grade non-Hodgkin lymphoma. (b) High-power photomicrograph demonstrating infiltration of atypical lymphoid cells between skeletal muscle fibres with hyperchromatic nuclei, scant cytoplasm and effacement of normal muscle architecture (H&E, ×400).

Figure 5: (a) Immunohistochemistry showing diffuse membranous CD20 positivity in tumour cells, confirming B-cell lineage; background small lymphocytes are also noted (IHC, ×200). (b) Immunohistochemistry showing scattered CD3-positive background T-lymphocytes within the tumour, highlighting the reactive T-cell population (IHC, ×200). Inset: Ki-67 shows a high proliferative index with labelling of approximately 60% of tumour cells.

Treatment

Once the diagnosis of extranodal B-cell non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma involving the left proximal tibia was confirmed–along with regional lymph node involvement–the disease was classified as Ann Arbor Stage IIE. The interval from presentation to histological confirmation was approximately 3 weeks, and chemotherapy was initiated within 1 week of diagnosis. The patient was started on standard R-CHOP chemotherapy (rituximab, cyclophosphamide, doxorubicin, vincristine, and prednisolone), administered every 4 weeks. She has completed four cycles of chemotherapy over the past 4 months and has tolerated treatment well without major adverse effects. Clinically, she reports marked improvement in pain and reduction in swelling, with progressive recovery of mobility. Follow-up radiographs obtained after 4 months demonstrate interval sclerosis and partial cortical remodeling of the previously lytic proximal tibial lesion, with no new cortical destruction or soft-tissue extension, indicating a favorable response to treatment (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: Follow-up anteroposterior (a) and lateral (b) radiographs of the left proximal tibia obtained after four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy, showing diffuse homogeneous sclerosis and partial cortical remodeling at the site of the previous lytic lesion. No new cortical destruction or soft-tissue extension is seen, indicating a favourable therapeutic response and interval bone healing.

Given the persistent cortical irregularity and risk of fracture, surgical fixation has been deferred. The patient continues on protected weight-bearing and remains under close orthopedic and oncologic supervision.

Outcome

After four cycles of R-CHOP chemotherapy over 4 months, the patient showed marked clinical improvement with resolution of pain and swelling. She is now ambulant with a cane and performing daily activities independently. Follow-up radiographs show early sclerosis and bone healing at the previous lytic site, with no new cortical destruction or progression. She continues physiotherapy and oncology follow-up, with surgical reconstruction to be considered after completion of chemotherapy, based on bone remodeling.

Even though PBL is uncommon, it is a clinically relevant condition that is frequently misunderstood, especially when it presents with vague symptoms and signs. There have been several reports of PBL presenting such as chronic or subacute osteomyelitis, which often leads to it being mistaken for an infection and treated incorrectly [7,8,9,10]. The tibia, though less commonly involved than the femur or pelvis, remains a known site of presentation. In our case, the patient had a 6-year history of progressive leg pain and swelling, initially attributed to chronic osteomyelitis. This diagnostic confusion is not uncommon. PBL often mimics chronic infectious or inflammatory bone conditions, leading to empirical antibiotic use and delays in initiating definitive treatment [9,10]. Radiologically, lytic or sclerotic lesions with soft-tissue involvement and periosteal reaction may resemble chronic infection or even metastatic disease. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) plays a critical role in evaluating bone lesions, yet its diagnostic utility in PBL remains challenging due to considerable variability in radiologic appearance. Previous studies have described certain imaging clues that might suggest PBL. Stiglbauer et al. [11] observed that PBL often shows some typical patterns – like appearing hypointense on T2-weighted MRI scans, being located near the ends of long bones, and sometimes involving the nearby joints. In a retrospective series by Heyning et al., most patients exhibited soft-tissue masses that were isointense on T1-weighted imaging and hyperintense on T2-weighted sequences, aligning more with typical neoplastic patterns. Interestingly, about 31% of patients in their cohort had only subtle cortical signal changes without a significant soft-tissue component–—features that could easily be mistaken for benign or inflammatory process [12]. Mulligan et al. [13] and Krishnan et al. [14] evaluated patterns of cortical bone destruction as a means of distinguishing PBL from other diagnoses. Krishnan et al. proposed that in patients over the age of 30 years, the presence of a meta-diaphyseal lesion accompanied by marrow signal alterations, cortical involvement, and an associated soft-tissue mass was highly indicative of PBL. In our patient, the MRI findings included marrow signal changes, cortical destruction, and soft-tissue extension – features that closely resembled those seen in the majority of cases reported by Heyning et al. Suspicion of the tibiotalar joint was also noted, which was in accordance with the findings of Stiglbauer et al. However, the lesion in our case was hyperintense on T-2 MRI in contrast. Taken together, these findings emphasize that while MRI remains indispensable, it cannot reliably distinguish PBL from other pathologies in isolation. The lack of uniform imaging features reinforces the need for timely histological evaluation, particularly when standard treatments fail or clinical suspicion persists. PET-CT has shown significantly higher effectiveness in staging extranodal lymphomas, with sensitivity, specificity, and accuracy rates reaching 97%, 100%, and 98%, respectively. In contrast, conventional CT imaging demonstrates lower rates of 87%, 85%, and 84% for the same parameters [15]. Definitive diagnosis requires tissue biopsy and immunohistochemistry. In our case, the tumor cells expressed diffuse membranous positivity for CD20 and expression of CD45 in tumor cells, with a high proliferative index (Ki-67 ≈ 60%). Scattered CD3-positive lymphocytes represented background T-cells; cytokeratin was negative. This immunophenotype is typical of diffuse large B-cell lymphoma (DLBCL), which is the most common histological subtype of PBL. The high Ki-67 index (60%) reflected a high proliferative rate, correlating with the aggressive biology of DLBCL. Staging is performed using the Ann Arbor system, with stage I-II disease (bone ± regional lymph node involvement) associated with favorable outcomes. Our patient was classified as stage II E. Treatment of PBL typically involves immunochemotherapy with the R-CHOP regimen. This combination has dramatically improved outcomes, with 5-year survival rates exceeding 80–90% in localized disease [16]. While radiotherapy has historically been used for local control, recent evidence supports chemotherapy alone in many early-stage cases, especially when radiological response is favorable [1 7]. In our patient, functional rehabilitation played a crucial role in recovery. Due to the extent of cortical destruction, internal fixation was deferred, and a structured physiotherapy regimen was initiated. She made gradual progress and regained ambulatory function with assistive devices. This case highlights the importance of considering PBL in the differential diagnosis of chronic bone pain and swelling, especially when imaging and laboratory findings are inconclusive or unresponsive to conventional treatments.

This case highlights the importance of considering PBL in the differential diagnosis of chronic bone pain and swelling, especially when imaging and laboratory findings are inconclusive or unresponsive to conventional treatments.

PBL may mimic chronic osteomyelitis and lead to prolonged misdiagnosis. A biopsy with immunohistochemistry is essential for accurate diagnosis.

References

- 1. Unni KK, Fletcher CD, Mertens F. Pathology and genetics of tumors of soft tissue and bone. WHO classification of tumors. In: Malignant lymphoma. 3rd ed., Vol. 5 and 23. Lyon: IARC Press, World Health Organization; 2002. p. 13-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Limb D, Dreghorn C, Murphy JK, Mannion R. Primary lymphoma of bone. Int Orthop 1994;18:180-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Ibran M, Ahmad S, Aggarwal P, Ashfaque MU, Anwer A. Primary bone lymphoma of proximal tibia presenting with pathological fracture: A case report. J Bone Joint Dis 2023;38:266-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Bruno Ventre M, Ferreri AJ, Gospodarowicz M, Govi S, Messina C, Porter D, et al. Clinical features, management, and prognosis of an international series of 161 patients with limited-stage diffuse large B-cell lymphoma of the bone (the IELSG-14 study). Oncologist 2014;19:291-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Messina C, Christie D, Zucca E, Gospodarowicz M, Ferreri AJ. Primary and secondary bone lymphomas. Cancer Treat Rev 2015;41:235-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Huebner-Chan D, Fernandes B, Yang G, Lim MS. An immunophenotypic and molecular study of primary large B-cell lymphoma of bone. Mod Pathol 2001;14:1000-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Altshuler E, Worhacz K. Report of missed non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma presenting as pathological tibial fracture. Cureus 2021;13:e18914. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Bralić M, Stemberga V, Cuculić D, Coklo M, Bulić O, Grgurević E, et al. Primary non-Hodgkin’s lymphoma of the humerus presenting as osteomyelitis. Coll Antropol 2008;32 Suppl 2:229-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Jayaprakasan P, Warrier A. Primary bone lymphoma of the shaft of the tibia, mimicking subacute osteomyelitis. Cureus 2023;15:e38070. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Fudala ML, Karam I, Thida AM, Khan I, Hamadi R, Macapagal-Brown N, et al. Rare case of primary bone lymphoma. Cureus 2025;17:e84415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Stiglbauer R, Augustin I, Kramer J, Schurawitzki H, Imhof H, Radaszkiewicz T. MRI in the diagnosis of primary lymphoma of bone: Correlation with histopathology. J Comput Assist Tomogr 1992;16:248-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Heyning FH, Kroon HM, Hogendoorn PC, Taminiau AH, Van Der Woude HJ. MR imaging characteristics in primary lymphoma of bone with emphasis on non-aggressive appearance. Skeletal Radiol 2007;36:937-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Mulligan ME, McRae GA, Murphey MD. Imaging features of primary lymphoma of bone. AJR Am J Roentgenol 1999;173:1691-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Krishnan A, Shirkhoda A, Tehranzadeh J, Armin AR, Irwin R, Les K. Primary bone lymphoma: Radiographic-MR imaging correlation. Radiographics 2003;23:1371-83; discussion 1384-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Paes FM, Kalkanis DG, Sideras PA, Serafini AN. FDG PET/CT of extranodal involvement in non-Hodgkin lymphoma and Hodgkin disease. Radiographics 2010;30:269-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Bindal P, Desai A, Delasos L, Mulay S, Vredenburgh J. Primary bone lymphoma: A case series and review of literature. Case Rep Hematol 2020;2020:4254803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Scoccianti G, Rigacci L, Puccini B, Campanacci DA, Simontacchi G, Bosi A, et al. Primary lymphoma of bone: Outcome and role of surgery. Int Orthop 2013;37:2437-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]