The prone reduction technique offers a simple, effective, and low-resource method for achieving excellent anatomical and functional outcomes in paediatric Gartland type II supracondylar humerus fractures, even in outpatient settings.

Dr. Vishwas Kadambila, Department of Orthopaedics, Kanachur Institute of Medical Sciences, Mangaluru, Karnataka, India. E-mail: vishwask77@gmail.com

Introduction: In and around elbow in pediatric age group, fractures in the supracondylar region of humerus are the most common. Displaced fractures are treated operatively and undisplaced fractures conservatively. Treatment of minimally or partially displaced supracondylar fractures depends on the adequacy and quality of reduction in the outpatient setting. We observed that there was a scope for a newer technique of reduction in these fractures. This study analyzes the functional outcome after prone method of reduction in extension type 2 Gartland pediatric supracondylar fractures of humerus.

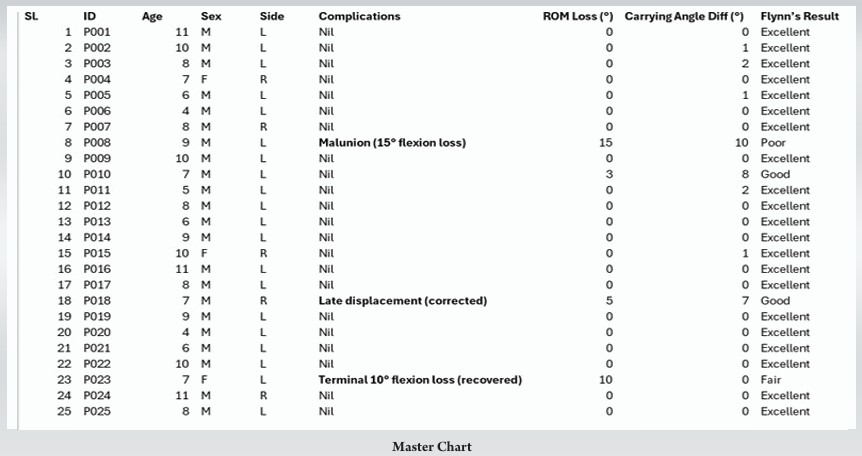

Materials and Methods: This study was of prospective design from January 2019 to January 2020. Twenty-five patients of type-II supracondylar humerus fracture were included. After consent, under local hematoma block, in prone position, reduction technique was performed. Patients were evaluated at 1, 3, 6, 12, and 24 weeks. Criteria of Flynn were used to gauge the clinical outcome.

Results: Study included 25 patients, 22 being male and three females. Twenty patients had fracture in the left side and five had in right. Age of patients ranged from 4 to 11 years, with 8.1 being the mean age. Criteria of Flynn were used to assess outcome. Excellent outcome was obtained in 21 (84%) and good outcome in 2 (8%) patients. One (4%) patient had fair and 1 (4%) had poor outcome.

Conclusion: Prone method of reduction provides us with a new option of safe and effective method of treating pediatric Gartland type 2 humerus supracondylar fractures, which can be performed even in a low-resource setting. This technique permits excellent fracture reduction and, thereby, can avoid operative intervention.

Keywords: Supracondylar humerus, prone reduction, practical technique.

Supracondylar humerus fracture refers to fracture of distal humerus that involves the thin segment through coronoid or the olecranon fossae, or just proximal to it or through distal metaphysis of humerus. In the pediatric age group, fracture that most commonly requires surgical intervention is the fracture of supracondylar humerus which also happens to be the most typical elbow fracture in this age group [1]. These fractures peak around the age group of 4 to 6 years with mean age of presentation being 5.5 years [2]. Fall onto an extended limb leads to these fractures and depending on where the distal fragment shifts, the injury is classified as either an extension or flexion type [3,4]. Extension type is the usual presentation 98% of the time, with flexion being the rest 2% 2. Gartland differentiated the Extension type fractures into further three types [5]. Non-displaced fractures were named type 1, fractures that maintained posterior hinge of periosteum were named type 2, and completely, displaced fractures were grouped as type 3 [2]. Further subdivisions have been made later by other authors for type 2, but there is little benefit in dividing type 2 fractures into subtypes [1]. Although there have been more than 500 peer reviewed articles on supracondylar fractures in the last decade, there remains poor consensus on many areas of treatment. An 88-question survey of 35 pediatric orthopedic surgeons on these fractures found consensus on only 27% of the questions [6]. The management is dictated by the fracture pattern and the degree of fracture fragment displacement [2]. Undisplaced type 1 fractures are conservatively treated with an above elbow cast and displaced type 3 fractures are managed operatively with closed reduction of the fracture and fixation with Kirschner wires. Treatment of minimally or partially displaced type 2 supracondylar fractures is controversial [2] and banks on the adequacy of reduction achieved in the outpatient setting, as anatomically aligned fractures can go ahead with casting while malreduced ones would require pinning. Pediatric supracondylar fracture of humerus can instill a sense of urgency in the surgeon due to the crippling sequelae associated with it. Hence, the proper management of injury around the elbow is important and great care is required to secure a good outcome and to avoid complications such as Ischemic contracture of Volkmann, heterotopic ossification, injury to neurovascular structures, deformities such as cubitus varus or valgus, and stiffness of elbow or loss of function of elbow [7]. In general, reduction is tried with patient in supine position using traction countertraction method [8] as described by Sir Charnley. Although mediolateral corrections are well achieved, we have observed that by this method in quite a few cases, olecranon posterior tilt is not corrected and as a result patient has to undergo operative intervention and expose himself/herself to the complications associated with it. Hence, inspired by Parvin’s method of reduction of elbow dislocation [9], we came up with the prone method of reduction. Our study aims to interpret the functional outcome after prone method of reduction in pediatric Gartland type 2 extension supracondylar fractures of humerus.

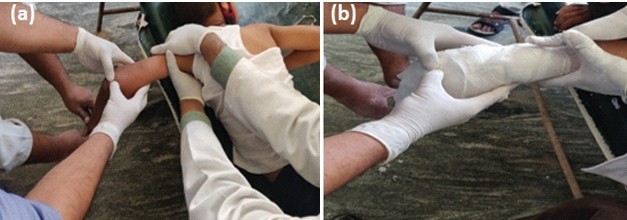

This was a study with prospective design in a referral hospital from January 2019 to January 2020 in a tertiary care hospital after obtaining Institutional Ethical Committee clearance (EC REG: ECR/134/Inst/KA/2013/RR-16.) Twenty-five patients within age group of 4–12 years of type 2 Gartland fracture presenting within 7 days of injury were included [Master Chart].  Gartland type 1 and 3 fractures, open fractures, comminuted fractures, other bone fracture in ipsilateral limb, pathological fracture, and fracture with neurovascular compromise were excluded. The children were examined in the outpatient setting. Injury mechanism and the presenting complaints were elicited both from the child and parents. Routine general examination was done followed by local examination of affected elbow. Neurovascular status of limb ascertained. Required X-rays including anteroposterior, true lateral views were captured to appreciate the type of fracture. Necessary consent for the procedure obtained and reduction performed. Reduction procedure-child is made to lie prone comfortably on the bed with the forearm hanging by the side of the bed for 5 min so that child is relaxed and cooperative to the procedure and also to allow gravity to play its part (Fig. 1).

Gartland type 1 and 3 fractures, open fractures, comminuted fractures, other bone fracture in ipsilateral limb, pathological fracture, and fracture with neurovascular compromise were excluded. The children were examined in the outpatient setting. Injury mechanism and the presenting complaints were elicited both from the child and parents. Routine general examination was done followed by local examination of affected elbow. Neurovascular status of limb ascertained. Required X-rays including anteroposterior, true lateral views were captured to appreciate the type of fracture. Necessary consent for the procedure obtained and reduction performed. Reduction procedure-child is made to lie prone comfortably on the bed with the forearm hanging by the side of the bed for 5 min so that child is relaxed and cooperative to the procedure and also to allow gravity to play its part (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Patient position.

After local hematoma block, gentle traction applied at the forearm by the surgeon and countertraction applied at axilla by an assistant (Fig. 2a). Thumb is centered on the olecranon and other fingers are wrapped around proximal fragment while giving traction in the other hand and the elbow is slowly flexed (Fig. 2b).

Figure 2: Traction, (a) Traction at forearm and countertraction at axilla, (b) Elbow slowly flexed with thumb centered on olecranon and other fingers encircling proximal fragment.

Forearm is kept in supination for posterolateral displacements and in pronation for posteromedial displacements, if any. Now, the second assistant checks adequacy of radial pulse and takes over in providing traction. The surgeon places both thumbs on olecranon while the other fingers encircle the proximal fragment (Fig. 3a). Cotton is applied while keeping thumb on the olecranon and then an above elbow Plaster of Paris slab is applied (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: Reduction and splint/slab application, (a) Second assistant takes over to provide traction and the surgeon now reduces the fracture with both thumbs on olecranon and other fingers encircling proximal fragment to reduce the fracture, (b) Above elbow splint/slab applied.

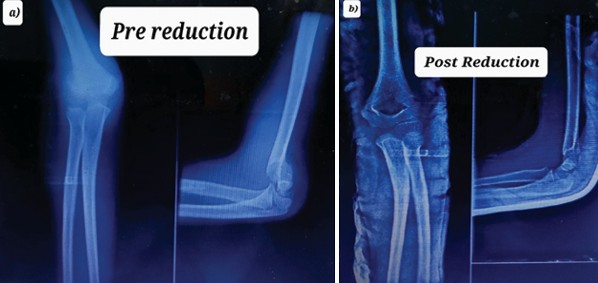

Window is made volarly at the wrist area (Fig. 4a) and integrity of radial pulse confirmed (Fig. 4b). Arm sling applied (Fig. 4c). Child is sent to X-ray (Fig. 5). Post confirmation of reduction in X-ray, patient was prescribed analgesics and advised limb elevation and active movement of fingers in home.

Figure 4: Checking adequacy of radial pulse, (a) Window done, (b) Pulse checked, (c) Final picture

Figure 5: X-rays (a) Pre reduction, (b) Post reduction.

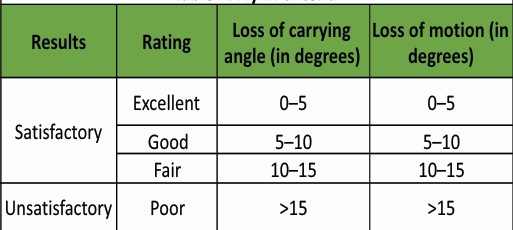

At the end of 1 week, after confirming maintenance of reduction with X-ray, conversion to above elbow cast was done. At the end of week 3 or when the fracture clinically united, cast was removed and joint mobilized. Further follow-up was done at 6, 12, and 24 weeks. Flynn criteria (Table 1) were used to measure functional outcome and Baumann angle for radiological outcome. The Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 27 software and Microsoft office were utilized to analyze data.

Table 1: Flynn criteria

This study comprised a total of 25 extension type 2 Gartland patients. All patients completed their follow-up. Twenty-two (88%) patients were male and rest 3(12%) female. Twenty patients (80%) had fracture in the left side and 5 (20%) had in right. Age of patients ranged from 4 to 11 years, with 8.1 being the mean age. Among these, 7 (28%) were of 4–6 year age group, 11(44%) of 7–9 year age group, and 8 (32%) of 10–11 year age group. All the fractures could be reduced satisfactorily in a single attempt in the outpatient setting with minimal gentle traction. All fractures achieved union in our study. There were no major complications such as compartment syndrome, cubitus varus, nerve palsies, and no cases requiring surgical intervention in our study. Complication of mild extension malunion with loss of terminal 15° of flexion with corresponding hyperextension was found in one patient, without any functional disability. Late displacement at 1 week was seen in one patient who could be reduced with adequate traction by the same technique. One patient had terminal 10° flexion loss which was regained following activities of daily living. Criteria of Flynn were used to assess outcome. Satisfactory result was observed in 24 (96%) cases with excellent outcome obtained in 21 (84%) and good outcome in 2 (8%) patients. One (4%) patient had fair and 1 (4%) had poor outcome.

The most usual fracture requiring surgical intervention in children is a fracture of the supracondylar region of the humerus. While many studies have been done in the past formulating the treatment strategies, not many focused on reduction techniques. We were of the opinion that reduction techniques of type 2 humerus fractures of supracondylar region could be explored and improved on and help prevent unavoidable surgeries. Hence, our study could be seen as a pioneer study in that aspect. In spite of being the most common pediatric elbow fracture, there is shortage of high quality scientific information on management of these fractures [10]. Level 3 evidence, or occasionally only level 4 and 5 data, is currently available to suggest treatment choices for type 2 fractures. The majority of earlier research have amalgamated Gartland types 2 and 3 fractures, making it challenging to assess type 2 fractures independently. That’s why, in our research, we have restricted study group to include type 2 Gartland fractures exclusively. Fractures of the supracondylar humerus almost exclusively occur in the developing skeleton, frequently in the first decade. Weak skeletal architecture and other anatomical variables may contribute to this predisposition. Remodeling is active around elbow at the age of peak incidence for supracondylar fractures, with reduced anteroposterior and lateral diameter leading to a wafer-thin bone with hourglass shape as seen laterally and not as of a cylinder like in a mature skeleton. The child’s metaphysis reaches barely distally to the two fossae where this fracture occurs. On elbow extension, the olecranon engages on its fossa which behaves like a fulcrum, and the distal end of the humerus receives tensile force from the anterior side of the capsule. These results, in pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures, were that the periosteum is torn anteriorly and called as extension type. The fracture is stabilized by the intact posterior periosteal hinge, which aids in reduction [11]. In a Gartland type 2 fracture, cortex is likely to be intact posteriorly, but hinged. On a true lateral X-ray image of the elbow, the humeral anterior line does not cross the center of the capitulum. The anterior humeral line does not pass through the middle part of the capitulum on a true lateral radiograph of the elbow. Since the posterior hinge is intact; generally, an anteroposterior radiograph does not reveal any rotational distortion. Any rotational distortion indicated on an anteroposterior X-ray would classify the fracture as type 3 according to conventional classification [1]. Supracondylar fracture demands anatomical reduction. Accepting a subpar reduction in a misplaced position produces poor consequences, such as restriction to movement in the joint, varus, and valgus abnormalities. Therefore, the most crucial element in the treatment of these fractures is correct anatomic reduction. Typically, closed reduction followed by a long arm splint, skeletal traction, closed reduction pinning, and open fixation with Kirschner wires is the techniques of modalities used for treatment [12]. Silva et al., in their study, suggested that successful non-operative treatment was more likely to be achieved in fractures with extension deformity without any rotational or coronal malalignment [13]. The surgical process requires the use of general anesthesia, an anesthesiologist, and a fully operational and staffed operating room. These resources come with high medical expenditures, and although the dangers of general anesthesia in children are small, they should not be understated. Fitzgibbons et al., postulated possible factors contributing to failure in non-operative management, those being significant deformity as determined by magnitude of extension of the distal fragment, not able to achieve adequate elbow flexion within the cast, and/or usage padding that is more than required in the cast technique [14]. They believed that a cast with excessive extension or with a lot of padding would insufficiently immobilize the fracture. They were of opinion that primary close reduction and casting should be used to treat all type 2 fractures, with the exception of considerably swollen elbows or fractures with significantly extended distal fragment. In addition, they stated that although closed reduction and casting is a suitable choice for treating type 2 fractures, some fractures will eventually lose their alignment and will need delayed pinning. Hadlow et al., refuted the protocols that supported to pin all type 2 fractures, demonstrating that 77% of patients would have endured an unnecessary surgery [15]. Many articles state that close reduction and casting is still appropriate in type 2 fractures. For instance, Parikh et al. found that in managing type 2 fractures with closed cast at 90–100° of elbow flexion, 72% of patients maintained reduction. In addition, they demonstrated that despite the up to 3-week delay, neither the difficulty of the surgical procedure nor the result was impaired in unsuccessful instances changed to closed pinning [16]. Therefore, non-operative treatment is an alternative that may help reduce the cost and risk of unneeded surgery. Roberts et al., opined that although percutaneous pinning appears to be a minimally invasive treatment, it still has the usual hazards associated with surgery, including the possibility of infection at the pin site and iatrogenic nerve injury [17]. Closed casting is a treatment option avoids these complications. In the study, we conducted that 32% of the patients belonged to 7–9 years age bracket with 8.1 years as mean age. Our results compared to other studies – 7.4 (Edward et al.) [18], 4.5 (Skaggs et al.) [19], 4.8 (Silva et al) [13], 4.1 (Roberts et al.) [17], 4.4 (Parikh et al.) [16], and 5.9 (Fitzgibbons et al.) [14]. In our study, left to right side ratio was 4:1. Non-dominant was involved more, probably as a result of its frequent use as a defensive reaction to safeguard the body when falling. Our results compared to other studies – 1.8:1 (Parikh et al) [16], 1.2:1 (Skaggs et al.) [19], and 1.4:1 (Camus et al.) [20]. The differences in side and age with other studies could be attributed to the demographic variations in the fracture. About 88% of the patients in the current study were men. Males tend to be more active than females, which may contribute to their higher rate of fractures. The majority of studies have revealed a masculine predominance 13–15. The measured Baumann angle in our study was similar to that of the normal opposite limb. We had 96% of satisfactory (Excellent +good + fair) result in our study. We could not find any other similar research using prone technique of reduction to compare, for type 2 fractures. The results obtained in studies that employed regular supine method of reduction were – 72% (Parikh et al. [15]) and 80% (Fitzgibbons et al. [16]). This may indicate that our method has better chances of reducing the fracture. Complication of malunion with loss of 15° of terminal flexion with corresponding hyperextension was found in one patient. Physical therapy was advised, but they were not willing for the same as there was no functional disability. Malunion could be attributed to improper technique with thumb of surgeon not staying at olecranon or inadequate traction while reduction and irregular follow-up by the said patient. And as opined by Camus et al., remodeling could restore the humerocapitellar angle’s anterior-posterior alignment up to some extent [20]. One patient presented with late displacement at 1 week. It could be reduced with adequate traction by the same technique which was maintained as seen in further follow-ups. One patient had loss of elbow flexion of 9°. In this instance, we believed that the child’s mobility would return to normal with regular everyday activities. New information about the outcome of nonoperatively treated type 2 supracondylar fractures is provided by our study. With the exception of one subject, everyone else maintained proper alignment without losing any reduction. These results mirror other studies [14,16] that also reported a good outcome for non-operative treatment. In our research, no instances of compartment syndrome were noted. In addition, there was no conversion to surgical treatment required. Therefore, our research implies that the likely result of the prone method of reduction is a full range of motion with a satisfactory functional outcome. Ours is a prospective study with a small size without any comparative group. Further randomized control trials with bigger study group and a comparative group would shed more light on better management of these fractures.

Prone method of reduction provides us with a new option of safe and effective method of treating pediatric Gartland type 2 humerus fractures of supracondylar area, which can be performed even in a low-resource setting. Distal fragment’s posterior tilt is well corrected and reduced anatomically by this method leading to excellent functional results. This technique permits excellent fracture reduction and, thereby, can avoid operative intervention. Further research involving a bigger size of sample and a comparative group would give us an even better insight.

In pediatric Gartland type 2 supracondylar fractures, the prone reduction technique can be safely performed in an outpatient setting with minimal equipment. It provides stable reduction, excellent functional outcomes, and avoids the risks and costs associated with surgical fixation, making it a valuable option in resource-limited environments.

References

- 1. Skaggs DL, Flynn JM. Supracondylar fractures of the distal humerus. In: Waters PM, Skaggs DL, Flynn JM, editors. Rockwoods and Wilkins Fractures in Children. 9th ed. Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer; 2020. p. 479-527. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Sawyer JR, Spence DD. Fracture and dislocations in children. In: Azar FM, Beaty JH, edsitors. Campbells Operative Orthopaedics. 14th ed. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2021. p. 1502-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Dimeglio A. Growth in pediatric orthopedics. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, editors. Lovell and Winters Paediatric Orthopedics. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2006. p. 35-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Cheng JC, Lam TP, Maffulli N. Epidemiological features of Supracondylar fractures of the humerus in Chinese children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2001;10:63-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Gartland JJ. Management of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Surg Gynecol Obstet 1959;109:145-54. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Iobst CA, Stillwagon M, Ryan D, Shirley E, Frick SL. Assessing quality and safety in pediatric supracondylar humerus fracture care. J Pediatric Orthop 2017;37:e303-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Weiland AJ, Meyer S, Tolo VT, Berg HL, Mueller J. Surgical treatment of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Analysis of fifty-two cases followed for five to fifteen years. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1978;60:657-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Charnley J. The closed treatment of common fractures. In: Supracondylar Fractures of the Humerus in Children. 4th ed., Ch. 7. United Kingdom: Cambridge University Press; 2003. p. 105-15. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Egol KA, Koval KJ, Zuckerman J. Handbook of Fractures. Elbow Dislocation. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Wolters Kluwer; 2020254. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Howard A, Mulpuri K, Abel MF, Braun S, Bueche M, Epps H, et al. The treatment of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:320-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Omid R, Choi PD, Skaggs DL. Supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1121-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Pirone AM, Graham HK, Krajbich JL. Management of displaced extension-type supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1988;70;641-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Silva M, Delfosse EM, Park H, Panchal H, Ebramzadeh E. Is the “appropriate use criteria” for Type II supracondylar humerus fractures really appropriate? J Pediatr Orthop 2019;39:1-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Fitzgibbons PG, Bruce B, Got C, Reinert S, Solga P, Katarincic J, et al. Predictors of failure of nonoperative treatment for type-2 supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2011;31:372-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Hadlow AT, Devane P, Nicol RO. A selective treatment approach to supracondylar fracture of the humerus in children. J Pediatr Orthop 1996;16:104-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Parikh SN, Wall EJ, Foad S, Wiersema B, Nolte B. Displaced Type II extension supracondylar humerus fractures: Do they all need pinning? J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:380-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Roberts L, Strelzow J, Schaeffer EK, Reilly CW, Mulpuri K. Nonoperative treatment of Type IIA supracondylar humerus fractures: Comparing 2 modalities. J Pediatr Orthop 2018;38:521-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Abraham E, Gordon A, Hadi OA. Management of supracondylar fractures of humerus with condylar involvement in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2015;25:709-16. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Skaggs DL, Sankar WN, Albrektson J, Vaishnav S, Choi PD, Kay RM. How safe is the operative treatment of Gartland type 2 supracondylar humerus fractures in children? J Pediatr Orthop 2008;28:139-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Camus T, MacLellan B, Cook PC, Leahey JL, Hyndman JC, El-Hawary R. Extension type II pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures: A radiographic outcomes study of closed reduction and cast immobilization. J Pediatr Orthop 2011;31:366-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]