Vitamin D deficiency in primary knee osteoarthritis is significantly associated with elevated IL-6 levels, suggesting a potential role in modulating inflammatory pathways.

Dr. Madhan Jeyaraman, Department of Orthopaedics, ACS Medical College and Hospital, Dr. MGR Educational and Research Institute, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: madhanjeyaraman@gmail.com

Introduction: Osteoarthritis (OA) of the knee is a prevalent degenerative condition influenced by inflammatory processes. Vitamin D possesses immunomodulatory properties that could potentially impact cytokine expression, notably interleukin (IL)-6 and -10, in osteoarthritic pathology. This study investigates the correlation between serum vitamin D (25-hydroxyvitamin D₃) levels and serum concentrations of pro-inflammatory cytokine IL-6 and anti-inflammatory cytokine IL-10 among patients with primary knee OA.

Material And Methods: This cross-sectional observational study included 80 patients aged above 45 years diagnosed with primary knee OA confirmed radiologically (Kellgren–Lawrence grading). Participants underwent serum analysis for vitamin D₃, IL-6, and IL-10. Clinical severity was assessed through the Visual Analog Scale (VAS) for pain and the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) for functional impairment. Data analysis employed Pearson correlation and analysis of variance.

Results: Mean serum vitamin D₃ was 27.9 ± 12.2 ng/mL. IL-6 showed significant elevation in vitamin D-deficient patients (128.2 ± 142.5 pg/mL) compared to vitamin D-insufficient (49.5 ± 36.2 pg/mL) and sufficient groups (28.7 ± 14.9 pg/mL) (P < 0.001). IL-10 levels did not vary significantly across vitamin D status groups. Pearson’s correlation demonstrated a significant inverse relationship between vitamin D₃ and IL-6 (r = –0.444; P < 0.001), while correlations with IL-10, VAS, and WOMAC scores were non-significant.

Conclusions: A significant inverse association between serum vitamin D₃ levels and IL-6 concentrations highlights a potential role of vitamin D in modulating inflammation in knee OA. However, no correlation was observed between vitamin D status, cytokine levels, and clinical OA severity. Longitudinal research is required to assess the therapeutic implications of vitamin D supplementation on inflammation and OA progression.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, vitamin D, interleukin-6, interleukin-10, inflammation, knee joint.

Osteoarthritis (OA) is one of the most prevalent musculoskeletal disorders, with the knee being a major weight-bearing joint frequently affected by this condition [1]. The American College of Rheumatology classifies knee OA into two categories: Primary and secondary [2]. Primary OA arises without a clearly defined cause, whereas secondary OA is attributed to identifiable risk factors such as joint trauma, skeletal deformities, obesity, metabolic bone diseases including avascular necrosis and osteoporosis, autoimmune disorders like rheumatoid arthritis (RA), endocrine conditions, and calcium deposition disease. These factors help delineate secondary OA from primary, which lacks a clear etiopathogenesis. A multicentric study conducted across five Indian cities – Pune, Agra, Bangalore, Kolkata, and Dehradun – reported a marked variation in the prevalence of primary knee OA: 33.2% in large cities, 19.3% in smaller urban areas, 18.3% in towns, and 29.2% in rural settings [3]. Despite the high burden of disease, the exact pathophysiological mechanisms underlying OA remain only partially understood. Inflammatory processes have been increasingly implicated in the early pathogenesis of OA, though whether inflammation is a primary trigger or a secondary response remains debated [4,5]. Multiple studies have demonstrated the presence of inflammatory mediators in the synovial fluid of OA patients. These include cytokines, leukotrienes, prostaglandins, growth factors, and plasma proteins such as C-reactive protein, all of which have been associated with disease progression and clinical symptomatology [5,6,7,8]. Vitamin D, essential for skeletal integrity and bone-cartilage metabolism, plays a pivotal role in calcium and phosphorus homeostasis, osteoblastic function, and maintenance of bone mass. Its deficiency has been linked to impaired turnover of articular cartilage and metabolic dysfunctions associated with bone health [9]. Beyond its role in mineral metabolism, vitamin D possesses immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory properties that allow it to regulate the expression of immune-related factors. Observational studies have reported associations between low vitamin D levels and chronic inflammatory diseases, including inflammatory bowel disease, chronic kidney disease, hepatic inflammation, and RA [10,11,12]. However, data evaluating the relationship between serum 25(OH) D concentrations and inflammatory biomarkers in patients with knee OA remain sparse [13]. Among the cytokines implicated in OA pathogenesis, interleukin-6 (IL-6) is a pro-inflammatory mediator involved in autoimmune disease progression, largely through the IL-6/IL-6 receptor signaling axis. Conversely, IL-10 exerts anti-inflammatory effects by modulating antigen presentation and promoting tissue repair. It is secreted by a variety of immune cells, including regulatory T cells and immature dendritic cells. Notably, vitamin D enhances the production of IL-10 while simultaneously suppressing IL-6 secretion, highlighting a potential regulatory axis relevant to OA pathology. Given the significant immunoregulatory functions of vitamin D and its interaction with key cytokines involved in inflammation, the present study aims to examine the correlation between serum vitamin D levels and circulating IL-6 and IL-10 in patients with primary knee OA. By identifying these associations, the study seeks to contribute to the early diagnostic framework of knee OA and inform timely interventions to potentially mitigate disease progression.

After obtaining institutional ethics committee approval [SU/SMS&R/76-A/2023/116 dated 02.05.2023], a cross-sectional observational analytical investigation was conducted from May 2023 to June 2024 in the Department of Orthopaedics, School of Medical Sciences and Research, Sharda University, Greater Noida. The study population was recruited from patients attending the orthopedic outpatient department who met the defined inclusion and exclusion criteria. A total of 80 participants were enrolled.

Study participants

Participants included individuals over the age of 45 years with either unilateral or bilateral knee pain, where one knee was predominantly symptomatic. Radiological confirmation of primary knee OA was performed using the Kellgren and Lawrence (K&L) grading system.

Inclusion criteria

Patients aged above 45 years with radiologic diagnosis of primary knee OA according to the K&L grading system, and a Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score greater than 3 were included.

Exclusion criteria

Patients who had used anti-inflammatory medications in the past 7 days or had taken vitamin D supplementation within the past month were excluded. Those diagnosed with secondary OA were also excluded from the study.

Procedure

Eligible patients presenting with bilateral knee pain were evaluated clinically and radiologically. Based on the inclusion and exclusion criteria, 80 patients were selected. Blood samples were collected and analyzed for serum vitamin D, IL-6, and IL-10 levels. Each participant was assessed using the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Arthritis Index (WOMAC) score and the VAS for pain. Participants were stratified into two groups based on their vitamin D status: Vitamin D sufficient and vitamin D deficient.

Scoring systems

K&L Classification of Knee OA was used for grading of OA knee. WOMAC and VAS scoring tools were employed to quantify functional impairment and pain intensity, respectively.

Statistical analysis

Data were compiled in Microsoft Excel and analyzed using IBM Statistical Package for the Social Sciences version 26.0, IBM Corp, Illinois, USA. The Kolmogorov–Smirnov test was used to assess the normality of distribution for continuous variables. Quantitative data were expressed as mean and standard deviation. Qualitative variables were presented as frequencies and percentages and represented graphically. Chi-square tests were applied to assess associations between categorical variables. For comparison of continuous variables between groups, Student’s t-test was used. Correlation between continuous variables was evaluated using Karl Pearson’s coefficient of correlation and visualized with scatter plots. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Participant demographics

Seventy-nine patients (50 female, 29 male) aged 45–85 years (mean 57.3 ± 8.3; median 57.0) were included. The largest age stratum was 50–54 years (25.3%), followed by 45–49 (17.7%) and 55–59 (19.0%); remaining strata ranged from 1.3% to 13.9%. K&L grading classified 21 patients (26.6%) as OA Grade 2, 27 (34.1%) as Grade 3, and 32 (40.5%) as Grade 4 (Table 1).

Table 1: Participant demographics

Serum biomarkers and vitamin D status

Mean serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D₃ was 27.9 ± 12.2 ng/mL (median 25.0; range 9.2–69.7), IL-6 65.8 ± 91.0 pg/mL (median 32.0; range 7.3–700), and IL-10 43.5 ± 28.6 pg/mL (median 36.0; range 8.0–166). Vitamin D status was normal in 30 patients (37.5%), insufficient in 26 (32.9%), and deficient in 24 (30.4%). Subgroup analysis showed comparable vitamin D₃ concentrations across OA grades (Grade 2: 28.7 ± 11.9; Grade 3: 29.8 ± 14.2; Grade 4: 27.2 ± 10.9 ng/mL). Wide inter-individual variability in IL-6 and IL-10 (SD > mean) reflected heterogeneous systemic inflammation (Table 2).

Table 2: Biomarkers by Vitamin D status

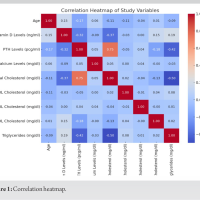

Welch’s analysis of variance (ANOVA) confirmed a lack of variation in vitamin D₃, IL-6, and IL-10 across OA grades (all p > 0.05). Conversely, IL-6 differed significantly by vitamin D status (F2,362 = 9.06; P < 0.001), with higher levels in deficient patients compared to insufficient (mean difference 78.7 pg/mL; P = 0.003) and normal (difference 99.5 pg/mL; P < 0.001). IL-6 differed significantly across vitamin D status groups (ANOVA P < 0.001; Fig. 1), with highest levels in the deficient group. By contrast, IL-10 did not vary significantly (P = 0.118).

Figure 1: Serum interleukin-6 (IL-6) and IL-10 levels stratified by vitamin D status. Bar charts (mean ± Standard deviation) of IL-6 (blue) and IL-10 (red) concentrations in patients with normal (≥30 ng/mL), insufficient (20–29 ng/mL), and deficient (<20 ng/mL) vitamin D₃. Analysis of variance P-value displayed above each cytokine group.

Clinical scores

Mean VAS pain was 6.89 ± 1.39 (median 7; range 4–9). WOMAC pain subscores averaged 17.5 ± 2.76 (median 18; range 11–24), and functional subscores 49.5 ± 8.95 (median 49; range 28–64). No significant differences in VAS, WOMAC pain, or functional scores were observed among vitamin D status groups (all P > 0.05).

Correlation analyses

Pearson’s correlation revealed an inverse relationship between serum vitamin D₃ and IL-6 (r = –0.444; P < 0.001; Fig. 2). Associations with IL-10 (r = –0.174; P = 0.124), VAS (r = –0.167; P = 0.274), WOMAC pain (r = –0.099; P = 0.518) and functional score (r = –0.019; P = 0.903) were negative but non-significant (Table 3).

Figure 2: Inverse correlation between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D₃ and interleukin-6 (IL-6) in primary knee osteoarthritis. Scatter plot of individual patient values for serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D₃ (ng/mL) on the x-axis versus serum IL-6 (pg/mL) on the y-axis. The solid line is Pearson’s regression (r = –0.444, P < 0.001).

Table 3: Correlation of Vitamin D₃ with biomarkers and clinical scores

Overall, results indicate an inverse association between vitamin D3 status and pro-inflammatory IL-6 but no clear link to clinical severity measures or anti-inflammatory IL-10.

In our bilateral knee OA cohort, a distinct inverse relationship emerged between serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D₃ and IL-6. Patients exhibiting vitamin D deficiency displayed notably elevated IL-6 levels compared to those with normal or marginally insufficient vitamin D. Conversely, IL-10 levels remained unaffected across varying vitamin D statuses. Clinical indicators, such as pain intensity and functional assessments, similarly showed no meaningful correlation with serum vitamin D, IL-6, or IL-10 levels. The observation that IL-6 increases in the context of vitamin D deficiency aligns closely with previous findings reported by Amini Kadijani et al. [14] and Putra et al., [15]. This association supports the hypothesis that insufficient vitamin D amplifies pro-inflammatory cytokine release within osteoarthritic joints. IL-6 notably enhances the expression of matrix-degrading enzymes and promotes inflammatory activity in synovial tissues, offering a plausible biochemical route toward cartilage breakdown. Furthermore, IL-6’s soluble receptor-driven trans-signaling mechanism contributes to pathogenic activities in cartilage cells and synovial lining cells. IL-10 concentrations showed stability irrespective of vitamin D levels, consistent with other studies involving individuals with advanced OA. Interestingly, this finding diverges from experimental evidence indicating vitamin D stimulates IL-10 production in laboratory-grown cartilage cells and macrophages. Such inconsistency may stem from shifts in the anti-inflammatory response linked to disease progression. Initially, OA might trigger compensatory increases in IL-10 production, while prolonged disease potentially exhausts this adaptive mechanism. Clinical severity, assessed through VAS and WOMAC scores, demonstrated no associations with serum vitamin D or IL-6 in our participants. This outcome parallels results from randomized supplementation studies, wherein correcting vitamin D deficiency did not reliably improve patient-reported outcomes for pain or joint function [16,17,18]. However, this contrasts with meta-analytic findings indicating modest symptomatic relief following vitamin D therapy [19]. Discrepancies among studies could arise from differences in design, patient selection criteria, and baseline disease severity. From a biological standpoint, vitamin D supports cartilage integrity by activating the Nrf2–KEAP1 antioxidant defense system in chondrocytes, thereby reducing oxidative damage. In addition, vitamin D suppresses matrix-degrading enzyme expression and promotes cartilage matrix formation. Its deficiency might disrupt this protective equilibrium, augmenting cartilage breakdown alongside IL-6-driven enzyme induction [20,21]. IL-6-mediated signaling splits into two distinct modes: classical signaling through membrane-bound receptors, potentially beneficial in certain contexts, and the pro-inflammatory trans-signaling pathway through widespread gp130 expression [22,23]. While our data do not delineate between these mechanisms explicitly, they highlight the broader pathological implications of elevated IL-6 associated with reduced vitamin D. IL-10, meanwhile, possesses cartilage-preserving actions primarily mediated through the JAK-STAT pathway, suppressing enzyme activity and supporting synthesis of crucial cartilage matrix components. Transient increases in IL-10 after physical exercise suggests therapeutic potential, particularly in early OA knee [24,25]. The absence of a clear IL-10 and vitamin D association in our data might reflect advanced disease chronicity and methodological constraints inherent in cross-sectional research. Longitudinal analyses would help clarify whether replenishing vitamin D can reinstate normal IL-10 responses. Our results align closely with existing intervention studies. For instance, Barker et al., documented unchanged IL-6 and IL-10 serum levels after 2 years of vitamin D treatment, despite normalizing vitamin D status [26]. Modifiable factors such as obesity, muscle weakness, and improper limb alignment interact intricately with vitamin D metabolism. Fat tissue stores vitamin D and concurrently secretes IL-6, amplifying inflammatory stress. Weak thigh muscles reduce joint support and increase cartilage strain. Addressing these interconnected elements alongside vitamin D restoration warrants a comprehensive study. Our study carries inherent limitations, notably its cross-sectional design, restricting any causal conclusions. Excluding individuals with severe OA knee stages confines our findings to those with mild-to-moderate disease. Synovial fluid cytokine analyses and detailed examination of IL-6 signaling pathways were not conducted. Future investigations should incorporate repeated measurements over time, assessment of intra-articular biomarkers, and functional evaluation of cytokine-driven cellular responses.

Serum levels of vitamin D₃, IL-6, and IL-10 remained consistent across OA grades, indicating no link to disease severity. However, IL-6 showed a significant inverse correlation with vitamin D₃, with deficient patients exhibiting elevated IL-6 levels. IL-10 levels were unaffected by vitamin D status, and its weak inverse trend lacked statistical significance. No associations were found between these biomarkers and clinical scores. These findings suggest that vitamin D₃ may influence inflammatory activity, particularly IL-6, in OA. Longitudinal studies are needed to determine whether correcting vitamin D deficiency can modulate cytokine profiles and alter OA progression.

• Vitamin D deficiency is significantly associated with elevated IL-6 levels, indicating a potential role for vitamin D in modulating inflammatory responses in primary knee osteoarthritis.

• Serum levels of vitamin D₃, IL-6, and IL-10 do not correlate with OA severity or patient-reported outcomes, suggesting limited utility of these biomarkers in assessing clinical progression.

• Restoring vitamin D sufficiency may help regulate inflammatory cytokine profiles, particularly IL-6, but longitudinal studies are needed to confirm its therapeutic impact on OA progression.

References

- 1. Heidari B. Knee osteoarthritis prevalence, risk factors, pathogenesis and features: Part I. Caspian J Intern Med 2011;2:205-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Peat G, Thomas E, Duncan R, Wood L, Hay E, Croft P. Clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: Performance in the general population and primary care. Ann Rheum Dis 2006;65:1363-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Yadav R, Verma AK, Uppal A, Chahar HS, Patel J, Pal CP. Prevalence of primary knee osteoarthritis in the Urban and rural population in India. Indian J Rheumatol 2022;17:239. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Sokolove J, Lepus CM. Role of inflammation in the pathogenesis of osteoarthritis: Latest findings and interpretations. Ther Adv Musculoskelet Dis 2013;5:77-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. De Roover A, Escribano-Núñez A, Monteagudo S, Lories R. Fundamentals of osteoarthritis: Inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2023;31:1303-11. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Batarfi WA, Yunus MH, Hamid AA, Maarof M, Abdul Rani R. Breaking down osteoarthritis: Exploring inflammatory and mechanical signaling pathways. Life (Basel) 2025;15:1238. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Rahmati M, Mobasheri A, Mozafari M. Inflammatory mediators in osteoarthritis: A critical review of the state-of-the-art, current prospects, and future challenges. Bone 2016;85:81-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Nees TA, Rosshirt N, Zhang JA, Reiner T, Sorbi R, Tripel E, et al. Synovial cytokines significantly correlate with osteoarthritis-related knee pain and disability: Inflammatory mediators of potential clinical relevance. J Clin Med 2019;8:1343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Laird E, Ward M, McSorley E, Strain JJ, Wallace J. Vitamin D and bone health: Potential mechanisms. Nutrients 2010;2:693-724. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Yin K, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D and inflammatory diseases. J Inflamm Res 2014;7:69-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Zhao S, Qian F, Wan Z, Chen X, Pan A, Liu G. Vitamin D and major chronic diseases. Trends Endocrinol Metab 2024;35:1050-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Álvarez-Mercado AI, Mesa MD, Gil Á. Vitamin D: Role in chronic and acute diseases. Encyclopedia Human Nutrition 2023;1:535-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Zhao H, Zhao Y, Fang Y, Zhou W, Zhang W, Peng J. The relationship between novel inflammatory markers and serum 25-hydroxyvitamin D among US adults. Immun Inflamm Dis 2025;13:e70115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Amini Kadijani A, Bagherifard A, Mohammadi F, Akbari A, Zandrahimi F, Mirzaei A. Association of serum vitamin D with serum cytokine profile in patients with knee osteoarthritis. Cartilage 2021;13:1610S-8S. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Putra KM, Partan RU, Hermansyah H, Saleh MI. The role of 25-hydroxy vitamin D and cartilage oligomeric matrix protein (COMP) serum in knee osteoarthritis. Indones J Rheumatol 2024;16:823-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Liu D, Meng X, Tian Q, Cao W, Fan X, Wu L, et al. Vitamin D and multiple health outcomes: An umbrella review of observational studies, randomized controlled trials, and mendelian randomization studies. Adv Nutr 2022;13:1044-62. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Albasheer O, Abdelwahab SI, Alqassim A, Alessa H, Madkhali A, Hakami A, et al. Effects of vitamin D supplementation on symptoms and clinical outcomes in adults with different baseline vitamin D levels: An interventional study. J Health Popul Nutr 2025;44:176. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Zhuang Y, Zhu Z, Chi P, Zhou H, Peng Z, Cheng H, et al. Efficacy of intermittent versus daily vitamin D supplementation on improving circulating 25(OH)D concentration: A Bayesian network meta-analysis of randomized controlled trials. Front Nutr 2023;10:1168115. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Zhao ZX, He Y, Peng LH, Luo X, Liu M, He CS, et al. Does vitamin D improve symptomatic and structural outcomes in knee osteoarthritis? A systematic review and meta-analysis. Aging Clin Exp Res 2021;33:2393-403. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Garfinkel RJ, Dilisio MF, Agrawal DK. Vitamin D and its effects on articular cartilage and osteoarthritis. Orthop J Sports Med 2017;5:2325967117711376. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Gao X, Min Y, Lin R, Liang D, Zhang M, Xiao Q, et al. Vitamin D alleviates osteoarthritis progression by targeting cartilage and subchondral bone via Myd88-TAK1-ERK axis suppression. Drug Des Devel Ther 2025;19:5855-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Reeh H, Rudolph N, Billing U, Christen H, Streif S, Bullinger E, et al. Response to IL-6 trans- and IL-6 classic signalling is determined by the ratio of the IL-6 receptor α to gp130 expression: Fusing experimental insights and dynamic modelling. Cell Commun Signal 2019;17:46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Millrine D, Jenkins RH, Hughes ST, Jones SA. Making sense of IL-6 signalling cues in pathophysiology. FEBS Lett 2022;596:567-88. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Saraiva M, Vieira P, O’Garra A. Biology and therapeutic potential of interleukin-10. J Exp Med 2019;217:e20190418. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Behrendt P, Preusse-Prange A, Klüter T, Haake M, Rolauffs B, Grodzinsky AJ, et al. IL-10 reduces apoptosis and extracellular matrix degradation after injurious compression of mature articular cartilage. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2016;24:1981-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Barker T, Schneider ED, Dixon BM, Henriksen VT, Weaver LK. Supplemental vitamin D enhances the recovery in peak isometric force shortly after intense exercise. Nutr Metab (Lond) 2013;10:69. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]