This rare case report contributes that anterior open-wedge flexion valgus osteotomy is an effective technique to correct post-traumatic genu recurvatum by restoring posterior tibial slope and coronal alignment, leading to resolution of instability and full functional recovery.

Dr. Pradeep Patel, Department of Orthopedics, Shree Narayana Hospital, Raipur, Chhattisgarh, India. E-mail: drpradeep1903@gmail.com

Introduction: Traumatic genu recurvatum is uncommon condition but functionally significant deformity of the knee, most often resulting from loss of the posterior tibial slope following proximal tibial fractures. This condition can lead to pain, instability, and limitations in daily activities. Surgical correction aims to restore both sagittal and coronal alignment to alleviate symptoms and improve function. We present a case of post-traumatic genu recurvatum secondary to a malunited bicondylar proximal tibial fracture, successfully managed with anterior open-wedge flexion valgus osteotomy.

Case Report: We report the case of a 39-year-old male presenting 10 months post-injury with symptomatic genu recurvatum and instability following a malunited bicondylar proximal tibial fracture. Radiological evaluation revealed significant loss of posterior slope (−30°), varus malalignment 10°, and decreased (medial proximal tibial angle −76.9°). An anterior open-wedge flexion valgus osteotomy with tibial tubercle osteotomy was performed to restore the sagittal and coronal alignment. At 3 months, the patient achieved full functional recovery with no recurvatum or instability.

Conclusion: This case highlights the importance of recognizing post-traumatic genu recurvatum, particularly when associated with proximal tibial malunion and the effectiveness of anterior slope correction osteotomy in managing post-traumatic genu recurvatum.

Keywords: Genu recurvatum, flexion valgus osteotomy, post-traumatic deformity, posterior tibial slope.

Genu recurvatum, or hyperextension deformity of the knee, is a multifactorial condition. It may be congenital, neuromuscular, or acquired. Among acquired causes, trauma is a key etiology, particularly in cases of malunion after proximal tibial fractures. When the posterior tibial slope is lost, there is a predisposition to posterior tibial translation, altered biomechanics, and pseudo-instability, even in the presence of intact posterior cruciate ligaments (PCLs) [1,2]. Restoring the posterior slope is essential for correcting the biomechanical derangements. Several surgical techniques have been described, with anterior open-wedge flexion osteotomy being the most employed for slope restoration [3]. When associated with coronal deformity, simultaneous correction is necessary. We present a case of post-traumatic genu recurvatum corrected with an anterior open-wedge tibial osteotomy, based on principles reported by Ramos Marques et al. [4].

A 39-year-old male presented with complaints of the left knee pain during walking and episodes of instability. He reported a history of a bicondylar proximal tibial fracture sustained 10 months prior due to a road traffic accident, which was managed conservatively. Over time, he developed progressive knee hyperextension and functional limitations due to malunited proximal tibia fracture. Knee was examined thoroughly for ligamentous laxity, stress testing, and range of motion.

On clinical examination

- Gait analysis: Varus thrust observed during ambulation and varus stress (Fig. 1a)

Figure 1: Clinical demonstration of deformity. (a) Varus deformity on giving varus stress. (b) Genu recurvatum with increased heel height demonstrating 8 cm side to side difference.

- Knee alignment: Apparent genu recurvatum deformity with a heel height discrepancy of 8 cm compared to the contralateral side (Fig. 1b)

- Ligamentous assessment: Lachman and posterior drawer tests revealed stable endpoints; however, pseudo-laxity of the PCL was noted

- Range of motion: Full flexion achieved; hyperextension beyond neutral observed.

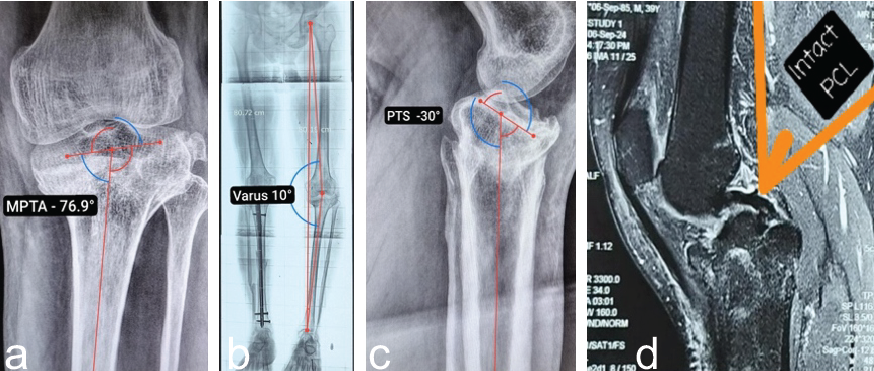

Radiographic evaluation

- Anteroposterior (AP) view: Varus deformity measuring 10°, with a medial proximal tibial angle (MPTA) of 76.9° (Fig. 2a and b).

- Lateral view: Posterior tibial slope reduced to −30°, indicating significant loss of normal posterior inclination (Fig. 2c).

- Computed tomography (CT): Confirmed the decreased posterior tibial slope and provided detailed assessment for surgical planning.

- Magnetic resonance imaging: Confirmed the integrity of PCL (Fig. 2d).

Figure 2: X-rays of left knee. (a) Anteroposterior view demonstrating MPTA 76.9° and (b) scanogram-varus 10°. (c) Lateral View: posterior (reverse) tibial slope −30°. The posterior tibial slope was quantified relative to the anatomic axis of the tibia, established by connecting mid-diaphyseal reference points located approximately 5 cm and 15 cm distal to the tibial plateau, each defined at the midpoint between the anterior and posterior cortical borders on the sagittal plane, and (d) magnetic resonance imaging showing intact PCL.

The patient was finally diagnosed with post-traumatic genu recurvatum secondary to malunited bicondylar proximal tibial fracture with decreased posterior tibial slope and varus alignment. Patient then planned for anterior open-wedge flexion valgus osteotomy with tibial tubercle osteotomy to correct sagittal and coronal plane deformities.

Surgical technique

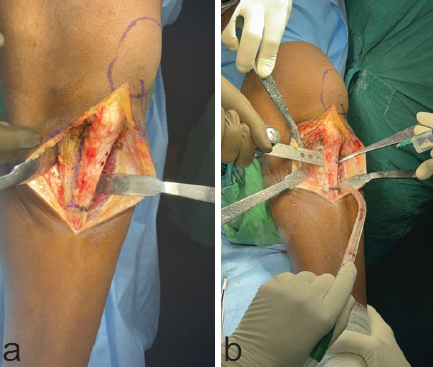

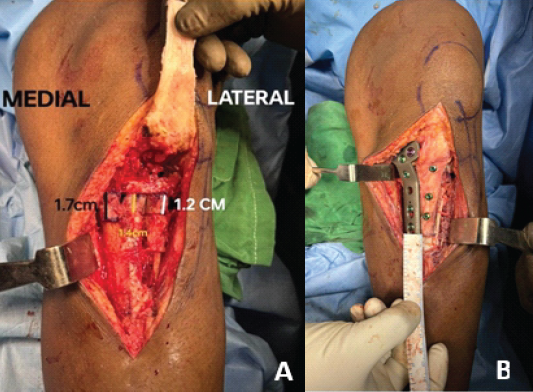

A midline skin incision was made slightly medial to the tibial tuberosity, beginning at the level of the inferior patellar pole and extending approximately 10 cm distally. Full-thickness subcutaneous flaps were carefully elevated on both medial and lateral sides. On the medial side, subperiosteal dissection was carried out beneath the medial collateral ligament extending to the posteromedial aspect of the proximal tibia. Laterally, the tibialis anterior muscle was elevated from the tibial surface (Fig. 3a). The patellar tendon insertion was clearly identified, and the tibial tuberosity was exposed. An osteotomy line was marked along the anterior tibial crest, extending about 7 cm distally on both sides of the tibial tubercle, followed using a power saw to cut a bone block (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: Left knee. (a) Exposure of tibial tuberosity with elevation of full thickness flap medially and laterally and (b) osteotomy of the tibial tubercle using saw.

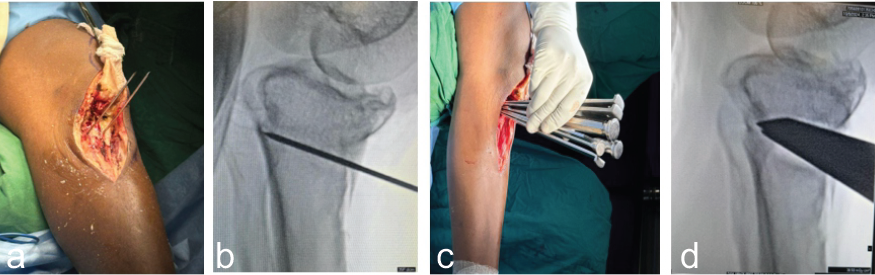

A 7-cm segment of the tibial tubercle, maintaining appropriate width and thickness, was mobilized, along with the attached patellar tendon as a single unit. This segment was wrapped in gauze soaked with vancomycin and retracted proximally for protection (Fig. 4a). With the knee flexed to 30° and posteriorly supported, a C-arm was used to obtain a lateral fluoroscopic view. The proximal tibial osteotomy site was identified 3 cm below the joint line. Two parallel monocortical K-wires were inserted obliquely under fluoroscopic guidance, starting from distal to proximal along the visible previous fracture line and parallel to posterior tibial slope, either side of the tibial tubercle bed. These wires were advanced until they abutted the posterior tibial cortex, aiming for a point ending with previous fracture line, approximately 2.5 cm distal to the joint line, as verified by fluoroscopy (Fig. 4a and b). After the osteotomy lines were completed using a power saw, osteotomes were gently used to reach close-within approximately 5 mm-to the posterior cortex across the full transverse diameter of the tibia. Care was taken to preserve the posterior cortex and avoid fracture propagation. To facilitate controlled opening of the osteotomy, multiple 2.5 mm drill holes were placed at the intended hinge area in the posterior cortex to soften it. Multiple stacked osteotome was introduced anteriorly to gradually open the osteotomy site (Fig. 4c and d).

Figure 4: Left knee. (a and b) Intraoperative and fluoroscopic image insertion of two parallel guide wires along the previous fracture line and (c and d) intraoperative and fluoroscopic image of stacked osteotomes used for opening the desired wedge.

Under fluoroscopic control, the medial side was opened more to achieve the desired coronal plane correction based on pre-operative planning. To maintain the created gap, wedge-shaped tricortical autografts harvested from the iliac crest. Graft was prepared in differential manner and inserted accordingly to correct varus along with slope. A 17-mm-thick graft was placed on the medial side to provide medial column support, while a 12-mm-thick graft was positioned laterally. A central block of 14 mm thickness was interposed between the two to stabilize the construct (Fig. 5a). The osteotomy was stabilized using a high tibial osteotomy (HTO) plate (Fig. 5b). Finally, the previously elevated tibial tubercle was reattached using a cancellous screw, ensuring restoration of appropriate patellar height and alignment and avoiding patella baja (Fig. 5b). Fixation of tibial tuberosity itself acts as a biological plate providing stability to osteotomy site.

Figure 5: (a) Insertion of differential thickness bone graft to correct varus and hyperextension both simultaneously and (b) a Tomofix HTO plate is fixed under fluoroscopic guidance, just medial to tibial tuberosity osteotomy line, along with fixation of tibial tuberosity with 3 CC screw as “biological plate.”

Post-operative course and follow-up

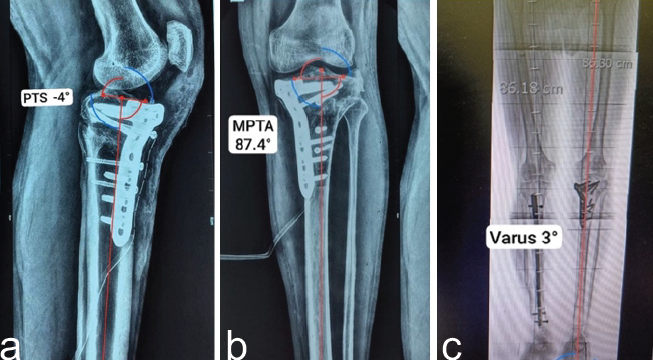

On post-operative radiograph, there is marked correction of deformity in both planes with residual varus of mere 3° with MPTA-87.4°, whereas tibial slope was restored up to −4° (Fig. 6a, b, c).

Figure 6: (a) Post-operative anteroposterior radiograph showing restored MPTA 87.4° after valgus osteotomy demonstrating correction (10.5°) from 76.9°, (b) post-operative lateral radiograph showing correction of posterior (reversed) tibial slope from −30° to −4°, and (c) post-operative scanogram illustrating residual post-operative varus of merely 3° making it like normal opposite limb (constitutional varus).

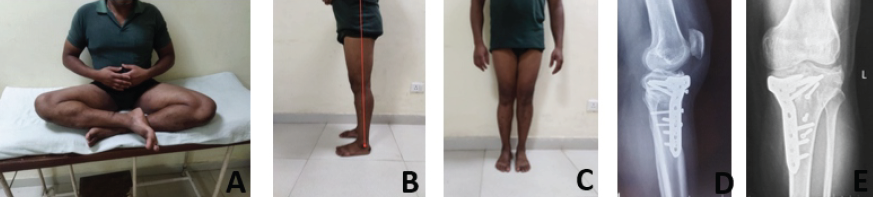

The patient was mobilized with protected partial weight-bearing from the 4th post-operative week. By the end of 8th week, the patient was advised to walk full weight-bearing with support. At 3 months follow-up, the patient had restored nearly full range of motion. Recurvatum deformity was completely corrected with no extensor lag or fixed flexion deformity. The patient ambulated without support or discomfort (Fig. 7a, b, c, d). Post-operative radiograph at 1 year showed excellent healing at the osteotomy site and no collapse at fracture site with maintained alignment of the limb (Fig. 8a, b, c, d).

Figure 7: At 3-month post-operative. (a) Restoration of physiological heel height with no clinical evidence of knee hyperextension deformity. (b) Achieved functional knee range of motion from 0° extension to 130° flexion. (c) Ambulating with a stable gait pattern and without evidence of dynamic varus thrust. (d) Able to perform squatting and sit-to-stand maneuvers comfortably, indicating satisfactory quadriceps control and functional knee flexion.

Figure 8: At 1 year follow-up. (a) Comfortably sitting cross legged, (b) no recurvatum, (c) maintained alignment similar bilaterally, and (d and e) excellent consolidation of bone gap without collapse.

Posterior tibial slope plays a pivotal role in the functional kinematics of the knee. A reduction in slope, especially following trauma, increases posterior tibial translation during flexion and reduces the efficiency of the PCL. This phenomenon leads to pseudolaxity even when the PCL remains structurally intact. Traumatic genu recurvatum due to loss of posterior slope is uncommon but significantly impacts function. Ramos Marques et al. emphasized that when conservative treatment fails, surgical restoration of tibial slope using anterior opening wedge osteotomy is effective [4]. Their case series demonstrated improved biomechanics and stability after such corrections. The key to successful surgical correction lies in – accurate identification of deformity in both sagittal and coronal planes, use of planning tools (CT, long-leg alignment films), and execution of a controlled anterior open-wedge osteotomy without violating the posterior cortex. In our case, we followed the principles outlined by Ramos Marques et al. [4], adapting their technique using differential bone grafting to achieve dual-plane correction. Fixation with a locking HTO plate ensured early mobilization, whereas some literature advocates the use of screws [5] and staples [6] for fixing the osteotomy. The importance of tibial tubercle osteotomy cannot be overstated. It allows adequate exposure and prevents iatrogenic patella baja, which is a frequent complication of anterior opening wedge osteotomies. Patella baja is a frequently encountered post-operative complication following open-wedge HTO, especially when the osteotomy is performed proximal to the tibial tubercle and the patellar tendon insertion [7]. To preserve patellofemoral kinematics and maintain appropriate patellar height, a concomitant tibial tubercle osteotomy is indicated [8]. Literature supports that restoring posterior slope in these patients reduces posterior instability and improves gait, quadriceps efficiency, and knee kinematics [4,9,10]. Long-term results show low recurrence of deformity and high patient satisfaction when precise alignment and fixation are achieved [3].

Anterior open-wedge flexion valgus osteotomy is a reliable technique for managing post-traumatic genu recurvatum due to decreased posterior tibial slope along with varus deformity. It addresses both biomechanical and functional impairments. When combined with tibial tubercle osteotomy and appropriate stable fixation, it leads to excellent clinical outcomes.

Post-traumatic genu recurvatum due to loss of posterior tibial slope is a rare but functionally disabling condition. Anterior open-wedge flexion valgus osteotomy, combined with tibial tubercle osteotomy, offers a reliable solution for restoring sagittal and coronal alignment, improving knee biomechanics, and achieving excellent clinical outcomes.

References

- 1. Loudon JK, Goist HL, Loudon KL. Genu recurvatum syndrome. J Orthop Sports Phys Ther 1998;27:361-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Giffin JR, Stabile KJ, Zantop T, Vogrin TM, Woo SL, Harner CD. Importance of tibial slope for stability of the posterior cruciate ligament deficient knee. Am J Sports Med 2007;35:1443-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Dean RS, Graden NR, Kahat DH, DePhillipo NN, LaPrade RF. Treatment for symptomatic genu recurvatum: A systematic review. Orthop J Sports Med 2020;8:2325967120944113. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Ramos Marques N, Morais B, Barreira M, Nóbrega J, Ferrão A, Torrinha Jorge J. Anterior slope correction-flexion osteotomy in traumatic genu recurvatum. Arthrosc Tech 2022;11:e889-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Zein AM, Mahmoud Hassan AZ, Saleh Elsaid AN. Biological bone plate and iliac bone autograft for proximal tibial slope changing osteotomy in genu recurvatum. Arthrosc Tech 2022;11:e989-98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Reddy KR, Reddy NS, Prakash N. Anterior open-wedge osteotomy to correct sagittal and coronal malalignment in a case of failed high tibial osteotomy and failed posterior cruciate ligament reconstruction. Arthrosc Tech 2024;13:103032. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Fan JC. Open wedge high tibial osteotomy: Cause of patellar descent. J Orthop Surg Res 2012;7:3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Chen YN, Chang CW, Li CT, Chen CH, Chung CR, Chang CH, et al. Biomechanical investigation of the type and configuration of screws used in high tibial osteotomy with titanium locking plate and screw fixation. J Orthop Surg Res 2019;14:35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Rodriguez AN, Schreier F, Carlson GB, LaPrade RF. Proximal tibial opening wedge osteotomy for the treatment of posterior knee instability and genu recurvatum secondary to increased anterior tibial slope. Arthrosc Tech 2021;10:e2717-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Gaskill TR, Pierce CM, James EW, LaPrade RF. Anterolateral proximal tibial opening wedge osteotomy to treat symptomatic genu recurvatum with valgus alignment: A case report. JBJS Case Connector 2014;4:e71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]