Decompression alone, without fusion, is effective for lumbar stenosis in stable skeletally mature achondroplasia patients.

Dr. Dileepan Chakrawarthi, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, One Health Super Speciality Hospital, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: chakdileep@gmail.com

Introduction: Achondroplasia, the most common skeletal dysplasia, often presents with congenital lumbar spinal stenosis. In skeletally mature adults without instability, the choice between decompression alone and decompression with fusion remains debated.

Case Report: A 21-year-old male with achondroplasia presented with progressive neurogenic claudication and bilateral extensor hallucis longus weakness. Magnetic resonance imaging showed multilevel stenosis (L1–L5) from congenitally short pedicles and ligamentum flavum hypertrophy, without instability. He underwent L1–L5 laminectomy and flavectomy without instrumentation. At 2-year follow-up, neurological function was sustained with no recurrence or instability.

Conclusion: Adult achondroplasia patients with preserved stability may benefit from decompression alone, avoiding the added morbidity of fusion. Careful patient selection, early intervention, and meticulous technique are key to good long-term outcomes. Multilevel decompression without fusion can be an effective, durable option for lumbar stenosis in skeletally mature achondroplasia patients when stability is intact.

Keywords: Achondroplasia, lumbar spinal stenosis, decompression, laminectomy, case report.

Achondroplasia is the most common form of skeletal dysplasia and the leading cause of disproportionate short stature, with an estimated incidence of about 1 in 25,000 live births [1,2]. It follows an autosomal dominant inheritance pattern and is caused by a mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene, which impairs chondrocyte proliferation in the proliferative zone of the physis [3]. Approximately 80% of cases arise from new, sporadic mutations. Individuals with achondroplasia exhibit characteristic features that include disproportionate short stature, macrocephaly, frontal bossing, rhizomelic shortening of the limbs, and spinal deformities such as thoracolumbar kyphosis, lumbar hyperlordosis, and spinal stenosis [4,5,6].

In the spine, altered development of the posterior elements results in early fusion of the pedicles with the vertebral body, producing short pedicles and thickened laminae. The combination of reduced interpedicular distance, decreased vertebral body height, and shortened pedicles narrows the spinal canal in both the anteroposterior and transverse dimensions. This congenital narrowing can lead to compression of the spinal cord and nerve Roots, presenting clinically as neurogenic claudication, radiculopathy, or myelopathy, depending on the level of involvement [6,7,8,9,10,11].

While all patients with achondroplasia have a congenitally narrow lumbar canal, the incidence of neurological symptoms varies widely, ranging from 0% to 78% [2,11]. Only a small percentage, about one-third of people with symptoms, requires surgery. While concurrent instrumented fusion remains controversial, surgical decompression is still the cornerstone of treatment.

Here, we report the case of an adult patient with achondroplasia presenting with multilevel lumbar spinal stenosis and severe neurogenic claudication, successfully treated with decompression alone. We also review relevant literature to further explore the indications for fusion in this patient population.

A 21-year-old Indian male with achondroplasia presented with progressive difficulty in walking for the past 3 years. He reported persistent pain and discomfort in the lower back and both legs during this period. One month before presentation, his symptoms worsened, with post-exertional lumbar pain accompanied by numbness and pain in both lower limbs (leg pain greater than back pain). Over the subsequent 3 weeks, his condition deteriorated to the point where he was completely unable to walk.

Clinical examination revealed disproportionate short stature (height 132 cm) with short limbs, a relatively long trunk, frontal bossing, and a depressed nasal bridge (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Clinical picture of patient showing typical features of Achondroplasia.

Neurological examination showed bilateral weakness of the extensor hallucis longus (EHL) with motor power of 2/5 in the L5 myotome on both sides; all other myotomes had normal strength (5/5). Sensory examination demonstrated intact light touch, vibration, and proprioception in both lower limbs, with normal perianal sensation and voluntary anal contraction. Bowel and bladder functions were preserved.

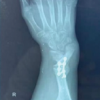

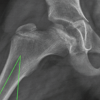

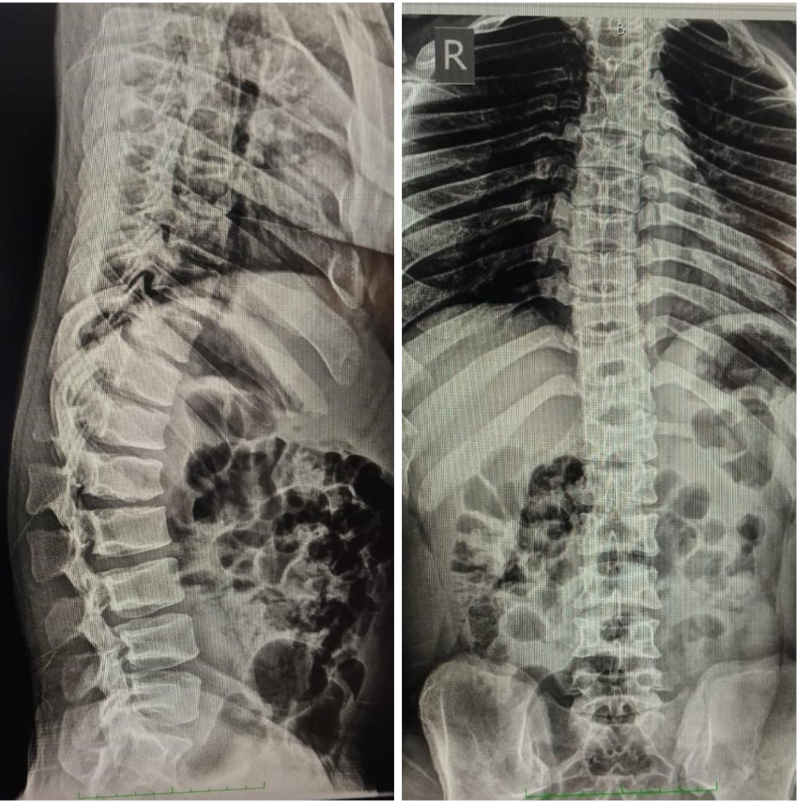

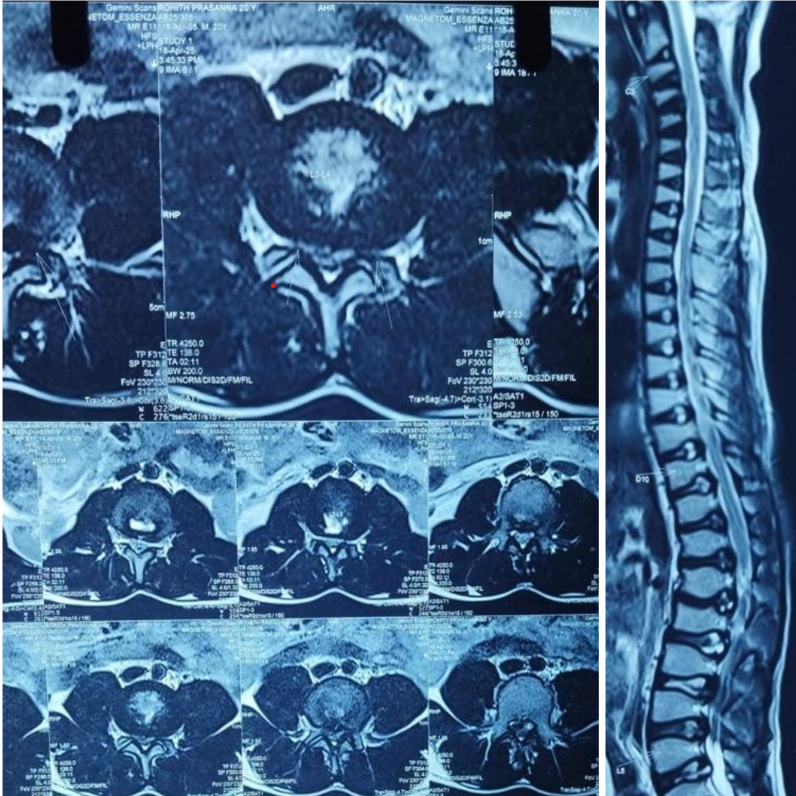

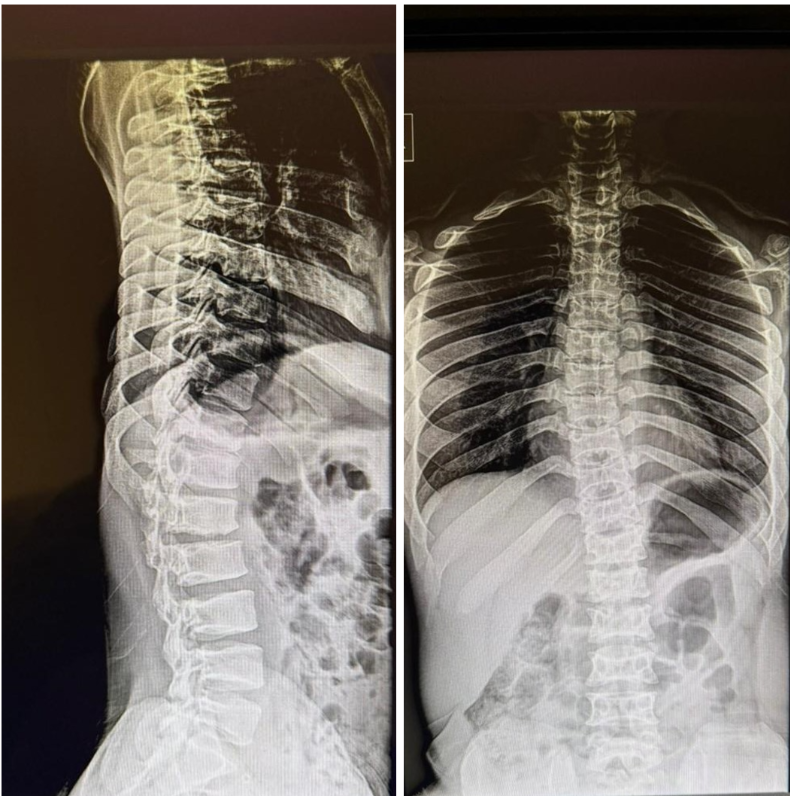

Radiological evaluation included plain radiographs, which showed reduced interpedicular distance and short pedicles in the lumbar spine, consistent with congenital canal stenosis (Fig. 2). Computed tomography confirmed the presence of short pedicles without evidence of ossified ligamentum flavum (Fig. 3). Magnetic resonance imaging demonstrated multilevel lumbar stenosis from L1 to L5 with thickened ligamentum flavum. Pre-operative Oswestry disability index score was 60%. Routine laboratory investigations were within normal limits.

Figure 2: Pre-operative X-ray.

Figure 3: Magnetic resonance imaging axial and sagittal T2W images showing lumber canal stenosis L1–L5.

Given the diagnosis of severe neurogenic claudication, surgical decompression from L1 to L5 was planned. After obtaining informed consent from the patient and his family, along with explaining the increased perioperative risk, the patient underwent surgery. Using a standard posterior midline approach, laminectomies were performed at L1–L5. Hypertrophied ligamentum flavum was identified and carefully excised, with meticulous dissection to avoid dural injury (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: (Left to right) prone position with vertical bolster with adequate paddings, intraoperative images show L1-L5 facet sparing laminectomy.

The post-operative course was uneventful. Rehabilitation was initiated on post-operative day 3. At 1-month follow-up, the patient reported significant improvement in leg pain, although some residual back pain persisted. At the 2-year follow-up, bilateral EHL strength had improved to 4/5, and functional mobility was maintained (Fig. 5).

Figure 5: Two-year follow-up standing whole spine radiograph shows no evidence of progressive thoracolumbar kyphosis.

Achondroplasia is an autosomal dominant skeletal disorder caused by a characteristic mutation in the fibroblast growth factor receptor 3 (FGFR3) gene [1]. Clinically, it is characterized by rhizomelic shortening of the limbs, macrocephaly, frontal and parietal bossing, and saddle-nose deformity. Spinal manifestations are common and include thoracolumbar kyphosis, lumbar lordosis, and spinal canal stenosis [4,5,6]. Thoracolumbar kyphosis develops in up to 90% of patients with achondroplasia [12].

Spinal stenosis in achondroplasia is classified as congenital developmental stenosis, as described by Arnold et al. [13]. In addition to the congenital narrowing from short pedicles, thickened laminae, and reduced interpedicular distance, these patients may also have degenerative changes, such as intervertebral disc degeneration, hypertrophy of the ligamentum flavum, and facet joint overgrowth, which further compromise the canal diameter [14,15,16]. The incidence of neurological symptoms from lumbar stenosis in achondroplasia varies widely in the literature, ranging from 20% to 78% [2,11], with the lumbar spine being the most frequently affected site [17,18,19].

Our patient presented with progressive neurogenic claudication, bilateral EHL weakness, intact sensation, and preserved bowel and bladder function, suggestive of severe lumbar spinal stenosis. Radiological evaluation in achondroplasia typically reveals shortened vertebral bodies and pedicles, reduced interpedicular distance, and increased pedicle diameter. Ossification of the ligamentum flavum (OLF), while reported in achondroplasia, is rare, with only 11 cases documented in the literature . In our case, OLF was absent, and stenosis was due solely to congenital and degenerative changes from L1 to L5.

Approximately 24% of patients with achondroplasia eventually require surgery for spinal stenosis [23]. Indications, timing, and optimal surgical techniques remain incompletely defined. The primary indication is progressive neurological deficit [15]. Several authors advocate decompression alone for symptomatic cases [20-23], while others recommend decompression with instrumentation to address potential instability [24]. In our patient, we performed L1–L5 laminectomy and flavectomy without instrumentation, given the absence of instability on pre-operative imaging and intraoperative assessment. The patient experienced significant long-term neurological recovery and pain relief, supporting the role of decompression alone in carefully selected cases.

What distinguishes this case from prior reports is the combination of multilevel lumbar stenosis in a young adult with achondroplasia, absence of OLF, and durable clinical improvement without fusion. While fusion may be indicated in cases with pre-operative instability, deformity correction, or when extensive bony resection risks destabilizing the spine, our experience supports that decompression alone can yield excellent functional outcomes when stability is preserved.

From a clinical standpoint, this case emphasizes the importance of individualized surgical planning in achondroplasia-associated spinal stenosis. Thorough radiological evaluation, careful intraoperative assessment of stability, and tailored surgical decompression can achieve lasting symptom relief without the added morbidity of fusion in appropriately selected patients.

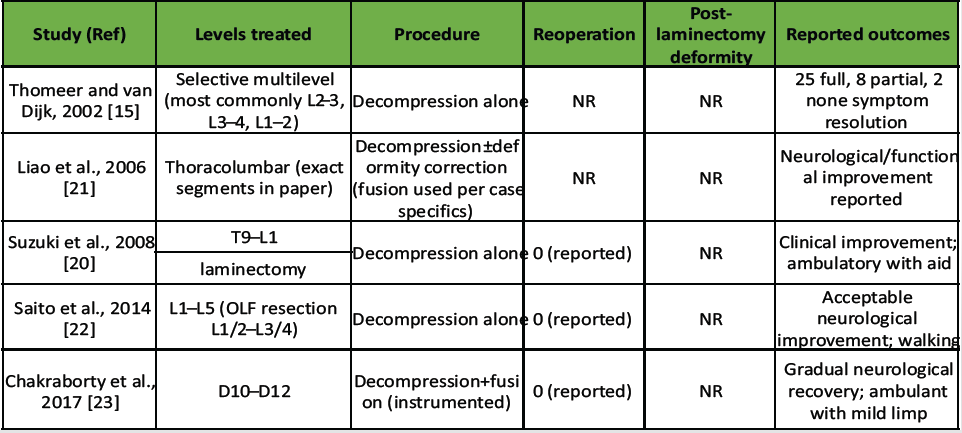

Table 1 Summary of reported adult achondroplasia cases with spinal stenosis, surgical management strategies, and outcomes from the current review. Only studies included in the reference list of this manuscript are presented [15,20,21,22,23].

Table 1: Summary of published studies reporting outcomes of decompression for thoracolumbar/lumbar ossification of the ligamentum flavum

The literature identifies several potential complications in achondroplasia patients undergoing spinal surgery, including dural tears, progressive spinal deformity, and the need for reoperation. In adults, reoperation rates are reported between 25% and 45%, which is notably lower than in the pediatric population, where rates range from 25% to 100% [25]. In children, post-operative kyphotic deformity is the most common reason for reoperation, whereas in adults, recurrent stenosis is more frequently implicated [25].

Post-laminectomy kyphosis is a well-recognized concern in pediatric patients treated with decompression alone. Ain et al. (2006) reported a 100% incidence of post-laminectomy kyphosis in children with achondroplasia managed without instrumentation [26]. In contrast, Pyeritz et al. reported a 9% incidence in adults (2 out of 22 patients) [27]. This difference is ascribed to anatomical and physiological factors; skeletally mature adults have a relatively static spinal structure, while children retain significant axial and peripheral skeletal growth, creating a dynamic environment.

Other reported complications include dural tear and cerebrospinal fluid leakage, with Sun et al. noting an incidence of 32% in spinal stenosis surgery [28]. In our patient, laminectomy for a severely stenotic spinal canal with adhesions of the ligamentum flavum was performed successfully without dural injury, owing to careful dissection and intraoperative vigilance.

Given these risks, achondroplasia patients should be educated about the symptoms of spinal stenosis and encouraged to seek medical evaluation early. Prompt diagnosis and timely surgical decompression are essential to maximize neurological recovery and reduce the likelihood of long-term disability.

Lumbar spinal stenosis in achondroplasia requires a tailored surgical approach based on patient age, spinal stability, and symptom severity. This case demonstrates that in skeletally mature adults without pre-operative instability, multilevel decompression alone can achieve durable neurological recovery and functional improvement. Early diagnosis, timely surgical intervention, and vigilant intraoperative technique are critical to optimizing outcomes and minimizing complications in this unique patient population.

In adult achondroplasia patients with lumbar stenosis and preserved spinal stability, multilevel decompression without fusion is a safe and effective treatment option that minimizes morbidity and ensures sustained neurological recovery.

References

- 1. Shiang R, Thompson LM, Zhu YZ, Church DM, Fielder TJ, Bocian M, et al. Mutations in the transmembrane domain of FGFR3 cause the most common genetic form of dwarfism, achondroplasia. Cell 1994;78:335-42. [Google Scholar]

- 2. McDonald EJ, De Jesus O. Achondroplasia. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2025. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK559263 [Last accessed on 19 May 2025]. [Google Scholar]

- 3. Dubousset J, Masson JC. Spinal disorders: Kyphosis and lumbar stenosis. Basic Life Sci 1988;48:299-303. [Google Scholar]

- 4. Hall JG. The natural history of achondroplasia. Basic Life Sci 1988;48:3-9. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Hurko O, Pyeritz R, Uematsu S. Neurological considerations in achondroplasia. Basic Life Sci 1988;48:153-62. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Nelson MA. Kyphosis and lumbar stenosis in achondroplasia. Basic Life Sci 1988;48:305-11. [Google Scholar]

- 7. Giglio GC, Passariello R, Pagnotta G, Crostelli M, Ascani E. Anatomy of the lumbar spine in achondroplasia. Basic Life Sci 1988;48:227-39. [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jeong ST, Song HR, Keny SM, Telang SS, Suh SW, Hong SJ. MRI study of the lumbar spine in achondroplasia. A morphometric analysis for the evaluation of stenosis of the canal. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2006;88:1192-6. [Google Scholar]

- 9. Yukawa Y, Lenke LG, Tenhula J, Bridwell KH, Riew KD, Blanke KA. comprehensive study of patients with surgically treated lumbar spinal stenosis with neurogenic claudication. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1954-9. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Yamada H, Nakamura S, Tajima M, Kageyama N. Neurological manifestations of pediatric achondroplasia. J Neurosurg 1981;54:49-57. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Ruiz-Garcia M, Tovar-Baudin A, Del Castillo-Ruiz V, Rodriguez HP, Collado MA, Mora TM, et al. Early detection of neurological manifestations in achondroplasia. Childs Nerv Syst 1997;13:208-13. [Google Scholar]

- 12. Srikumaran U, Woodard EJ, Leet AI, Rigamonti D, Sponseller PD, Ain MC. Pedicle and spinal canal parameters of the lower thoracic and lumbar vertebrae in the achondroplast population. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2007;32:2423-31. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Arnoldi CC, Brodsky AE, Cauchoix J, Crock HV, Dommisse GF, Edgar MA, et al. Lumbar spinal stenosis and nerve root entrapment syndromes. Definition and classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1976;115:4-5. [Google Scholar]

- 14. Hamamci N, Hawran S, Biering-Sørensen F. Achondroplasia and spinal cord lesion. Three case reports. Paraplegia 1993;31:375-9. [Google Scholar]

- 15. Thomeer RT, Van Dijk JM. Surgical treatment of lumbar stenosis in achondroplasia. J Neurosurg 2002;96(3 Suppl):292-97. [Google Scholar]

- 16. Kataoka O. A case of achondroplasia occurred palaplasis after trauma. Spinal Surg 1990;1:346-50. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Nakahashi K, Baba H, Takahasi K, Kawahara N, Kikuchi Y, Tomita K. Achondroplasia with ossification of yellow ligament of the thoracic spine: Report of a case. Orthop Surg Traumatol 1991;34:397-400. [Google Scholar]

- 18. Baba H, Imura S, Tomita K. Achondroplasia with spinal cord or cauda equina symptoms: Report of three cases. Orthop Surg 1992;43:47-52. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lutter LD, Longstein JE, Winter RB, Langer LO. Anatomy of the achondroplastic lumbar canal. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;126:139-142. [Google Scholar]

- 20. Suzuki K, Kanamori M, Nobukiyo M. Ossification of the thoracic ligamentum flavum in an achondroplastic patient: A case report. J Orthop Surg (Hong Kong) 2008;16:392-5. [Google Scholar]

- 21. Liao JC, Chen WJ, Lai PL, Chen LH. Surgical treatment of achondroplasia with thoracolumbar kyphosis and spinal stenosis-a case report. Acta Orthop 2006;77:541-44. [Google Scholar]

- 22. Saito K, Miyakoshi N, Hongo M, Kasukawa Y, Ishikawa Y, Shimada Y. Congenital lumbar spinal stenosis with ossification of the ligamentum flavum in achondroplasia: A case report. J Med Case Rep 2014;8:88. [Google Scholar]

- 23. Chakraborty T, Sharma D, Goyal A, Madan VS. A rare case of ossification of ligamentum flavum presenting as dorsal myelopathy in achondroplasia. J Neurol Stroke 2017;7:11-2. [Google Scholar]

- 24. Abu Al-Rub Z, Lineham B, Hashim Z, Stephenson J, Arnold L, Campbell J, et al. Surgical treatment of spinal stenosis in achondroplasia: Literature review comparing results in adults and paediatrics. J Clin Orthop Trauma 2021;23:101672. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Agabegi SS, Antekeier DP, Crawford AH, Crone KR. Postlaminectomy kyphosis in an achondroplastic adolescent treated for spinal stenosis. Orthopedics 2008;31:168. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Ain MC, Elmaci I, Hurko O, Clatterbuck RE, Lee RR, Rigamonti D. Reoperation for spinal restenosis in achondroplasia. J Spinal Disord. 2000;13:168–73. [Google Scholar]

- 27. Pyeritz R.E., Sack G.H., Udvarhelyi G.B., Opitz J.M., Reynolds J.F. Thoracolumbosacral laminectomy in achondroplasia: long-term results in 22 patients. Am J Med Genet. 1987 Oct;28(2):433–444. doi: 10.1002/ajmg.1320280221. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Sun J, Zhang C, Ning G, Li Y, Li Y, Wang P, et al. Surgical strategies for ossified ligamentum flavum associated with dural ossification in thoracic spinal stenosis. J Clin Neurosci 2014;21:2102-6. [Google Scholar]