India is experiencing rapid growth in joint replacement surgery, yet its registry coverage remains limited. Strengthening the Indian Joint Registry into a nationwide, mandatory, surgeon-led, and digitally integrated system – supported by government policy, sustainable funding, and industry collaboration – is crucial. Integration of robotic datasets, corporate accountability, regular audits, and global partnerships will transform the registry into a reliable platform for early implant surveillance, quality benchmarking, and evidence-based improvements in arthroplasty care.

Dr. Kunal Aneja, Max Super Speciality Hospital, Shalimar Bagh, New Delhi, India and Naveda Healthcare Centres, New Delhi, India. E-mail: drkunalaneja@gmail.com

Longer life expectancy, the rising burden of osteoarthritis, increasing obesity, and a growing desire among older adults to maintain active lifestyles have all contributed to a significant surge in joint-related health needs; as a result, the demand for total hip and knee arthroplasties is expected to increase substantially by 2026 [1,2]. A recent survey estimated that roughly 200,000 knee replacements were performed in 2020 alone, reflecting rapid growth driven by demographic and lifestyle changes [3]. Despite the expanding volume of total hip and knee arthroplasties, India still lacks a centralized, fully operational National Joint Registry (NJR). In many countries, NJRs are a vital part of orthopedic practice, helping surgeons monitor implant outcomes, improve techniques, and guide health policy [4]. In the Indian context, establishing an NJR is no longer optional; it has become an urgent necessity. For example, the 2010 recall of a faulty metal-on-metal hip implant (DePuy ASR) highlighted the consequences of not having a registry: of the 4,700 ASR implants done in India, only 882 patients could be traced for remedial action [2]. This incident highlighted serious shortcomings in India’s medical device regulations, such as delayed action on international recalls and the lack of systems to effectively trace affected patients. A robust NJR would have enabled health authorities to identify all affected patients, thereby mitigating harm promptly. This editorial discusses the global success of joint registries, reviews India’s progress so far, and outlines strategic imperatives to develop a comprehensive Indian Joint Registry (IJR).

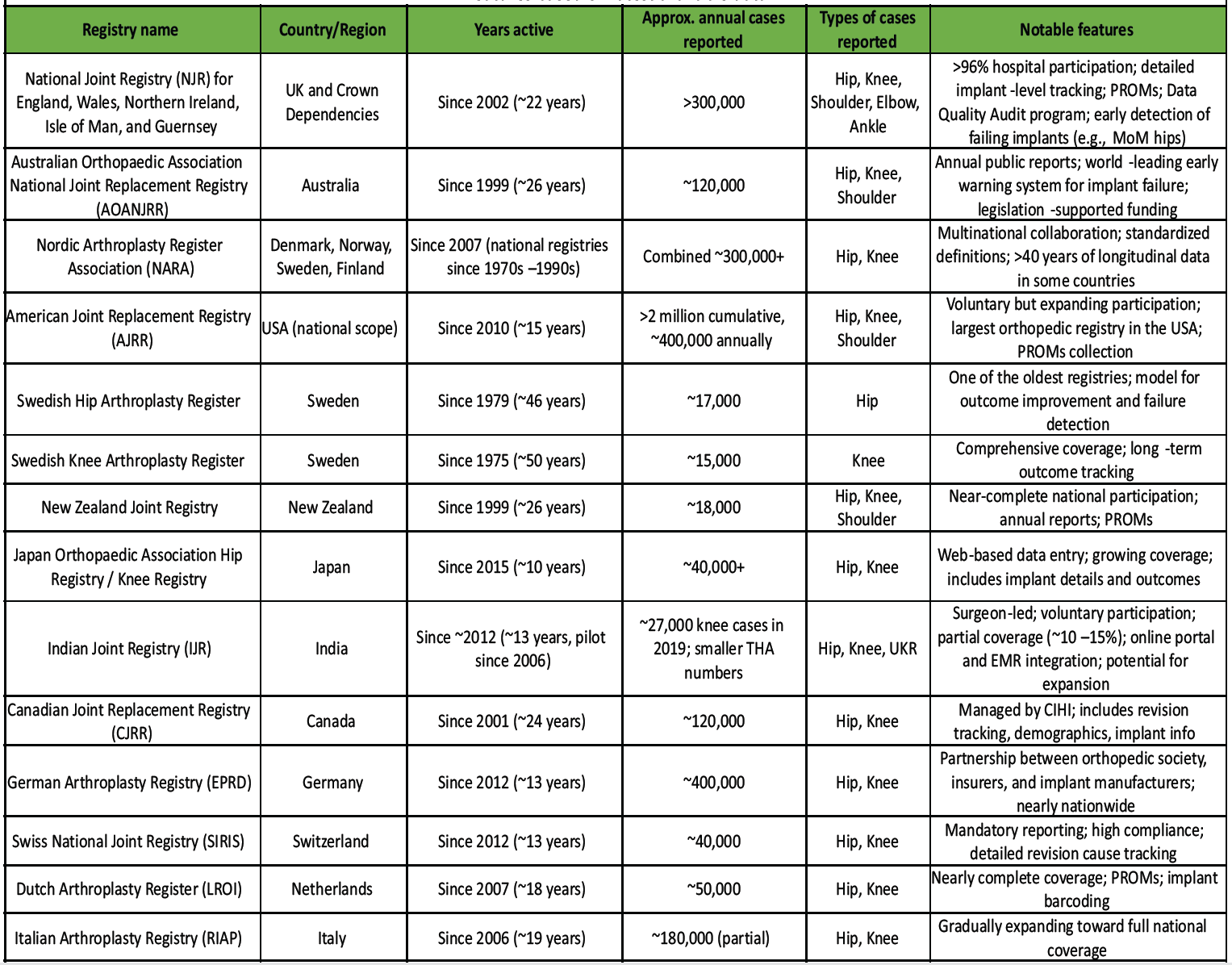

Around the world, national joint registries have demonstrated immense value in improving orthopedic outcomes and patient safety (Table 1).

Table 1: Summary of major national and regional joint replacement registries, showing location, years active, annual case volume, procedure types, and key features based on latest available data

The United Kingdom’s NJR, established in 2002, now has over 96% of hospitals participating and covers more than 2 million procedures [5]. Its large-scale data enabled early identification of underperforming implants – notably the metal-on-metal hip replacements that showed a re-revision rate above 6% within 5 years, prompting regulatory actions and a global alert on these devices [6]. Likewise, the Australian Orthopaedic Association National Joint Replacement Registry (AOANJRR) detected high-failure implant designs and facilitated their withdrawal, leading to a 25.8% reduction in revision surgeries nationwide [7]. Countries with well-organized registries have not only improved patient outcomes but also reduced healthcare costs. For example, analyses in the United States estimated that using registry data to refine practices saved around $2 billion in hip replacement expenditures by averting failures and revisions [8]. In Scandinavia, the national registry, The Nordic Arthroplasty Register Association (NARA) for hip and knee replacement has been in place for decades and is considered a global benchmark, has shown that systematic data collection over time correlates with lower complication and revision rates [9]. These registries not only gather data but also actively empower surgeons with real-world evidence on implant longevity, complication trends, and best practices [2]. The collective global experience makes it clear that a national registry is indispensable for delivering high-quality, evidence-based care for joint replacement. India can draw important lessons from these models as it strives to implement its NJR.

Early initiatives

India’s journey toward a joint registry began in 2006, when the Indian Society of Hip and Knee Surgeons (ISHKS) launched a preliminary registry for hip and knee arthroplasties [10]. That early effort provided a proof of concept, capturing tens of thousands of cases over the next few years. By 2012, the registry had recorded over 34,000 total knee arthroplasties (TKAs) and 3,600 total hip arthroplasties (THAs), yielding insights into patient demographics and implant usage (e.g., mean age ~64 for TKA, with 75% of TKA patients being women) [10].

The IJR

Building on the ISHKS pilot, a more comprehensive IJR was later established to systematically collect data on joint replacement surgeries across the country [2,10]. The IJR is designed as a national database to track every hip or knee replacement case, including patient demographics, diagnosis, surgical details, implant specifics, and outcomes. Data submission is done by participating surgeons and hospitals either through a secure online portal or through integration with hospital electronic record systems. All patient information is anonymized to ensure privacy and confidentiality [11]. This structure allows the registry to function as a real-time surveillance and quality improvement tool – monitoring implant performance and supporting research to identify best practices in arthroplasty. Importantly, the IJR was initiated and is maintained by professional bodies (ISHKS and the Indian Orthopaedic Association), reflecting a surgeon-led approach in its governance and priorities.

Current status and growth

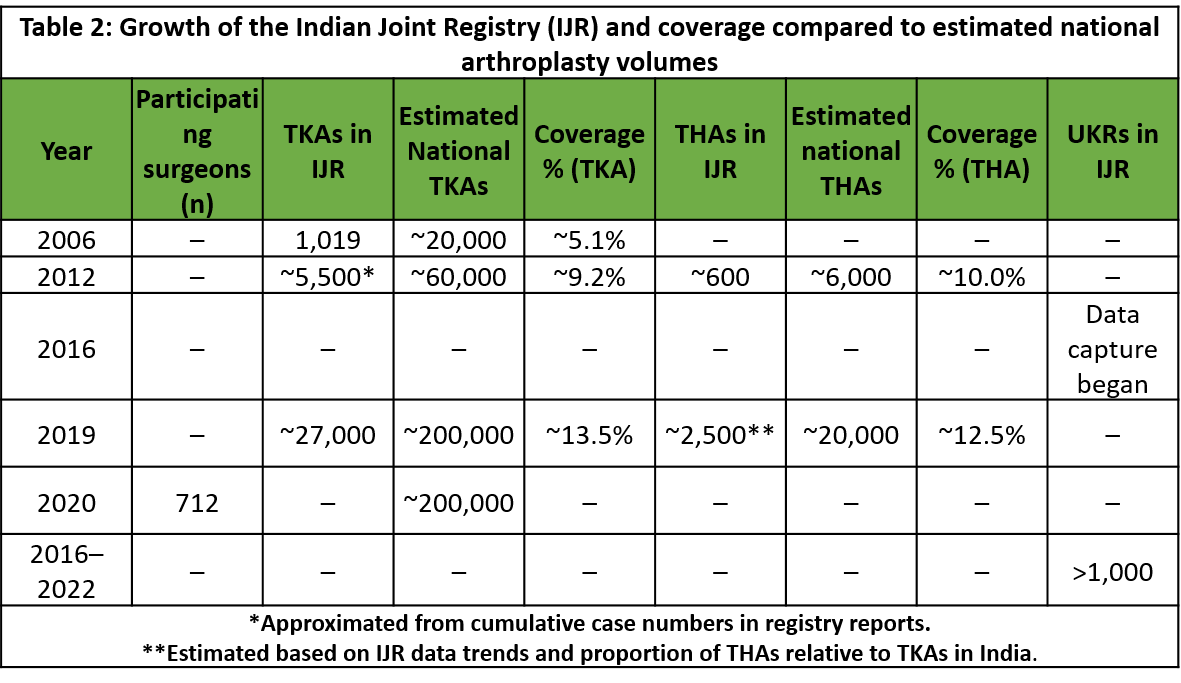

Participation in the IJR has grown steadily, though it remains voluntary. By June 2020, the registry had enrolled data from 712 orthopedic surgeons nationwide [2]. The number of procedures being captured has increased dramatically: 1,019 knee replacements were reported in 2006, whereas about 27,000 knee replacements entered into the registry in 2019 [2]. This exponential rise mirrors the overall growth of arthroplasty in India and indicates improving engagement with the registry. The IJR’s dataset has expanded to include not only primary THAs and TKAs but also more specialized procedures, for example, between 2016 and 2022, over 1,000 unicompartmental knee replacements (UKRs) were documented, reflecting the gradual adoption of partial knee replacement techniques in the country [12]. Such data help identify emerging trends and outcomes for newer procedures in the Indian population (Table 2).

Despite these advances, the IJR is still far from reaching its full potential. Coverage of cases is incomplete – many surgeries across India are never entered into the registry. To put this in perspective, an estimated ~200,000 knee arthroplasties were performed in India in 2020, whereas only ~27,000 knee cases from 2019 were recorded in the registry [2,13]. In other words, likely only a small fraction of total procedures is being captured. In addition, the registry’s participation is largely concentrated among certain hospitals and surgeons who volunteer data, which may introduce reporting bias. Nonetheless, the IJR stands out in the region: a recent review identified six national arthroplasty registries across Asia, but only three countries – India, Japan, and Pakistan have fully established registries with official websites and published annual reports for public data sharing [14]. This highlights both the progress India has made and the gap that remains. The challenge now is to transition the IJR from a voluntary, limited initiative to a truly nationwide, mandatory registry that can capture all joint replacement surgeries in India. For a registry to generate meaningful and valid data, participation of at least 90% of arthroplasty surgeons is essential. Current voluntary reporting falls well short of this standard, limiting the registry’s reliability and impact.

Despite these advances, the IJR is still far from reaching its full potential. Coverage of cases is incomplete – many surgeries across India are never entered into the registry. To put this in perspective, an estimated ~200,000 knee arthroplasties were performed in India in 2020, whereas only ~27,000 knee cases from 2019 were recorded in the registry [2,13]. In other words, likely only a small fraction of total procedures is being captured. In addition, the registry’s participation is largely concentrated among certain hospitals and surgeons who volunteer data, which may introduce reporting bias. Nonetheless, the IJR stands out in the region: a recent review identified six national arthroplasty registries across Asia, but only three countries – India, Japan, and Pakistan have fully established registries with official websites and published annual reports for public data sharing [14]. This highlights both the progress India has made and the gap that remains. The challenge now is to transition the IJR from a voluntary, limited initiative to a truly nationwide, mandatory registry that can capture all joint replacement surgeries in India. For a registry to generate meaningful and valid data, participation of at least 90% of arthroplasty surgeons is essential. Current voluntary reporting falls well short of this standard, limiting the registry’s reliability and impact.

Establishing an effective, sustainable NJR in India will require concerted action on multiple fronts. The following strategic imperatives should be prioritized:

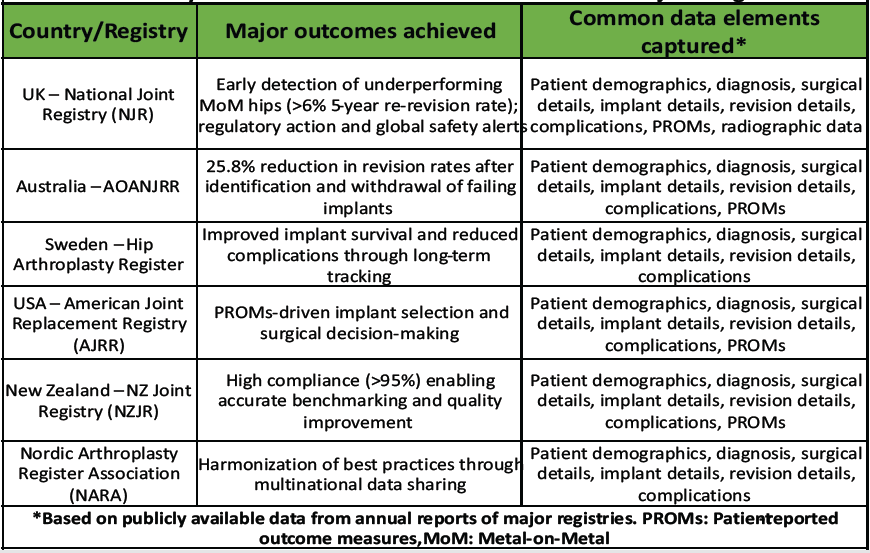

- Mandatory Nationwide Participation: Broaden registry coverage by making data submission compulsory. Voluntary participation has yielded suboptimal data capture – many centers still opt out, leaving significant gaps [15]. To address this, reporting every joint replacement to the IJR should become standard protocol across all hospitals performing these surgeries. Tying registry participation to hospital accreditation, surgeon credentialing, or insurance reimbursement can powerfully incentivize compliance. For instance, including registry data reporting as a criterion for NABH hospital accreditation or as a requirement by insurance providers (for procedure coverage) would ensure that centers routinely contribute data. International experience shows that near-universal compliance is achievable; the UK’s NJR reached 96% coverage after implementing systematic enrollment and data quality audits (DQAs). India must likewise move from a voluntary system to a mandated one to capture a truly national dataset (Table 3).

Table 3: Key benefits achieved in countries with mature joint registries

- Professional Leadership and Governance: The IJR should continue to be managed by orthopedic professional bodies such as ISHKS and the Indian Orthopaedic Association, which ensure that it reflects clinical priorities and maintains the trust of surgeons [2]. A surgeon-led governance model can better promote buy-in, as clinicians are more likely to participate when they see the registry is run for and by their peers [14]. At the same time, strong support from health authorities is needed – for policy backing and funding. A joint governance council could be formed, comprising leaders from ISHKS/IOA and representatives of the Ministry of Health, to institutionalize the registry within national healthcare plans. This collaboration can help align the IJR with public health objectives and possibly make registry reporting a legally endorsed requirement (similar to notifiable diseases or device tracking programs) [2,14].

- Digital Infrastructure and Data Quality Assurance: A user-friendly digital infrastructure is crucial to facilitate seamless data entry without overburdening surgeons. The registry should integrate with hospital information systems and electronic medical record platforms so that data can be uploaded with minimal manual effort. Modern registries are increasingly adopting semi-automated data capture methods – for example, pulling relevant data from operative notes or implant labels through barcode scanning – to improve efficiency.

The IJR should explore such innovations, which have been piloted in multi-institutional networks abroad, to streamline data collection. Ensuring data quality is equally important: the information submitted must be complete and accurate. Robust quality assurance mechanisms need to be implemented, including automatic error checks, periodic audits, and validation studies [16]. The UK NJR provides a compelling model through its DQA program, which validates registry entries against hospital records – such as Patient Administration Systems – to identify missing cases and correct discrepancies. The DQA program is a notable example of how active validation improved data completeness and compliance. In addition, evidence from a high-volume orthopedic center revealed that local revision data review identified discrepancies of 20–25%, underscoring the need for multidisciplinary case validation [17]. India could institute regular audits comparing registry entries against hospital records to identify under-reporting or inconsistencies. Establishing dedicated data management teams – especially in high-volume centers – can greatly enhance data quality. These teams would train clinical staff on data entry protocols, follow up on missing information, and ensure the timely submission of cases. Such measures have a proven impact: for instance, national surgical audit programs in Australia not only improved data reporting but also were associated with significant outcome gains (a 30% reduction in surgical mortality was observed in Western Australia after implementing a statewide audit and feedback system) [18]. By combining state-of-the-art digital tools with diligent quality control, the IJR can build a reliable repository of information that clinicians and researchers trust.

Sustainable funding and policy support

Financial sustainability is a major concern for any national registry. Regular funding is needed for IT infrastructure, personnel (data managers, analysts), training, and annual report generation. The government, possibly in partnership with industry stakeholders and healthcare institutions, should allocate dedicated funds for the IJR’s operations. This could be done by including the registry in national health budgets or quality improvement programs. Public-private partnerships might also be explored, wherein implant manufacturers or insurance companies contribute funding as part of their commitment to patient safety (with appropriate firewalls to prevent any conflict of interest in data handling). Policymakers must recognize the NJR as a public health asset: by preventing failures and revisions, the registry will save costs for both patients and the healthcare system [14]. Advocating for the IJR’s importance is an immediate priority – orthopedic leaders should actively engage with health ministry officials to ensure support. Indeed, a recent call to action emphasizes that surgeons and professional bodies need to lobby for making the IJR a national priority and securing sustainable funding for it. As a first step, the registry could be linked with existing government initiatives such as Ayushman Bharat or state insurance schemes, thereby embedding it within the reimbursement process. Over time, formal legislation could mandate registry reporting similar to the models used in other countries where device tracking is legally required. For instance, Australia introduced the Health Insurance (National Joint Replacement Register Levy) Bill 2009, which effectively supported the National Joint Replacement Registry through government-level recognition and financial commitment to tracking hip and knee arthroplasty outcomes nationwide [18]. With assured funding and policy backing, the IJR can evolve into a sustained national program instead of remaining a short-term initiative.

Role of industry partners and emerging technologies in registry strengthening

A persistent challenge for the IJR remains incomplete coverage, with only a small fraction of national arthroplasty procedures captured. Addressing this gap requires coordinated efforts not only from surgeons and policymakers but also from industry partners who hold a leadership position in the Indian arthroplasty space. Implant companies such as Zimmer Biomet, Stryker, Smith and Nephew, Johnson and Johnson (DePuy Synthes), Meril, and Biorad are uniquely placed to support registry growth. Their company sales representatives and operating theater assistants, who are routinely present during surgeries to handle implant boxes, can be engaged in assisting with real-time data capture. These representatives could ensure that implant details and demographic information are accurately entered into the registry at the point of care. Making such participation a compulsory internal compliance requirement would standardize reporting and substantially reduce under-reporting.

In addition to manual data entry support, the rapid adoption of robotic-assisted arthroplasty in India presents another opportunity to enrich registry data. Robotic systems generate comprehensive datasets, including computed tomography-based pre-operative planning, intraoperative balancing, and alignment parameters. Currently, much of this information remains siloed within proprietary platforms. Linking robotic datasets to registry entries would allow unprecedented insight into the impact of different alignment strategies and balancing techniques on long-term outcomes. Such integration would not only enhance the robustness of registry data but also support cutting-edge research on the real-world effectiveness of emerging technologies.

Among all stakeholders, Meril stands out as a market leader in Indian arthroplasty, with both an extensive implant portfolio and the indigenous MISSO robotic system. Its leadership position confers a responsibility to drive registry compliance and innovation. Meril is well-positioned to mandate registry-linked reporting for its implants and robotic cases, fund data management infrastructure under corporate social responsibility initiatives, and work collaboratively with professional societies such as ISHKS and IOA to establish uniform reporting protocols. At the same time, multinational companies such as Zimmer Biomet, Stryker, Smith and Nephew and Johnson and Johnson (DePuy Synthes), must also share this responsibility, ensuring registry compliance as part of their corporate commitment to safety and quality [19]. By actively enabling registry data capture and integrating robotic outputs, these companies – alongside Meril and other domestic leaders like Biorad – can set a benchmark for corporate accountability, positioning themselves as key partners in elevating the quality, transparency, and global recognition of Indian arthroplasty outcomes.

Feedback, transparency, and collaboration

For the registry to drive change, participants must receive meaningful feedback. The IJR should produce annual reports and surgeon-level dashboards that anonymously compare outcomes across centers and regions. Such benchmarking allows surgeons and hospitals to identify areas for improvement by seeing how their results stack up against national averages or against high-performing centers. Transparency in outcomes (while protecting individual patient and surgeon identity) can foster a healthy competition to improve. In addition, the registry data should be accessible to researchers for analysis under appropriate protocols, spurring evidence-based innovations. International collaboration is also invaluable: partnering with established registries (like those in the UK, Australia, and Sweden) can provide technical guidance on best practices. India could join collaborative analyses or registry networks, as Scandinavia did with NARA, to compare data and gain insights. Adopting globally accepted definitions, data fields, and analytic methods will improve the IJR’s credibility and utility. There is also scope to incorporate patient-reported outcome measures into the registry, an area where some advanced registries have considerable experience. By aligning with international standards, the Indian registry can ensure its data are interoperable and contribute to multi-country studies (e.g., identifying issues with specific implant brands worldwide) [2]. Finally, continuous education based on registry findings is key: the IJR leadership should regularly disseminate findings through workshops, clinical meetings, and publications so that front-line surgeons appreciate the registry’s value. When surgeons see tangible benefits – such as identification of a problematic implant that they can then avoid, or validation of a surgical technique that improves outcomes – it creates a positive feedback cycle reinforcing participation. In summary, by providing feedback and embracing collaboration, the registry will not only collect data but also actively use it to elevate the standard of joint replacement care in India.

The establishment of a comprehensive NJR in India is an idea whose time has come. It is not merely an academic exercise but a practical necessity to improve patient care. A well-implemented NJR will enable the tracking of implant performance, facilitate early warning of failing devices, improve patient safety, and reduce the burden of costly revision surgeries. Evidence from successful registries around the world consistently demonstrates the value of national data systems in lowering revision rates, identifying underperforming implants, and guiding policy reforms in arthroplasty. To translate this vision into reality in India, all stakeholders must collaborate and commit. Orthopedic surgeons, through ISHKS and IOA, need to champion the cause and lead by example in contributing data. Hospitals must integrate registry reporting into their workflow as a quality mandate. Policymakers and government agencies should provide the necessary mandates, funding, and infrastructural support to scale up the IJR. Making data reporting mandatory – supported by user-friendly digital systems and strong institutional backing – will pave the way for a reliable, transparent, and effective registry. With collective effort, India can develop an NJR that matches global best practices and becomes a model for other surgical fields.

A robust joint replacement registry like the IJR is essential for improving patient outcomes, tracking implant performance, and guiding national arthroplasty practices. While India has made meaningful progress, the registry must transition from a voluntary initiative to a nationwide, mandated system. Surgeon-led governance, mandatory data reporting, governmental support, regular audits and data quality checks, and global collaboration are key to its success. Ultimately, a well-supported IJR can serve as a cornerstone for evidence-based, high-quality joint care across India.

References

- 1. Available from: https://www.business-standard.com/content/press-releases-ani/robotic-joint-replacement-surgeries-how-health-insurance-can-partner-in-expanding-access-to-advanced-orthopaedic-care-for-indian-patients-125070301313_1.html. [Last accessed on 2025 Jul 01]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Vaidya SV, Jogani AD, Pachore JA, Armstrong R, Vaidya CS. India joining the world of hip and knee registries: Present status-a leap forward. Indian J Orthop 2021;55 Supp1 1:46-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Available from: https://www.market-scope.com/pages/reports/orthopedic?page=1 [Last accessed on 2025 Jul 01]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Hoskins W, Bingham R, Vince KG. A systematic review of data collection by national joint replacement registries: What opportunities exist for enhanced data collection and analysis? JBJS Rev 2023;11:e23.00062. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Matharu GS, Judge A, Pandit HG, Murray DW. Which factors influence the rate of failure following metal-on-metal hip arthroplasty revision surgery performed for adverse reactions to metal debris? An analysis from the National Joint Registry for England and Wales. Bone Joint J 2017;99-B:1020-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Furnes O, Paxton E, Cafri G, Graves S, Bordini B, Comfort T, et al. Distributed analysis of hip implants using six national and regional registries: Comparing metal-on-metal with metal-on-highly cross-linked polyethylene bearings in cementless total hip arthroplasty in young patients. J Bone Joint Surg 2014;96 Suppl 1:25-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Luo R, Brekke A, Noble PC. The financial impact of joint registries in identifying poorly performing implants. J Arthroplasty 2012;27 8 Suppl:66-71.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Larsson S, Lawyer P, Garellick G, Lindahl B, Lundström M. Use of 13 disease registries in 5 countries demonstrates the potential to use outcome data to improve health Care’s value. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:220-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Havelin LI, Robertsson O, Fenstad AM, Overgaard S, Garellick G, Furnes O. A Scandinavian experience of register collaboration: The Nordic arthroplasty register association (NARA). J Bone Joint Surg Am 2011;93 Suppl 3:13-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Pachore JA, Vaidya SV, Thakkar CJ, Bhalodia HK, Wakankar HM. ISHKS joint registry: A preliminary report. Indian J Orthop 2013;47:505-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Pandian H. A perspective of growth of unicompartmental knee replacement in India-registry data and global trends. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:179-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Available from: https://axiommrc.com/product/1735-joint-replacement-market-report [Last accessed on 2025 Jul 01]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Shum BC, Lau LC, Cheung JP, Choi SW. Current status of Asian joint registries: A review. EFORT Open Rev 2025;10:250-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Barsoum WK, Higuera CA, Tellez A, Klika AK, Brooks PJ, Patel PD. Design, implementation, and comparison of methods for collecting implant registry data at different hospital types. J Arthroplasty 2012;27:842-50.e1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Paxton EW, Inacio MC, Khatod M, Yue EJ, Namba RS. Kaiser Permanente national total joint replacement registry: Aligning operations with information technology. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2646-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Afzal I, Radha S, Smoljanović T, Stafford GH, Twyman R, Field RE. Validation of revision data for total hip and knee replacements undertaken at a high volume orthopaedic centre against data held on the National Joint Registry. J Orthop Surg 2019;14:318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Raju RS, Maddern GJ. Lessons learned from national surgical audits. Br J Surg 2014;101:1485-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Parliament of Australia. Health Insurance (National Joint Replacement Register Levy) Bill 2009; 2009. Available from: https://www.aph.gov.au/parliamentary_business/committees/senate/community_affairs/completed_inquiries/2008-10/private_hth_nat_joint_replace_reg_09/report/c01 [Last accessed on 2025 Aug 01]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Aneja K, Machaiah PK, Shyam A. Training of a joint replacement surgeon in India: Past, present, and future perspectives. J Orthop Case Rep 2025;15:4-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]