Dorsal claviculectomy is a novel treatment for brachial plexus stretch injury following scapulothoracic fusion; early diagnosis and strategic interventions enhance patient outcomes.

Dr. Yamaan S Saadeh, Department of Neurosurgery, University of Michigan, Taubman Health Care Center, Ann Arbor, USA. E-mail: yamaans@med.umich.edu

Introduction: Scapulothoracic fusion is a procedure used to treat severe cases of scapular instability, most commonly due to facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD). Patients who undergo scapulothoracic fusion surgery are at risk for neurovascular complications such as brachial plexus (BP) injury.

Case Report: A 35-year-old right-hand-dominant female with FSHD who underwent scapulothoracic fusion which was complicated by a BP injury which did not improve with reoperation for scapular repositioning.

Conclusion: We performed a novel treatment of dorsal claviculectomy, after which the patient experienced near complete recovery of her BP injury. Dorsal claviculectomy can be considered as a treatment option for BP injury following scapulothoracic fusion, to relieve BP stretch and promote neural recovery.

Keywords: Brachial plexus injury, dorsal claviculectomy, facioscapulohumeral dystrophy, neurovascular complications, scapular stabilization, scapulothoracic fusion, winged scapula.

Scapulothoracic fusion is a procedure used to stabilize the scapula by fixating it to the chest wall. This procedure is used in conditions of severe scapular dysfunction, such as traumatic scapulothoracic dissociation, winged scapula from conditions such as facioscapulohumeral dystrophy (FSHD), and congenital deformities such as Sprengel’s deformity, among other indications [1]. Scapulothoracic fusion is often a last resort, after patients have exhausted more conservative measures, such as physical therapy, bracing, injections, or tendon transfers [2]. Scapulothoracic fusion carries a number of risks, including pneumothorax, nonunion, rib fractures, and brachial plexus (BP) injuries [3]. BP injuries have been reported in 2.5–8.3% of cases of scapulothoracic fusion for FSHD [3,4,5].

The goal of scapulothoracic fusion is to improve shoulder stability or correct a deformity (depending on the indication) by fixating the scapula to the chest wall. The procedure carries certain risks, including failure to improve symptoms, failure to fuse, reduced shoulder mobility, pneumothorax, cosmetic issues, and neurovascular injury including BP injury [3]. We present a case report of a patient treated with pan BP injury following scapulothoracic fusion. The injury failed to improve with repositioning of the scapula and was treated using a novel approach: Dorsal claviculectomy. We also provide a review of the literature on BP injuries related to scapulothoracic fusion, as well as other previously described management strategies.

A 35-year-old right-hand-dominant female presented as a new patient to our emergency department with a history of FSHD, with left scapular winging and progressive difficulty with shoulder abduction and forward flexion. She had undergone a long thoracic nerve decompression 2 years ago and a pectoralis major transfer 18 months prior, both at other hospitals, neither of which provided any significant benefit. These previous surgeries were complicated by postoperative venous thromboembolic disease.

She also underwent a scapulothoracic fusion at another hospital, 4 weeks before presentation, where the scapula was fixated to ribs three, four, five, and six. Intraoperative monitoring was utilized, and a decrease in somatosensory evoked potential to the left upper extremity (LUE) was noted at the beginning of the case, which remained stable and did not worsen. Postoperatively, she presented with a complete loss of motor function in her LUE, severe burning pain, as well as a near-complete loss of sensation. Bilateral radial pulses were noted to be intact. A computed tomography (CT) of venogram demonstrated large thrombus in the left subclavian vein and narrowing of the costoclavicular portion of the thoracic outlet. The patient was returned to the operating room 2 days postoperatively for repositioning of the scapula on the chest wall. The scapula was translated cranially and fixated to ribs two, three, four, and five to reduce compression within the thoracic outlet. Postoperatively, the patient had a persistent LUE flail arm with no improvement. Therapeutic anticoagulation was prescribed for the treatment of LUE deep vein thrombosis (LUE DVT).

Four weeks postoperatively, the patient presented to our institution for progressive swelling in the LUE and neck. CT angiography (CTA) imaging demonstrated an increase in the amount of DVT in the subclavian vein and new DVT within the left internal jugular vein. The patient had no improvement in the LUE flail arm. Consequently, the patient was admitted, and a heparin drip was initiated.

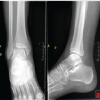

Further diagnostic studies were performed. Nerve conduction studies showed the absence of median, ulnar, and radial sensory responses, and decreased amplitude of median and ulnar motor responses. An electromyography study showed profuse active denervation with no motor units throughout the muscles of the entire LUE (Table 1).

Table 1: Patient’s EMG results

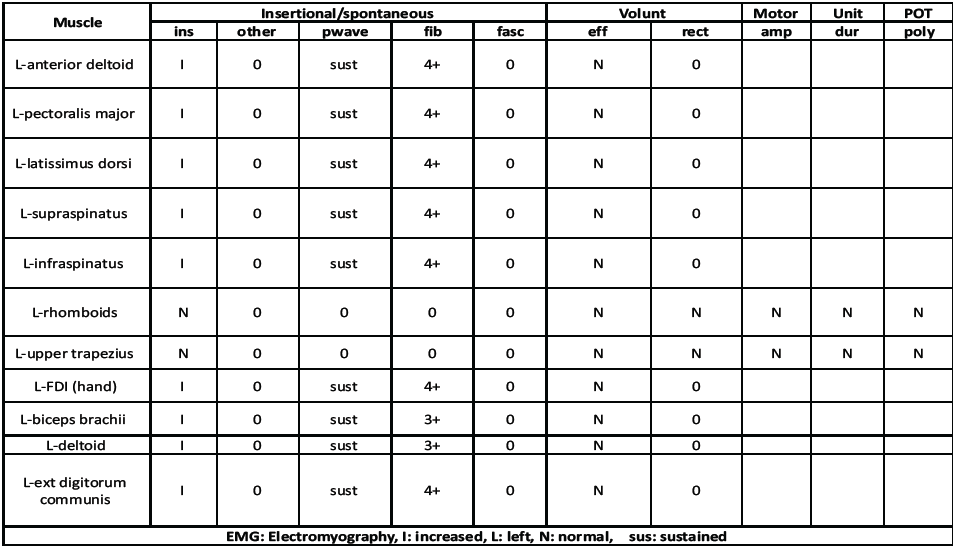

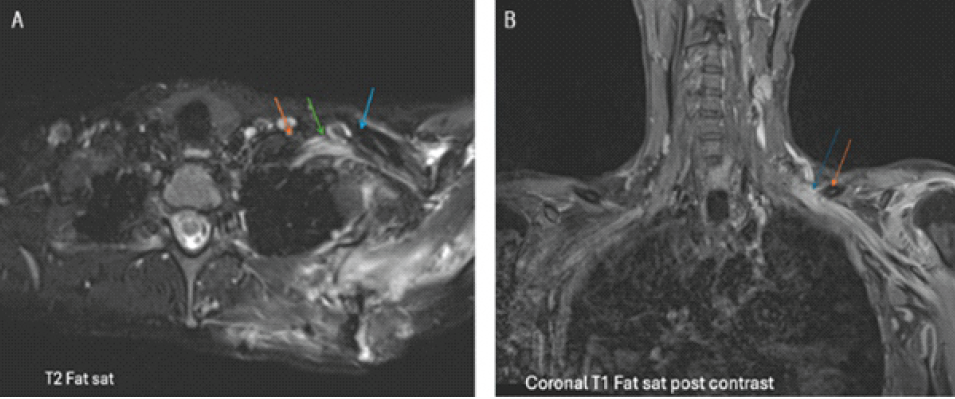

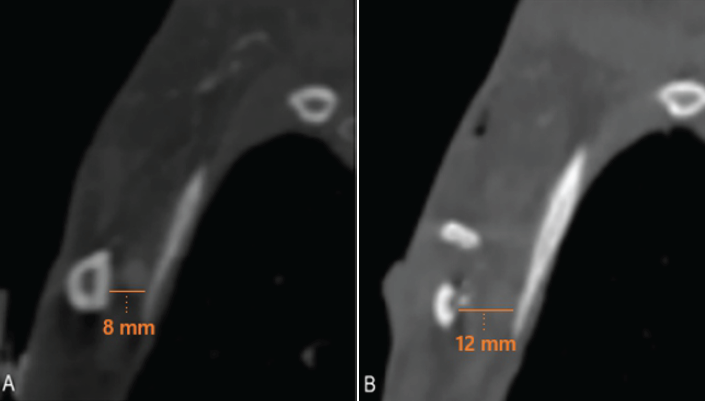

Imaging with CTA of the chest and magnetic resonance imaging of the left BP demonstrated relative narrowing of the costoclavicular space to 8 mm (Fig. 1a) and diffuse edema of the BP (Fig. 1b), most prominent proximal to the costoclavicular space. Additionally, the scapula on the left side was significantly medialized compared to the right side (Fig. 1c). Typically, the costoclavicular interval measures 12 mm [4].

Figure 1: Computed tomography angiography imaging (a) of the chest showing the normal costoclavicular interval on the unaffected right side (15 mm), (b) narrowing on the affected left side (8 mm), and (c) medialization of the left scapula noted relative to the right side, as well as narrowing of the costoclavicular interval on the left side.

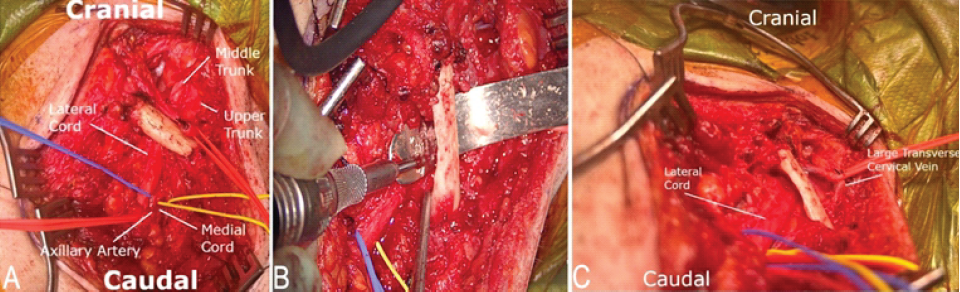

Given the clinical, electrophysiological diagnostics, and imaging findings, severe BP stretch resulting in LUE flail arm was suspected. Risks and benefits of first rib resection were discussed, and the patient wished to proceed. Intraoperatively, combined supraclavicular and infraclavicular exposure of the BP was performed for full assessment. The BP was observed to be pushed downward by the clavicle, and there was significant traction on the plexus, as well as medial and downward tension (Fig. 2a and b).

Figure 2: (a) Axial T2FS: Edematous and posteriorly angled left brachial plexus nerves (green arrow) coursing distally, inferior to the clavicle (blue arrow). Lateral interscalene area (orange arrow). (b) Coronal T1FS: Enhancement of the left brachial plexus (blue arrow), extending from proximal to the clavicle (orange arrow) distally.

It was apparent that the first rib resection would not relieve this traction. Complete claviculectomy was considered but felt to be nonoptimal due to cosmetic considerations, as well as concern for causing shoulder instability. The surgical team opted for a dorsal claviculectomy, in which a high-speed drill was used to resect the dorsal half of the clavicle (Fig. 3 a, b, c). Thin malleable retractors were used to protect and gently retract the BP to prevent injury with the drill and to allow working room for the drill (Fig. 3b).

Figure 3: (a) Exposure of the supraclavicular and infraclavicular brachial plexus, with downward stretch of the brachial plexus by the clavicle. (b) High-speed drill used to perform dorsal claviculectomy, with a malleable retractor protecting the retroclavicular neurovascular elements. (c) Relief of the brachial plexus downward stretch following dorsal claviculectomy.

The dorsal cortical rim of the clavicle was removed, as well as most of the medullary bone. This resulted in the removal of approximately 50–60% of the clavicle cross-sectional area in the region where the BP crossed. This procedure was chosen to reduce the amount of traction on the BP and relieve the stretch injury, while avoiding the morbidity of a full claviculectomy. Postoperative imaging showed the extent of the dorsal claviculectomy, especially in comparison to preoperative imaging (Fig. 4a and b). A heparin drip was resumed shortly after surgery.

Postoperatively, the patient remained in a sling at all times for 2 additional weeks, until she completed a total of 6 weeks of postoperative sling immobilization following her initial scapulothoracic fusion. Following this, she wore a sling only when out of bed to support her arms weight as her BP injury recovered.

Postoperatively, the patient remained in a sling at all times for 2 additional weeks, until she completed a total of 6 weeks of postoperative sling immobilization following her initial scapulothoracic fusion. Following this, she wore a sling only when out of bed to support her arms weight as her BP injury recovered.

Two days postoperatively, the patient began to activate finger flexion. At 4 weeks postoperatively, she could still activate finger flexion as well as finger extension and abduction. She initiated structured physical therapy at this time 2–3 times weekly to help improve range of motion and promote movement and recovery. At 4 months postoperatively, she showed greater than antigravity strength in finger flexion extension, wrist flexion, extension, and elbow extension but had weak activation of elbow flexion and shoulder abduction. At 6 months postoperatively, she had Medical Research Council (MCR) four/five strength throughout her entire LUE. At 12 months postoperatively, she had full strength in shoulder and elbow function, and a MCR strength of four plus/five wrist and finger function, with continued improvement.

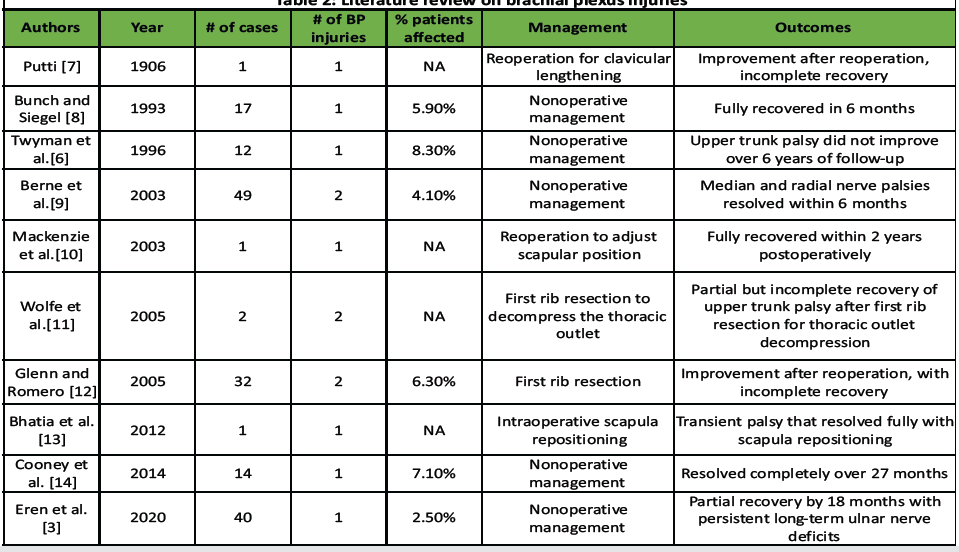

Scapulothoracic fusion is an established treatment for scapular stabilization in cases of instability, such as FSHD, among other indications. A known complication of this procedure is BP injury. Previously described strategies for this complication include reoperation to adjust the scapula’s position on the chest wall, first rib resection, and watchful waiting. This case report is the first, to our knowledge, to describe the use of dorsal claviculectomy for the treatment of BP stretch injury. BP injuries have been reported to occur at a rate of 2.5–8.3% after scapulothoracic fusion for FSHD [3,5,6]. From 1906 to the present, multiple reports have detailed BP injuries from scapulothoracic fusion, along with their treatments and outcomes [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14], as summarized in Table 2.

Table 2: Literature review on brachial plexus injuries

Consensus on the exact mechanism of BP injury in patients with scapulothoracic fusion does not exist. The predominant theory is that the BP is directly compressed between the first rib and clavicle. As the scapula is translated inferiorly and medially, the clavicle is also pulled toward the first rib through the acromioclavicular joint, causing narrowing of the costoclavicular space of the thoracic outlet. However, another possibility, as reported in our case, is the downward and medial stretch of the BP by the clavicle as the scapula is mobilized. Surgical treatments described in the literature have focused on (1) superior and lateral repositioning of the scapula to expand the costoclavicular space, as well as (2) first rib resection to further open the space. Both treatment strategies would be effective for a compressive mechanism of action. However, if the mechanism of action is due to a stretch injury of the BP by the clavicle, only surgical repositioning of the scapula, or clavicular osteotomy or resection, could improve the stretch. Rib resection would not be expected to have a therapeutic effect on the downward and medial stretch by the clavicle. With dorsal or partial claviculectomy, there is a theoretically increased risk of clavicle fracture given the removal of a large portion of the clavicular structure. For this patient, this risk was ameliorated by her scapulothoracic fusion, which limited the movement of the clavicle. Additionally, numerous studies on partial claviculectomies within the oncology literature report high functional outcomes without any reported clavicle fractures [15]. Procedures focused on the clavicle have been described for scapulothoracic fusion for Sprengel’s deformity [16], where a high degree of caudal reduction is required for treatment of a congenital high-riding scapula. This more aggressive reduction is particularly high risk for neurovascular complications such as BP injury. For this indication, techniques such as excision of part of the clavicle, morcellation of the clavicle, clavicular lengthening [7], and clavicular osteotomy have been described [16]. Some of these techniques, such as complete clavicle excision, clavicular osteotomy, and clavicular morcellation, would likely also have been effective in relieving the BP stretch for this patient. However, they would come at the cost of a full clavicular disconnection which would increase the level of invasiveness and risk of perioperative and future complications [17,18]. To our knowledge, dorsal claviculectomy as a prophylactic or treatment measure for BP stretch or compression has not been described in the context of scapulothoracic fusion or any other setting.

Additional strategies to help prevent and manage BP injuries related to scapulothoracic fusion procedures include the use of intraoperative neuromonitoring, performing intraoperative pulse checks of the distal upper extremity as a surrogate measure of neurovascular function, and early diagnosis and treatment if BP injuries occur.

BP and other neurovascular injuries are known complications of scapulothoracic fusion that can significantly affect quality of life. Downward stretch of the BP and narrowing of the costoclavicular interval are likely mechanisms for this type of injury, and dorsal claviculectomy can be considered as a treatment option to relieve the stretch and compression of the BP. Familiarity with this complication and measures to prevent and treat it are paramount for optimizing patient outcomes.

This article substantiates the utility of dorsal claviculectomy as an innovative treatment for brachial plexus injury post-scapulothoracic fusion, altering clinical practice by emphasizing early diagnosis and targeted interventions for improved patient outcomes.

References

- 1. Krishnan SG, Hawkins RJ, Michelotti JD, Litchfield R, Willis RB, Kim YK. Scapulothoracic arthrodesis: Indications, technique, and results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2005;435:126-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Eren I, Gedik CC, Kilic U, Abay B, Birsel O, Demirhan M. Management of scapular dysfunction in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: The biomechanics of winging, arthrodesis indications, techniques and outcomes. EFORT Open Rev 2022;7:734-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Eren I, Ersen A, Birsel O, Atalar AC, Oflazer P, Demirhan M. Functional outcomes and complications following scapulothoracic arthrodesis in patients with facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2020;102:237-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Duarte FH, Zerati AE, Gornati VC, Nomura C, Puech-Leao P. Normal costoclavicular distance as a standard in the radiological evaluation of thoracic outlet syndrome in the costoclavicular space. Ann Vasc Surg 2021;72:138-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kord D, Liu E, Horner NS, Athwal GS, Khan M, Alolabi B. Outcomes of scapulothoracic fusion in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy: A systematic review. Shoulder Elbow 2020;12:75-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Twyman RS, Harper GD, Edgar MA. Thoracoscapular fusion in facioscapulohumeral dystrophy: Clinical review of a new surgical method. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 1996;5:201-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Putti V. L’osteodesi interscapolare in un caso di miopatia atrofica progressiva. Arch Otrop 1906;23:319-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Bunch WH, Siegel IM. Scapulothoracic arthrodesis in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Review of seventeen procedures with three to twenty-one-year follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1993;75:372-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Berne D, Laude F, Laporte C, Fardeau M, Saillant G. Scapulothoracic arthrodesis in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;409:106-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Mackenzie WG, Riddle EC, Earley JL, Sawatzky BJ. A neurovascular complication after scapulothoracic arthrodesis. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2003;408:157-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Wolfe GI, Young PK, Nations SP, Burkhead WZ, McVey AL, Barohn RJ. Brachial plexopathy following thoracoscapular fusion in facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Neurology 2005;64:572-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Glenn RE, Romeo AA. Scapulothoracic arthrodesis: Indications and surgical technique. Tech Shoulder Elbow 2005;6:178-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Bhatia S, Hsu AR, Harwood D, Toleikis JR, Mather RC 3rd, Romeo AA. The value of somatosensory evoked potential monitoring during scapulothoracic arthrodesis: Case report and review of literature. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2012;21:e14-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Cooney AD, Gill I, Stuart PR. The outcome of scapulothoracic arthrodesis using cerclage wires, plates, and allograft for facioscapulohumeral dystrophy. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2014;23:e8-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Chen Y, Yu X, Huang W, Wang B. Is clavicular reconstruction imperative for total and subtotal claviculectomy? A systematic review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2018;27:e141-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Naik P, Chauhan H. Functional improvement in patients with sprengel’s deformity following modified green’s procedure and simplified clavicle osteotomy-a study of forty cases. Int Orthop 2020;44:2653-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Krishnan SG, Schiffern SC, Pennington SD, Rimlawi M, Burkhead WZ Jr. Functional outcomes after total claviculectomy as a salvage procedure. A series of six cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:1215-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Smolle MA, Niethard M, Schrader C, Bergovec M, Tunn PU, Friesenbichler J, et al. Clinical and functional outcome after partial or total claviculectomy without reconstruction for oncologic causes. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2023;32:1967-71. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]