Helps in treating a complicated case with proper pre-operative templating and how to handle its complications.

Dr. N Sharon Rose, Department of Orthopedics, ESIC Medical College and Hospital, Hyderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: rosesharon832@gmail.com

Introduction: The most common site of tumors is the femur in the adolescent group. As the tumour progresses in the proximal and distal metaphysis, the biomechanics of the hip and knee joints are changed, respectively. This case report is a coxa vara in an adolescent boy with fibrosis dysplasia – shepherd crook deformity, and a corrective osteotomy was done with some complications and success.

Case Report: A 12-year-old adolescent came with deformity of the right thigh with shortening, and radiograph shows fibrous dysplasia with coxa vara, which was treated with corrective osteotomy and medical management.

Conclusion: A proper clinical examination, pre-operative planning, finding CORA’s, anticipating intra-operative difficulties, and choice of implants result in massive efficacy in terms of both decision making and results in both radiologically and functionally.

Keywords: Coxa vara, fibrous dysplasia, osteotomy, denosumab, dynamic hip screw.

Fibrous dysplasia is a sporadic, non-inherited development skeletal disorder of the skeleton. Initially, it was identified by Lichtenstein in 1938 and described later by Lichtenstein and Jaffe in 1942. Accordingly, it was referred to as Lichtenstein-Jaffe disease. It is characterized by the presence of expanding intramedullary fibro-osseous tissue in one or more bones as a result of poorly formed, immature woven bone, giving a ground-glass appearance. It can be of monostotic or polyostotic type depending upon the number of bones involved. It is often associated with a severe Coxa vara in the femoral neck, often referred to as a Shepherd’s crook deformity. In this report, we present a case of severe coxa vara resulting in a double CORA at the neck and the shaft of the femur and will discuss its management and outcome [1].

A 12-year-old male child reported to our outpatient department with a deformity in the right proximal 1/3rd of the thigh for 6 years. There was a history of shortening of the right lower limb for 2 years and a painless limp for 5 years. He had a history of pain in the right hip joint for 3 weeks, which was aggravated on walking and activity and relieved with rest. There was no history of recent trauma. There was a history of trauma 8 years ago when he was hit by a vehicle and had taken a consultation elsewhere, where an open biopsy and curettage was done. There was no history of constitutional symptoms or small joint pathology. On local examination, there was postural lumbosacral scoliosis with convexity to the left side. There was anterolateral bowing in the proximal one-third of femur with a healthy surgical scar of biopsy on the lateral aspect. There was wasting of thigh and leg musculature when compared to the other side. The greater trochanter was not palpable, and there was abnormal thickening and irregularity over the deformity. Hip joint movements were restricted. They were café – laut- spots over the right scapula region, extending into the right axilla and chest. There is true shortening of 7 cm with short limb gait as shown in Fig. 1a and b.

Figure 1: (a) Pre-operative clinical images showing Café-lu spots at right scapula region, (b) Scoliosis at lumbosacral junction with convexity to left side and Anterolateral bowing of right thigh with pelvic obliquity (right sided is at higher level).

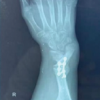

Radiographs showed severe coxa vara with proximal migration of the greater trochanter. Radiographs are shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Pre-operative radiograph – scannogram.

Biopsy reports done outside were suggestive of fibrous dysplasia. Considering the previous report and resembling clinical and radiological picture, it was decided not to repeat the biopsy and proceed with the definitive treatment.

Pre-operative plan

All the blood investigations were within the normal limits. The true shortening was 7 cm. Neck shaft angle was calculated to be 90° on the right side and 137° on the left side. First, CORA was found at the neck of the femur, and the second CORA was noted at the subtrochanteric level. The angle at the second CORA was 20°. The correction was planned. To achieve a neck shaft angle similar to the other side, the valgus osteotomy angle at the first CORA was found to be 45° (135° dynamic hip screw [DHS] – 90° native varus) (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Pre-operative scannogram showing Right coxa vara with fibrous dysplasia (shepherd crook deformity), Neck shaft angle – 124° (right side), 137° (left side), Right limb (femoral) shortening of 7 centimeters. 1st CORA- seating angle (90) of Richard’s screw center of head -angle of dynamic hip screw (135) = 45° and 2nd CORA – 20°.

Surgical procedure

The patient’s limb was fixed to the traction table; a lateral approach was taken. The center guide wire was passed into the center of the head and confirmed under fluoroscopy. Richard’s screw was passed, and the first valgus osteotomy at the subtrochanteric level was marked with k-wires. Osteotomy was done, and a barrel plate was inserted. The second osteotomy was based on the CORA in the shaft. The points were marked with k wires, and a corrective osteotomy of 20° was performed. Both the osteotomies were closed, and a long barrel plate was fixed to the shaft with distal screws. Finally, a compression lag screw was inserted. The wound was closed in layers over a drain. The patient was kept non-weight-bearing for 2 months. Limb length was achieved, and deformity was corrected. A wedge of bone was sent for biopsy, and it was interpreted as Fibrous dysplasia. Intra-operative images shown in Fig. 4. Follow-up post-operative images and Clinical improvement are shown in Fig. 5a and b.

Figure 4: Intra-operative images with double osteotomies at respective CORA’s.

Figure 5: (a) Post-operative radiograph showing gaining of mechanical axis and restoration of neck-shaft angle to 132° (b) Showing both ASIS at same level (Limb length gained).

However, after 4 weeks of post-operative period, there was backout of distal screws and failure of the implant (Fig. 6a). Hence, he was posted again for surgery, DHS barrel plate exchange (from 4-holed to 10-holed), and augmentation of distal screws with cement was done.

Figure 6: (a) After 4 weeks of immobilization, Back-out distal screws is seen (b and c) 6 months post-operative radiographs.

Patient was kept non-weight-bearing for 6 weeks, follow-up radiographs taken, which showed good union at osteotomies and no further signs of implant failure (Fig. 6b and c). The child is currently under follow-up for 1 year with no complications.

Fibrous dysplasia is classified as monostotic and polyostotic. Monostotic type involves one bone, asymptomatic till a pathological fracture. Polyostotic type- more severe, long bones, skull, vertebrae, pelvis, scapula, ribs, bones of hands and feet. Associated endocrinological abnormalities include precocious puberty, premature skeletal maturation, hyperthyroidism, hyperparathyroidism, acromegaly, and Cushing’s syndrome.

Mccune – Albright Syndrome includes Fibrous dysplasia [polyostotic] + café au lait spots + precocious puberty {mc in females. Mazabraud Syndrome includes Fibrous dysplasia [mono/polyostotic] + intramuscular myxomas. Cherubism is an autosomal disorder, presenting in the 2nd decade of life with Fibrous dysplasia + mandible and maxilla deformities. Management includes medical and surgical treatments. Medical management includes Bisphosphonates- pamidronate 0.5–1 mg/kg/day for 2–3 days 6 months–1 yearly interval, up to 3.5 years. Others are zoledronic acid, alendronate, oral calcium, and Vitamin D supplements.

In the present case, implant failure occurred due to osteoporotic bone and early weight-bearing. While augmentation techniques could have been attempted in the initial surgery, their success rate remains variable. Chen et al. reported two cases of shepherd’s crook deformity in polyostotic fibrous dysplasia (PFD) treated with corrective osteotomy and DHS. With follow-up periods ranging from 2 to 11 years, no recurrence or refracture was observed. Fixation was achieved using an 8-hole side plate in one case and a 6-hole side plate in the other [1].

A gamma nail may be another viable option, as it provides strong mechanical support for the femoral neck while exerting a lower bending moment compared to a DHS. However, in one case, the use of a gamma nail was abandoned because a 12-mm intramedullary nail and two distal screws failed to provide sufficient stability for the dysplastic bone, which was both thinned and widened. Moreover, the introduction of a gamma nail can be technically challenging, as locating an optimal entry point in a deformed proximal femur is difficult, increasing the risk of nail protrusion [2].

The surgical management of fibrous dysplasia has evolved over time. In 1950, Russell and Chandler reviewed 11 cases and suggested that surgical intervention is warranted for persistent pain at the lesion site, fractures, or severe deformities [3]. Yamamoto et al. described the benefits of oblique wedge osteotomy in a patient with three-dimensional diaphyseal deformity of the left femur, reporting good union, proper alignment, and no progression of varus deformity after 2 years of follow-up [4].

Stanton, however, discouraged the use of cortical grafts in proximal femur deformity associated with PFD, citing their slow resorption within dysplastic bone. He also advised against using plates and screws, emphasizing this in his “six do NOT work” surgical approach for PFD [5]. While some studies, such as Chen et al., have demonstrated successful outcomes with DHS in treating shepherd’s crook deformity, other reports indicate that stress concentration on the lower portion of the plates may lead to secondary deformities and challenges in conforming plates to the femoral contour [2].

Guille et al. studied a larger cohort of patients treated with curettage and autogenous bone grafting, but their findings showed complete resorption of all cancellous bone grafts without significant reduction or eradication of lesions on radiographic evaluation [6]. In cases where the femoral neck calcar is involved, medial displacement valgus osteotomy with overcorrection is recommended to create a more favorable mechanical environment for microfracture healing [7].

There is still a debate on using the methods of fixation in double-level osteotomies. Because in terms of intra-operative complications, stability, load-bearing biomechanics, there is still confusion. Extramedullary fixation gives good correction with reasonable surgical time and less fluoroscopy exposure. But it is also accompanying soft tissue dissection, wound healing issues, infections, bleeding, implant failure, peri-implant fractures due to load-bearing properties, and woven weak bone, and because of these, we need to avoid weight-bearing for longer than the usual time period. In this case, after we encountered with implant back out and a revision was done, we kept him non-weight bearing up to 4–5months, which cannot be promising in children and adolescents. Intramedullary fixation gives technical intraoperative difficulties in terms of entry point, reaming through a bent bone and fibrous tissue, passing the nail through multiple osteotomies, and allowing it to accommodate the CORAs. Yet, it gives good stability and early rehabilitation comparatively. The surgical planning included preoperative templating on 100% X-rays, and the entire plan was executed on templates. We used a traction table, being careful with weak woven bone, handling gently while creating the wedge at two levels, aligning the bone while closing the wedge without breaking the medial hinge. Older and obese children need a lot of force to close the wedge while abducting the limb, even on a traction table, and always use a long extramedullary device to hold multiple osteotomies.[8-11].

Fibrous dysplasia with shepherd-crook deformity is quite a challenge, which needs to be pre-planned well and be ready with all armor during intraoperative period, as we cannot trust the nature of bone and cannot depend on one type of implants alone.

Always plan properly in pre-operative period, in terms of procedure, implants, and anticipating difficulties in such complex deformities.

References

- 1. Jain K. Turek’s Orthopaedics Principles and their Applications. 7th ed. Netherlands: Wolters Kluwer; 2016. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Chen WJ, Chen WM, Chiang CC, Huang CK, Chen TH, Lo WH. Shepherd’s crook deformity of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia treated with corrective osteotomy and dynamic hip screw. J Chin Med Assoc 2005;68:343-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Russell LW, Chandler FA. Fibrous dysplasia of bone. J Bone Joint Surg 1950;32A:323-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Yamamoto T, Hashimoto Y, Mizuno K. Oblique wedge osteotomy for femoral diaphyseal deformity in fibrous dysplasia: A case report. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2001;384:245-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Stanton RP. Surgery for fibrous dysplasia. J Bone Miner Res 2006;21:105-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Guille JT, Kumar SJ, MacEwen GD. Fibrous dysplasia of the proximal part of the femur. Long-term results of curettage and bone-grafting and mechanical realignment. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1998;80:648-58. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Connolly JF. Shepherd’s Crook deformities of polyostotic fibrous dysplasia treated by osteotomy and Zickel nail fixation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1977;123:22-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Boyce AM. Denosumab: An emerging therapy in pediatric bone disorders. Curr Osteoporos Rep 2017;15:283-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Wang D, Tang X, Shi Q, Wang R, Ji T, Tang X, et al. Denosumab in pediatric bone disorders and the role of RANKL blockade: A narrative review. Transl Pediatr 2023;12:470-86. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Gounder M, Ratan R, Alcindor T, Schöffski P, Van Der Graaf WT, Wilky BA, et al. Nirogacestat, a γ-secretase inhibitor for desmoid tumors. N Engl J Med 2023:388:898-912. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Freeman BH, Bray EW 3rd, Meyer LC. Multiple osteotomies with Zickel nail fixation for polyostotic fibrous dysplasia involving the proximal part of the femur. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:691-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]