Spinal metastasis from an occult pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor can closely mimic infection on imaging, making early tissue diagnosis and timely decompression – supported by multidisciplinary management – critical for accurate diagnosis and optimal neurological recovery.

Dr. Anirudh Dwajan, Department of Orthopaedics, All India Institute of Medical Sciences, Bilaspur, Himachal Pradesh, India. E-mail: anirudhdwajan@gmail.com

Introduction: Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinomas are rare, high-grade malignancies accounting for <2% of pancreatic cancers. They frequently metastasize to the liver and lymph nodes, while skeletal involvement is uncommon. Spinal metastasis as the initial manifestation is exceedingly rare and poses a diagnostic challenge, especially for orthopedic surgeons who often encounter such lesions under the suspicion of infection or primary bone tumor.

Case Report: A 20-year-old male presented with acute-onset paraparesis and loss of bladder control. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging revealed destructive lesions at D1–D2 with epidural compression and additional vertebral deposits. Emergency decompression was done. Histopathology showed sheets of small round cells, and immunohistochemistry demonstrated positivity for Pan-cytokeratin, synaptophysin, CD56, CK20 (dot-like), and a high Ki-67 index (50–60%), confirming high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma. A whole-body positron emission tomography-computed tomography identified a metabolically active pancreatic tail mass with multiple hepatic, nodal, and skeletal metastases. The patient received four cycles of cisplatin–etoposide, followed by capecitabine and temozolomide for an incomplete response. Post-operative neurological function improved, and the patient remains ambulant with stable disease on serial imaging.

Conclusion: Spinal cord compression may exceptionally rarely be the presenting feature of pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. For orthopedic surgeons, early recognition of atypical spinal lesions, timely decompression, and prompt multidisciplinary referral are critical for achieving functional recovery and improving quality of life even in advanced systemic malignancy. High suspicion, tissue diagnosis, and timely decompression are essential for functional preservation.

Keywords: Pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma, spinal metastasis, spinal cord compression, dorsal spine decompression, orthopedic oncology

Neuroendocrine neoplasms (NENs) represent a diverse family of epithelial tumors that exhibit both endocrine and neural differentiation. They arise from the neuroendocrine cells scattered throughout multiple organ systems, most frequently within the gastrointestinal tract, pancreas, and bronchopulmonary tree. Although uncommon, their reported incidence has been steadily increasing due to improved imaging, endoscopic techniques, and heightened clinical awareness. Skeletal metastases from pancreatic primaries are most often osteoblastic, with thoracic vertebral involvement being distinctly uncommon [1].

Among these, pancreatic NENs constitute only 1–2% of all pancreatic malignancies and are broadly divided, according to the World Health Organization classification, into well-differentiated neuroendocrine tumors (NETs; G1–G3) and poorly differentiated neuroendocrine carcinomas (NECs; small- or large-cell types, always G3). The NEC subgroup displays highly aggressive biological behavior, characterized by rapid proliferation (Ki-67 index often exceeding 50%), early dissemination, and poor survival, with reported median overall survival as short as 5–6 months in metastatic cases. In contrast, well-differentiated NETs typically exhibit indolent growth and a more favorable prognosis [1,2].

The liver represents the most frequent site of metastasis in both NETs and NECs, followed by lymph nodes and, less commonly, the skeletal system. Bone metastases occur in approximately 5–20% of pancreatic malignancies, most often involving the axial skeleton, pelvis, or long bones. Spinal metastasis, particularly with cord compression as the initial presentation, is exceedingly rare and poses a diagnostic challenge, as radiological and histological appearances may overlap with other small round cell tumors, including lymphoma or primitive neuroectodermal tumor (PNET). Moreover, pancreatic primaries are seldom suspected in patients presenting primarily with spinal symptoms [3,4].

Early recognition of metastatic spinal involvement is essential, as prompt surgical decompression can prevent irreversible neurological damage and improve functional outcomes. Systemic chemotherapy – typically based on platinum and etoposide combinations – remains the cornerstone of treatment for high-grade NECs, with alternative regimens, such as capecitabine and temozolomide (CAPTEM) considered in patients showing suboptimal response or disease stability [5].

We present a rare case of high-grade pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma manifesting as acute D1–D2 spinal cord compression, initially suspected to be a PNET on morphology. The case emphasizes the pivotal role of immunohistochemistry in establishing the correct diagnosis and the importance of timely multidisciplinary management combining surgery and systemic therapy to achieve neurological recovery and disease control. Only a handful of cases describing spinal metastasis as the initial presentation of pancreatic NEC have been reported, underscoring the uniqueness of this case.

A 20-year-old male presented with complaints of mid-back pain and progressive weakness of both lower limbs over a period of approximately three weeks. The pain was insidious in onset, non-radiating, and had gradually increased in intensity. Approximately 3 weeks before admission, he noticed increasing difficulty in walking, which progressed from an unsteady gait to complete inability to stand or bear weight. Over the following few days, he also developed urinary retention and required catheterization. There was no associated history of fever, trauma, cough, weight loss, or loss of appetite. No similar episodes had occurred in the past, and there was no family history of malignancy or neurological disease.

On general physical examination, the patient was afebrile, hemodynamically stable, and did not appear toxic. No lymphadenopathy or organomegaly was noted. Local examination of the spine showed no visible deformity or swelling, but there was tenderness over the upper dorsal region. There was no gibbus or paraspinal fullness.

Neurological examination revealed increased tone in both lower limbs with exaggerated deep tendon reflexes. Power was approximately 3/5 in the proximal and 2/5 in the distal muscle groups of both legs. Plantar responses were bilaterally extensor, and ankle clonus was present. Sensory testing revealed loss of pinprick and light touch sensation below the T5 dermatome, while deep pressure was preserved. Perianal sensation was intact, but voluntary bladder control was lost, consistent with incomplete paraplegia, corresponding to ASIA Grade C neurological status. Examination of the upper limbs and cranial nerves was normal.

Systemic examination of cardiovascular, respiratory, and abdominal systems did not reveal any abnormalities. There was no palpable mass or lymph node enlargement. Based on the acute onset paraplegia with bladder involvement, an upper dorsal compressive myelopathy was suspected, and urgent imaging was advised.

Investigations

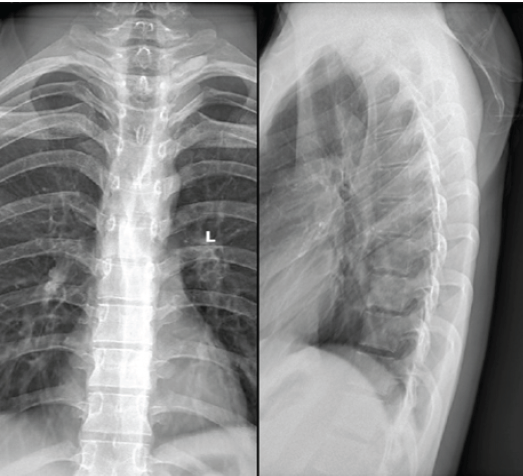

Plain radiographs of the thoracic spine were obtained at presentation. On anteroposterior and lateral views, there was a mild loss of definition of the D1–D2 endplates with minimal reduction of anterior vertebral height at D2. The posterior cortical outline appeared indistinct, although there was no frank collapse or deformity. The overall appearance suggested a destructive vertebral process and prompted urgent cross-sectional imaging (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Pre-operative radiographs (anteroposterior and lateral views) of the dorsal spine showing irregularity and loss of cortical definition at the D1–D2 vertebral levels with mild anterior height reduction of D2, suggestive of a destructive vertebral lesion.

Baseline laboratory investigations revealed hemoglobin and platelet counts within normal limits. Liver and renal function tests were normal. Inflammatory parameters, including erythrocyte sedimentation rate and C-reactive protein, were not significantly elevated. Serum calcium and alkaline phosphatase values were also within normal range, with no biochemical evidence of infection or metabolic bone disease.

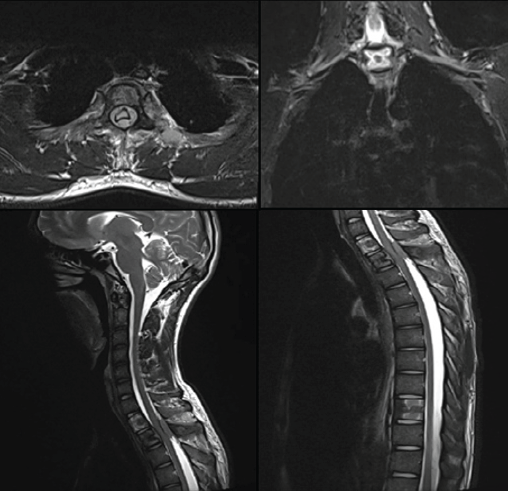

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the dorsal spine demonstrated altered marrow signal and heterogeneous post-contrast enhancement involving the D1, D2, and D10 vertebral bodies. An enhancing soft-tissue mass extended into both anterior and posterior epidural spaces at the D1–D2 level, causing severe spinal canal narrowing with cord compression and myelopathic signal changes. Extension was noted along the bilateral neural foramina and posterior elements of D1–D3 (Fig. 2). Additional short tau inversion recovery-hyperintense foci were seen in D11, D12, L1, L3, and L5 vertebrae, several of which showed mild enhancement, raising concern for multifocal metastatic deposits.

Figure 2: Pre-operative magnetic resonance imaging of the dorsal spine showing altered marrow signal and enhancing lesion involving the D1–D2 vertebral bodies with an epidural soft-tissue component causing severe spinal canal narrowing and cord compression with associated myelopathic signal changes. Additional axial and sagittal sequences demonstrate the extent of epidural involvement and compression.

Contrast-enhanced computed tomography (CT) of the chest and abdomen revealed no significant intrathoracic disease apart from a tiny non-specific peribronchial nodule in the apicoposterior segment of the left upper lobe. A large, heterogeneously hypoenhancing retroperitoneal mass was visualized in the lesser sac, extending toward the distal pancreas and splenic hilum and abutting the gastric wall and adjacent bowel loops, with areas of internal necrosis. The lesion caused obliteration of surrounding fat planes and vascular encasement, with splenic infarcts suggesting vascular compromise. Multiple enlarged para-aortic lymph nodes were also noted. Sclerotic changes in D1, D2, and D9 vertebral bodies further supported possible metastatic involvement.

In view of acute neurological deterioration, the patient underwent emergency posterior decompression and stabilization at D1–D2. Intra-operative findings included a soft, grey-brown friable lesion replacing the posterior elements and compressing the dural sac. Representative tissue was sent for histopathological and microbiological evaluation. Bacterial and fungal cultures were negative.

Microscopic examination showed sheets of darkly stained tumor cells arranged in infiltrating nests. These cells expressed neuroendocrine markers with dot-like CK20 positivity. Immunohistochemical profiling demonstrated diffuse reactivity for Pan-cytokeratin, CD56, and synaptophysin, with patchy chromogranin and neuron-specific enolase positivity. CK20 showed perinuclear dot positivity, while thyroid transcription factor – 1 was weakly to moderately positive. The tumor was negative for CK7, NKX2.2, FLI-1, leukocyte common antigen (LCA), PAX5, smooth muscle actin, MyoD1, WT-1, glial fibrillary acidic protein (GFAP), and S-100. Desmin showed focal reactivity, and CD99 demonstrated non-specific cytoplasmic staining. The Ki-67 proliferation index was approximately 50–60%, indicating high-grade malignancy.

These findings confirmed the diagnosis of a high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, likely metastatic in nature, and effectively ruled out a PNET. A Merkel-cell carcinoma was considered due to CK20 dot-like staining but deemed improbable in the absence of a skin lesion.

Given the multifocal vertebral and visceral lesions, a systemic primary was suspected, prompting staging with whole-body FDG PET-CT. A baseline whole-body 18F-fluorodeoxyglucose (FDG) positron emission tomography (PET)-CT confirmed a metabolically active pancreatic tail mass measuring approximately 7.8 × 6.4 cm (SUVmax 8.9), with encasement of the splenic vein and involvement of the adjacent splenic parenchyma. Multiple FDG-avid retroperitoneal and peripancreatic nodes (largest 2.0 × 1.8 cm, SUVmax 6.9) and a segment IV hepatic lesion (SUVmax 5.2) were noted. Numerous sclerotic, FDG-avid osseous metastases involved the dorsolumbar spine, sacrum, pelvis, ribs, bilateral femora, and left scapula. An additional soft-tissue lesion at the left lateral aspect of D2 (SUVmax 7.2) showed mild intraspinal extension. Small FDG-avid pulmonary nodules (7 × 4 mm, SUVmax 2.8) were seen bilaterally, consistent with disseminated disease.

A follow-up PET-CT performed 2 months after initiation of chemotherapy showed a partial metabolic response. The pancreatic lesion remained stable in size but demonstrated reduced FDG uptake. Retroperitoneal and peripancreatic lymph nodes decreased in size and activity. The hepatic and marrow lesions showed low-grade residual activity with interval metabolic regression, and the osseous metastases exhibited increasing sclerosis with declining FDG uptake. The previously seen pulmonary nodules had resolved completely.

After 5 months of chemotherapy, repeat PET-CT demonstrated stable disease. The pancreatic primary remained similar in size but showed a mild increase in metabolic activity (>30% SUVmax rise). Retroperitoneal lymph nodes and hepatic lesions showed minor metabolic progression, while skeletal metastases displayed extensive sclerosis and mixed activity. No new lesions were seen. Overall, findings were consistent with morphological stability and mild metabolic progression.

At 6 months post-chemotherapy, contrast-enhanced MRI of the pelvis and whole spine revealed multiple soft-tissue and bony deposits. A 1.6 × 1.8 cm enhancing lesion was identified in the rectovesical pouch and another 1.5 × 1.1 cm lesion near the right piriformis muscle, both suggestive of metastatic pelvic lymph nodes. Multiple soft-tissue deposits were seen in the bilateral iliac blades, cervical, dorsal, and lumbar vertebrae, extending into paravertebral spaces. Enhancing extradural lesions were again seen at D1–D2, causing thecal sac narrowing with cord expansion and myelopathic changes, corresponding to the prior decompression site and likely representing a combination of residual tumor and post-surgical enhancement.

Together, the serial imaging studies demonstrated a metastatic neuroendocrine carcinoma with partial but incomplete response to chemotherapy, showing residual disease in the pancreas, retroperitoneal nodes, and spine, along with interval development of new pelvic metastatic deposits.

Treatment

In view of acute neurological deterioration and imaging findings suggestive of high dorsal spinal cord compression, the patient underwent emergency posterior decompression and stabilization at the D1–D2 level.

The decision for posterior decompression without instrumentation was guided by the patient’s acute neurological deterioration and radiological evidence of cord compression, in the absence of significant mechanical instability on imaging. According to the Spinal Instability Neoplastic Score, the lesion was classified as potentially unstable; however, given the lack of gross deformity and the limited extent of bony destruction, decompression alone was considered appropriate to achieve neurological recovery and maintain spinal alignment.

Intra-operatively, a friable grey-brown soft tissue mass was identified replacing the posterior elements and compressing the Dural sac. Adequate decompression was achieved, and tissue samples were sent for histopathological and microbiological analysis.

Following histopathological confirmation of metastatic high-grade neuroendocrine carcinoma, the patient was referred to the Department of Medical Oncology for systemic therapy. Combination chemotherapy with cisplatin and etoposide was initiated, administered in four cycles over a period of 4 months. The patient tolerated the regimen well with no major adverse events.

As the interim PET-CT evaluation demonstrated incomplete metabolic response, the chemotherapy protocol was subsequently modified to include CAPTEM as second-line therapy. At the time of the latest review, the patient had completed two cycles of CAPTEM and continued to be on the same regimen with close oncological supervision.

Outcome

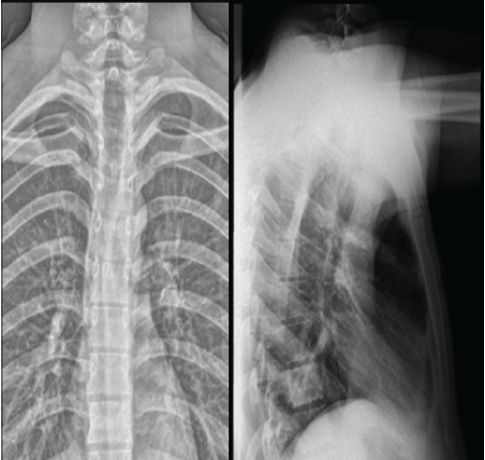

Neurological improvement was observed soon after decompression surgery. At 6 weeks post-operatively, motor strength had improved to 4+/5 in most key lower limb muscle groups with regained bladder continence, corresponding to ASIA Grade D (Fig. 3). This functional recovery underscores the importance of early surgical decompression in patients presenting with acute metastatic cord compression.

Figure 3: Six-week post-operative radiographs (anteroposterior and lateral views) showing maintained spinal alignment and stable post-operative changes at the D1–D2 level with satisfactory decompression and no evidence of progression of disease.

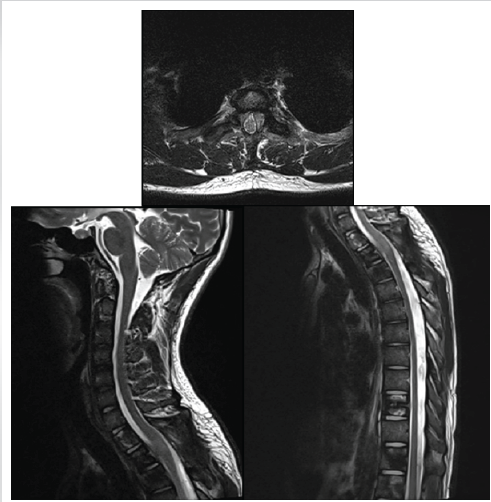

Serial follow-up PET-CT scans showed an initial partial metabolic response after four cycles of cisplatin–etoposide, followed by stable disease with mild metabolic progression after 5 months of therapy. The most recent MRI of the pelvis and whole spine, performed 6 months after initiation of chemotherapy, demonstrated residual enhancing deposits at D1–D2 with additional metastatic lesions in the pelvis and iliac bones, consistent with partial but incomplete response (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Six-week post-operative magnetic resonance imaging of the dorsal spine showing adequate decompression of the spinal cord at the D1–D2 level with resolution of cord compression and myelopathic changes. Mild post-operative enhancing soft tissue is seen along the posterior margin.

Clinically, the patient remains ambulant with mild lower limb weakness, stable neurological function, and no new deficits (Fig. 5). He continues on maintenance chemotherapy with scheduled PET-CT surveillance every 2 months to assess further response and disease progression.

Figure 5: Post-operative clinical photograph showing the patient ambulant and walking independently 6 weeks after decompression surgery, demonstrating significant neurological recovery and functional improvement.

NENs of the pancreas comprise a biologically diverse group of tumors ranging from indolent, well-differentiated lesions to highly aggressive carcinomas. Poorly differentiated pancreatic NECs account for <5% of pancreatic malignancies but display rapid proliferation, early dissemination, and poor prognosis. [6].

The liver and lymph nodes are the most frequent metastatic sites, while skeletal involvement occurs in only 5–20% of cases. Spinal metastasis, particularly with cord compression as the initial presentation, is exceedingly rare and generally indicates advanced disease [7].

From an orthopedic perspective, this case underscores the diagnostic and therapeutic challenges posed by destructive spinal lesions without a known primary. The patient initially presented with acute compressive myelopathy, a scenario commonly attributed to infectious or primary spinal pathology in orthopedic practice. Radiographs demonstrated subtle endplate irregularity, and MRI suggested a destructive vertebral process at D1–D2, mimicking tuberculosis or a small round cell tumor. However, the absence of disc involvement, presence of multiple vertebral lesions, and associated paravertebral mass favored a metastatic process. This highlights the importance for orthopedic surgeons to maintain a broad differential diagnosis and prioritize biopsy confirmation in atypical spinal lesions before definitive intervention.

Histopathological examination revealed sheets of small, round to oval tumor cells with scant cytoplasm and hyperchromatic nuclei, initially suggesting a PNET. Immunohistochemistry, however, provided diagnostic clarity: Tumor cells showed diffuse positivity for Pan-cytokeratin, synaptophysin, and CD56, confirming epithelial and neuroendocrine differentiation. CK20 displayed perinuclear dot positivity, and TTF-1 was weakly positive, while chromogranin and NSE were patchy. The tumour was negative for lymphoid markers (LCA, CD3, CD20), myogenic markers (MyoD1 and desmin, with only focal desmin positivity), and neural-crest markers (S-100, GFAP). Additionally, NKX2.2, CD99, and FLI-1—typically expressed in PNETs and other Ewing family tumours—were negative, effectively excluding this differential diagnosis. T Ki-67 index of 50–60% confirmed a high-grade (G3) neuroendocrine carcinoma rather than a well-differentiated NET [8].

Correlation with PET-CT showing a metabolically active pancreatic tail mass established the primary pancreatic origin.

The diagnostic overlap between small round cell neoplasms, such as NEC, PNET, and lymphoma is well-recognized [1,2]. For the treating orthopedic surgeon, understanding this overlap is essential to avoid misdiagnosis, particularly in resource-limited settings where tuberculosis or primary sarcoma is often presumed. Immunohistochemistry remains the definitive tool to distinguish these entities, allowing accurate oncological referral and prognostication.

Surgical intervention in spinal metastasis primarily aims to preserve or restore neurological function, rather than achieve oncological cure. In this case, the decision for urgent D1–D2 decompression and stabilization was guided by the patient’s rapidly progressive neurological deficit, consistent with accepted orthopedic oncology principles prioritizing neural salvage. Early decompression led to significant improvement in motor function and bladder control, validating the principle that timely surgery can produce meaningful functional recovery even in disseminated disease.

Subsequent systemic therapy with cisplatin and etoposide achieved a partial metabolic response after four cycles. On detecting residual disease, chemotherapy was switched to CAPTEM, a regimen increasingly recognized as effective in high-grade NECs with slower progression [5,9,10,11,12].

The patient remains ambulant and functionally independent, demonstrating that coordinated multimodal care can provide quality-of-life benefits even when long-term prognosis remains guarded.

This case holds several key lessons for orthopedic surgeons. First, spinal metastasis may be the initial manifestation of an occult visceral malignancy, and pancreatic origin, though rare, should be considered in the differential diagnosis of multifocal spinal lesions. Second, radiological patterns and early biopsy are critical for distinguishing metastatic from infective or primary bone pathology. Third, urgent decompression in neurologically compromised patients provides the best chance for functional recovery and independence, aligning with the “surgery for function” philosophy central to spinal oncology. Finally, multidisciplinary management – involving orthopedics, oncology, pathology, and radiology – is essential for optimizing outcomes in such complex cases.

In summary, metastatic high-grade pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma presenting as spinal cord compression is extraordinarily rare. For orthopedic surgeons, the clinical lesson lies in maintaining a high index of suspicion for metastatic disease when encountering atypical destructive spinal lesions – particularly those lacking disc involvement and showing normal inflammatory markers, even in younger adults. Prompt tissue diagnosis and timely decompression remain the cornerstones of effective care. Even in advanced systemic disease, surgical intervention can decisively influence neurological recovery, functional independence, and overall quality of life.

Please check the edit made.

Metastatic involvement of the spine from a pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma is exceptionally rare and may present as the first manifestation of the disease. For orthopedic surgeons, such cases highlight the importance of maintaining a broad differential diagnosis for destructive spinal lesions and prioritizing early tissue diagnosis. Prompt surgical decompression remains the cornerstone of management in patients presenting with neurological compromise, offering the best chance for functional recovery even in disseminated malignancy. Multidisciplinary coordination between orthopedics, oncology, pathology, and radiology is essential to achieve optimal palliation and preserve quality of life.

Spinal cord compression may be the initial manifestation of an occult pancreatic neuroendocrine carcinoma. For orthopedic surgeons, early recognition of metastatic pathology, timely decompression, and multidisciplinary coordination are crucial to preserve neurological function and improve quality of life even in advanced systemic disease.

References

- 1. Leng A, Zhong N, He S, Liu Y, Yang M, Jiao J, et al. Symptomatic spinal metastases from neuroendocrine neoplasms: Surgical outcomes and prognostic analysis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 2021;207:106710. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Radu EC, Saizu AI, Grigorescu RR, Croitoru AE, Gheorghe C. Metastatic neuroendocrine pancreatic tumor – Case report. J Med Life 2018;11:57-61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Survival Rates for Pancreatic Neuroendocrine Tumor. ACS; 2023. Available from: https://www.cancer.org/cancer/types/pancreatic-neuroendocrine-tumor/detection-diagnosis-staging/survival-rates.html [Last accessed on 2025 Feb 12]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Sundin A, Arnold R, Baudin E, Cwikla JB, Eriksson B, Fanti S, et al. ENETS consensus guidelines for the standards of care in neuroendocrine tumors: Radiological, nuclear medicine & Hybrid Imaging. Neuroendocrinology 2017;105:212-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Kos-Kudła B, Castaño JP, Denecke T, Grande E, Kjaer A, Koumarianou A, et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumour Society (ENETS) 2023 guidance paper for nonfunctioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumours. J Neuroendocrinol 2023;35:e13343. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Milan SA, Yeo CJ. Neuroendocrine tumors of the pancreas. Curr Opin Oncol 2012;24:46-55. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Cerwenka H. Neuroendocrine liver metastases: Contributions of endoscopy and surgery to primary tumor search. World J Gastroenterol 2012;18:1009-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Bocchini M, Nicolini F, Severi S, Bongiovanni A, Ibrahim T, Simonetti G, et al. Biomarkers for pancreatic neuroendocrine neoplasms (PanNENs) management-an updated review. Front Oncol 2020;10:831. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Hofland J, Falconi M, Christ E, Castaño JP, Faggiano A, Lamarca A, et al. European Neuroendocrine Tumor Society 2023 guidance paper for functioning pancreatic neuroendocrine tumour syndromes. J Neuroendocrinol 2023;35:e13318. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Rikhraj N, Fernandez CJ, Ganakumar V, Pappachan JM. Pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors: A case-based evidence review. World J Gastrointest Pathophysiol 2025;16:107265. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Kim JH, Hyun CL, Han SH. Intramedullary spinal cord metastasis from pancreatic neuroendocrine tumor. World J Gastroenterol 2014;20:14063-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Rail B, Ogwumike E, Adeyemo E, Badejo O, Barrie U, Kenfack YJ, et al. Pancreatic cancer metastasis to the spine: A systematic review of management strategies and outcomes with case illustration. World Neurosurg 2022;160:94-101.e4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]