Semitendinosus tendon represents a viable biological option for meniscal reconstruction.

Dr. Miguel Afonso Rocha, Department of Orthopaedics and Traumatology, Local Health Unit of Alto Ave, Hospital da Senhora da Oliveira, R. dos Cutileiros 114, 4835-044 Guimarães, Portugal. E-mail: miguelafonsorocha3@gmail.com

Introduction: The detrimental consequences of untreated meniscal tears or total meniscectomy, including impaired rotatory stability, increased sagittal laxity, and accelerated cartilage degeneration, are well documented, even though meniscectomy is still the most commonly performed procedure. Meniscus allograft transplantation remains the gold standard for meniscal substitution; however, its limited availability highlights the need for safe and effective autologous alternatives. Emerging evidence supports the use of autologous tendon grafts, particularly the semitendinosus tendon, as promising biological substitutes, offering a viable solution to allografts and synthetic implants.

Case Report: A 39-year-old woman presented with lateral knee pain and swelling, 29 years after undergoing a subtotal lateral meniscectomy at age 10. Clinical examination revealed lateral joint line tenderness and a range of motion (ROM) of 0–120. Radiographs and magnetic resonance imaging showed degenerative changes in the residual lateral meniscus, cartilage defects in the lateral compartment, and intra-articular loose bodies. Following initial arthroscopy and persistent symptoms, a lateral meniscus autograft transplantation using a hamstring tendon was performed. Post-operative rehabilitation included a progressive ROM limitation: 0°–30° (weeks 0–3), 0°–60° (weeks 3–6), and 0°–90° (weeks 6–8). Partial weight-bearing was allowed for 4 weeks, progressing to full weight-bearing at 8 weeks; squatting was restricted for 4 months. Jogging was initiated at 3 months, with return to sport at 6 months. At 1-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic with a 15 gain in flexion and significant improvement in all functional scores (Lysholm score, International Knee Documentation Committee score, and Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score).

Conclusion: This case supports the growing evidence that, with careful surgical planning and appropriate patient selection, autologous tendon grafts represent a viable biological option for meniscal reconstruction. This approach may be particularly beneficial in middle-aged patients, in whom joint preservation remains a key therapeutic goal.

Keywords: Meniscal transplant, autologous tendon graft, semitendinosus tendon, lateral meniscus.

The meniscus is a fibrocartilaginous structure essential to the normal biomechanics of the knee joint. Its primary functions include the distribution and dissipation of axial loads across the tibiofemoral joint through the integrated architecture of radial and circumferential collagen fibers; enhancement of joint stability and congruity by increasing the articular contact area and limiting excessive movement; as well as protection of the articular cartilage, shock absorption, facilitation of joint lubrication, and contribution to proprioceptive feedback [1,2]. The meniscus composition reflects this functional relevance, being formed by distinct meniscal cell populations embedded within an extracellular matrix predominantly composed of type I collagen fibers, together with proteoglycans, glycoproteins, non-collagenous proteins, and water [3].

The stability and structural integrity of the menisci are maintained not only by their intrinsic collagen architecture but also by several secondary attachments. Anteriorly, the medial and lateral menisci are interconnected by the anterior intermeniscal ligament, a distinct fibrous band that unites their anterior horns. The coronary (meniscotibial) ligaments anchor the capsular margins of the menisci to the tibial plateau, providing stronger fixation on the medial side compared to the lateral, thereby explaining the medial meniscus’s reduced mobility.

Furthermore, the meniscofemoral ligaments – namely, the ligaments of Humphrey and Wrisberg – originate from the posterior horn of the lateral meniscus and insert onto the lateral aspect of the medial femoral condyle. These ligaments play a crucial role in stabilizing and protecting the lateral meniscus while acting synergistically with the posterior cruciate ligament to enhance posterior knee stability [4,5].

Meniscus injuries represent the most common intra-articular injury in the United States [6]. Historically, total or partial meniscectomy was the standard treatment. However, in 1948, Fairbank demonstrated that total medial meniscectomy leads to rapid development of osteoarthritis (OA), fundamentally shifting the understanding of meniscal function [7,8]. The next landmark development in meniscal preservation occurred over 30 years ago when Henning developed and popularized the technique of meniscus repair [9].

At present, a substantial proportion of meniscal tears still requires surgical intervention, with meniscectomy remaining the predominant procedure [6]. Yet, the deleterious sequelae of untreated tears or total meniscectomy, such as impaired rotatory stability, increased sagittal laxity, and accelerated cartilage degeneration, are now well established. Consequently, a paradigm shift toward joint preservation and minimally invasive surgery has emerged, encapsulated by the principle “save the meniscus” [10,11]. This evolution underscores an urgent need to improve current treatment strategies, refine surgical techniques, and reinforce the global mindset surrounding meniscal preservation.

Recent decades have seen the development of biological and reconstructive options aimed at restoring meniscal function and mitigating the long-term consequences of meniscal loss. These include meniscal repair, allograft transplantation, and scaffold implantation, all of which aim to reduce cartilage damage and delay OA progression [12]. Among these, tendon autografts have recently gained prominence as promising substitutes, offering superior safety, ready availability, and biocompatibility while avoiding the immunogenic and infectious risks associated with allografts [13].

Contemporary evidence highlights autologous tendon grafts, particularly the semitendinosus tendon (ST), as viable biological alternatives to allografts and synthetic implants. A comprehensive review by Japanese and Swedish researchers synthesized pre-clinical and clinical data supporting this approach, detailing surgical techniques, graft integration, and biomechanical outcomes [13]. The review also emphasized practical advantages, including autograft accessibility and absence of immunologic reaction, while acknowledging limitations related to the tendon’s inability to fully replicate the native meniscus’s complex viscoelastic properties.

Accordingly, the present case report aims to describe the clinical outcomes of lateral meniscus reconstruction using a double-stranded ST, thereby contributing to the expanding body of evidence supporting this technique as a viable and effective biological substitute for meniscal loss.

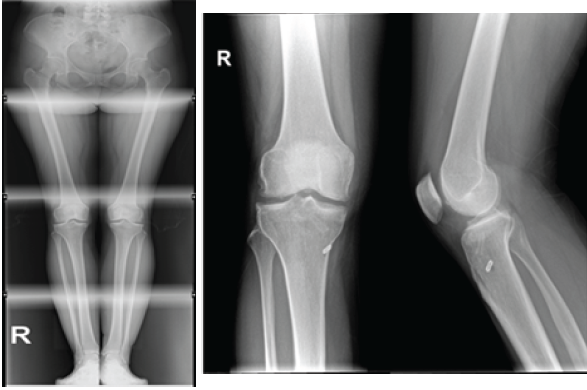

The patient was a 39-year-old woman who presented with right knee pain. She had undergone a subtotal lateral meniscectomy when she was 10 years old. For a while, she was able to exercise without any symptoms; however, she started to experience pain on the lateral side of the knee with swelling 6 years before. Physical examination revealed swelling and tenderness of the lateral knee joint. The range of motion (ROM) of her knee joint was 0°–120°. An X-ray with the Rosenberg view (standing posteroanterior view with 45° knee flexion) and a magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) revealed acceptable cartilage defects in the lateral compartment and residual lateral meniscus with degenerative changes and small loose bodies.

Initially, the patient was submitted to arthroscopy, it was observed cartilage defects with International Cartilage Repair Society grade III in the lateral compartment and removal of loose bodies was done. If the meniscus were repairable, attempts would be made to repair the meniscus, since the decision of meniscal transplant is made only when a significant amount (subtotal or total meniscectomy) of the meniscus is removed, which was the case.

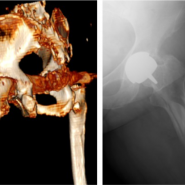

Due to the refractory pain and persistent difficulty in performing daily activities 1 year later, a weight-bearing full-leg X-ray was performed (Fig. 1) and showed a neutral aligned knee with a hip-knee-ankle angle of 1° varus and normal values for the lateral distal femoral angle and the medial proximal tibial angle. Operative treatment with lateral meniscus autograft transplantation using a hamstring tendon was proposed.

Figure 1: Full-leg X-ray.

Surgical technique

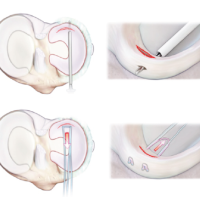

A standard diagnostic arthroscopy was performed using anteromedial and anterolateral portals. Residual meniscal tissue was removed, preserving the peripheral rim as much as possible. Multiple peripheral fenestrations were performed along the meniscal rim to improve vascular penetration, thereby promoting graft integration and facilitating subsequent suturing. The ST was harvested using a closed tendon stripper. Following harvest, all residual muscle tissue was carefully removed.

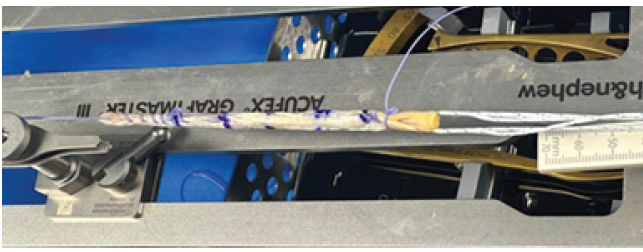

The proximal flat portion of the tendon was folded over the distal rounded portion to form a double-stranded loop. This folded segment was secured using a continuous 2-0 Vicryl suture, while both free ends were prepared with whipstitch sutures. A reference mark was made 25 mm from the posterior end of the graft using a sterile dermographic marker to guide the positioning of the posterior meniscal root within the tibial tunnel, ensuring adequate intraosseous integration (Fig. 2). In addition, a central suture was placed along the remaining portion of the graft using a no. 2 high-strength suture to assist with graft manipulation and positioning during implantation (Fig. 3).

Figure 2: Double-folded semitendinosus tendon with sutures.

Figure 3: Central suture.

Anatomical anterior and posterior root tunnels were created using a meniscus root guide and an inside-out reamer, with diameters matched to the graft (6 mm) and a minimum inter-tunnel distance of 1.5–2 cm on the tibial surface to avoid convergence. The prepared graft measured 14 cm in length. It was introduced into the joint through the anteromedial portal, with the folded posterior end first guided into the posterior root tunnel (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Posterior end with cortical button.

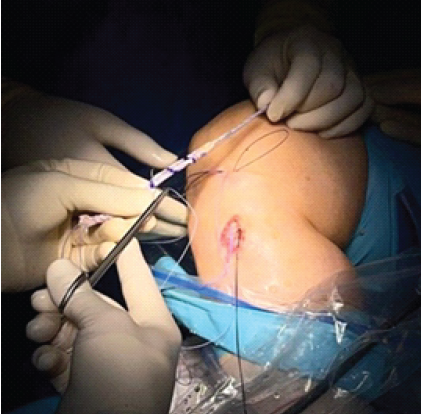

Using a suture shuttle technique, the graft was centralized and approximated to the remaining native meniscus and capsule, assisted by a blunt instrument to ensure secure contact. The anterior sutures were passed through the anterior tunnel and pulled distally to tension and fix the graft. Additional fixation was performed using all-inside, inside-out, and outside-in sutures around the graft body for reinforcement.

Final tibial fixation was achieved with a cortical button at the posterior root tunnel and an interference screw in the anterior tunnel.

Post-operative rehabilitation and clinical outcomes

The rehabilitation protocol followed in this specific case was with limitation of the knee ROM to 0°–30° during the first 3 weeks, progressively increased to 0°–60° between weeks 3 and 6, and further extended to 0°–90° from weeks 6 to 8 postoperatively. Partial weight-bearing was permitted during the first 4 weeks, with progression to full weight-bearing at 8 weeks. Weight bearing while squatting was restricted for the first 4 months. Jogging was initiated at 3 months, and return to pre-injury sports activities was allowed at 6 months.

At the 1-month follow-up, the patient demonstrated knee flexion up to 60°, in accordance with the post-operative protocol, and reported only mild pain at full extension. Clinical inspection revealed well-healed incisions without inflammatory changes or signs of local infection (Fig. 5). The patient reported no episodes of instability, and the knee was stable on examination, with a negative Lachman test and no laxity under varus or valgus stress at both 0° and 30°.

Figure 5: 1-month follow-up.

At 3 and 6 months, the patient had a ROM of 0–135° and it was without any complaints, although maintaining mild pain at full extension.

At the 1-year follow-up, the patient was asymptomatic, with no lateral joint pain or swelling during physical activity. The patient reported the absence of pain throughout the full ROM. The post-operative Tegner activity score was 6. Knee ROM had improved to 0°–135°, reflecting a gain of 15° from her pre-operative status (Fig. 6). The McMurray test was negative.

Figure 6: Complete range of motion at 1-year follow-up.

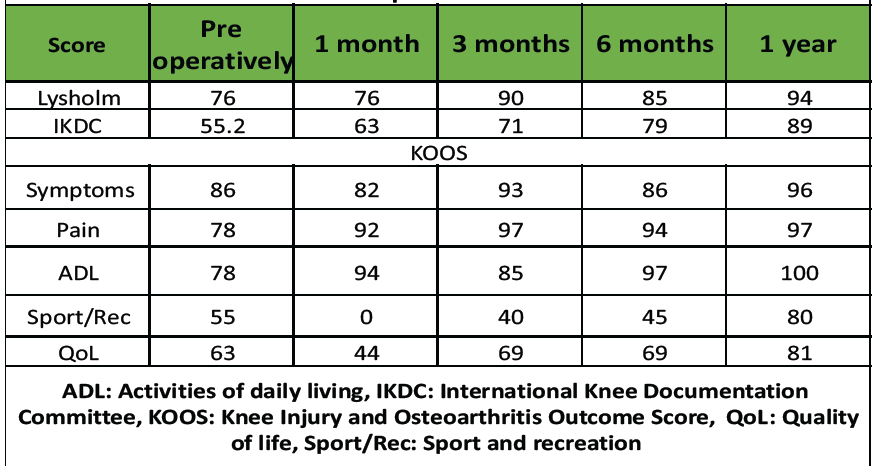

Functional outcomes (Table 1) also showed significant improvement: The Lysholm score increased from 76 preoperatively to 94, the International Knee Documentation Committee score improved from 55.2 to 89, and the Knee Injury and OA Outcome Score (KOOS) increased in the five dimensions (KOOS symptoms from 86 to 96, KOOS pain from 78 to 97, KOOS activities of daily living from 78 to 100, KOOS Sport/Rec from 55 to 80, KOOS QoL from 63 to 81).

Table 1: Patient-reported outcome measures

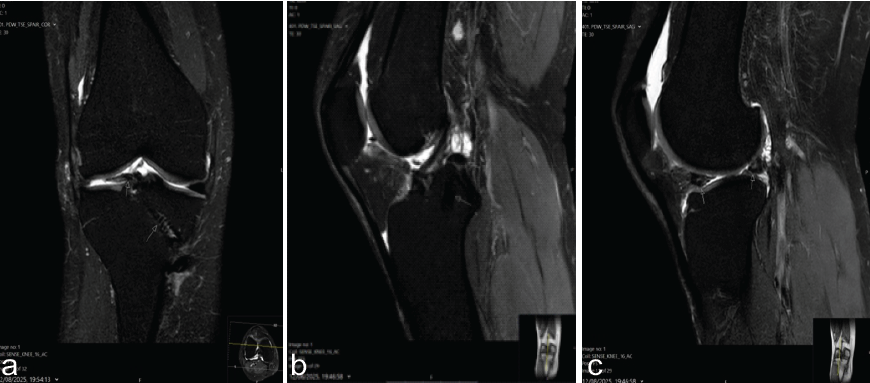

MRI examinations were obtained preoperatively, as well as at 6 and 12 months postoperatively. At the 1-year follow-up, MRI demonstrated correct positioning of the anterior and posterior roots and their corresponding tunnels, with a residual meniscal hypersignal on T2 sequences (Fig. 7).

Figure 7: Magnetic resonance imaging T2 sequences. (a) Coronal section showing the anterior root of the external meniscus graft (left arrow) and the anterior tibial tunnel (right arrow). (b) Sagittal section showing the posterior root of external meniscus graft (upper arrow) and the posterior tibial tunnel (lower arrow). (c) Sagittal section showing the anterior and posterior roots of external meniscus grafts.

While meniscus allograft transplantation continues to represent the most established method of meniscal substitution [14], its limited availability underscores the importance of developing safe and effective autologous alternatives. Autografts, such as the ST, offer clear advantages of accessibility, safety, and biocompatibility, without the risks of immunogenicity.

In a recent biomechanical study, Seitz et al. evaluated autologous tendon grafts, specifically a doubled semitendinosus and a single gracilis tendon (GT) graft, for lateral meniscus reconstruction in human cadaveric knees following total meniscectomy. Their findings demonstrated that the doubled ST graft substantially restored joint kinematics and tibiofemoral contact pressures to values approximating those of the intact native knee. From a biomechanical perspective, these results suggest that ST autografts may outperform GT autografts as reconstructive options for meniscal substitution [15].

This case demonstrates the successful use of an autologous double-stranded ST graft for lateral meniscus reconstruction in a 40-year-old patient, with excellent clinical outcomes. The patient reported marked pain relief and a significant improvement in quality of life, achieving her primary goal of regaining functional capacity in daily living while delaying the onset of osteoarthrosis. These results are particularly relevant in this age group, where meniscal preservation remains a surgical challenge, and individualized planning is essential to ensure both joint protection and long-term functionality.

The neutral pre-operative alignment of the knee further contributed to the favorable outcome, as excessive varus or valgus malalignment may jeopardize graft survival and overall success. Patient-reported outcomes should still be interpreted with caution in the early rehabilitation phase, given their subjective nature and dependence on the recovery process.

In summary, this case reinforces that, with careful surgical planning and appropriate patient selection, autologous tendon grafts may serve as a valuable biological substitute for meniscal reconstruction, particularly in middle-aged patients, for whom joint preservation strategies are crucial. Nevertheless, further clinical studies are needed to validate the long-term effectiveness and broader applicability of this technique.

Using the ST as an autologous graft appears to be a promising option for meniscal reconstruction and should be further explored. By developing well-defined indications for different techniques, we can move toward more personalized treatment strategies and better outcomes for patients.

References

- 1. Mameri ES, Dasari SP, Fortier LM, Verdejo FG, Gursoy S, Yanke AB, et al. Review of meniscus anatomy and biomechanics. Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med 2022;15:323-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Pasiński M, Zabrzyńska M, Adamczyk M, Sokołowski M, Głos T, Ziejka M, et al. A current insight into human knee menisci. Transl Res Anat 2023;32:100259. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Oliveira JM, Reis RL, editors. Regenerative Strategies for the Treatment of Knee Joint Disabilities. Studies in Mechanobiology, Tissue Engineering and Biomaterials. Vol. 21. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2017. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Krych AJ, Biant LC, Gomoll AH, Espregueira-Mendes J, Gobbi A, Nakamura N, editors. Cartilage Injury of the Knee: State-of-the-Art Treatment and Controversies. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2021. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Deckey DG, Tummala S, Verhey JT, Hassebrock JD, Dulle D, Miller MD, et al. Prevalence, biomechanics, and pathologies of the meniscofemoral ligaments: A systematic review. Arthrosc Sports Med Rehabil 2021;3:e2093-101. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Farr J, Gomoll AH, editors. Cartilage Restoration. Cham: Springer International Publishing; 2018. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Fairbank TJ. Knee joint changes after meniscectomy. J Bone Joint Surg Br 1948;30B:664-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Gillquist J, Oretorp N. Arthroscopic partial meniscectomy: Technique and long-term results. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1982;167:29-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Henning CE. Current status of meniscus salvage. Clin Sports Med 1990;9:567-76. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Musahl V, Citak M, O’Loughlin PF, Choi D, Bedi A, Pearle AD. The effect of medial versus lateral meniscectomy on the stability of the anterior cruciate ligament-deficient knee. Am J Sports Med 2010;38:1591-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Kim YS, Koo S, Kim JH, Tae J, Wang JH, Ahn JH, et al. Greater knee rotatory instability after posterior meniscocapsular injury versus anterolateral ligament injury: A proposed mechanism of high-grade pivot shift. Orthop J Sports Med 2023;11:23259671231188712. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Doral MN, Bilge O, Huri G, Turhan E, Verdonk R. Modern treatment of meniscal tears. EFORT Open Rev 2018;3:260-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Kim Y, Karl E, Ishijima M, Guy S, Jacquet C, Ollivier M. The potential of tendon autograft as meniscus substitution: Current concepts. J ISAKOS 2024;9:100353. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Novaretti JV, Patel NK, Lian J, Vaswani R, De Sa D, Getgood A, et al. Long-term survival analysis and outcomes of meniscal allograft transplantation with minimum 10-year follow-up: A systematic review. Arthroscopy 2019;35:659-67. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Seitz AM, Leiprecht J, Schwer J, Ignatius A, Reichel H, Kappe T. Autologous semitendinosus meniscus graft significantly improves knee joint kinematics and the tibiofemoral contact after complete lateral meniscectomy. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2023;31:2956-65. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]