The repair process of the pre-pubic aponeurotic complex (PPAC) may be enhanced by botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) infiltration.

Dr. Gian Nicola, Bisciotti , Via IV Novembre N° 46 Pontremoli 54027 (MS), Italy. bisciotti@libero.it

Introduction: Injuries of the pre-pubic aponeurotic complex (PPAC) are a significant cause of groin pain syndrome. These injuries tend to have limited self-healing capacity because the injured area is kept apart by opposing forces exerted by the rectus abdominis (RA) and adductor longus muscles. Recently, botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A) has been successfully used in a case report describing a patient with PPAC injuries. This study aims to evaluate the efficacy of BTX-A in a series of patients with PPAC injuries.

Materials and Methods: Ten male athletic subjects with PPAC injuries underwent infiltrative therapy with BTX-A at the level of the RA and adductor longus, followed by an 8-week rehabilitation program.

Results: Ultrasound assessment performed after the rehabilitation program showed that 9 subjects (90%) achieved complete restitutio ad integrum of the PPAC injury area, while 1 subject (10%) exhibited partial repair. At 12 months of follow-up, 9 patients (90%) returned to sports activity, 8 (80%) at the same level, and 1 (10%) at a lower level, but not due to residual pain. No adverse effects were recorded.

Conclusion: BTX-A infiltrative therapy appears to be a safe, effective, and promising treatment for PPAC injuries, enabling a quick return to sporting activity.

Keywords: Botulinum toxin, pre-pubic aponeurotic complex, groin pain syndrome.

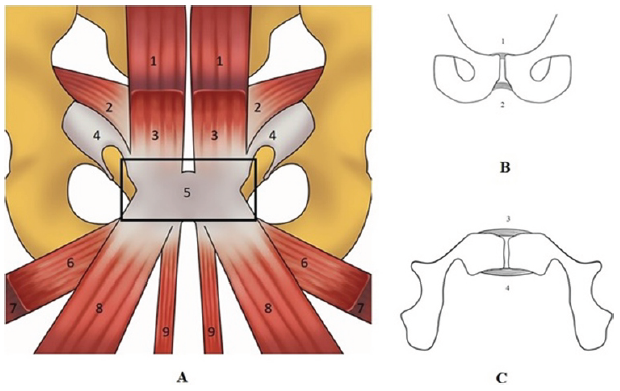

An important source of groin pain syndrome (GPS) is the injury to the pre-pubic aponeurotic complex (PPAC) [1,2]. The PPAC is a key anatomical structure of the pelvis, and a schematic representation is shown in Fig. 1.

Figure 1: A schematic view of the tendon structure forming the PPAC (box A) and a schematic view of the pubic ligaments in coronal view (box B) and axial view (box C). (a) (1) Rectus abdominis; (2) Transversus abdominis and internal oblique; (3) Pyramidalis; (4) External oblique; (5) Pre-pubic aponeurotic complex; (6) Pectineus; (7) Adductor brevis; (8) Adductor longus; (9) Gracilis. (b and c) (1) Superior pubic ligaments; (2) Inferior pubic ligament; (3) Anterior pubic ligament; (4) Posterior pubic ligament.

It is formed by the interconnection of the tendons of the adductor longus, adductor brevis, gracilis, and pectineus muscles; the aponeurosis of the rectus abdominis (RA), pyramidalis, and external oblique muscles; the articular disc; the anterior pubic periosteum; and the superior pubic ligaments (SPL), inferior pubic ligaments (IPL), and anterior pubic ligaments (APL). The posterior pubic ligament, however, is not considered part of the PPAC [2]. All three pubic ligaments (SPL, IPL, and APL) are connected to the articular disc [3]. Regarding the elastic properties of the symphyseal ligaments, the only ligament that may contain elastic fibers is the SPL [3]. From a biomechanical perspective, the PPAC exhibits intrinsic stiffness [4], and because it is subjected to significant mechanical stresses during athletic movements involving pelvic torsion, it also represents a biomechanical weak point [2]. In certain pathologies, such as femoroacetabular impingement (FAI), reduced hip joint mobility is compensated by hypermobility of the symphysis [5]. Consequently, FAI imposes high stress levels on the PPAC, particularly in the transverse plane [3], and it is no coincidence that FAI frequently appears in the etiopathogenesis of GPS [6]. Furthermore, the PPAC is subjected to upward tensile forces from the RA muscles and downward forces from the adductor muscles [4]. These opposing forces generate significant shear stresses [4], which can cause anatomical damage to the PPAC [4] and potentially trigger the onset of GPS.

The most frequent clinical situations involving PPAC injuries are represented by two different types of anatomical damage [4,6,7]: the first type is an injury of the PPAC afferent to the adductor longus tendon–RA–pyramidalis aponeurotic plate complex [1,4]; while the second type of injury is a PPAC avulsion from the anterior pubic bone [4,8].

PPAC injuries are visible on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) examination across all acquisition planes (axial, coronal, and sagittal) using classic fluid-sensitive sequences (T2 and STIR) and in PDFS and intermediate FS sequences. However, the oblique axial plane is particularly recommended [7]. Ultrasound (US) examination also appears to be a valid tool for diagnosing PPAC injuries [7]. PPAC injuries tend to have limited self-healing capacity because the injured area is kept apart by opposing forces exerted by the RA, in a superior–posterior direction, and the adductor longus (LA) in an inferior–anterior direction [9]. For this reason, conservative treatment often fails, and persistent PPAC injury can lead to the development of a long-standing GPS [10,11]. Recently, Botulinum toxin type A (BTX-A), a neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium Clostridium botulinum, has been successfully used to improve outcomes in flexor tendon repair [12,13] and in cases of long-standing adductor-related groin pain [14]. Based on this, the present study hypothesizes that BTX-A may promote the repair of the aponeurotic tissue forming the PPAC. To the best of our knowledge, since only one case report on this topic exists in the literature [11], this is the first case series describing the use of BTX-A in PPAC injuries.

This study evaluated the efficacy of BTX-A injection in a cohort of athletes with PPAC lesions, conducted between June 2023 and April 2024. This study was approved by the Institutional Ethic Committee (IEC approval number /2023/006 dated April 10th, 2023).

Subjects

In this case series, ten male athletes were included. Their mean age was 25.3 ± 6.8 years, with an average weight of 78.7 ± 3.4 kg and height of 177.8 ± 8.2 cm. All participants had PPAC lesions diagnosed through both MRI and US, with findings corroborated by clinical symptoms and signs.

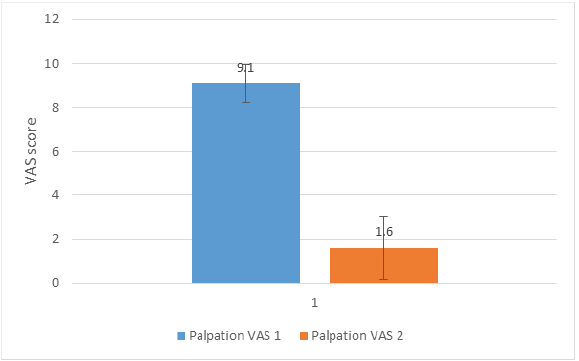

The subjects reported symptoms interfering with their sporting activities for an average duration of 18.3 ± 3.4 months. All subjects had failed conservative treatment modalities. No patient presented with other concomitant pathologies that could account for GPS. Due to persistent pain, all patients had ceased their sporting activities. The level of athletic activity was classified as follows: professional if training sessions exceeded four per week (including competitions), semi-professional if exactly four sessions per week, and amateur if fewer than three sessions per week [2]. The specific sports practiced and their levels are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1: The sports activities practiced by the considered subjects and their level of practice

Imaging

All subjects underwent pelvic MRI and US examination following a standardized protocol [7]. On MRI, PPAC injuries appeared as hyperintense signal zones on fluid-sensitive sequences (T2 and STIR), propagating unilaterally or bilaterally from the PPAC midline [7]. Conversely, US examination revealed PPAC injuries as hypoechoic areas [7]. At MRI and US assessment, six subjects (60%) exhibited bilateral avulsion of the PPAC from the anterior pubic bone [4,8], while two subjects (20%) showed injury of the PPAC afferent to the adductor longus tendon–RA–pyramidalis aponeurotic complex on the right, and two subjects (20%) on the left [1,4]. The diagnosis of PPAC injury was established when radiological findings were consistent with clinical symptoms and signs [2].

Medical treatment

Exclusion criteria for BTX-A infiltrative therapy included [15,16]:

- Ongoing anticoagulant therapy

- Muscular disorders (e.g., myopathies, polymyositis)

- Deep venous thrombosis

- Treatment with BTX-A within the previous 6 months.

Once these exclusion criteria were confirmed absent, the infiltrative procedure was performed. An experienced interventional radiologist (15 years in musculoskeletal interventions) conducted US-guided BTX-A injections using a Terason USmart 3200 scanner (Teratech, 77 Terrace Hall Ave., Burlington, MA 01803) equipped with a 12-5 MHz high-resolution linear broadband transducer. A 22-gauge hypodermic needle (2.5–4 cm in length) was used to deliver a total of 250 units of BTX-A for each treated muscle (Dysport® 500 units, C. botulinum type A toxin-hemagglutinin complex) in three discrete injections into the axial plane of the proximal, medial, and distal portions of the left and right LA and RA muscles bellies [17]. The toxin was reconstituted to a concentration of 100 U/mL. Injections were performed only when the needle was correctly positioned in the proximal, middle, and distal thirds of each muscle. Bilateral injections were performed if the PPAC injury was bilateral (6 subjects, 60%), or in the right RA and LA (2 subjects, 20%), and in the left RA and LA if the injury was unilateral (2 subjects, 20%) [16]. Since BTX-A acts directly at the neuromuscular junction, it was unnecessary to locate the muscle’s motor points [18].

All patients followed a standardized, supervised 8-week rehabilitation program.

Outcome evaluation

At the conclusion of the 8-week rehabilitation program, all patients underwent a subsequent clinical examination and a follow-up US assessment. Both the clinical assessments and US examinations were performed by the same clinical team and the same radiologist to ensure consistency. During the two clinical assessment sessions, the following tests were conducted [19]:

- Palpation test of the injury area performed under US guidance

- Squeeze test 1

- Squeeze test 2.

The Squeeze tests differed in the resistance arm position. In Squeeze test 1, the resistance arm was positioned at knee level, whereas in Squeeze test 2, it was positioned at ankle level [19].

For each test, the patient was asked to rate their perceived pain using a Visual Analog Scale (VAS). The recorded values included:

- VAS score during palpation test pre-intervention (Palpation VAS 1) and at the end of the rehabilitation period (Palpation VAS 2)

- VAS score during Squeeze test 1 pre-intervention and post-rehabilitation

- VAS score during Squeeze test 2 pre-intervention and post-rehabilitation.

At the 12-month follow-up, each patient was asked to complete a questionnaire comprising the following items:

- Completion of the Clinical Global Impression Scale [20]

- Dichotomous response (yes/no) regarding achievement of return to play (RTP)

- If RTP was achieved, the RTP level was specified (i.e., at pre-injury level or at a lower level due to residual pain)

- Patients rated their perceived pain during sports activity pre-intervention on a VAS scale (sport VAS pre-intervention), and the same assessment was repeated at 12 months’ post-intervention (Sport VAS at follow-up) [21]

- Dichotomous response (yes/no) regarding satisfaction with the medical procedure received.

Any adverse effects observed following BTX-A injection were also documented.

Statistical analysis

Results were analyzed both quantitatively and qualitatively. Quantitative data were summarized using descriptive statistics, including means and standard deviations, while qualitative data were expressed as absolute and relative frequencies. The significance of differences between pre- and post-intervention values – specifically: Sport VAS scores, Palpation test VAS, and Squeeze test VAS (tests 1 and 2) – was evaluated using the Wilcoxon-Mann–Whitney test. The strength of associations between these variables was assessed by calculating effect sizes. A P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

US assessment performed after the 8-week rehabilitation program showed that 9 subjects (90%) achieved complete restitution ad integrum of the PPAC injury area, while 1 subject (10%) exhibited partial repair.

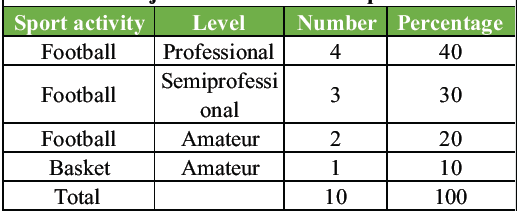

The Palpation VAS 1 and Palpation VAS 2 scores were 9.1 ± 0.88 and 1.6 ± 1.43, respectively. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01), with a Cohen’s d of 6.31. A graphical representation of the results is shown in Fig. 2.

Figure 2: Graphical representation of the result for the Palpation Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) 1 and Palpation VAS 2. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01), with a Cohen’s d of 6.31.

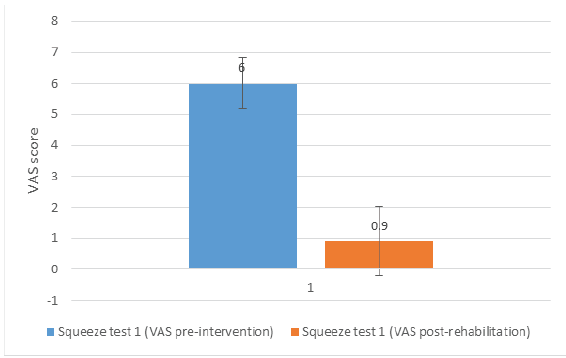

The VAS scores for Squeeze Test 1 pre-intervention and post-rehabilitation were 6.0 ± 0.82 and 0.9 ± 1.20, respectively (P < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 4.96). A graphical representation of the results is shown in Fig. 3.

Figure 3: Graphical representation of the result for Squeeze Test 1 pre-intervention and Squeeze Test 1 post-rehabilitation. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) with a Cohen’s d of 4.96.

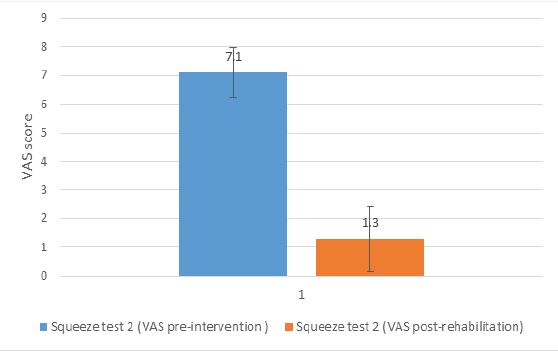

For Squeeze Test 2, pre-intervention and post-rehabilitation scores were 7.1 ± 0.88 and 1.3 ± 1.49, respectively (P < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 4.74). A graphical representation of the results is shown in Fig. 4.

Figure 4: Graphical representation of the result for Squeeze Test 2 pre-intervention and Squeeze Test 2 post-rehabilitation. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) with a Cohen’s d of 4.74.

Based on US and clinical assessments, 9 subjects (90%) were cleared for RTP. One subject (10%) was not cleared and chose to discontinue the rehabilitation program.

The Clinical Global Impression Scale [20] results indicated: very much improved in 4 subjects (40%), much improved in 5 subjects (50%), and minimally improved in 1 subject (10%).

Of the 9 patients (90%) who achieved RTP, 8 (80%) returned at the same level, while 1 (10%) returned at a lower level, not due to residual pain.

One subject (10%) was unable to return to amateur football and chose to engage in other sports, which did not provoke pain.

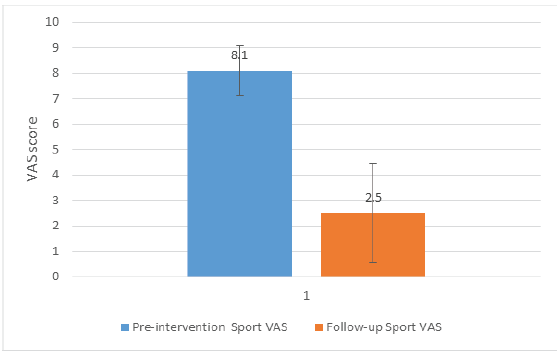

Pre-intervention and follow-up sport VAS scores were 8.10 ± 0.99 and 2.50 ± 1.96, respectively (P < 0.01; Cohen’s d = 3.60). A graphical representation of the results is shown in Fig. 5.

Figure 5: Graphical representation of the result for Pre-intervention Sport Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) and follow-up Sport VAS. The difference was statistically significant (P < 0.01) with a Cohen’s d equal to 3.60.

Nine patients (90%) expressed satisfaction with the procedure and would repeat the treatment; one patient (10%) was minimally satisfied but would still undergo the procedure again.

No adverse effects related to BTX-A injections were recorded.

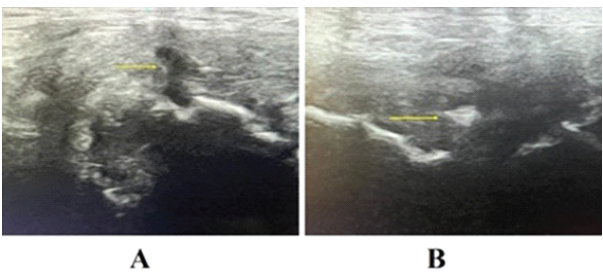

All subjects included in this study were treated with BTX-A infiltration at the level of the LA and RA, unilaterally or bilaterally, depending on the type of PPAC lesion observed. After an 8-week rehabilitation program, 90% of the treated subjects demonstrated, upon US assessment, complete anatomical healing of the PPAC injury (restitutio ad integrum). An example of the healing process observed in US is shown in Fig. 6.

Figure 6: US assessment of the healing process of a prepubic aponeurotic complex lesion. (a) shows the original lesion in longitudinal view before medical treatment (arrow). (b) shows the same lesion in axial view observed 4 weeks after medical treatment, showing signs of advanced healing (arrow).

Furthermore, all clinical tests performed before infiltration therapy and after the 8-week rehabilitation period showed a statistically significant reduction in pain, as measured by the VAS (all P < 0.01; Cohen’s d values ranged from 3.60 to 6.31). Only one subject, at the 8-week follow-up, exhibited on US examination a lesion area that was not yet fully healed and presented a moderately severe clinical condition. For this subject, the scores for Palpation VAS 1, Squeeze test 1, and Squeeze test 2 recorded after rehabilitation were 5, 4, and 5, respectively, whereas during pre-intervention assessment, these values were 10.7 and 8. Accordingly, based on clinical and US evaluations, this subject was not cleared for RTP and was proposed an extension of rehabilitation for an additional 4 weeks. However, the subject declined this proposal and opted to attempt RTP nonetheless. Following BTX-A infiltration and the 8-week rehabilitation program, 9 out of 10 subjects (90%) received approval for RTP. At a 12-month follow-up, 8 subjects (80%) had returned to their previous level of sporting activity, while one subject (10%) resumed activity at a lower level (not due to residual pain). The subject, who was not cleared for RTP, was unable to return to amateur football, chose to engage in other sports such as cycling and running, which did not provoke pain. Nine subjects (90%) expressed satisfaction with the treatment and indicated they would repeat the same therapeutic approach, while one subject (10%) was minimally satisfied but would still undergo the procedure again. No adverse effects related to BTX-A injections were recorded at the 12-month follow-up. These findings support the efficacy of BTX-A infiltrations at the LA and RA levels in treating PPAC lesions in athletes.

Anatomical and pathophysiological considerations

It is important to recognize that the PPAC represents an area of inherent anatomical weakness, particularly during athletic movements involving pelvic torsion and single-leg stance manoeuvres [2]. Since the PPAC is formed by interconnected structures with differing force vectors, it is subjected to traction from antagonistic forces (Fig. 2) [4]. The intrinsic elasticity of the PPAC is attributable solely to the modest amount of elastic fibers present in the SPL [22], whereas the APL and IPL appear to lack elastic fibers altogether [22]. Consequently, given the limited elastic tissue content, the PPAC can be considered an intrinsically rigid anatomical structure [22]. This rigidity, combined with the significant shear forces exerted during athletic activities, may lead to injuries of the PPAC afferent to the adductor longus tendon–RA–pyramidalis aponeurotic plate complex and/or PPAC avulsion injuries (i.e., separation of the PPAC from the pubic bone [2,23]. Such injuries may be acute or result from overuse [2,23]. PPAC lesions also demonstrate an inherent resistance to biological repair, as the opposing mechanical tensions – primarily from the RA and LA – limit the complex’s capacity for self-healing [7,18].

Mechanism and pharmacology of BTX-A

The BTX is a neurotoxic protein produced by the bacterium C. botulinum and related species. To date, seven serotypes of BTX have been identified and alphabetically labeled from A to G. All of the serotypes show a similar chemical structure and, except for the C2 subtype, are neurotoxic [24]. BTX causes a temporary dose-related weakness, paresis, or paralysis of skeletal muscle by blocking the release of acetylcholine at the neuromuscular junction. The toxin starts to take effect within 2–3 days, and the maximal effect is achieved after about 2 weeks. These effects last for an average of 12–16 weeks after which, the motor end plates recover completely and the neurotransmission mechanism restarts [24]. It is important to underline that BTX, when inoculated, has the ability to directly reach the neuro-muscular junction. Therefore, this characteristic allows the clinician to perform the inoculation without necessarily having to search for the muscle motor point [16,18]. Furthermore, BTX possesses limited adverse effects as it presents a good safety profile. The most important adverse effect is the unintentional diffusion into adjacent anatomical sites, which may cause weakness in and around the target area. Other rare systemic adverse effects may include allergic reactions, generalized weakness, and influenza-like symptoms. BTX must be used with caution in patients with existing paresis, such as myasthenia gravis, Lambert–Eaton syndrome, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and other types of myopathies or motor neuropathy [18]. Furthermore, it should be remembered that in the literature there are 5 studies reporting venous thrombosis after BTX-A infiltration therapy [15, 25–28]. There are several studies in the literature on the use of BTX-A in improving the outcome of flexor tendon repair [12,13,29]. In these cases, the chemical denervation process induced by BTX is used to partially weaken the flexor muscles and decrease their traction force on the tendons. This decrease in tendon tension could facilitate the processes of tendon repair [11,12,13,29]. BTX is also used, with the same rationale, in abdominal wall hernia repair [30]. Indeed, during abdominal wall hernia repair, the linea alba is reapproximated bilaterally and needs time to remodel and tie together. In inducing lateral paralysis BTX enables the linea alba to heal by eluding, for a substantial period of time, the constant forces of lateral traction. This decreases both hernia recurrence and separation of the re-approximated linea alba [30]. The use of BTX in PPAC injuries is based on these same physiological principles. In the case of PPAC injuries, BTX may decrease the tension of the LA and RA to the point of favouring PPAC repair. Another important advantage of BTX is its ability to modulate pain by inhibiting substance P and calcitonin gene-related peptide [31].

Limitation of the study and future directions

The main limitations of this study are that it is a monocentric retrospective study. Furthermore, the small sample size limited the statistical power of the analysis. Therefore, future studies involving larger populations would be desirable.

BTX-A infiltrative therapy may represent a new and promising treatment for PPAC lesions. However, there is a lack of specific studies in the scientific literature on the use of BTX-A in PPAC injuries. Consequently, it would be beneficial to develop study protocols – preferably randomized controlled trials – t hat focus on assessing the use of BTX-A in the promising approach of treating PPAC lesions.

PPAC lesions tend to have an intrinsic resistance to biological repair; therefore, the outcomes of traditional conservative treatments may be unsatisfactory. The infiltrative BTX-A therapy proposed in this case series may offer a new and promising treatment option for PPAC lesions.

References

- 1. Matsuda DK, Matsuda NA, Head R, Tivorsak T. Endoscopic rectus abdominis and prepubic aponeurosis repairs for treatment of athletic Pubalgia. Arthrosc Tech 2017;6:e183-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Bisciotti A, Bisciotti GN, Eirale C, Bisciotti A, Auci A, Bona S, et al. Prepubic aponeurotic complex injuries: A structured narrative review. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2022;62:1219-27. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Mathieu T, Van Glabbeek F, Van Nassauw L, Van Den Plas K, Denteneer L, Stassijns G. New insights into the musculotendinous and ligamentous attachments at the pubic symphysis: A systematic review. Ann Anat 2022;244:151959. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Pieroh P, Li ZL, Kawata S, Ogawa Y, Josten C, Steinke H, et al. The topography and morphometrics of the pubic ligaments. Ann Anat 2021;236:151698. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Bisciotti GN, Di Marzo F, Auci A, Parra F, Cassaghi G, Corsini A, et al. Cam morphology and inguinal pathologies: Is there a possible connection? J Orthop Traumatol 2017;18:439-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Omar IM, Zoga AC, Kavanagh EC, Koulouris G, Bergin D, Gopez AG, et al. Athletic pubalgia and “sports hernia”: Optimal MR imaging technique and findings. Radiographics 2008;28:1415-38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Bisciotti GN, Di Pietto F, Rusconi G, Bisciotti A, Auci A, Zappia M, et al. The role of MRI in groin pain syndrome in athletes. Diagnostics (Basel) 2024;14:814. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Brennan D, O’Connell MJ, Ryan M, Cunningham P, Taylor D, Cronin C, et al. Secondary cleft sign as a marker of injury in athletes with groin pain: MR image appearance and interpretation. Radiology 2005;235:162-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Mullens FE, Zoga AC, Morrison WB, Meyers WC. Review of MRI technique and imaging findings in athletic Pubalgia and the “sports hernia”. Eur J Radiol 2012;81:3780-92. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Bisciotti GN, Zini R, Aluigi M, Aprato A, Auci A, Bellinzona E, et al. Groin pain syndrome Italian consensus conference update 2023. J Sports Med Phys Fitness 2024;64:402-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Bisciotti GN, Alessio A, Bisciotti A, Bisciotti A. The use of botulinum toxin in pre-pubic aponeurotic complex injuries: A case report. J Orthop Case Rep 2024;14:60-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. De Aguiar G, Chait LA, Schultz D, Bleloch S, Theron A, Snijman CN, et al. Chemoprotection of flexor tendon repairs using botulinum toxin. Plast Reconstr Surg 2009;124:201-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Khalil LS, Keller RA, Mehran N, Marshall NE, Okoroha K, Frisch NB, et al. The utility of botulinum toxin A in the repair of distal biceps tendon ruptures. Musculoskelet Surg 2018;102:159-63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Creuzé A, Fok-Cheong T, Weir A, Bordes P, Reboul G, Glize B, et al. Novel use of botulinum toxin in long-standing adductor-related groin pain: A case series. Clin J Sport Med 2022;32:567-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Mines ML, Pacheco T, Castel-Lacana E, de Boissezon X, Marque P, Montastruc F. Venous thrombosis after botulinum therapy in lower limb: A case report and literature review. Ann Phys Rehabil Med 2019;62:457-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Dressler D, Altavista MC, Altenmueller E, Bhidayasiri R, Bohlega S, Chana P, et al. Consensus guidelines for botulinum toxin therapy: General algorithms and dosing tables for dystonia and spasticity. J Neural Transm (Vienna) 2021;128:321-35. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Wissel J, Ward AB, Erztgaard P, Bensmail D, Hecht MJ, Lejeune TM, et al. European consensus table on the use of botulinum toxin type A in adult spasticity. J Rehabil Med 2009;41:13-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Ramirez-Castaneda J, Jankovic J, Comella C, Dashtipour K, Fernandez HH, Mari Z. Diffusion, spread, and migration of botulinum toxin. Mov Disord 2013;28:1775-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Bisciotti GN, Volpi P, Zini R, Auci A, Aprato A, Belli A, et al. Groin Pain Syndrome Italian Consensus Conference on terminology, clinical evaluation and imaging assessment in groin pain in athlete. BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2016;2:e000142. Erratum in: BMJ Open Sport Exerc Med 2017;2:e000142corr1. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Forkmann T, Scherer A, Boecker M, Pawelzik M, Jostes R, Gauggel S. The Clinical Global Impression Scale and the influence of patient or staff perspective on outcome. BMC Psychiatry 2011;11:83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Price DD, McGrath PA, Rafii A, Buckingham B. The validation of visual analogue scales as ratio scale measures for chronic and experimental pain. Pain 1983;17:45-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Becker I, Woodley SJ, Stringer MD. The adult human pubic symphysis: A systematic review. J Anat 2010;217:475-87. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Schilders E, Bharam S, Golan E, Dimitrakopoulou A, Mitchell A, Spaepen M, et al. The pyramidalis-anterior pubic ligament-adductor longus complex (PLAC) and its role with adductor injuries: A new anatomical concept. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:3969-77. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Henkel JS, Jacobson M, Tepp W, Pier C, Johnson EA, Barbieri JT. Catalytic properties of botulinum neurotoxin subtypes A3 and A4. Biochemistry 2009;48:2522-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Jost WH, Schanne S, Mlitz H, Schimrigk K. Perianal thrombosis following injection therapy into the external anal sphincter using botulin toxin. Dis Colon Rectum 1995;38:781. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Fernández López F, Conde Freire R, Rios Rios A, García Iglesias J, Caínzos Fernández M, Potel Lesquereux J. Botulinum toxin for the treatment of anal fissure. Dig Surg 1999;16:515-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Skaf GS, Domloj NT, Salameh JA, Atiyeh B. Pseudoaneurysm of the superficial temporal artery: A complication of botulinum toxin injection. Aesthetic Plast Surg 2012;36:982-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Pisani LR, Bramanti P, Calabro RS. A case of thrombosis of subcutaneous anterior chest veins (Mondor’s disease) as an unusual complication of botulinum type A injection. Blood Coagul Fibrinolysis 2015;26:685-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Tüzüner S, Balci N, Ozkaynak S. Results of zone II flexor tendon repair in children younger than age 6 years: Botulinum toxin type A administration eased cooperation during the rehabilitation and improved outcome. J Pediatr Orthop 2004;24:629-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Zielinski MD, Kuntz M, Zhang X, Zagar AE, Khasawneh MA, Zendejas B, et al. Botulinum toxin A-induced paralysis of the lateral abdominal wall after damage-control laparotomy: A multi-institutional, prospective, randomized, placebo-controlled pilot study. J Trauma Acute Care Surg 2016;80:237-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Durham PL, Cady R, Cady R. Regulation of calcitonin gene-related peptide secretion from trigeminal nerve cells by botulinum toxin type A: implications for migraine therapy. Headache 2004;44:35-42; discussion 42-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]