From 1999 to 2019, RA mortality declined, but rates rose again in 2020, likely due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Women, older adults, and Native Americans had the highest mortality, with persistent racial and geographic disparities, especially in rural areas.

Dr. Aamir Shahzad, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust, Manchester OL, United Kingdom. E-mail: amirshehzad4321@gmail.com

Introduction: Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic inflammatory disease associated with systemic complications and increased mortality risk. Advances in RA treatment (early aggressive therapy, biologics) since the late 1990s have improved disease control and were expected to reduce mortality. We analyzed national trends in RA-related mortality from 1999 to 2020 to assess overall changes and disparities by sex, age, race/ethnicity, region, and urbanicity in the United States.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a retrospective time-trend analysis using the cause of death WONDER multiple-cause-of-death database. Deaths among U.S. residents aged ≥25 years with RA as the underlying cause (ICD-10 codes M05.x, M06.x, M08.0) from 1999 to 2020 were extracted. Age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR) per 100,000 (2000 US standard population) were calculated overall and stratified by sex, age group, race/ethnicity, census region, and metropolitan versus nonmetropolitan residence. Joinpoint regression was used to evaluate changes in trends and estimate annual percent change (APC).

Results: A total of 210,156 RA-related deaths occurred from 1999 to 2020. The AAMR declined from 5.65/100,000 in 1999 to a nadir of 3.33 in 2019 – an average annual decrease of about –2% to –3%, but then rose to 4.07 in 2020. Female patients had higher RA mortality than males throughout (2020 AAMR 5.31 vs. 2.51). Both sexes experienced significant mortality declines through 2018 (female APC –2.4%; male APC –3.0% overall), followed by a sharp increase in 2018–2020 (female APC +9.1%; male +6.3%). By age, the 65+ years group accounted for the vast majority of RA deaths and saw the largest absolute decline (AAPC –2.1%), whereas younger age groups had lower rates and smaller or no improvements. RA mortality fell across all major racial/ethnic groups except American Indians/Alaska Natives. In 2018, non-Hispanic White AAMR dropped to ~3.2, Black ~2.8, Hispanic ~2.7, and Asian/Pacific Islander ~1.8, while Native American rates remained high (~8+). A significant rebound in 2020 was observed, especially among Black and Hispanic populations. Regionally, the Midwest and West had the highest RA mortality and the Northeast the lowest, but all regions showed parallel downward trends through 2018 (each APC ~–2.6% to –2.9%) with an upward inflection in 2020. RA mortality in non-metropolitan (rural) areas was consistently higher than in metropolitan areas (e.g., 2020 AAMR 5.3 vs. 3.8), despite similar relative declines pre-2018 and increases in 2020 (rural APC +9.9% vs. urban +8.8% for 2018–2020). Objectives: To evaluate national trends and demographic disparities in rheumatoid arthritis–related mortality in the United States from 1999 to 2020 by sex, age, race/ethnicity, region, and urbanicity.

Conclusion: From 1999 to 2019, U.S. RA mortality rates significantly decreased, likely reflecting improved RA treatments and cardiovascular risk management. These gains, however, were not shared equally; Native Americans and rural residents had persistently higher mortality and less improvement. Alarmingly, RA mortality rose in 2020, coinciding with the COVID-19 pandemic, which may have disproportionately affected RA patients. Ongoing efforts are needed to understand and address the recent increase and to close persistent demographic gaps in RA outcomes.

Keywords: Rheumatoid arthritis, mortality, epidemiology, trends, health disparities, United States.

Rheumatoid arthritis (RA) is a chronic, systemic autoimmune disease affecting roughly 0.5–1.0% of U.S. adults and driving substantial disability and healthcare use [1]. Beyond synovitis and joint destruction, extra-articular involvement, particularly cardiovascular (CV) and pulmonary disease, contributes materially to excess mortality [2]. Historically, people with RA experienced ~1.5–2.0-fold higher all-cause mortality than the general population, with CV disease and serious infections accounting for a large share of deaths, reflecting both systemic inflammation and treatment-related immunosuppression [2,3].

Over the past two decades, earlier diagnosis, treat-to-target strategies, and the widespread use of conventional, biologic, and targeted synthetic DMARDs have transformed RA care, improving disease control and functional outcomes [4]. Population-based studies suggest that survival has improved in the modern treatment era, narrowing the historical mortality gap, particularly among incident RA cohorts diagnosed after 2000 [5]. Nevertheless, the benefits have not been uniform. Persistent disparities are reported by sex (higher absolute mortality in women due to greater disease burden), race/ethnicity, geography, and socioeconomic context [1,6]. Of particular concern, American Indian/Alaska Native (AI/AN) populations bear the highest RA mortality in the United States, with limited improvement over time and a disproportionate share of deaths at younger ages, likely reflecting structural barriers to specialty care, comorbidity profiles, and social determinants of health [6]. Geographic and urbanicity gradients also persist, with rural residents experiencing higher RA mortality than metropolitan counterparts, plausibly due to differential access to rheumatology services, delayed diagnosis, and challenges in delivering advanced therapies [7].

The COVID-19 pandemic introduced additional risks for patients with immune-mediated diseases. Meta-analytic evidence indicates that RA is associated with higher odds of severe COVID-19 and death compared with the general population, with risk concentrated among older adults and those receiving glucocorticoids or with high inflammatory activity [8]. These dynamics raise the possibility that national declines in RA mortality may have plateaued or reversed during the pandemic period.

Against this background, we used cause of death (CDC) WONDER vital statistics to characterize long-term U.S. trends in RA age-adjusted mortality rates (AAMR) from 1999 to 2020, overall and stratified by sex, age, race/ethnicity, census region, and metropolitan status. We hypothesized sustained declines through the pre-pandemic era with heterogeneity by subgroup, and a potential inflection coincident with 2020, highlighting opportunities to target persistent inequities and pandemic-related vulnerabilities.

Rheumatoid arthritis is associated with excess mortality, but the extent to which modern therapies and improved comorbidity management have translated into population-level survival gains—and whether these benefits are shared equitably across demographic and geographic groups—remains unclear. A nationwide, long-term analysis of RA mortality trends and disparities is needed to quantify progress, identify high-risk populations, and understand the impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on these trajectories.

Study design and data source

Study Design

This was a retrospective, population-based time-trend study using publicly available mortality data from the CDC. Death certificate records for all U.S. residents aged ≥25 years with rheumatoid arthritis listed as the underlying cause of death (ICD-10 M05.x, M06.x, M08.0) between 1999 and 2020 were obtained from the CDC WONDER Multiple Cause of Death online database. Because the database contains all registered deaths in the United States that meet these criteria, no a priori sample size calculation was performed; the study sample comprised the entire eligible population of RA-related deaths during the study period. Accordingly, no sampling technique was used—this was effectively a census of all RA-related deaths captured in the national CDC mortality registry and extracted by the research team via the free CDC WONDER query interface. The study followed STROBE reporting principles, and was exempt from IRB review.

Case definition and coding

Underlying-cause deaths were identified with ICD-10 codes M05.0–M05.9 (seropositive RA), M06.0–M06.9 (other/seronegative RA), and M08.0 (juvenile RA). Although M08.0 captures juvenile disease, RA deaths occur overwhelmingly in adults; inclusion ensured comprehensive capture of RA-coded underlying deaths.

Participants and stratifications

The analytic cohort comprised decedents aged ≥25 years with RA coded as the underlying cause between January 1, 1999, and December 31, 2020. Demographic attributes (from death certificates) included sex (female, male), age groups (25–44, 45–64, ≥65 years), race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, non-Hispanic AI/AN, non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander, Hispanic), U.S. Census region (Northeast, Midwest, South, West), and urbanization (metropolitan vs. non-metropolitan per CDC/USDA classifications). Annual counts and corresponding population denominators supported rate calculations in each stratum.

Outcome and time horizon

The primary endpoint was AAMR/100,000 (direct age adjustment to the 2000 U.S. standard population), overall and by subgroup. Crude mortality rates and total annual RA death counts were summarized for context. The a priori focus included long-term patterns and potential trend inflections in 2018–2020, coincident with the first pandemic year (2020).

Statistical analysis

We described annual RA death counts and AAMR overall and within strata, visualized temporal trends (Fig. 1, 2, 3, 4, 5), and applied Joinpoint regression (log-linear models; permutation tests) to detect statistically significant changes in slope (“joinpoints”).

For each segment, we estimated annual percent change (APC) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs); over the full 1999–2020 interval, we reported Average APC (AAPC). Statistical significance was defined as two-sided P < 0.05. Comparisons between demographic strata were qualitative and based on non-overlap of CIs. Data handling and figure generation used the Joinpoint software and Microsoft Excel. All analyses were ecological/population-level; no individual-level longitudinal data were available.

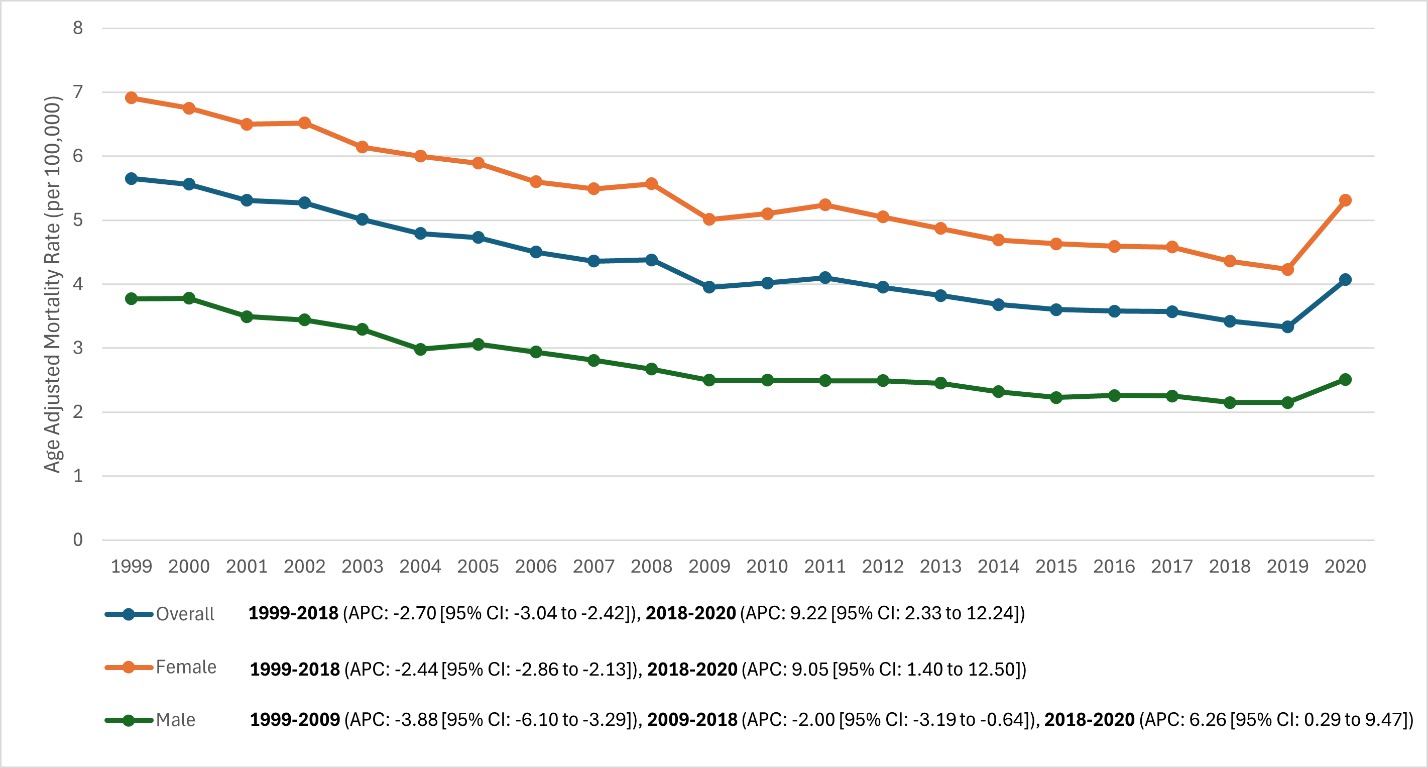

Overall trend (Fig. 1): From 1999 to 2019, U.S. age-adjusted mortality from RA declined steadily, then rose in 2020. The overall AAMR fell from 5.65/100,000 in 1999 (10,015 deaths) to a nadir of 3.33 in 2019 (8,864 deaths), a 41% reduction. In 2020, AAMR increased to 4.07 (11,018 deaths), reversing roughly a decade of prior gains while remaining below late-1990s levels. Joinpoint regression identified a joinpoint at 2018: AAMR declined –2.70%/year (95% CI –3.1 to –2.4; P < 0.001) during 1999–2018, then increased +9.22%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.011). The overall 1999–2020 AAPC was –1.7% (95% CI –2.3 to –1.5; P < 0.001), masking the late uptick.

Sex differences (Fig. 1): Women consistently had higher RA mortality than men (≈2:1). Female AAMR: 6.91 (1999) to 4.23 (2019) to 5.31 (2020). Male AAMR: 3.77 (1999) to 2.15 (2019) to 2.51 (2020). Female trend: joinpoint at 2018; –2.44%/year (1999–2018; P < 0.001) then +9.05%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.018). Male trend: joinpoints at 2009 and 2018; –3.88%/year (1999–2009; P = 0.004), –2.00%/year (2009–2018; P = 0.013), then +6.26%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.040). Men realized larger proportional improvements pre-2018, but the absolute female predominance persisted, and both sexes rose in 2020.

Figure 1: Overall and sex-stratified trends in age-adjusted mortality rates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in the United States, 1999–2020 (Line graph depicting the decline in RA mortality for the total population, females, and males over time, with a noticeable increase in all groups in 2020).

Figure 1: Overall and sex-stratified trends in age-adjusted mortality rates in patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA) in the United States, 1999–2020 (Line graph depicting the decline in RA mortality for the total population, females, and males over time, with a noticeable increase in all groups in 2020).

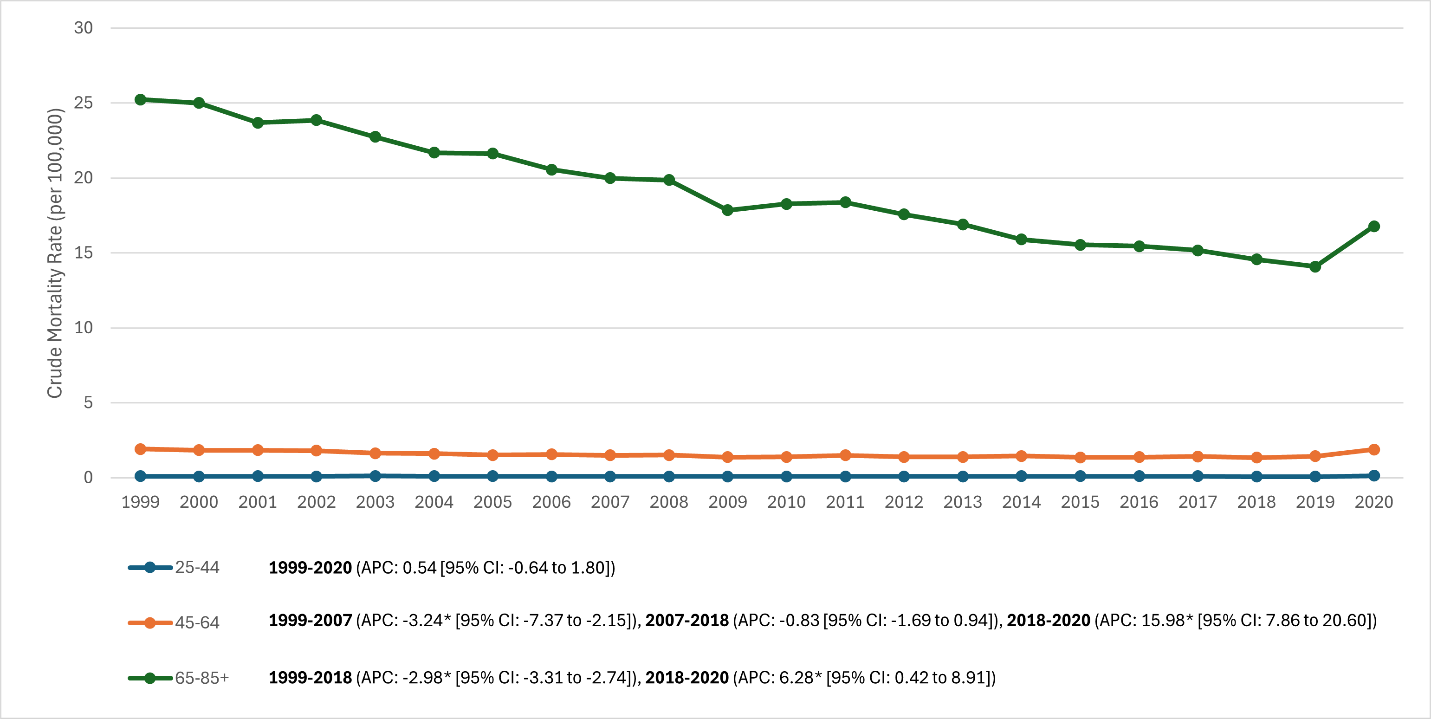

Age groups (Fig. 2): Mortality increased sharply with age and was lowest in young adults. In 2020, crude RA mortality was 0.14 (25–44), 1.9 (45–64), and 16.8 (≥65)/100,000. The ≥65 group drove national trends, declining from ~29 (1999) to ~18 (2018), then rising to ~17.7 (2020) from ~16.0 (2019). Joinpoint in ≥65 at 2018: –2.98%/year (1999–2018; P < 0.001) then +6.28%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.038). Ages 45–64 declined from ~5.5 (1999) to ~2.2 (2014–2015), plateaued (~2.1) through 2019, and rose to ~2.7 in 2020; join points: –3.24%/year (1999–2007; P = 0.005), ~flat (2007–2018; P = 0.20), then +15.98%/year (2018–2020; P < 0.001). Ages 25–44 remained <0.2 throughout with no significant trend (APC +0.54%/year; P = 0.32); small counts limit precision.

Figure 2: Age group-stratified trends in rheumatoid arthritis mortality (crude mortality rates) in the United States, 1999–2020 (Line graph showing rheumatoid arthritis mortality separated by ages 25–44, 45–64, and ≥65. The ≥65 group has the highest curve with a marked downward trend until an uptick at the end; the 45–64 group shows a moderate decline that plateaus, then rises sharply at the end; the 25–44 group remains near-flat at the bottom).

Figure 2: Age group-stratified trends in rheumatoid arthritis mortality (crude mortality rates) in the United States, 1999–2020 (Line graph showing rheumatoid arthritis mortality separated by ages 25–44, 45–64, and ≥65. The ≥65 group has the highest curve with a marked downward trend until an uptick at the end; the 45–64 group shows a moderate decline that plateaus, then rises sharply at the end; the 25–44 group remains near-flat at the bottom).

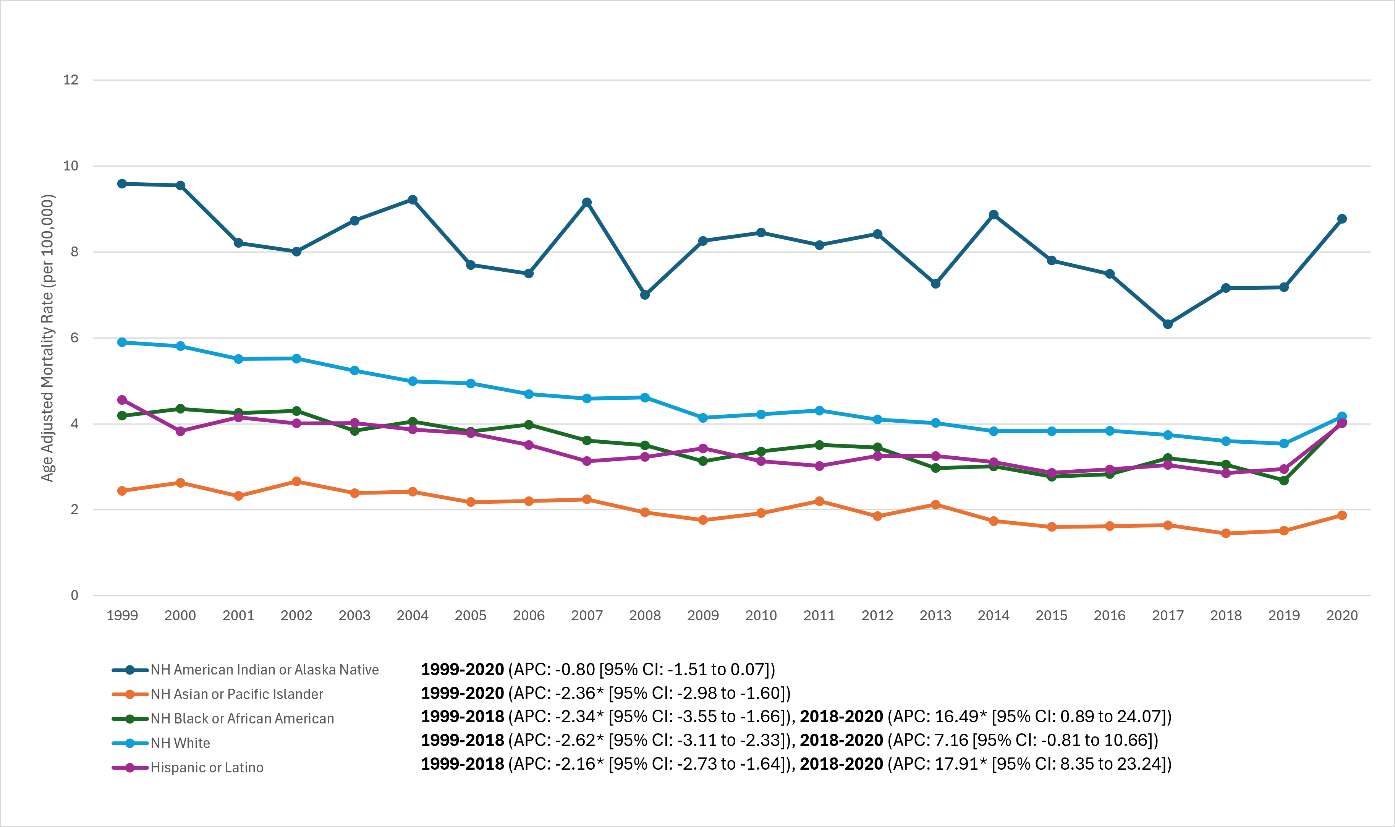

Race/ethnicity (Fig. 3). Pronounced, persistent disparities were observed. Rank order of AAMR burden in 2020: AI/AN >> White ≈ Black ≈ Hispanic >> Asian.

- AI/AN: Highest mortality across all years; ~6 (1999) and 8.77 (2020), with no significant long-term decline (APC –0.8%/year; P = 0.07). By 2020, AI/AN rates were ~2× White rates (8.8 vs. 4.2) and >4× Asian rates. A substantial share of AI/AN RA deaths occurred <65 years, indicating premature mortality.

- Non-Hispanic white:90 (1999) to 3.20 (2018) to 4.17 (2020). Joinpoint mirrors overall trend: –2.62%/year (1999–2018; P < 0.001), then +7.16%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.08). Net AAPC –1.73% (P < 0.001).

- Non-Hispanic black:19 (1999) declining to ~2.3 (2018), then rising to 4.05 (2020). Joinpoint: –2.34%/year (1999–2018; P = 0.007) followed by +16.5%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.034). Net AAPC –0.69% (P = 0.023). By 2020, Black and White AAMR were similar (~4.0–4.2).

- Hispanic (any race): ~5 (1999) to ~2.5 (2015–2016), plateau ~2.2–2.4 (2018), then 4.01 (2020). Joinpoint: –2.16%/year (1999–2018; P < 0.001) then +17.91%/year (2018–2020; P < 0.001). Net AAPC –0.41% (P = 0.09); 2020 approximated White rates.

- Asian/Pacific Islander: Lowest mortality; 44 (1999) to ~1.2 (2017–2018) → 1.87 (2020). No joinpoint; continuous decline –2.36%/year (1999–2020; P < 0.001). The 2020 rise was modest relative to other groups.

Figure 3: Race and ethnicity-stratified trends in age-adjusted rheumatoid arthritis mortality rates, United States, 1999–2020 (Lines representing non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Native American (AI/AN), and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander populations. The AI/AN line is highest and relatively flat, ending around 9 in 2020; White, Black, and Hispanic lines start around 4–6 and decline toward ~2–3, then spike up near 4 in 2020; the Asian line starts ~2.5 and steadily declines below 2).

Figure 3: Race and ethnicity-stratified trends in age-adjusted rheumatoid arthritis mortality rates, United States, 1999–2020 (Lines representing non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, Hispanic, non-Hispanic Native American (AI/AN), and non-Hispanic Asian/Pacific Islander populations. The AI/AN line is highest and relatively flat, ending around 9 in 2020; White, Black, and Hispanic lines start around 4–6 and decline toward ~2–3, then spike up near 4 in 2020; the Asian line starts ~2.5 and steadily declines below 2).

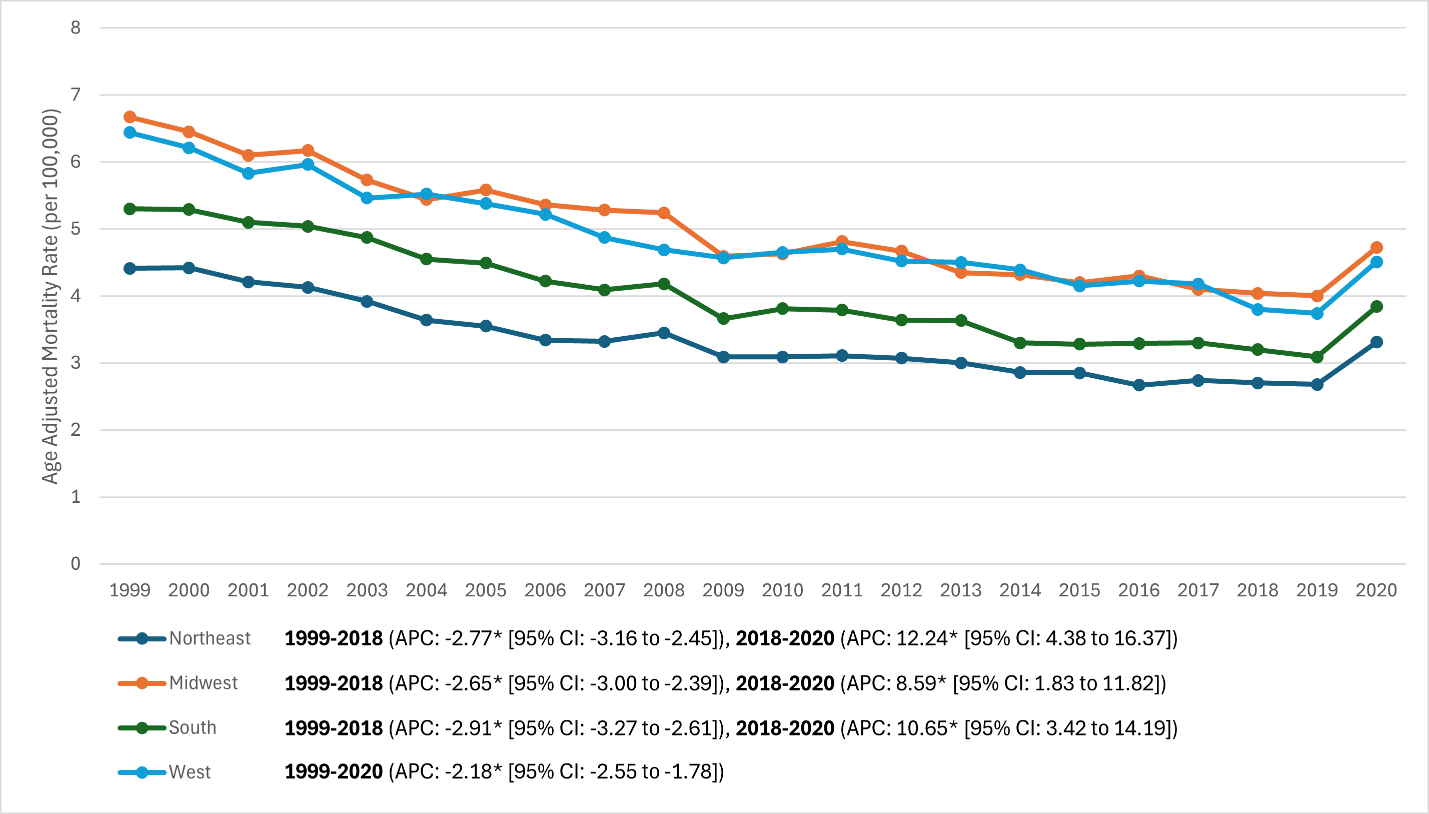

Regional patterns (Fig. 4): All regions declined through ~2018 and increased in 2020, with persistent absolute differences:

- 1999: Highest in Midwest (6.67) and West (6.44); lowest in Northeast (4.41); South

- 2018: Midwest 04, West 3.80, South 3.20, Northeast 2.70 (Northeast remained lowest).

- 2020: Northeast 31, Midwest 4.72 (highest), South 3.84, West 4.51.

Joinpoint APCs (1999–2018): Northeast –2.77%/year, Midwest –2.65%/year, South –2.91%/year (all P < 0.01); West –2.18%/year with no joinpoint detected. Post-2018 APCs: Northeast +12.24%/year (P = 0.003), Midwest +8.59%/year (P = 0.011), South +10.65%/year (P = 0.004); West increased in 2020 without a detected joinpoint. Net 1999–2020 AAPCs across regions were still negative (≈ –1.4% to –1.7%/year; P < 0.001). By 2020, the regional gap narrowed somewhat, but the Midwest/West remained higher than Northeast.

Figure 4: U.S. Census Region-stratified trends in age-adjusted rheumatoid arthritis mortality rates, 1999–2020 (Lines for Northeast, Midwest, South, and West regions. All regions decline from ~4–6 range in 1999 to ~2.5–4 by late 2010s. Northeast remains lowest throughout (~2.7 in 2018) and Midwest highest (~4.0 in 2018). In 2020, all lines tick upward, especially Midwest and South).

Figure 4: U.S. Census Region-stratified trends in age-adjusted rheumatoid arthritis mortality rates, 1999–2020 (Lines for Northeast, Midwest, South, and West regions. All regions decline from ~4–6 range in 1999 to ~2.5–4 by late 2010s. Northeast remains lowest throughout (~2.7 in 2018) and Midwest highest (~4.0 in 2018). In 2020, all lines tick upward, especially Midwest and South).

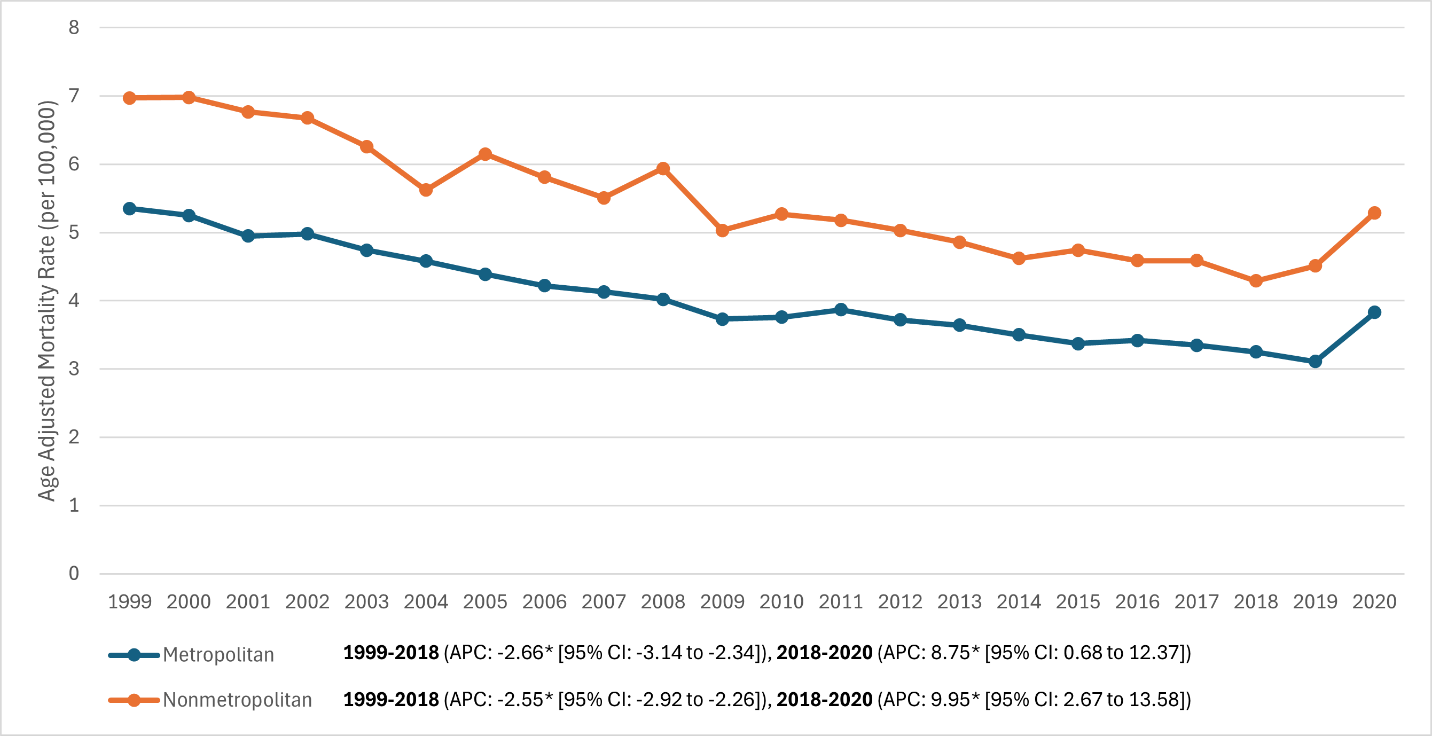

Urban–rural differences (Fig. 5). Non-metropolitan counties had consistently higher RA mortality than metropolitan counties, with similar relative declines pre-2018 and similar increases in 2020:

- 1999: Nonmetro 97 versus metro 5.35 (≈30% higher rural)

- 2018: Nonmetro 29 versus metro 3.25 (gap ≈32%)

- 2020: Nonmetro 29 versus metro 3.83 (gap ≈38%).

Joinpoint APCs: Metro –2.66%/year (1999–2018; P = 0.002) then +8.75%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.033); Nonmetro –2.55%/year (1999–2018; P < 0.001) then +9.95%/year (2018–2020; P = 0.006). CIs overlapped between urban and rural APCs, indicating parallel long-term improvements and pandemic-era setbacks; the absolute burden remained higher in rural areas.

Figure 5: Metropolitan versus non-metropolitan (rural) stratified trends in age-adjusted rheumatoid arthritis mortality rates, 1999–2020 (Two lines showing metro vs. nonmetro. The nonmetro line is consistently above the metro line at all time points. Both decline in parallel [nonmetro from ~7 to ~4, metro ~5.3 to ~3.1 by 2019] and both rise in 2020 [nonmetro to ~5.3, metro to ~3.8], maintaining a gap).

Figure 5: Metropolitan versus non-metropolitan (rural) stratified trends in age-adjusted rheumatoid arthritis mortality rates, 1999–2020 (Two lines showing metro vs. nonmetro. The nonmetro line is consistently above the metro line at all time points. Both decline in parallel [nonmetro from ~7 to ~4, metro ~5.3 to ~3.1 by 2019] and both rise in 2020 [nonmetro to ~5.3, metro to ~3.8], maintaining a gap).

Summary: RA mortality declined broadly from 1999 to the late 2010s across sexes, ages, regions, and urbanicity strata, with the largest absolute burden in older adults and higher absolute rates in women. Disparities persisted: AI/AN populations had the highest and essentially non-improving mortality; rural and Midwest/West residents carried higher rates than urban and Northeast counterparts. A notable rise in 2019–2020 was seen across many strata, most pronounced (in percentage terms) in Black and Hispanic populations, effectively eroding earlier gains. Collectively, the data indicate sustained long-term improvement in RA mortality likely linked to therapeutic advances and comorbidity management, offset by persistent inequities and a pandemic-era reversal detectable in 2020. Figures 1–5 depict overall, sex, age, race/ethnicity, regional, and urban–rural trends accordingly.

U.S. RA mortality declined markedly from 1999 through the late 2010s, consistent with longer-term evidence that modern RA care has narrowed, but not eliminated, the historical survival gap associated with the disease [2,5]. This improvement plausibly reflects earlier diagnosis, treat-to-target strategies, and broader access to effective DMARDs/biologics that reduce systemic inflammation and downstream complications [4]. Parallel advances in CV risk recognition and prevention in RA likely contributed, given the established excess CV mortality in this population [3]. The sharp uptick in 2020 aligns temporally with the COVID-19 pandemic and indicates a recent interruption of these favorable trends.

The overall pattern we observed is concordant with international and population-based reports showing declining RA mortality in the biologic era and incident RA cohorts diagnosed after 2000 no longer exhibiting the same early excess mortality seen in earlier decades [2,5]. That trajectory is biologically and clinically credible: sustained inflammatory suppression lowers atherothrombotic risk, infection risk from uncontrolled disease, and end-organ damage that historically drove deaths [3,4]. In our data, the largest absolute reductions occurred among older adults, those with the highest baseline risk, consistent with treatment and preventive care benefits accruing in the age group that contributes most RA deaths.

Persistent inequities temper this progress. AI/AN populations bore the highest RA mortality, showed little long-term improvement, and experienced disproportionate premature deaths, consistent with independent evidence of worse RA outcomes among North American Indigenous peoples and structural barriers to specialty care [6]. These gaps likely arise from delayed diagnosis, limited rheumatology access, differences in comorbidity burden, and social determinants. Geography and urbanicity further stratify risk: nonmetropolitan residents consistently had higher RA mortality than metropolitan residents, mirroring known utilization and access differences in U.S. rheumatology, although both groups shared similar relative declines before 2018 and parallel increases in 2020 [7].

Racial/ethnic dynamics shifted during the pandemic. Black and Hispanic populations, which had approached or sometimes undercut White RA mortality by the late 2010s, exhibited pronounced pandemic-era increases that erased earlier gains. This is directionally consistent with broader COVID-19 inequities and meta-analytic data showing higher odds of severe infection and mortality among patients with immune-mediated diseases, including RA, especially in older adults and those on glucocorticoids [8]. Under-ascertainment is possible if COVID-19 displaced RA as the underlying cause on death certificates; nonetheless, the spike in RA-coded deaths implies additional pathways (care disruptions, delayed infusions, medication interruptions, deconditioning) that likely worsened outcomes in 2020.

Sex differences persisted: women carried roughly double the absolute RA mortality of men, tracking higher disease prevalence in women, despite substantial pre-pandemic declines in both sexes [1,2]. Whether men have a worse relative prognosis at the individual level is cohort-dependent, but population-level burden remains greater among women, reinforcing the need for sex-aware CV prevention and infection control strategies in RA [3,4].

Pulmonary involvement remains the major outlier. RA-associated interstitial lung disease (RA-ILD) contributes a stubborn, disproportionately lethal share of deaths. Contemporary U.S. vital-statistics analyses show overall RA mortality decreasing while RA-ILD mortality remains largely stable (or declines only modestly in select older strata), indicating that system-wide improvements in RA control have not translated to comparable gains for ILD [9,10]. Given the poor prognosis of fibrotic ILD, delayed detection, limited evidence-based disease-modifying options, and competing risks, targeted strategies, systematic ILD screening in high-risk RA, standardized pathways, and integration of antifibrotic/advanced therapies when indicated, are warranted [9,10]. Alignment with up-to-date treatment guidance (EULAR 2023; ACR 2021) can help sustain disease control and minimize glucocorticoid exposure, which carries infection and metabolic risks relevant to mortality [11,12].

Strengths include a national frame, two decades of observation, and formal trend testing. Limitations are intrinsic to death-certificate data and ecological design. First, underlying-cause coding may under- or misclassify RA; RA often facilitates fatal events (e.g., CV disease, infections) without being recorded as the primary cause, so our estimates likely understate the full mortality burden attributable to RA. Second, we lack a denominator of persons living with RA; AAMR per the general population conflates changes in RA prevalence with changes in case fatality. Epidemiology suggests that incident rates vary over time and survival has improved; still, without patient-level data, we cannot partition rate changes into incidence versus mortality risk [1,2,5]. Third, subgroup differences may reflect unmeasured confounding (socioeconomics, comorbidities, and treatment access) despite age adjustment. Fourth, the short 2018–2020 segment inflates APC estimates; whether the 2020 spike represents a transient shock or a sustained regimen shift requires post-2020 data. Finally, we lack treatment, disease activity, and serologic phenotype; mechanisms behind disparities, particularly in AI/AN communities, cannot be resolved without linked clinical datasets [6].

Clinical and public health implications are direct. Maintain treat-to-target strategies, minimize chronic glucocorticoids, and intensify CV prevention (lipids, blood pressure, smoking cessation) to preserve the hard-won mortality gains [3,4,11,12]. Close equity gaps through improved specialty access on tribal lands and in rural areas, supported by tele-rheumatology, outreach clinics, and streamlined referral pathways [6,7]. Prioritize early identification and coordinated management of RA-ILD through multidisciplinary care and pragmatic screening in high-risk RA phenotypes [9,10]. Pandemic preparedness for immunosuppressed patients, continuity of care, rapid telehealth pivots, proactive vaccination, and clear guidance on medication adjustments should be institutionalized to blunt future shocks [8,11,12].

In sum, two decades of declining RA mortality underscore the impact of modern therapeutics and comorbidity management, yet structural disparities and pulmonary complications compounded by the pandemic limit progress. Ongoing surveillance and targeted implementation anchored in contemporary guidelines are required to restore the downward trajectory and ensure benefits reach all patient groups [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12].

Limitations

This nationwide, death certificate-based analysis carries several limitations. First, cause-of-death coding is imperfect: RA may be under-recorded when proximate causes (e.g., pneumonia, heart failure) are listed without acknowledging RA, or over-recorded when RA is assigned as the underlying cause despite an immediate infectious or CV event. Restricting to underlying-cause deaths enhances specificity but likely underestimates the total RA-attributable burden that would include RA as a contributing cause; coding practices also vary by region and across time. Second, we lacked an annual denominator of persons living with RA; age-adjusted mortality per 100,000 population conflates changes in RA prevalence/incidence with changes in per-patient fatality risk, so declines cannot be attributed solely to improved survival. Third, residual confounding persists despite age stratification: broad racial/ethnic categories mask heterogeneity; socioeconomic status, comorbidities, and access to care were unavailable; metropolitan versus non-metropolitan status is a coarse proxy; and census regions aggregate diverse states. Fourth, trend estimates for 2018–2020 rely on a short terminal window; large positive APCs likely reflect a pandemic-era shock rather than a durable regime shift. Fifth, we lacked clinical granularity – serostatus, disease activity, medication exposures, and key phenotypes such as RA-ILD – precluding mechanism testing and phenotype-specific inference; juvenile RA contributed minimally and was not analyzed separately. Finally, unmeasured secular forces (opioid epidemic, evolving cardiometabolic care, environmental exposures, and healthcare disruptions during COVID-19) may influence mortality trajectories but could not be modeled. These constraints favor conservative interpretation and motivate linked, patient-level studies and multiple-cause-of-death analyses to validate and extend our findings.

From 1999 to 2019, RA age-adjusted mortality declined substantially in the United States, consistent with earlier diagnosis, treat-to-target strategies, and better comorbidity management. A 2020 reversal – coincident with the COVID-19 pandemic – suggests a temporary setback but requires post-2020 surveillance to determine persistence. Disparities remained: higher absolute mortality in women and older adults, markedly elevated and stagnant mortality in AI/AN populations, and persistently higher rates in rural vs urban areas. Closing these gaps will require targeted specialty access, attention to social determinants, and equitable deployment of advanced therapies, alongside continuity-of-care safeguards during public health emergencies.

Treat RA to remission/low activity and intensify cardiovascular prevention to sustain mortality gains. Prioritize high-risk groups – American Indian/Alaska Native, rural, and elderly patients – for outreach, specialty access (including tele-rheumatology), and vaccination/readiness plans. Ensure uninterrupted chronic care during crises to prevent reversals in RA outcomes.

References

- 1. Helmick CG, Felson DT, Lawrence RC, Gabriel S, Hirsch R, Kwoh CK, et al. Estimates of the prevalence of arthritis and other rheumatic conditions in the United States. Part I. Arthritis Rheum 2008;58:15-25. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Dadoun S, Zeboulon-Ktorza N, Combescure C, Elhai M, Rozenberg S, Gossec L, et al. Mortality in rheumatoid arthritis over the last fifty years: Systematic review and meta-analysis. Joint Bone Spine 2013;80:29-33. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Aviña-Zubieta JA, Choi HK, Sadatsafavi M, Etminan M, Esdaile JM, Lacaille D. Risk of cardiovascular mortality in patients with rheumatoid arthritis: A meta-analysis of observational studies. Arthritis Rheum 2008;59:1690-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Smolen JS, Aletaha D, Bijlsma JW, Breedveld FC, Boumpas D, Burmester G, et al. Treating rheumatoid arthritis to target: Recommendations of an international task force. Ann Rheum Dis 2010;69:631-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Widdifield J, Bernatsky S, Paterson JM, Tomlinson G, Tu K, Kuriya B, et al. Trends in excess mortality among patients with rheumatoid arthritis in Ontario, Canada. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:1047-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Hitchon CA, ONeil L, Peschken CA, Robinson DB, Fowler-Woods A, El-Gabalawy H. Disparities in rheumatoid arthritis outcomes for North American Indigenous populations. Int J Circumpolar Health 2023;82:2166447. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Desilet LW, Gavigan K, Bolster MB, Michaud K. Urban and rural patterns of health care utilization among people with rheumatoid arthritis and osteoarthritis in a large US patient registry. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2023;75:1764-74. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Akiyama S, Hamdeh S, Micic D, Sakuraba A. Prevalence and clinical outcomes of COVID-19 in patients with autoimmune diseases: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Rheum Dis 2021;80:384-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Jeganathan N, Nguyen E, Sathananthan M. Rheumatoid arthritis and associated interstitial lung disease: Mortality rates and trends. Ann Am Thorac Soc 2021;18:1970-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Olson AL, Swigris JJ, Sprunger DB, Fischer A, Fernandez-Perez ER, Solomon J, et al. Rheumatoid arthritis-interstitial lung disease-associated mortality. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 2011;183:372-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Smolen JS, Landewé RB, Bergstra SA, Kerschbaumer A, Sepriano A, Aletaha D, et al. EULAR recommendations for the management of rheumatoid arthritis with synthetic and biological disease-modifying antirheumatic drugs: 2022 update. Ann Rheum Dis 2023;82:3-18. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Fraenkel L, Bathon JM, England BR, St Clair EW, Arayssi T, Carandang K, et al. 2021 American College of Rheumatology guideline for the treatment of rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2021;73:924-39. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]