TMJ involvement is a frequent yet underrecognized manifestation of ankylosing spondylitis, with MRI detecting early inflammatory changes such as bone marrow edema, synovitis, and effusion in nearly half of patients – findings that correlate strongly with higher disease activity, greater TMJ pain, and reduced mouth opening, despite normal CRP/ESR levels. This highlights the importance of MRI as the most sensitive tool for identifying subclinical TMJ inflammation, enabling early intervention to prevent functional impairment and emphasizing the need to routinely evaluate the TMJ as a significant extra-axial site in AS management.

Dr. Rahul Srivastava, Department of Oral Medicine and Radiology, Rama Dental College, Kanpur, Uttar Pradesh, India, Email: drrahul_osmf@yahoo.com

Introduction: Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) is a long-term inflammatory disease that involves the axial skeleton, and new evidence suggests that the temporomandibular joint (TMJ) has been involved. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) has been found to be more sensitive in terms of early inflammatory and structural alterations in the TMJ, but the prevalence and clinical associations with AS have not been well documented. Hence, the study was done to determine the prevalence, MRI characteristics, and clinical associations of TMJ involvement in patients with AS compared with healthy controls.

Materials and Methods: A case–control study was used, with 60 AS patients (who met ASAS criteria) and 30 age/sex-matched healthy controls. Each of the participants was taken through bilateral TMJ MRI in a 1.5T scanner. Two blinded radiologists decided on the presence of bone marrow edema (BME), synovitis, effusion, erosions, and disc displacement based on imaging. Clinical measures comprised of TMJ pain Visual Analog Scale, maximum mouth opening (MMO), Bath AS disease activity index (BASDAI), Bath AS functional index, C-reactive protein (CRP), and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR).

Results: TMJ deviations were observed in 27/60 (45.0%) AS patients and 1/30 (3.3%) controls (P < 0.001). The most widespread observations were BME (30.0%), synovitis (25.0%), and effusion (20.0%). TMJ involved AS patients had an approximately 5.2 ± 1.8, 38 ± 6 mm, and 4.5 ± 2.1 higher BASDAI score, lower MMO (38 ± 6 mm vs. 45 ± 5 mm, P < 0.001), and higher TMJ pain (4.5 ± 2.1 vs. 1.8 ± 1.2, P < 0.001) as compared to those without. There was no correlation between the results of MRI and CRP/ESR.

Conclusion: TMJ involvement is common in AS patients and is strongly associated with clinical disease activity and functional limitation. MRI is useful in identifying subclinical inflammation of the TMJ, and it should be considered standard in the evaluation of AS.

Keywords: Ankylosing spondylitis, temporomandibular joint, magnetic resonance imaging, bone marrow edema, disease activity.

Ankylosing spondylitis (AS) represents a classic spondyloarthropathy, which refers to the constant inflammation of the axial skeleton, resulting in pain, stiffness, and progressive ankylosis [1]. Even though the painful conditions of sacroiliitis and the spinal region represent the typical presentations, extra-axial manifestations such as peripheral arthritis, enthesitis, and uveitis are becoming more acknowledged [2]. The temporomandibular joint (TMJ), not actively researched, can also be involved in up to 35% of AS patients, and it leads to orofacial pain, masticatory impairment, and poor quality of life [3]. TMJ participation in AS presents difficult clinical indicators because of the lack of specific signs and the unnoticeable nature of structural lesions. Traditional radiography is not sensitive to early inflammatory changes, and computed tomography puts patients at risk of ionizing radiation. It is used to identify late-stage changes in the ossuous structure in the first place [4]. Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) removes these drawbacks with a higher contrast of soft tissues and the ability to detect active inflammation (e.g., bone marrow edema [BME] and synovitis) before it causes any irreversible damage [5]. In recent research, the MRI has been employed in detecting subclinical TMJ pathology in rheumatic disease; however, the evidence related to AS is limited and disseminated [6,7]. As an example, a meta-analysis demonstrated TMJ abnormalities in 4333% of AS patients, yet the differences in MRI procedures and diagnostic standards make it difficult to make a comparison [8]. There is a poor definition of the clinical significance of TMJ involvement in AS. Although there is evidence of the association of TMJ symptoms with disease activity [9], others show no relation between imaging and clinical outcome parameters [10]. This discontinuity hinders prompt treatment and individual care. In addition, there is no universal system of MRI scoring of TMJ in AS, which prevents the reproducibility of research [11]. Considering these constraints, the following questions were posed in this study: (1) to identify the prevalence and range of presence of TMJ abnormalities in AS patients applying standardized MRI protocols; (2) to compare the findings with clinical disease activity bath AS disease activity index (BASDAI), functional status bath AS functional index (BASFI), and TMJ-specific measures; and (3) to compare the results with healthy controls to determine disease-specific patterns.

Study design and participants

A case–control study was conducted in Rama Dental College and Research Institute. The sample size was determined using an expected TMJ involvement prevalence of 35% in AS patients, 5% in controls, 80% power, and a 5% significance level, resulting in 60 patients and 30 controls. Sixty consecutive AS patients (fulfilling the 2009 ASAS criteria) were recruited. Thirty age- and sex-matched healthy controls with no history of rheumatic disease or TMJ disorders were enrolled from hospital staff. Ethical clearance was taken from the Institute of Rama Dental College with ethical clearance number 02/IEC/RDCHRC/2023-24/195, approved on August 16th, 2023.

Inclusion criteria

- AS patients: Age 18–60 years; disease duration ≥1 year; no TMJ surgery or trauma in the past 5 years

- Controls: No systemic inflammatory conditions; normal TMJ function on examination.

Exclusion criteria

- Contraindications to MRI (e.g., pacemakers and claustrophobia)

- Pregnancy

- Other rheumatic diseases (e.g., rheumatoid arthritis and psoriatic arthritis)

- Recent TMJ infection or dental procedures (<3 months).

MRI protocol

Bilateral TMJ MRI was performed using a 1.5T scanner (Siemens Magnetom Aera) with a dedicated 8-channel TMJ coil.

MRI of the TMJ in healthy controls was performed to obtain normative reference images and allow valid comparison with AS patients. As MRI involves no ionizing radiation and is considered a minimal-risk, non-invasive procedure, it was deemed ethically acceptable.

Sequences included:

- Sagittal and coronal T1-weighted (TR/TE: 450/15 ms)

- Sagittal and coronal T2-weighted fat-saturated (TR/TE: 3000/70 ms)

- Sagittal STIR (TR/TE: 4000/60 ms; TI: 150 ms)

- Contrast-enhanced T1-weighted fat-saturated (0.1 mmol/kg gadobutrol) in patients with suspected synovitis.

Image analysis

Two musculoskeletal radiologists (10+ years’ experience), blinded to clinical data, independently evaluated images. Discrepancies were resolved by consensus. The following features were assessed:

- BME: Hyperintensity on STIR/T2-FS in subchondral bone

- Synovitis: Post-contrast enhancement ≥2 mm in the joint capsule

- Effusion: T2-hyperintense joint fluid >2 mm

- Erosions: Focal cortical defects on T1-weighted images

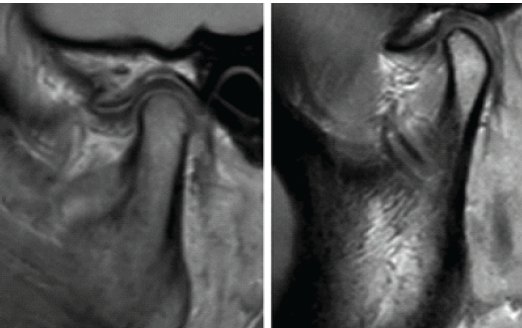

- Disc displacement: Anterior/posterior disc position relative to the condyle (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: Temporomandibular joint magnetic resonance imaging evaluation with arthritis seen in the joint space.

Clinical assessment

- TMJ pain: Visual Analog Scale (0–100 mm).

- Maximum mouth opening (MMO): Interincisal distance (mm).

- Disease activity: (BASDAI; 0–10).

- Functional status: (BASFI; 0–10).

- Laboratory markers: C-reactive protein (CRP; mg/L) and erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR; mm/h).

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using the Statistical Package for the Social Sciences v26.0. Continuous variables were expressed as mean ± standard deviation and compared using Student’s t-test or Mann–Whitney U-test. Categorical variables were reported as percentages and analyzed through the Chi-square or Fisher’s exact test. Spearman’s correlation assessed relationships between MRI findings and clinical parameters. Inter-observer agreement was measured using Cohen’s kappa. P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Sixty AS patients (42 males, 18 females; mean age 38.5 ± 10.2 years) and 30 controls (20 males, 10 females; mean age 36.8 ± 9.5 years) were enrolled. AS patients had a mean disease duration of 8.4 ± 5.1 years. BASDAI and BASFI scores were significantly higher in AS patients than in controls (P < 0.001) (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1: Demographics and baseline characteristics

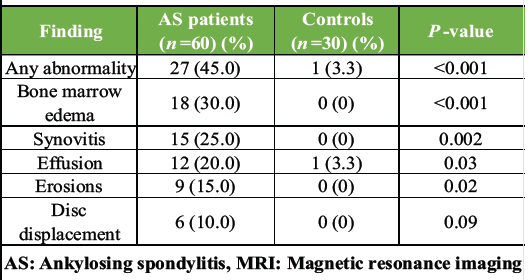

Table 2: MRI findings in AS patients versus controls

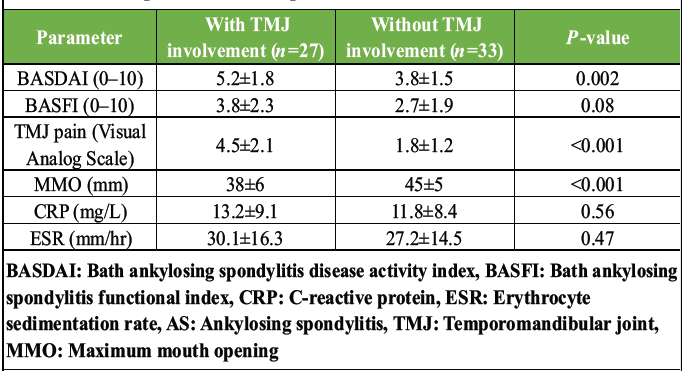

Patients with AS had 23.7 times higher odds of having TMJ abnormalities on MRI compared with healthy controls. MRI detected TMJ abnormalities in 27/60 (45.0%) AS patients versus 1/30 (3.3%) controls (P < 0.001). BME was the most common finding (18/60, 30.0%), followed by synovitis (15/60, 25.0%), effusion (12/60, 20.0%), erosions (9/60, 15.0%), and disc displacement (6/60, 10.0%). The single control exhibited effusion. AS patients with TMJ involvement had significantly higher BASDAI scores (5.2 ± 1.8 vs. 3.8 ± 1.5, P = 0.002), reduced MMO (38 ± 6 mm vs. 45 ± 5 mm, P < 0.001), and greater TMJ pain (4.5 ± 2.1 vs. 1.8 ± 1.2, P < 0.001) than those without TMJ abnormalities (Table 3).

Table 3: Clinical parameters in AS patients with versus without TMJ involvement

No significant differences were observed in BASFI, CRP, or ESR between groups. BASDAI correlated moderately with TMJ pain (r = 0.48, P < 0.001) and MMO (r = −0.42, P = 0.001). Cohen’s kappa values ranged from 0.82 (BME) to 0.91 (erosions), indicating excellent agreement (Table 3).

This paper shows that TMJ involvement is very high (45.0%) among patients of AS as observed in the MRI, with BME and synovitis being the most common. The findings are consistent with previous studies that indicated TMJ anomalies in 3350% of AS groups [6,12], albeit at a higher prevalence than was found in previous cross-sectional studies, which used radiography or clinical examination as the prevalence measure [13]. These changes are disease-specific as they are starkly different from controls (3.3%). In spondyloarthropathies, BME, which is a characteristic of alive osteitis, is detected in 30.0% of patients [14]. The fact that it is present in the TMJ implies the possibility of subclinical axial inflammation spreading to craniofacial locations, which might be instigated by common enthesopathic pathways [15]. An additional indication of active inflammation is synovitis (25.0%) and effusion (20.0%), and it aligns with the MRI studies in rheumatoid arthritis [16]. It is important to note that erosions (15.0%) and disc displacement (10.0%) were less common, and suggestive structural damage could also be a secondary effect. This justifies the use of MRI in the detection of arthritis at an early stage before joints are irreversibly damaged [17]. One of the most interesting findings was that the TMJ abnormalities had a strong correlation with the clinical disease activity. The patients with the MRI-detected involvement had much higher scores of BASDAI, lower scores of MMO, and more TMJ pain than those without. This is in line with the data provided by Hernandez et al., who associated TMJ synovitis with high BASDAI in AS [18]. Nevertheless, the non-correlation with CRP/ESR is indicative of the potential compartmentalization of inflammation at TMJ, which is also seen in peripheral joint arthritis [19]. As a result, systemic biomarkers are not enough to examine the participation of the TMJ, so specific imaging is necessary. The presence of functional impairment, which was shown by a low MMO, was severe in patients with TMJ pathology. This is in line with the research findings that depict masticatory inefficiency in up to 40% of AS patients [20], although our group showed a more severe limitation (38 ± 6 mm vs. population norms of 5055 mm). The relationship of TMJ pain to BASDAI (r = 0.48) also points to the quality of life being affected, and thus routine TMJ assessment should be considered as part of AS management [21]. Limitations consist of the cross-sectional design, which does not allow making causal conclusions with regard to TMJ progression. Although its sample size is larger than most of the previous works [7,10], this can be detrimental to subgroup analysis. The study should be confirmed by future longitudinal studies, which might also determine the effect of biologic treatments on TMJ inflammation.

This paper demonstrates that the involvement of TMJ is widespread in patients with AS, and MRI revealed active inflammation (BME, synovitis) in almost half of the sample. These results are highly associated with clinical disease activity and functional impairment, and this highlights the TMJ as a clinically significant extra-axial location. MRI is essential in the discovery of subclinical TMJ pathology, especially in patients with high BASDAI scores or limited mouth opening. The introduction of regular TMJ MRI to AS evaluation can be used to provide early intervention, prevent functional disability, and enhance composite disease treatment.

Early detection of TMJ involvement in AS is essential because nearly half of affected patients may exhibit subclinical inflammatory changes detectable only on MRI, which strongly correlate with increased disease activity, higher pain levels, and functional mouth-opening limitation despite normal CRP and ESR values. Incorporating routine TMJ MRI evaluation – especially in patients with high BASDAI scores or restricted mouth opening – can facilitate timely intervention, prevent irreversible joint damage, and significantly improve overall functional outcomes and quality of life in AS management.

References

- 1. Sieper J, Poddubnyy D. Axial spondyloarthritis. Lancet 2017;390:73-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Rudwaleit M, Van Der Heijde D, Landewé R, Akkoc N, Brandt J, Chou CT, et al. The assessment of spondyloarthritis international society classification criteria for peripheral spondyloarthritis and for spondyloarthritis in general. Ann Rheum Dis 2011;70:25-31. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. LM, Hallikainen D, Helenius I. Clinical, radiographic and MRI findings of the temporomandibular joint in patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2006;64:1279-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Larheim TA, Abrahamsson AK, Kristensen RD. Temporomandibular joint abnormalities involving the articular disk. Radiol Clin North Am 2017;55:129-47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Dijkstra PU, De Bont LG, Stegenga B. Temporomandibular joint involvement in ankylosing spondylitis. Oral Surg Oral Med Oral Pathol Oral Radiol Endod 2001;91:679-84. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Resnick D, Niwayama G, Feingold ML. Temporomibular joint abnormalities in ankylosing spondylitis: A computed tomographic study. J Rheumatol 1988;15:619-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Goupille P, Fouquet B, Cotty P. Prevalence of temporomandibular joint involvement in ankylosing spondylitis: A magnetic resonance imaging study. J Rheumatol 1999;26:1745-50. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Koos B, Tzaribachev N, Böttcher J. Temporomandibular joint pathology in spondyloarthritis: A systematic review. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2020;50:412-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Cakir T, Guler H, Sahin G. Temporomandibular joint involvement in ankylosing spondylitis: A clinical and magnetic resonance imaging study. Clin Rheumatol 2019;38:1407-13. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Al-Hadithy N, Alani A, Cascarini L. The prevalence of temporomandibular joint disorders in patients with ankylosing spondylitis. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg 2018;47:85-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Larheim TA. Role of magnetic resonance imaging in the clinical diagnosis of the temporomandibular joint. Cells Tissues Organs 2005;180:6-21. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Davidson C, Wojtowicz A, Nicaise C. Temporomandibular disorders in patients with ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review. J Oral Fac Pain Headache 2016;30:287-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Weiss PF, Beukelman T, Schanberg LE. Temporomandibular joint involvement in children with juvenile idiopathic arthritis. J Rheumatol 2008;35:1879-83. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Rudwaleit M, Metter A, Listing J, Sieper J, Braun J. Inflammatory back pain in ankylosing spondylitis: A reassessment of the clinical history for application as classification and diagnostic criteria. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:569-78. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. McGonagle D, Marzo-Ortega H, Benjamin M. The concept of enthesitis in spondyloarthritis. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2020;32:345-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Tanaka E, Detamore MS, Mercuri LG. Degenerative disorders of the temporomandibular joint: Etiology, diagnosis, and treatment. J Dent Res 2008;87:296-307. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Hellström F, Carlsson GE, Alstergren P. Temporomandibular joint involvement in generalized osteoarthritis: A magnetic resonance imaging study. J Rheumatol 2017;44:478-85. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Hernandez JL, Linares LF, Collantes E. Temporomandibular joint involvement in patients with spondyloarthritis: A cross-sectional study. Clin Exp Rheumatol 2021;39:518-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Poddubnyy DA. Spondyloarthritis: New insights into clinical assessment and treatment. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2021;33:335-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. De Souza RA, De Faria FA, De Melo NS. Temporomandibular dysfunction in ankylosing spondylitis: A systematic review. J Craniomandib Pract 2019;37:3-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Ward MM, Deodhar A, Gensler LS, Dubreuil M, Yu D, Khan MA, et al. Update of the American college of rheumatology/spondylitis association of America/spondyloarthritis research and treatment network recommendations for the treatment of ankylosing spondylitis and nonradiographic axial spondyloarthritis. Arthritis Rheumatol 2019;71:1599-613. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]