Spinal osteochondromas from the pedicle are extremely rare presentation that can cause compressive myelopathy and it requires surgical excision.

Dr. Mantu Jain, 102/J, Cosmopolis, Bhubaneswar - 751019, Odisha, India. Email-montu_jn@yahoo.com

Introduction: Osteochondromas are benign bony neoplasms typically located in long bones, though they may occasionally occur in the posterior elements of the spine.

Case Report: We present a case of a 10-year-old boy with multiple osteochondromas diagnosed with hereditary multiple exostoses, who exhibited symptoms of thoracic myelopathy. Radiological investigations indicated a heterogeneous mass on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) that was encroaching upon the spinal canal. The computed tomography scan verified the presence of a pedunculated exostosis originating from the right D4 pedicle. The mass was excised through a right lateral extracavitary approach and sent for histopathological examination, which confirmed the diagnosis. The patient exhibited improvement and achieved full recovery within 6 months.

Conclusion: Osteochondromas of the spine are infrequently symptomatic. Early diagnosis with clinical features and MRI will help to initiate treatment.

Keywords: Osteochondroma, dorsal spine, pedicle, compressive myelopathy.

Osteochondromas are a benign outgrowth of bone and cartilage and one of the most common bone tumors that usually occur in long bones [1,2,3]. While <5% of solitary osteochondromas arise in the spine, more than 50% of patients with hereditary multiple exostoses (HME) present with spinal osteochondromas [4,5]. These spinal growths tend to affect the posterior elements of the cervical or thoracic regions. Clinical symptoms range from pain, spinal deformity, and radicular or myelopathic symptoms due to neural compression [5,6]. Although the progression of symptomatic spinal exostoses is generally gradual, rapid neurological decline can still occur. The risk of malignant transformation is low, however, patients with HME are at a higher risk. Surgical excision after a detailed radiological analysis has shown good outcomes in long-term follow-up. We present a case of a solitary osteochondroma of the pedicle of the dorsal spine at the D4 level causing compressive myelopathy in a patient diagnosed with HME.

A 10-year-old male patient presented with bilateral lower limb weakness for 15 days. The onset of weakness was sudden, affecting both lower limbs and associated with spasticity and upper motor signs. His sensory was intact, and so was his bladder and bowel control. The patient had a notable medical history of swellings located in both arms and thighs, which had been present since the age of five. These swellings were painless and had gradually increased in size over time. Aside from this condition, he was otherwise healthy, with no known allergies and not currently on any medications. The family history revealed a significant pattern, as multiple relatives on the paternal side had experienced similar issues with painless bony masses at a young age. His father, two paternal uncles, and an aunt all exhibited similar bony growths on their legs and hands. In addition, his paternal grandfather and great uncle had reported comparable symptoms, and a paternal cousin was also affected. Upon physical examination, multiple palpable masses were detected in the right arm and both thighs, characterized by a bony consistency and immobility. The examination also revealed hypertonia and hyperreflexia in both lower limbs, with muscle strength assessed at 2/5 on medical research council grading in the lower extremities. Ultimately, the patient was diagnosed with HME. Plain radiography of the skeletal survey revealed that there are multiple osteochondromas (Fig. 1).

Figure 1: X-rays displaying multiple locations of exostosis.

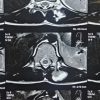

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the whole spine revealed a swelling at the D4 level (heterogenous intensity without fluid levels suggestive of osteochondroma) compressing the spinal cord (Fig. 2a and b). A computed tomography (CT) further detailed a bony pedunculated arising from the right pedicle (suggestive of exostosis) and encroaching the spinal canal (Fig. 2c and d). The patient’s family was counselled for surgical excision. The patient was placed prone, and the right lateral extracavatory approach (LECA) was used to open the canal after excising a part of the 4th rib and tracing the neurovascular bundle to the foramen.

Figure 2: Magnetic resonance images Sagittal (a) and axial cuts (b) showing a hypointense mass encroaching the canal and pressing the spinal cord; computed tomography confirmed the mass to be arising from the right pedicle (c) and encroaching spinal canal (d) steps of lateral extracavatory approach approach shoeing excision of the mass and spinal cord falling back (e and f).

Hemilaminectomy was done, and the cord was seen to stretch over the mass. The pedicle was burred along with part of the mass, and the remaining portion was removed, which displayed a bony swelling with glistening cartilage (Fig. 2e, f, g). The cord was seen to fall back and be pulsatile at the end of the procedure. A postoperative X-ray was taken (Fig. 3a and b), and a CT scan (Fig. 3c) confirmed complete removal of the mass, and the patient was sent for physiotherapy.

Figure 3: Post-operative X-ray (A and B) and computed tomography scan (C) showing complete excision of the mass.

Histopathology showed normal primary trabeculae with a cartilaginous cap, confirming the diagnosis of osteochondroma. Post-surgery, the patient started to improve, and by 6 months, he was independently ambulatory.

HMEs, also known as osteochondromatosis, is an inherited, autosomal dominant disorder associated with a mutation in the tumor suppressor genes exostosin-1 and -2 (EXT1 and EXT2) [7], which are responsible for the synthesis of heparan sulfate proteoglycans (HSPG), resulting in HSPG deficiency and subsequent development of multiple osteochondromas, which are seen throughout the skeleton. Spinal osteochondromas, though rare, are clinically significant due to the morbidity they cause in terms of neurological complications. The disease more commonly affects males. The cervical spine is the most frequent site of spinal osteochondromas, constituting around 49% of all cases, hypothesized to be due to higher mobility in this region [4]. The rate of ossification in the secondary centers of the spine has been hypothesized to determine the distribution of the lesions.[8]. Thoracic and lumbar osteochondromas are even rarer [8,9,10]. Diagnosis is difficult due to diverse clinical presentations, the gradual progression of symptoms, and poor demonstration on imaging. Radiographs of the spine or an anteroposterior projection of the chest show projections from vertebrae, but CT is the preferred modality, demonstrating the contiguous cortex of the host bone and tumor, along with the amount of occlusion of the canal space with potential intrusion into the foramen [11]. Cartilaginous cap thickness provides a guide to rule out malignant change. Caps in adults do not exceed more than 1 cm and are difficult to identify on CT scans. Malignancy is suspected if the size is more than 3 cm thick [12,13]. MRI scans are important to visualize the extent of spinal compression and the adjacent soft tissue environment to plan the dissection and excisions. A full screening of the spine may reveal other incidental osteochondromas. The patient noticed his symptoms from the past 2 weeks. Considering his diagnosis of HME from a young age, along with the absence of constitutional symptoms or weight loss, it is possible that the growth of the tumor was gradual and the finding was seen on demonstration of the symptoms. The transformation of solitary osteochondromas into chondrosarcoma is uncommon, occurring in about 1% of cases. However, individuals with HME face a higher risk, with malignant transformation reported in more than 5–10% of cases [1,14,15]. Other causes of acute-onset non-traumatic causes of paraparesis in the young may include a spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma [16]. These are seen in patients with congenital or acquired bleeding disorders and arteriovenous malformations. They may also occur rarely in pregnancy [17]. Similarly, while vertebral hemangiomas are mostly dormant and found incidentally [18], an aggressive variant of hemangioma produces early neurological symptoms requiring a surgical intervention. Our case is unique because the spinal lesion is solitary, in a less frequent region of affection (dorsal spine), and arising from the pedicle, which is an unusual anatomic location. The mass was therefore encroaching into the spinal canal, leading to compressive myelopathy with rapidly progressive symptoms, which is an atypical clinical presentation. Surgical intervention leads to neurological improvement in over 80% of cases where solitary osteochondroma compromises the spinal cord [19,20]. In osteochondromas, the goal of en bloc resection signifies the excision of the cartilaginous cap. We used the LECA to identify and excise the tumor, leading to decompression of the cord. LECA provides good dorsal and ventrolateral exposure to the thoracic spine with the added advantage of introducing the instrumentation posteriorly through the same incision [21]. Surgeons should be wary of pulmonary complications, which are the major cause of morbidity postoperatively in the form of hemothorax, pleural effusions, or pneumonia, all of which may require thoracostomy tubes and intensive care [22]. A postoperative CT scan confirmed adequate excision of the lesion with regained space for the neural tissue. Since the tumor was in the posterior elements, it was amenable to removing the lamina and spinous process. Long-term follow-up of patients undergoing excision has shown good outcomes in terms of neurological recovery with low morbidity to the patient [23]. Talac et al. found a local recurrence of 11% even with negative margins and en bloc resection. This warrants a need for ongoing clinical and radiological monitoring due to the risk of recurrence or potential sarcomatous transformation, especially in cases with HME [24].

Osteochondromas of the spine are infrequently symptomatic. Early diagnosis with clinical features and MRI will help to initiate treatment. A meticulous surgical planning and a sound rehabilitation protocol, in addition to close follow-up, will drive higher patient satisfaction rates and lower complications.

Osteochondromas of the spine arising from the pedicle and encroaching on the spinal canal are extremely and it requires excision when associated with clinical symptoms.

References

- 1. Tepelenis K, Papathanakos G, Kitsouli A, Troupis T, Barbouti A, Vlachos K, et al. Osteochondromas: An updated review of epidemiology, pathogenesis, clinical presentation, radiological features and treatment options. In Vivo 2021;35:681-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Kitsoulis P, Galani V, Stefanaki K, Paraskevas G, Karatzias G, Agnantis NJ, et al. Osteochondromas: Review of the clinical, radiological and pathological features. In Vivo 2008;22:633-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Alabdullrahman LW, Mabrouk A, Byerly DW. Osteochondroma. In: StatPearls. Treasure Island, FL: StatPearls Publishing; 2024. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK544296 [Last accessed on 2024 Nov 17]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Albrecht S, Crutchfield JS, SeGall GK. On spinal osteochondromas. J Neurosurg 1992;77:247-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Bari MS, Jahangir Alam MM, Chowdhury FR, Dhar PB, Begum A. Hereditary multiple exostoses causing cord compression. J Coll Physicians Surg Pak 2012;22:797-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Gigi R, Kurian BT, Cole A, Fernandes JA. Late presentation of spinal cord compression in hereditary multiple exostosis: Case reports and review of the literature. J Child Orthop 2019;13:463-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Wuyts W, Schmale GA, Chansky HA, Raskind WH. Hereditary multiple osteochondromas. In: Adam MP, Feldman J, Mirzaa GM, Pagon RA, Wallace SE, Amemiya A, editors. GeneReviews®. Seattle, WA: University of Washington, Seattle; 1993. Available from: http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK1235 [Last accessed on 2024 Nov 16]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Fiumara E, Scarabino T, Guglielmi G, Bisceglia M, D’Angelo V. Osteochondroma of the L-5 vertebra: A rare cause of sciatic pain. Case report. J Neurosurg 1999;91 2 Suppl:219-22. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Gader G, Gharbi MA, Kharrat MA, Harbaoui A, Zammel I. Solitary thoracic spine osteochondroma: A rare cause for spinal cord compression. Spinal Cord Ser Cases 2024;10:63. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Zaher MA, Alzohiry MA, Fadle AA, Khalifa AA, Refai O. Fifth lumbar vertebrae solitary osteochondroma arising from the neural arch, a case report. Egypt J Neurosurg 2021;36:30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Palmer FJ, Blum PW. Osteochondroma with spinal cord compression: Report of three cases. J Neurosurg 1980;52:842-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Kenney PJ, Gilula LA, Murphy WA. The use of computed tomography to distinguish osteochondroma and chondrosarcoma. Radiology 1981;139:129-37. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Hudson TM, Springfield DS, Spanier SS, Enneking WF, Hamlin DJ. Benign exostoses and exostotic chondrosarcomas: Evaluation of cartilage thickness by CT. Radiology 1984;152:595-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Bovée JV. Multiple osteochondromas. Orphanet J Rare Dis 2008;3:3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Murphey MD, Choi JJ, Kransdorf MJ, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH. Imaging of osteochondroma: Variants and complications with radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2000;20:1407-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Alexiadou-Rudolf C, Ernestus RI, Nanassis K, Lanfermann H, Klug N. Acute nontraumatic spinal epidural hematomas. An important differential diagnosis in spinal emergencies. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 1998;23:1810-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Naik S, Jain M, Sethi P, Mishra N, Bhoi SK. Spontaneous spinal epidural hematoma in a near-term pregnant patient. J Orthop Case Rep 2022;12:11-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Timilsina K, Shrestha S, Bhatta OP, Paudel S, Lakhey RB, Pokharel RK. Atypical aggressive hemangioma of thoracic vertebrae associated with thoracic myelopathy-a case report and review of the literature. Case Rep Orthop 2024;2024:2307950. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Gille O, Pointillart V, Vital JM. Course of spinal solitary osteochondromas. Spine (Phila Pa 1976) 2005;30:E13-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Zaijun L, Xinhai Y, Zhipeng W, Wending H, Quan H, Zhenhua Z, et al. Outcome and prognosis of myelopathy and radiculopathy from osteochondroma in the mobile spine: A report on 14 patients. J Spinal Disord Tech 2013;26:194-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Foreman PM, Naftel RP, Moore TA 2nd, Hadley MN. The lateral extracavitary approach to the thoracolumbar spine: A case series and systematic review. J Neurosurg Spine 2016;24:570-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Resnick DK, Benzel EC. Lateral extracavitary approach for thoracic and thoracolumbar spine trauma: Operative complications. Neurosurgery 1998;43:796-802; discussion 802-3. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Sciubba DM, Macki M, Bydon M, Germscheid NM, Wolinsky JP, Boriani S, et al. Long-term outcomes in primary spinal osteochondroma: A multicenter study of 27 patients. J Neurosurg Spine 2015;22:582-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Talac R, Yaszemski MJ, Currier BL, Fuchs B, Dekutoski MB, Kim CW, et al. Relationship between surgical margins and local recurrence in sarcomas of the spine. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2002;397:127-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]