GCT requires aggressive treatment to avoid future recurrences, and the use of vascularized metatarsal transfer is a viable reconstruction option after en bloc resection of the involved metatarsal.

Dr. Sunil D Magadum, Department of Orthopaedics, No. 4/112, Miot Hospitals, Mount Poonamallee Rd, Sathya Nagar, Manapakkam, Chennai, Tamil Nadu 600089. E-mail: drsunil1304@gmail.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) (osteoclastoma) is a locally aggressive bone neoplasm with an incidence of 3–8% of all bone tumors, rarely seen (1–2%) in smaller bones of the feet. It is located in the epiphysis-metaphysis of long bones. If inadequately treated, they have a high recurrence rate.

Case Report: It is a rare case report of recurrent GCT of the first metatarsal in a 28-year-old female who was previously treated with curettage and bone grafting. After confirmation of the lesion with fine needle aspiration cytology, she underwent en bloc resection of the first metatarsal with vascularized transfer of the second metatarsal to the first metatarsal.

Results: She was initially started with partial weight-bearing walking with elbow crutches, and full weight-bearing was started at 4 months. She was followed for over 12 years without recurrence. Functional outcomes assessed by the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society scoring system showed significant improvement, with midfoot and hallux metatarsophalangeal-interphalangeal scores increasing from 22 to 91 and 30 to 87, respectively.

Conclusion: GCTs of the small bones of the foot, though rare, exhibit aggressive behavior and high recurrence. En bloc resection with vascularized second metatarsal transfer offers a reliable reconstructive option with excellent long-term functional outcomes and minimal donor site morbidity if it involves the entire metatarsal. This technique is a viable limb-salvage alternative to amputation in recurrent GCT of the first metatarsal.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, curettage, en bloc resection, vascularized metatarsal transfer, recurrent giant cell tumor.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone, also known as osteoclastoma, is a locally aggressive, typically benign neoplasm characterized histologically by a richly vascularized stroma composed of proliferating mononuclear stromal cells interspersed with uniformly distributed, osteoclast-like multinucleated giant cells [1]. GCT accounts for approximately 3–8% of all primary bone tumors [2], with a peak incidence in the third decade of life. Notably, over 90% of cases are diagnosed in individuals older than 20 years, with a slight female predominance [3]. In skeletally immature patients, GCT tends to arise in the metaphysis, whereas in adults, the tumor typically involves the epiphyseal-metaphyseal regions of long bones, particularly the distal femur, proximal tibia, and distal radius [4]. Involvement of small bones of the hands and feet is rare, comprising only 1–2% of all GCT cases [5]. Axial skeletal involvement is uncommon, except in the sacrum, which is a recognized site of predilection [6]. Multicentric GCTs are more frequently observed in younger patients and are often associated with a shorter duration of symptoms [7]. Although GCTs are generally classified as benign, they are notorious for their aggressive local behavior and relatively high recurrence rates, especially following intralesional procedures [8]. Pulmonary and other distant metastases have been reported in approximately 3.5% of cases [9], and recurrent lesions are believed to carry a greater risk of malignant transformation compared to primary tumors [10,11]. The primary goals in managing GCT include complete tumor eradication, preservation of limb function, and prevention of both local recurrence and distant metastasis. Various reconstruction techniques have been described in the literature following wide resection, including the use of fibular grafts, tricortical bone grafts, and other structural autografts. However, there is limited evidence on vascularized metatarsal transfer for reconstruction in the foot following en bloc resection. In this report, we present a rare case of recurrent GCT involving the first metatarsal, managed successfully with en bloc resection and vascularized second metatarsal transfer. We describe the surgical technique, functional recovery, and long-term outcomes over a 12-year follow-up period, highlighting this limb-salvage approach as a viable reconstructive option for recurrent GCT in small bones of the foot.

A 28-year-old active female from South India presented with dull aching pain and swelling over the dorsum of the right great toe for the past 8 months (Fig. 1).

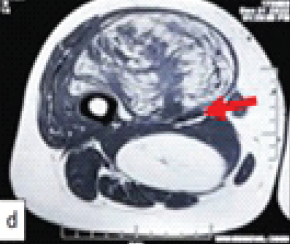

Figure 2: Computed tomography images showing a large expansile lytic lesion involving the entire metatarsal with thinning of cortices and bone grafts within the cavity.

The swelling was insidious in onset, which progressively increased in size. The pain first started as mild in intensity and intermittent in nature, which advanced to dull aching, continuous pain. She has consulted an orthopedic surgeon and underwent open biopsy, curettage, and bone grafting. The biopsy report showed a GCT. Post-procedure, she was asymptomatic for 4 months, then the pain and swelling recurred. Recurred pain was severe in intensity, continuous, and dull aching. On examination, there was a diffuse swelling over the dorsomedial aspect of the first metatarsal, which was firm in consistency and fixed to the underlying bone. The skin over the swelling was free. A previous surgical scar was seen over the dorsomedial aspect of the first metatarsal. Tenderness was present over the metatarsal on deep palpation. The movements of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint were painful and restricted.

X-ray and computed tomography show an expansile osteolytic lesion of the entire 1st metatarsal with the presence of loose pieces (bone graft from previous surgery) of bone lying within the cavity, with thin septa separating the lytic cavities, and with thinning of the cortices (Figs. 2 and 3). Routine blood chemistry was normal. The patient underwent fine needle aspiration cytology, which confirmed the diagnosis of GCT. A CT scan of the chest was done to rule out lung involvement.

Figure 3: Intraoperative images showing the lesion involving the entire metatarsal and following resection and reconstruction.

After thorough clinic-radiological and histological evaluation, she was planned for en bloc resection of the first metatarsal, reconstruction with vascular transfer of the second metatarsal to the first metatarsal, and amputation of the second toe. Magnetic resonance angiography was done to assess the vascular status of the first and second metatarsals.

Surgical technique

An elliptical incision was taken around the previous scar, extended proximally and distally. The previous scar was excised along with the underlying subcutaneous tissues. The extensor hallucis longus tendon was retracted laterally, and en bloc resection of the first metatarsal was done. Wedge was made in medial cuneiform articular surface, vascular transfer of the second metatarsal was done to the first ray (Fig. 4).

Figure 4: Post-operative X-rays showing semitubular plate fixation for the metatarsocuneiform joint and K-wires in the metatarsophalangeal joint and base of the 2nd metatarsal-cuneiform joint.

A five holed 2.7 mm semitubular plate was used to stabilize the metatarso-cuneiform joint and a K-wire for metatarso-phalangeal joint, the base of second metatarsal was fused with intermediate cuneiform to maintain the arch support (Fig. 5).

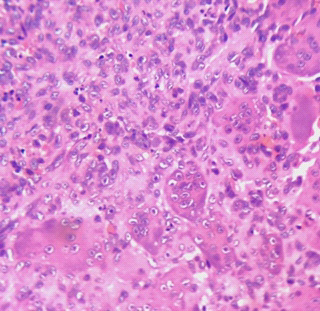

Figure 5: Histopathology-spindle-shaped mononuclear tumor cells amidst which osteoclastic giant cells are seen.

The second toe was amputated. A plaster of Paris slab was applied below the knee. Postoperatively, the distal neurovascular status was assessed and found to be normal. Histopathology study of the resected specimen was consistent with GCT (Fig. 6).

Figure 6: 4-year follow-up X-ray after removal of the plate and clinical picture.

Post-operative care

K-wires were removed after 10 weeks, and she was made to weight bear gradually with the help of two elbow crutches. She started full-weight bearing walking at the end of 4 months. The patient was followed up every 6 months. She underwent removal of the plate after 4 years of the index surgery. Till her last follow-up (12 years), there is no evidence of any recurrence, and she is performing all daily routine activities without any difficulty.

GCTs of the small bones of the hands and feet represent a rare subset, comprising approximately 3–5% of all cases [11]. Within this group, metatarsal GCTs are particularly uncommon and exhibit a more aggressive clinical course. They predominantly occur in the second and third decades of life, with a higher incidence noted in Asian populations, especially in southern India [12]. Our patient, consistent with this demographic trend, presented in her third decade. GCTs in the small bones have been reported to display greater malignant potential compared to those in more common locations. In the early stages, GCTs are frequently asymptomatic, which can delay diagnosis. These lesions are typically solitary but may present as multicentric in 1–2% of cases [13]. Tumor expansion is often rapid and multidirectional, involving cortical destruction and extension into adjacent soft tissues. This behavior is attributed to the secretion of various cytokines by stromal cells, including vascular endothelial growth factor, matrix metalloproteinase-9, and elevated mRNA expression [14]. Histopathologically, GCTs are composed predominantly of mononuclear stromal cells, histiocytes, and multinucleated giant cells formed through cellular fusion [15]. Due to the aggressive local behavior and anatomical constraints in small bones, complete surgical excision can be challenging. Extensive bone destruction and soft-tissue involvement often complicate reconstructive efforts [16]. The recurrence rate in GCTs of the small bones has been reported to range between 25% and 50% [17,18,19]. Biscaglia et al. observed a 30% recurrence rate in a series of 29 cases involving the hand and foot [20], whereas Patel et al. and Yanagisawa et al. reported recurrence rates of 18% and 12.5%, respectively, in their respective series [16,18]. Notably, GCTs in the hand and foot tend to behave more aggressively than those in other skeletal locations [20]. Our patient experienced tumor recurrence within 4 months following initial treatment with curettage and bone grafting – a common outcome in such cases. This prompted reevaluation of the surgical strategy. Differential diagnosis for lytic lesions of the small bones includes aneurysmal bone cysts, non-ossifying fibromas, Brown tumors of hyperparathyroidism, giant cell reparative granulomas, enchondromas, osteosarcomas, and both acute and chronic osteomyelitis, including tuberculous variants [21,22,23,24,25]. GCTs are typically graded radiographically using the Campanacci classification system [26]. Although our patient’s lesion was classified as Grade II, the inherently aggressive nature and high recurrence potential of GCTs in small bones suggest that even lower-grade lesions warrant definitive and aggressive treatment strategies. Several treatment modalities have been proposed, including intralesional curettage with or without bone grafting or polymethyl methacrylate cementation, cryotherapy, chemical adjuvants (e.g., phenol and hydrogen peroxide), ray amputation, wide resection, and reconstruction with vascularized or non-vascularized bone grafts [20,27,28]. However, intralesional curettage alone is associated with recurrence rates of 40–60% [26], while the addition of cryotherapy has been shown to reduce this to 2–25% [27]. The use of pharmacological adjuvants such as bisphosphonates [29] and Denosumab [30] has also been advocated to reduce post-operative recurrence.

In the present case, the tumor recurred rapidly and involved the entire first metatarsal. Following multidisciplinary discussion with the patient, her family, and the tumor board, en bloc resection of the first metatarsal was planned, followed by reconstruction using a vascularized transfer of the second metatarsal and second toe amputation. This technique was selected due to the anatomical proximity of the second metatarsal, which allows for preservation of native vascular supply without the need for complex microvascular anastomosis. In addition, this method minimized donor site morbidity, eliminated the need for secondary incisions, and preserved the base of the second metatarsal to maintain the medial longitudinal arch. The patient has been followed for over 12 years postoperatively and remains asymptomatic, with no clinical or radiological evidence of recurrence. Functional outcomes, as assessed by the American Orthopedic Foot and Ankle Society scoring system [31], showed substantial improvement. The midfoot score improved from 22 preoperatively to 91 postoperatively, and the hallux MTP-interphalangeal score improved from 30 to 87. This case highlights the importance of early recognition and aggressive management of recurrent GCTs in small bones. Vascularized second metatarsal transfer offers a reliable, anatomically favorable, and functionally effective reconstructive option following radical resection of the first metatarsal. Given its long-term durability and excellent functional outcomes, this technique represents a valuable limb-salvage alternative to amputation in appropriately selected patients.

GCTs of the small bones of the hand and foot are rare but notably aggressive, often presenting with a short duration of symptoms and carrying a high risk of early local recurrence and, in some cases, distant metastasis. Due to their locally destructive nature and anatomical constraints, these tumors require prompt and aggressive management. While multiple treatment modalities exist, en bloc resection with limb-preserving reconstruction offers the most effective balance between oncological control and functional preservation – particularly in lesions involving critical weight-bearing areas such as the first metatarsal. Amputation, though oncologically sound, significantly compromises function, especially in the forefoot, and should be reserved for non-reconstructable or extensively invasive cases.

In the present case, vascularized second metatarsal transfer following en bloc resection of the first metatarsal provided excellent long-term oncological and functional outcomes, with minimal donor site morbidity. Based on our experience and extended follow-up, we conclude that this technique represents a reliable, anatomically sound, and functionally effective reconstructive option in the management of recurrent GCT of the first metatarsal.

Recurrent GCT requires aggressive treatment and an appropriate reconstruction method to achieve a good functional outcome.

References

- 1. Murphey MD, Nomikos GC, Flemming DJ, Gannon FH, Temple HT, Kransdorf MJ. Imaging of giant cell tumor and giant cell reparative granuloma of bone: Radiologic-pathologic correlation. Radiographics 2001;21:1283-309. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Campanacci M, Baldini N, Boriani S, Sudanese A. Giant-cell tumor of bone. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1987;69:106-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Lee CH, Espinosa I, Jensen KC, Subramanian S, Zhu SX, Varma S, et al. Gene expression profiling identifies p63 as a diagnostic marker for giant cell tumor of the bone. Mod Pathol 2008;21:531-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Kransdorf MJ, Sweet DE, Buetow PC, Giudici MA, Moser RP Jr. Giant cell tumor in skeletally immature patients. Radiology 1992;184:233-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. O’Keefe RJ, O’Donnell RJ, Temple HT, Scully SP, Mankin HJ. Giant cell tumor of bone in the foot and ankle. Foot Ankle Int 1995;16:617-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Mohan V, Gupta SK, Sharma OP, Varma DN. Giant cell tumor of short tubular bones of the hands and feet. Indian J Radiol 1980;34:14-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Ostrowski ML, Spjut HJ. Lesions of the bones of the hands and feet. Am J Surg Pathol 1997;21:676-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Sneige N, Ayala AG, Carrasco CH, Murray J, Raymond AK. Giant cell tumor of bone. A cytologic study of 24 cases. Diagn Cytopathol 1985;1:111-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Agarwal S, Chawla S, Agarwal S, Agarwal P. Giant cell tumour 2nd metatarsal-Result with en-bloc excision and autologous fibular grafting. Foot (Edinb) 2015;25:265-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Goldenberg RR, Campbell CJ, Bonfiglio M. Giant-cell tumour of bone. An analysis of two hundred and eighteen cases. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1970;52:619-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Hutter RV, Worcester JN Jr., Francis KC, Foote FW Jr., Stewart FW. Benign and malignant giant cell tumors of bone. A clinicopathological analysis of the natural history of the disease. Cancer 1962;15:653-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Reddy CR, Rao PS, Rajakumari K. Giant-cell tumors of bone in South India. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:617-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Ruggieri P, Angelini A, Jorge FD, Maraldi M, Giannini S. Review of foot tumors seen in a university tumor institute. J Foot Ankle Surg 2014;53:282-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Shimizu T, Uehara T, Akahane T, Isobe K, Arai H. Recurrence potential of diffuse-type giant cell tumor in the foot: Radiologic and pathologic features. Foot Ankle Int 2005;26:474-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Werner M. Giant cell tumour of bone: Morphological, biological and histogenetical aspects. Int Orthop 2006;30:484-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Patel R, Parmar R, Agarwal S. Giant cell tumour of the small bones of hand and foot. Cureus 2023;15:e42197. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Oliveira VC, van der Heijden L, van der Geest IC, Campanacci DA, Gibbons CL, van de Sande MA, et al. Giant cell tumours of the small bones of the hands and feet: Long-term results of 30 patients and a systematic literature review. Bone Joint J 2013;95-B:838-45. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Yanagisawa M, Okada K, Tajino T, Torigoe T, Kawai A, Nishida J. A clinicopathological study of giant cell tumor of small bones. Ups J Med Sci 2011;116:265-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Rajani R, Schaefer L, Scarborough MT, Gibbs CP. Giant cell tumors of the foot and ankle bones: High recurrence rates after surgical treatment. J Foot Ankle Surg 2015;54:1141-5. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Biscaglia R, Bacchini P, Bertoni F. Giant cell tumor of the bones of the hand and foot. Cancer 2000;88:2022-32. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Yurdoglu C, Altan E, Tonbul M, Ozbaydar MU. Giant cell tumor of second and third metatarsals and a simplified surgical technique: Report of two cases. J Foot Ankle Surg 2011;50:230-4. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Rosenberg AE, Nielsen GP. Giant cell containing lesions of bone and their differential diagnosis. Curr Diagn Pathol 2001;7:235-46. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Siddiqui YS, Zahid M, Bin Sabir A, Julfiqar. Giant cell tumor of the first metatarsal. J Cancer Res Ther 2011;7:208-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Kamath BJ, Nayak UK, Mahale A, Divakar PM. Rare case of first metatarsal giant cell tumour and its unique reconstruction with double barrel non-vascularized fibular graft. Fuß Sprunggelenk 2023;21:84-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Divakar PM. Rare case of first metatarsal giant cell tumour and its unique reconstruction with double barrel non-vascularized fibular graft. Fuß Sprunggelenk 2023;21:84-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 26. Campanacci M, Giunti A, Olmi R. Metaphyseal and diaphyseal localization of giant cell tumors. Chir Organi Mov 1975;62:29-34. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 27. Ly JQ, Arnett GW, Beall DP. Giant celltumor ofthe second metatarsal. Radiology 2007;245:288-91. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 28. Omlor GW, Lange J, Streit M, Gantz S, Merle C, Germann T, et al. Retrospective analysis of 51 intralesionally treated cases with progressed giant cell tumor of the bone: local adjuvant use of hydrogen peroxide reduces the risk for tumor recurrence. World J Surg Oncol 2019;17:73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 29. Tse LF, Wong KC, Kumta SM, Huang L, Chow TC, Griffith JF. Bisphosphonates reduce local recurrence in extremity giant cell tumor of bone: A case-control study. Bone 2008;42:68-73. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 30. Arulprashanth A, Faleel A, Palkumbura C, Jayarajah U, Sooriyarachchi R. Adjuvant Denosumab therapy following curettage and external fixator for a giant cell tumor of the distal radius presenting with a pathological fracture: A case report. Int J Surg Case Rep 2022;96:107342. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 31. Kitaoka HB, Alexander IJ, Adelaar RS, Nunley JA, Myerson MS, Sanders M. Clinical rating systems for the ankle-hindfoot, midfoot, hallux, and lesser toes. Foot Ankle Int 1994;15:349-53. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]