Retrograde intramedullary nailing for periprosthetic distal femur fractures has fewer mechanical complications but a higher chance of later hardware removal than locked plating.

Dr. Aamir Shahzad, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Tameside and Glossop Integrated Care NHS Foundation Trust, Greater Manchester OL6 9RW, United Kingdom. E-mail: amirshehzad4321@gmail.com

Introduction: Periprosthetic distal femur fractures (PDFF) after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are increasing with the growth of arthroplasty volume and longevity of implants; reported incidences for primary TKA range from ~0.3% to 2.5%, underscoring a clinically meaningful burden. Comparative data suggest both retrograde intramedullary nailing (RIMN) and locked plating (LP) achieve acceptable union with broadly similar complication profiles, but uncertainty persists regarding construct-specific trade-offs.

Materials and Methods: We conducted a retrospective propensity-matched cohort study within the TriNetX U.S. Collaborative Network, a federated platform of de-identified electronic health records from dozens of U.S. health systems. Adult patients (≥50 years) with PDFF around a stable knee prosthesis were identified using International Classification of Disease-10 (ICD-10) diagnosis and current procedural terminology/ICD-10-procedure coding system procedure codes. The index event was the first qualifying fixation – RIMN or LP – with outcomes observed for 365 days post-index. Propensity score matching (1:1, greedy nearest neighbor without replacement) balanced age, sex, and comorbidities (e.g., diabetes, hypertension, cardiovascular, renal, pulmonary, hepatic disease, osteoporosis, obesity, tobacco use, depression, rheumatoid arthritis). Outcomes included revision/re-operation, hardware removal, mechanical implant complications, deep infection, non-union/malunion, re-fracture coding events, and venous thromboembolism (deep vein thrombosis/pulmonary embolism [DVT/PE]). We report risk difference (RD), risk ratio (RR, 95% confidence interval [CI]; P-matching RD P-values), and time-to-event hazard ratios (HR, 95% CI) from Kaplan–Meier/log-rank analyses. TriNetX governance ensures de-identification and standardized analytics.

Results: After matching, 1,152 RIMN patients were compared with 1,152 LP patients with similar baseline characteristics and follow-up (median ~11–12 months). Revision/re-operation within 1 year was uncommon and comparable (1.0% RIMN vs. 1.5% LP; RD−0.4%, P = 0.35; RR 0.71, 95% CI 0.34–1.47; HR 0.77, log-rank P = 0.49). Hardware removal occurred more often after RIMN (6.0% vs. 4.2%; RD + 1.8%, 95% CI 0.0–3.6%; P = 0.046; RR 1.44, 95% CI 1.00–2.06; HR 1.60, log-rank P = 0.012). Mechanical implant complications were less frequent with RIMN (3.6% vs. 5.6%; RD −2.0%, 95% CI −3.7–−0.3%; P = 0.023; RR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.94; HR 0.68, log-rank P = 0.047). Deep infection rates were similar (6.3% vs. 7.4%; RD −1.0%, P = 0.32; RR 0.86, 95% CI 0.64–1.16; HR 0.89, P = 0.48), as were non-union/malunion (5.0% vs. 5.6%; RD −0.5%, P = 0.58; RR 0.91, 95% CI 0.64–1.28; HR 0.94, P = 0.75). DVT (4.6% vs. 6.2%; RD −1.6%, P = 0.097; RR 0.75, 95% CI 0.53–1.06; HR 0.77, P = 0.14) and PE (3.7% vs. 4.4%; RD −0.7%, P = 0.40; RR 0.84, 95% CI 0.57–1.26; HR 0.86, P = 0.46) did not differ significantly. These findings align with prior comparative literature showing broadly similar healing and complication rates between constructs, with nuanced differences by endpoint.

Conclusion: In a large real-world, propensity-matched cohort, RIMN and LP produced comparable 1-year union, infection, thromboembolism, and revision rates for PDFF after TKA. RIMN was associated with fewer mechanical implant failures but a higher frequency of elective hardware removal, reflecting a clinically relevant trade-off. Construct selection should be individualized to prosthesis design, fracture geometry, distal bone stock, and patient priorities. Findings complement prior meta-analyses and multicenter series and support shared decision-making rather than a one-size-fits-all approach.

Keywords: Retrograde intramedullary nailing, Locked plating, Periprosthetic distal femur fracture, Total knee arthroplasty, Propensity score matching, Mechanical implant complications, Hardware removal

Periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur after total knee arthroplasty (TKA) are an increasingly common and challenging complication in the aging orthopedic population [1,2,3,4,5]. The incidence of these fractures has been reported between 0.3% and 2.5% of primary knee replacements [1,2,3], and it continues to rise as more knee arthroplasties are performed and patients live longer with their implants [2,3,4,5]. Such injuries typically occur from low-energy trauma (e.g., simple falls) in elderly patients with risk factors like osteoporosis, rheumatoid arthritis, chronic steroid use, or a notched anterior femoral cortex [1,4]. Management is difficult due to compromised bone stock around the prosthesis and patient frailty, and high rates of adverse outcomes have been reported – including non-union (~9%), fixation failure (~4%), deep infection (~3%), and need for revision surgery (~13%) in prior case series [5,6]. Moreover, periprosthetic distal femur fractures (PDFF) carry substantial mortality; one population-based study noted approximately 15% mortality at 1 year post-fracture [7], underlining the importance of optimizing treatment. When the knee prosthesis is well-fixed (Rorabeck type I or II fractures), surgical fixation of the distal femur is the preferred management to restore knee function and allow early mobilization [4,8]. The two predominant fixation strategies are retrograde intramedullary nailing (RIMN) and locked plating with a lateral distal femur . Each approach has theoretical advantages. A RIMN is a load-sharing device aligned with the femoral axis, which provides better distribution of stress and often allows for stable fixation with less extensive exposure of bone, potentially permitting earlier weight-bearing [8]. By contrast, locking plates can achieve secure fixation even in very distal fracture fragments by using multiple screws in the condyles, which is advantageous when the fracture is near the prosthetic flange or if the intramedullary (IM) path is obstructed [4,8]. However, locking plate constructs are eccentrically loaded and can be very stiff, potentially increasing the risk of non-union or hardware failure in the absence of bone healing [6,9]. Biomechanical studies have indicated nails may tolerate repetitive loads better, whereas clinical outcomes between the two methods have remained a topic of debate [5,6,9,10]. Several retrospective studies and meta-analyses have compared IM nailing versus plating for distal femur fractures (including periprosthetic cases), but results have varied. Early reports suggested no clear superiority, with similar union rates and overall complication profiles for nails and plates [5,6,10]. For example, a 2017 meta-analysis of periprosthetic supracondylar fractures found no significant difference in outcome between locked compression plating and retrograde nailing [5]. On the other hand, some evidence has hinted that modern retrograde nails might have an edge in specific outcomes: One multicenter study of very distal periprosthetic fractures noted a lower (though not statistically significant) reoperation rate for nails (8% vs. 16% for plates) and a higher likelihood of immediate weight-bearing permission [11]. Similarly, Meneghini et al. observed that locked plate fixation had nearly double the failure (non-union or hardware failure) rate of IM nails (19% vs. 9%) in PDFFs, despite using more distal screws, suggesting a trend toward better reliability with nails [9]. Overall, the current literature indicates both techniques can achieve acceptable outcomes, but each may carry distinct risks: Nails might facilitate earlier mobilization and have a lower risk of catastrophic failure, whereas plates might be necessary for the most distal fracture patterns or certain prosthetic designs [5,6,8,10].

Study design

We performed a retrospective cohort study comparing two surgical treatments for PDFFs after TKA. The study design and reporting follow the STROBE guidelines for observational studies. Patients were divided into two cohorts based on the fixation method (retrograde IM nailing vs. plate osteosynthesis) and were compared for various outcomes over a 1-year follow-up. This investigation was conducted using de-identified data from a large multicenter electronic health record network and was exempt from institutional review board review.

Data source

We utilized the TriNetX® US Collaborative Network, a federated health research platform that aggregates de-identified clinical data from 68 healthcare organizations in the United States. The platform allows real-time querying of patient records and supports cohort analyses with built-in propensity score matching (PSM) and outcomes analysis. For this study, we identified patients and outcomes through diagnoses and procedure codes recorded in the electronic medical records. The data included demographics, diagnosis codes, procedure codes, and clinical outcomes. An index event and observation windows were defined for each cohort to capture outcomes within 1 year following the initial fracture fixation. No direct patient-identifying information was accessible, and all analyses were done on aggregate summary data.

Participants (cohort selection)

Inclusion criteria

We included patients aged 50 years and older who had a documented periprosthetic fracture of the distal femur around a knee prosthesis. This was defined by the International Classification of Disease-10 (ICD-10) clinical modification diagnosis codes M97.11, M97.12, or M97.1 (periprosthetic fracture around internal prosthetic right knee, left knee, or unspecified knee joint). Cohort 1 (RIMN) consisted of patients who underwent RIMN fixation for the distal femur fracture, and Cohort 2 (plate fixation) consisted of patients who underwent plate (open reduction and internal fixation with a lateral locking plate or similar device) for the fracture. To ensure the fixation was for the periprosthetic fracture of interest, the procedure had to occur within 3 months after the fracture diagnosis. In the TriNetX query, we required an event relationship where a qualifying fixation procedure occurred within 1 day before or up to 3 months after the PDFF diagnosis. This captured patients who received fracture fixation shortly after the fracture event (allowing a 3-month window). We used current procedural terminology (CPT) and ICD-10-procedure coding system (ICD-10-PCS) procedure codes to define each type of fixation. For RIMN, examples of codes included CPT 27509 (percutaneous skeletal fixation of distal femur fracture) and ICD-10-PCS 0QSB06Z/0QSC06Z (open insertion of IM device in right/left distal femur). For plate fixation, examples included CPT 27507 (open treatment of femoral shaft fracture with plate/screws), CPT 27513 (open treatment of distal femur fracture with intercondylar extension, with internal fixation), CPT 27514 (open treatment of distal femoral condyle fracture, with internal fixation), and equivalent ICD-10-PCS codes for open internal fixation of the distal femur. Patients were assigned to one of the two cohorts based on the first qualifying fixation procedure recorded. Patients were excluded if their index event occurred ≥20 years before the query date (to ensure contemporary data; in practice, no patients were excluded for this reason in our analysis). We also excluded patients lacking at least 1 year of potential follow-up after the index surgery (i.e., if no records beyond the index were available) to allow assessment of 1-year outcomes.

Index event and follow-up

The index event was defined as the date of the fracture fixation procedure (nailing or plating) for each patient. Follow-up for outcomes began the day after the index event and continued for 365 days (1 year) post-surgery. Outcomes occurring within this 1-year observation window (day 1–day 365 after surgery) were captured for analysis. Patients were censored at the time of the outcome event or at 365 days, whichever came first. All outcome events were defined by diagnostic or procedure codes occurring in the follow-up period, as detailed below.

Outcomes assessed

We examined a range of adverse outcomes within 1-year post-fixation, chosen a priori based on clinical relevance. Outcomes were categorized into surgical, mechanical, infectious, fracture-healing, thromboembolic, and refracture events. Table 1 lists the specific codes used to define each outcome. The outcomes of interest were:

Surgical outcomes: (1) Revision or re-operation involving the distal femur or knee prosthesis (e.g., revision arthroplasty or repeat open fixation), and (2) Removal of fixation hardware (surgical removal of nail, plate, or screws; e.g., CPT 20680 removal of deep implant).

Mechanical complications: (3) Mechanical complications of implant – failure or loosening of the internal fixation or prosthesis (e.g., ICD-10 T84.03, T84.04 for loosening or breakage of internal joint prosthesis).

Infectious complications: (4) Deep infection involving the hardware or joint – periprosthetic joint infection or deep surgical-site infection (e.g., ICD-10 T84.5X: infection due to internal joint prosthesis).

Fracture healing outcomes: (5) Non-union or malunion of the distal femur fracture – lack of fracture healing or healed in poor alignment (e.g., ICD-10 codes M84.1X/M84.0X for disorders of bone continuity).

Re-fracture events: (6) New periprosthetic fracture of the distal femur – a new fracture event around the knee prosthesis after the index surgery (identified by a repeat diagnosis of PDFF, ICD-10 M97.1X, during follow-up).

Thromboembolic events: (7) Deep vein thrombosis (DVT) – acute thrombosis of the lower extremity deep veins (ICD-10 I82.4X), and (8) Pulmonary embolism (PE) (ICD-10 I26.XX).

Each outcome was counted if it occurred at least once in the 1-year post-index period. In patients with multiple occurrences of an outcome (e.g., multiple DVTs), only the first occurrence was considered for time-to-event analysis. Outcomes were mutually not exclusive (patients could experience more than one type of complication).

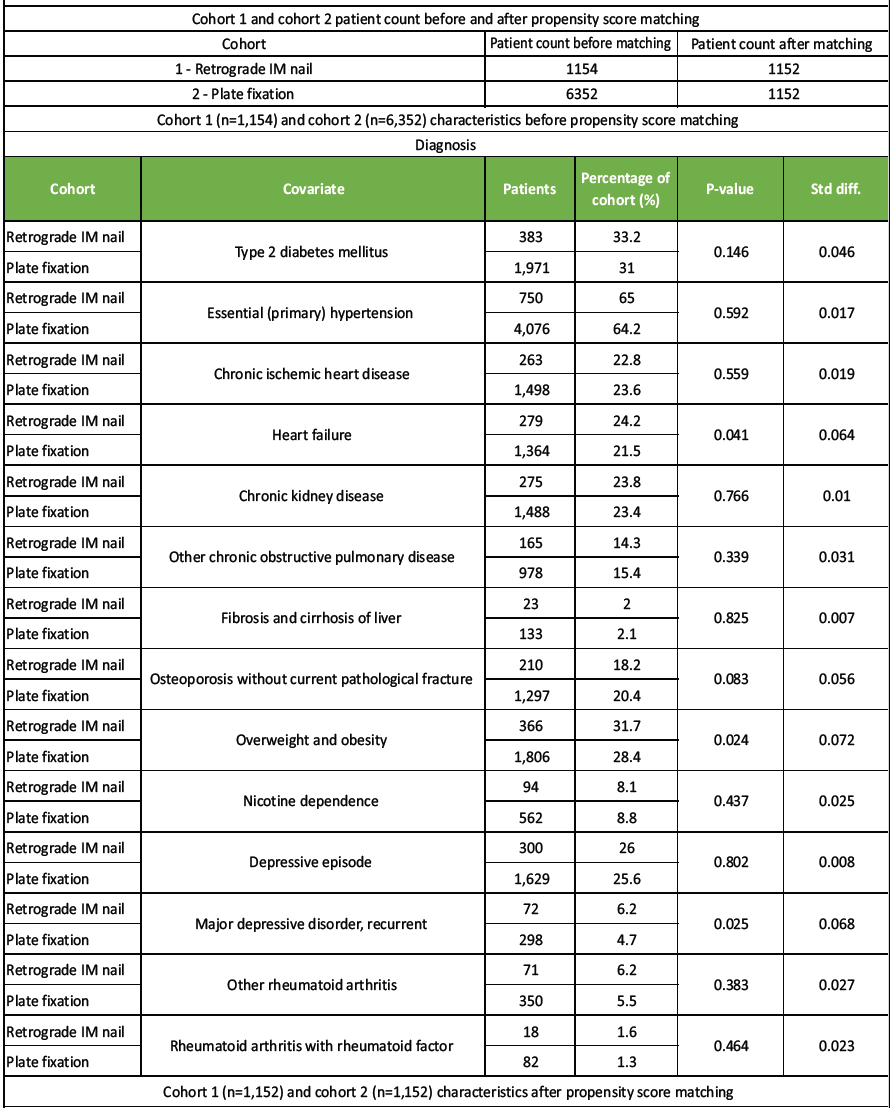

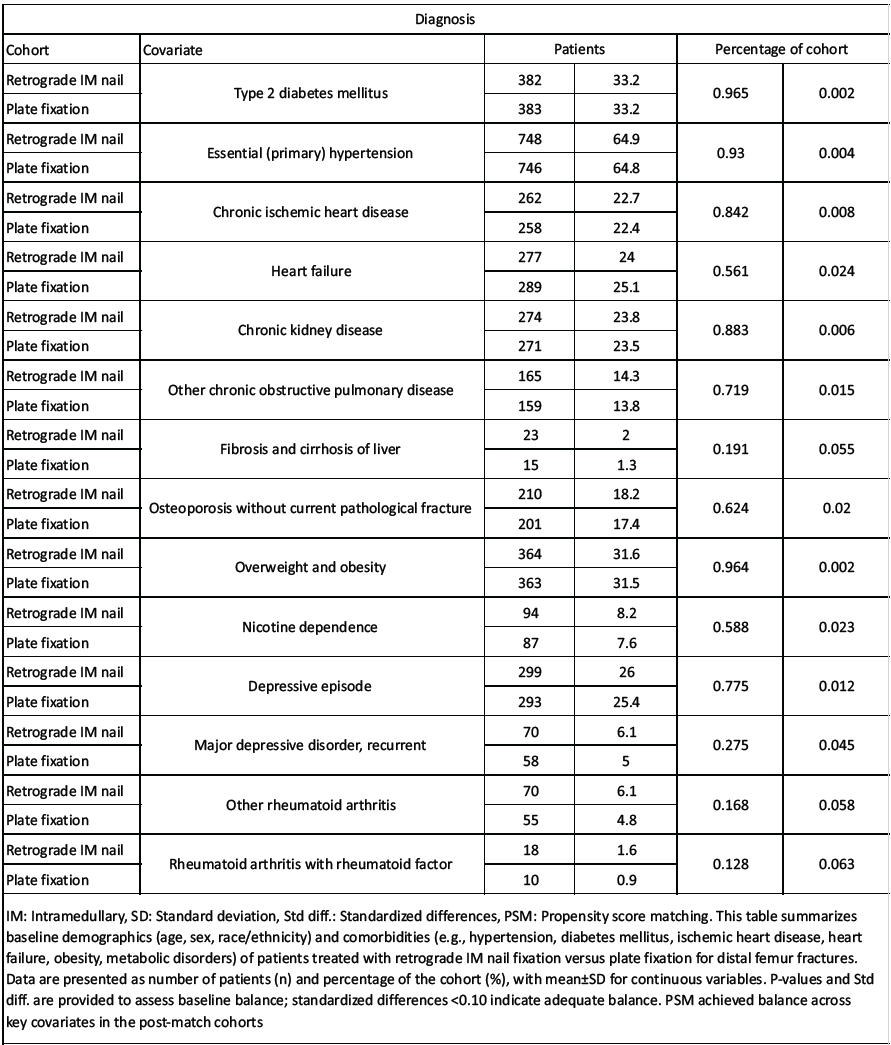

Table 1: Baseline demographics and clinical characteristics of patients undergoing retrograde intramedullary nail versus plate fixation before and after propensity score matching

PSM

Because treatment assignment (nail vs. plate) was not randomized, we employed 1:1 PSM to reduce confounding. The two cohorts were matched for baseline characteristics using the TriNetX platform’s greedy nearest-neighbor algorithm (with no replacement). The propensity score model included demographic and comorbidity variables selected a priori based on clinical relevance to outcomes. We matched on age and sex (female vs. male), as well as the following comorbid conditions (coded as presence of diagnosis before the index event): Type 2 diabetes mellitus, hypertension, coronary artery disease (chronic ischemic heart disease), heart failure, chronic kidney disease, chronic lung disease (e.g., chronic obstructive pulmonary disease [COPD]), chronic liver disease (cirrhosis), osteoporosis, obesity, tobacco use (nicotine dependence), depression (major depressive disorder), and rheumatoid arthritis. These conditions were identified through ICD-10 codes (for example, E11 for diabetes, I10 for hypertension, I25 for ischemic heart disease, I50 for heart failure, N18 for CKD, J44 for COPD, K74 for cirrhosis, M81 for osteoporosis, E66 for obesity, F17 for nicotine dependence, F32/F33 for depression, M05/M06 for rheumatoid arthritis). The matching caliper and specifics followed TriNetX default settings to achieve balance.

After PSM, the two cohorts were well-balanced on all included covariates. Table 1 shows the cohort characteristics before and after matching. Before matching, the plate fixation group was larger and had some minor differences in comorbidity rates (e.g., heart failure and obesity were slightly more common in the nail cohort) – however, none of these differences exceeded a standardized difference of 0.10. Matching resulted in 1,152 patients in each group, drawn from the original 1,154 nail patients and 6,352 plate patients. Post-match, there were no significant differences in baseline demographics or comorbidities between the nail and plate cohorts (all P > 0.5; standardized differences <0.05 for all variables). This indicates that the PSM achieved a good balance. The mean age of patients was in the early 70s, and approximately two-thirds of each cohort were female (no significant sex difference after matching). The median follow-up time after surgery was 11.0 months for the IM nail group and 12.0 months for the plate group (interquartile range ~9–12 months in both; median 336.5 vs. 365 days), reflecting that most patients had data nearly up to 1-year post-index.

Statistical analysis

We compared the incidence of each outcome between the matched cohorts. For each outcome, we computed the risk (cumulative incidence) in each group over the 1-year period and the risk difference (RD) and risk ratio (RR) with 95% confidence intervals (CIs). These measures were calculated using the TriNetX “Compare Outcomes” analytics, which applies a z-test for differences in proportions and provides CIs for RD and RR. We also conducted time-to-event analysis for each outcome using Kaplan–Meier methods. Patients without the outcome were censored at 365 days. We report the hazard ratio (HR) for the nail vs. plate cohort (an HR <1 indicates lower hazard with nailing, HR >1 indicates higher hazard with nailing) along with 95% CIs, and the log-rank test P-value for the difference in survival curves. The proportional hazards assumption was checked; no significant violations were detected for any outcome (we used the log–log survival plots and TriNetX’s test of proportionality when available). All tests were two-sided, and P < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed within the TriNetX platform (which automatically accounts for the matched design in the variance calculations). The results are presented as adjusted comparisons between the propensity-matched cohorts.

Patient characteristics

Initially, 1,154 patients from the retrograde nail cohort and 6,352 patients were included from the plate fixation cohort. After propensity matching, 1,152 patients who underwent RIMN were compared with 1,152 patients who underwent plate fixation for PDFFs. The two matched cohorts had very similar baseline characteristics (Table 1). The mean age was approximately 72 years in both groups, with no significant difference. Women comprised the majority of patients in both the nail and plate cohorts (70% in each), reflecting the typical demographic for osteoporotic periprosthetic fractures; the sex distribution was balanced between groups. Comorbid conditions were well-matched: For example, the prevalence of diabetes mellitus was 33.2% in both groups, hypertension about 65% in both, and osteoporosis 18% in both (all P > 0.9 after matching). Table 1 summarizes key baseline comorbidities and shows no statistically significant differences post-matching. The median follow-up duration was 11–12 months in both cohorts, with an interquartile range spanning approximately 8–12 months. Thus, the cohorts were comparable in terms of baseline risk factors and observed for a similar length of time, providing a balanced foundation for outcome comparison.

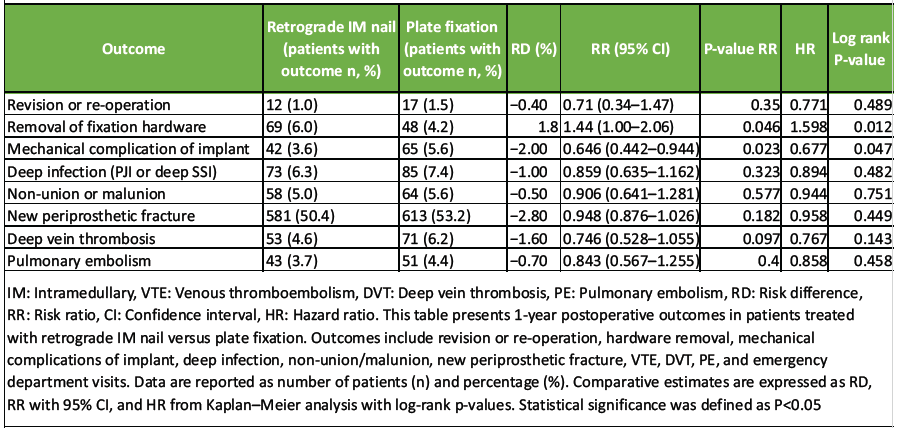

Surgical outcomes (revision surgery and hardware removal)

Revision or re-operation: This outcome was relatively rare in both groups. Only 12 patients (1.0%) in the nail cohort and 17 patients (1.5%) in the plate cohort required a revision surgery or major re-operation on the distal femur/knee within 1 year. This difference was not statistically significant. The absolute RD was −0.4% (nail vs. plate), and the RR was 0.71 (95% CI 0.34–1.47) in favor of nails (indicating a non-significant trend toward fewer revisions with nailing) (Table 2). The P-value for the difference was 0.35. Consistently, the Kaplan–Meier analysis showed no significant difference in revision-free survival between groups (HR = 0.77 for nail vs. plate, log-rank P = 0.49; Table 2). In summary, the rate of revision surgery was low and did not differ meaningfully between the two fixation methods.

Table 2: One-year clinical outcomes in patients undergoing retrograde intramedullary nail versus plate fixation after distal femur fractures

Removal of fixation hardware

In contrast, we found a significant difference in the need for hardware removal procedures. The IM nail group had 69 patients (6.0%) undergo removal of hardware (typically nail or locking screw removal) within 1 year, compared to 48 patients (4.2%) in the plate group. This corresponds to an absolute risk increase of +1.8% associated with nails relative to plates (RD = +1.8%, 95% CI 0.0–3.6%). The difference was statistically significant (P = 0.046). Patients treated with nail fixation were about one and a half times as likely to require subsequent hardware removal as those treated with plating (RR = 1.44, 95% CI 1.00–2.06). The time-to-event analysis similarly showed a higher hazard of hardware removal in the nail cohort: HR = 1.60 (95% CI ~1.11–2.31), with a significant divergence in removal-free survival curves (P = 0.012 by log-rank test) (Table 2). In practical terms, hardware removal (often elective nail removal or exchange) occurred more frequently after retrograde nailing than after plate fixation in the 1st year.

Mechanical complications

Mechanical complications of the implant (such as hardware failure or loosening) were less common with IM nailing compared to plating. In the nail cohort, 42 patients (3.6%) experienced a mechanical complication of the implant, versus 65 patients (5.6%) in the plate cohort during 1-year follow-up. This difference in favor of nails (an absolute reduction of −2.0%) was statistically significant (P = 0.023). The RR for mechanical complications was 0.65 (95% CI 0.44–0.94), indicating a 35% relative risk reduction with retrograde nailing as compared to plating. Kaplan–Meier analysis demonstrated significantly lower cumulative incidence of mechanical failure in the nail group: The hazard of mechanical complication was roughly 33% lower with nails (HR = 0.68, 95% CI ~0.46–1.00), and the log-rank P = 0.047 (Table 2). Thus, nails were associated with significantly fewer mechanical implant problems at 1 year than plates. In the plate group, these mechanical issues likely included plate or screw breakage, fixation loosening, or failure of union leading to hardware stress, whereas the lower rate in the nail group suggests a biomechanical advantage of the load-sharing IM device in this context.

Infectious complications

The rate of deep infection (periprosthetic joint infection or deep surgical-site infection involving the implant) was similar between the two treatments. In the nail cohort, 73 patients (6.3%) developed a deep infection, compared to 85 patients (7.4%) in the plate cohort. This yields an absolute difference of –1.0% (favoring nails), which was not statistically significant (RD −1.0%, 95% CI −3.1–+1.0%; P = 0.32). The relative risk of infection with nailing was 0.86 (95% CI 0.64–1.16) compared to plating, but this did not reach significance. The Kaplan–Meier analysis likewise showed no significant difference in infection-free survival (HR = 0.89 for nail vs. plate, log-rank P = 0.48). In other words, approximately 7% of patients in both groups experienced a deep infection complication within 1 year, and the choice of nail versus plate did not significantly impact this risk (Table 2).

Fracture healing outcomes (non-union/malunion)

We observed no significant difference between nails and plates in terms of fracture healing complications. The incidence of non-union or malunion of the distal femur fracture was 5.0% in the nail fixation group (58 patients) and 5.6% in the plate fixation group (64 patients). This 0.6% absolute difference was not statistically significant (RD = −0.5%, 95% CI −2.3–+1.3%; P = 0.58). The RR was 0.91 (95% CI 0.64–1.28) for nails versus plates, again indicating no meaningful difference. At 1 year, roughly one in twenty patients in each cohort had evidence of non-union (failure of the fracture to heal) or malunion (healed with deformity). The hazard of non-union/malunion did not differ appreciably (HR ~0.94, log-rank P = 0.75). Therefore, both fixation methods resulted in comparable fracture healing outcomes by 12 months (Table 2).

Re-fracture events

We tracked any new periprosthetic fracture of the distal femur (re-fracture) during the follow-up period. The incidence of new fracture events was substantial and did not significantly differ between cohorts: 50.4% in the nail group (581 patients) versus 53.2% in the plate group (613 patients) had at least one new diagnosis of PDFF during the year after the index surgery. The nail group had a slightly lower rate (by 2.8 percentage points), but this difference was not statistically significant (RD = –2.8%, 95% CI –6.9% to +1.3%; P = 0.18). The RR for re-fracture with nails was 0.95 (95% CI 0.88–1.03), and the HR was 0.96 (log-rank P = 0.45), none of which indicates a significant divergence (Table 2). It is noteworthy that roughly half of the patients appeared to have a “recurrent” fracture code within a year; this high percentage likely reflects repeated imaging or encounter diagnoses for the original fracture (or fracture non-union) rather than true independent new fracture events in all cases. In any case, there was no evidence that one fixation method protected against (or predisposed to) subsequent fracture more than the other.

Thromboembolic events (DVT and PE)

DVT: The occurrence of post-operative DVT was not significantly different between the two groups. In the nail cohort, 53 patients (4.6%) had a DVT, versus 71 patients (6.2%) in the plate cohort. Although numerically lower with nails, this 1.6% absolute difference did not reach statistical significance (RD = −1.6%, 95% CI −3.4–+0.3%; P = 0.097). The relative risk of DVT for nail versus plate was 0.75 (95% CI 0.53–1.06). Time-to-event analysis similarly showed a non-significant trend favoring nails: HR = 0.77, with log-rank P = 0.14 (Table 2).

PE

Similarly, PE rates were comparable between groups. Forty-three patients (3.7%) in the nail group and 51 patients (4.4%) in the plate group experienced a PE within 1 year. This difference of 0.7% was not significant (RD = −0.7%, 95% CI −2.3–+0.9%; P = 0.40). The RR was 0.84 (95% CI 0.57–1.26) and HR = 0.86 for nails versus plates, with no significant separation in the Kaplan–Meier curves (log-rank P = 0.46). Thus, the risk of post-operative thromboembolic events (DVT or PE) was low in both cohorts (on the order of 5% or less) and did not differ in a statistically significant way based on fixation method. Overall, aside from the differences in hardware removal and mechanical failure rates noted above, all other outcomes were statistically similar between retrograde nailing and plating. Table 2 provides a summary of all outcome event rates in each group, along with the absolute RDs, relative risks, and HR with CIs.

In this large comparative analysis of 1,152 patients treated with RIMN versus 1,152 patients treated with locked plating (matched on baseline characteristics), we found that overall clinical outcomes at 1 year were comparable between the two fixation methods, with some important differences in specific complications. Consistent with our expectations, rates of fracture union and deep infection were not significantly different between nails and plates in our cohort. The incidence of non-union/malunion was around 5% in both groups, and deep periprosthetic joint infection occurred in approximately 6–7% of cases, with no statistically significant advantage observed for either fixation strategy. These findings align with prior studies reporting equivalent healing rates for nails versus plates in PDFFs [5,6,10]. We also noted that the overall re-operation rate for major complications (excluding elective hardware removal) was low and similar between groups (~1% in nails vs. 1.5% in plates needed revision or unplanned reoperation for union or infection, P > 0.3). This suggests that when the prosthesis is stable and appropriate fixation is achieved, both modern IM nails and locking plates can successfully stabilize these fractures in the majority of patients. Despite these general similarities, our analysis identified two notable differences. First, mechanical implant complications were significantly less frequent in the nail group. We observed a mechanical failure (implant-related complication) rate of 3.6% with retrograde nails versus 5.6% with locking plates, corresponding to a 2.0% absolute risk reduction in favor of nails (95% CI 0.3–3.7%, P = 0.023). This category included hardware failure, such as implant breakage or loosening. The lower mechanical complication rate with nails is consistent with the notion that an IM nail, being a load-sharing device aligned with the femoral axis, is less prone to bending stresses that can lead to plate or screw breakage [4,8]. In our data, locking plates had nearly twice as many hardware failures as nails, echoing Meneghini et al.’s report, where plating failures were double those of nail fixation [9]. Second, we found that symptomatic hardware requiring removal was significantly more common in the nail group. By 1 year, 6.0% of patients with retrograde nails had undergone removal of hardware (most often due to knee pain or irritation from the nail or interlocking screws), compared to 4.2% of plate patients (RD +1.8%, P = 0.046). Notably, these elective hardware removals were the only type of reoperation that was more frequent with nails. In fact, other authors have recognized this issue to the extent of excluding elective nail removal from their primary outcome analyses [11]. The higher rate of hardware removal in our nail cohort likely reflects knee pain caused by the nail or distal locking screws abutting the prosthetic joint and surrounding soft tissues. This finding highlights a trade-off: Although mechanical failure was rarer with nails, patients often experienced anterior knee discomfort or impingement from the nail, leading to secondary procedures for hardware removal. By contrast, lateral plates, which lie external to the femur, less frequently necessitated removal (though plate irritation of the iliotibial band can also occur in some cases [4,8]). Importantly, no significant differences were observed in other adverse outcomes such as thromboembolic events. The incidence of DVT and PE in the 1st year was low in both groups (on the order of 4–6%) and did not differ statistically between nails and plates. We did note a non-significant trend toward fewer DVTs after nailing (4.6% vs. 6.2%, P ≈ 0.10) and fewer PEs (3.7% vs. 4.4%, P > 0.3), but our study was not powered to detect small differences in these complications. These trends could hypothetically be related to earlier mobilization in the nail group, though we cannot conclude this definitively. In addition, the occurrence of a second ipsilateral periprosthetic fracture event within 1 year was observed in both cohorts (~50% of patients had a repeat coded fracture event, likely reflecting ongoing care or coding of the index fracture rather than true new fractures), with no meaningful difference between groups. Overall, our key results indicate that both treatment modalities are effective for managing PDFFs, but IM nailing provided a more forgiving mechanical environment (fewer implant failures) at the cost of a slightly higher need for subsequent elective hardware removal for symptom relief. Our findings are largely in agreement with the existing literature and provide nuanced insight given the relatively large sample size and matched cohort design. Prior systematic reviews focusing on PDFFs have concluded that locking plate fixation and retrograde nailing offer comparable outcomes in terms of union and overall complication rates [5,6,10]. The results of our study reinforce this equivalence in the broad sense – neither method was dramatically superior in achieving fracture healing or avoiding major complications like deep infection. This parity likely reflects that both nails and plates, when applied in appropriate scenarios, can provide sufficient stability for these fractures to heal. In practice, surgeons often choose the implant based on fracture geometry and prosthesis type: For fractures very close to the prosthetic joint line or with a closed-box prosthesis (where nail entry is obstructed), plates are favored, whereas for fractures allowing a nail (prosthesis with an open box and enough distal bone stock), nails are an attractive option. Our results support the notion that surgeons can expect similar healing success with either approach as long as the chosen implant is suitable for the fracture pattern and implant constraints [4,8]. The difference in mechanical failure rates between constructs is an important point of interpretation. The significantly lower incidence of hardware failure with nails is consistent with biomechanical expectations. A locked plate anchored to the lateral cortex experiences high bending moments, especially in osteoporotic bone or if the fracture is slow to unite. Such stress can cause screw pull-out or plate breakage if union is delayed (so-called “fatigue failure” of the plate). In contrast, a well-seated IM nail places less eccentric stress on the bone-implant interface; the nail acts as an internal splint along the weight-bearing axis, sharing load across the fracture site [4,8]. This likely explains why in our series and others, plates showed a trend toward more implant failures. For instance, Meneghini et al. observed more than double the non-union/delayed union rate with plates compared to nails (19% vs. 9%) in a smaller cohort, although their sample size did not reach statistical significance [9]. Our study, with larger numbers, confirms that nails confer a modest but real advantage in reducing fixation failure. This suggests that whenever fracture anatomy and prosthesis design allow for IM nailing, it may provide a more robust construct against repetitive loading. It is worth noting that in our data, the HR for “mechanical complication” favored nails (~0.65), meaning nails had roughly 35% lower hazard of failure relative to plates over the 1-year period. On the other hand, the higher rate of hardware removal with nails illuminates the patient experience and implant-related irritation that is not captured by pure union/failure statistics. Retrograde nails require entry through the intercondylar notch of the femur, which may protrude near the joint and can irritate intra-articular structures or surrounding soft-tissue, sometimes causing chronic anterior knee pain. In addition, distal locking screws in nails traverse the femoral condyles and can impinge on medial soft tissues if too long [4,8]. It is telling that in the multicenter study by Van Rysselberghe et al., elective removal of symptomatic hardware was deliberately excluded from their primary outcome, implicitly acknowledging that nails often necessitate later removal for symptoms [11]. Our finding of ~6% symptomatic hardware removal with nails versus ~4% with plates, though seemingly a small difference, is clinically meaningful – it represents a subset of patients requiring an additional surgical procedure (often an outpatient surgery to remove the nail or screws) primarily for pain relief. In contrast, lateral locking plates, being lower-profile along the femoral shaft (aside from screw tips), tend to be better tolerated once the fracture heals; plate irritation of the iliotibial band can occur, but many patients do not require plate removal unless it causes specific discomfort on activity [4,8]. This aspect highlights that patient-centric outcomes (like pain and implant prominence) must be considered alongside purely mechanical outcomes. Surgeons should counsel patients that an IM nail might offer a better chance of avoiding catastrophic hardware failure or repeat fracture, but it may more frequently lead to minor secondary procedures for hardware removal if the nail becomes bothersome. Another interpretative point is the trend toward fewer thromboembolic events with nails, although not statistically significant. One plausible explanation is that patients treated with nails might have been mobilized earlier postoperatively. In our matched analysis, we did not directly measure time to weight-bearing, but other studies have documented that surgeons are more likely to allow immediate or earlier weight-bearing with retrograde nails than with plates [8,11]. In the series by Van Rysselberghe et al., 45% of nail-treated patients were allowed weight-bearing as tolerated immediately, compared to only 9% of plate-treated patients [11]. Early mobilization could potentially reduce venous stasis and lower DVT risk, which might explain the slightly lower DVT rate we observed in the nail group. Furthermore, at final follow-up, a higher proportion of nail patients in that study were ambulatory without assistive devices (35% vs. 18% for plates) [11], suggesting nails may facilitate better functional recovery in some cases. While our data cannot conclusively prove this benefit, it aligns with the idea that IM nailing may enable more aggressive rehabilitation due to the inherent stability of the load-sharing construct. Early weight-bearing is often critical in this mostly elderly population to prevent complications of immobility (such as DVT, pulmonary issues, or deconditioning). Conversely, with very distal fractures fixed by plates, surgeons sometimes delay full weight-bearing to protect the fixation, given the risk of plate bending or failure. Future prospective studies focusing on functional outcomes and rehabilitation metrics would be valuable to confirm whether nails indeed confer an advantage in early mobilization and functional independence.

Generalizability

Our study leveraged a large real-world dataset from 68 healthcare organizations, which enhances the generalizability of the findings to contemporary practice in similar health systems. The results should be applicable to adult patients (predominantly older adults) with PDFFs around stable knee arthroplasties, managed in tertiary care or community hospital settings with modern implants. Both academic and community hospitals contributed data, and the consistency of results across this broad sample suggests that the conclusions are not limited to a single center’s technique or protocol. The use of a federated health record network (TriNetX) means our findings reflect average outcomes across various surgeons and institutions, increasing external validity. That said, generalisability is bounded by the inclusion criteria: we only analyzed fractures treated with internal fixation; cases requiring acute distal femur replacement (often chosen for highly comminuted fractures or loose prostheses) were not included. Thus, our conclusions apply to the population of fractures where a decision between nail and plate is being made (i.e., the prosthesis is well-fixed and fracture fixation is deemed feasible). In addition, all patients in our cohorts were managed in the United States healthcare context, so results may differ in regions with different implants or rehabilitation practices. Considering technological advancements, it is worth noting that both nail and plate devices continue to evolve. The nails used in recent years often have improved distal locking options (including multiplanar and hybrid locking screws) and designs accommodating periprosthetic anatomy [8]. Plates, too, have evolved with variable-angle locking screws and improved contouring. Our timeframe (patients treated up to 2025) captures outcomes with these modern devices, supporting the relevance of our findings for current-generation implants. We also believe our results are relevant irrespective of specific implant brands, given the large scale; no single manufacturer’s device would dominate such a broad dataset. In summary, our conclusions can likely be generalized to most clinical scenarios where an orthopedic surgeon is choosing between a RIMN and a locking plate for a distal femur fracture above a total knee replacement, assuming the knee component is stable. The balance of risks (mechanical failure vs. hardware irritation) observed should inform surgical decision-making and patient counseling in these cases.

In patients with PDFFs treated after TKA, RIMN and locked plating achieve broadly similar outcomes in union rate, infection, and major re-operation over 1 year. IMN offers a lower risk of mechanical implant failure, whereas plate fixation results in somewhat fewer elective hardware removals. Although symptomatic hardware removal is more frequent after nailing, the trade-offs suggest that when prosthesis design and fracture geometry permit, IMN may provide a more favorable mechanical environment without compromising healing or increasing serious complications. These findings support tailoring surgical decisions to individual patient anatomy, distal bone stock, prosthesis stability, and patient comfort, rather than assuming a universally superior method. Future prospective studies should evaluate longer-term functional results, patient-reported outcomes, and the effect of early weight-bearing protocols to optimize management for this challenging fracture population.

Limitations

This study is limited by its retrospective, observational design using de-identified electronic health record data, which constrains access to clinical details such as fracture morphology, prosthetic stability, bone quality, surgeon technique, and patient functional status, all of which could influence outcomes. Although we used PSM to balance observed covariates, unmeasured confounding likely remains, especially for factors that are not coded. Outcome ascertainment depends on diagnostic and procedure codes, so minor events, outpatient treatments, or issues managed outside participating health systems may be under-reported or misclassified. The 1-year follow-up period may not capture late complications such as delayed implant failure or malalignment. Variability in surgical practice, implants, and postoperative protocols across institutions may introduce heterogeneity, and the use of aggregate rather than detailed patient-level data limits subgroup or interaction analyses. Finally, the necessity to equate P-values for RRs with those for RDs and inability to fully verify proportional hazards assumptions may attenuate the precision of some statistical estimates.

While both and locked plating yield similar rates of fracture union, infection, and major revisions at 1-year follow-up in matched cohorts, the choice of fixation method affects specific complication risks. Retrograde nailing offers a significant advantage in mechanical reliability, with fewer implant failures; however, it carries a higher likelihood of symptomatic hardware removal, which must be weighed in patient counseling. For outcomes where no statistical difference was observed (non-union, malunion, thromboembolism, deep infection), patient anatomy (e.g., distal bone stock, prosthesis design), along with surgeon preference and risk profile, should guide fixation method selection rather than assuming one technique is superior across all cases.

References

- 1. McGraw P, Kumar A. Periprosthetic fractures of the femur after total knee arthroplasty. J Orthop Traumatol 2010;11:135-41. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Caterini A, De Maio F, Marsilio A, Periprosthetic distal femoral fractures after total knee arthroplasty. Acta Biomed 2023;94:e2023125. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Wallace SS, Beauchamp CP, Dunbar MJ. Periprosthetic fractures of the distal femur after total knee arthroplasty: Plate verus nail fixation-review. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2017;103 8 Suppl:S33-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Rhee SJ, Lee JK, Lee S. Femoral periprosthetic fractures after total knee arthroplasty: A surgically oriented classification and management review. Clin Orthop Surg 2018;10:135-44. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Shin YS, Kim HJ, Lee DH. Similar outcomes of locking compression plating and retrograde intramedullary nailing for periprosthetic supracondylar femoral fractures following total knee arthroplasty: A meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2017;25:2921-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Aggarwal S, Rajnish RK, Kumar P, Srivastava A, Rathor K, Haq RU. Comparison of outcomes of retrograde intramedullary nailing versus locking plate fixation in distal femur fractures: A systematic review and meta-analysis of 936 patients in 16 studies. J Orthop 2022;36:36-48. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Miettinen S, Sund R, Törmä S, Kröger H. How often do complications and mortality occur after operatively treated periprosthetic proximal and distal femoral fractures? A register-based study. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2023;481:1940-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. AO Surgery Reference. Retrograde Nailing and Plate Fixation for Periprosthetic Distal Femur Fractures (online surgical reference). Available from: https://surgeryreference.aofoundation.org [Last accessed on August, 2025]. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Meneghini RM, Keyes BJ, Reddy KK, Maar DC. Modern retrograde intramedullary nails versus periarticular locked plates for supracondylar femur fractures after total knee arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2014;29:1478-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Howard A, Carter T, MacDonald R. Retrograde intramedullary nailing or locked plating for distal femoral fractures: Outcomes in a contemporary cohort. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2024;34:1397-406. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Van Rysselberghe NL, Seltzer R, Lawson TA, Kuether J, White P, Grisdela P Jr., et al. Retrograde intramedullary nailing versus locked plating for extreme distal periprosthetic femur fractures: A multicenter retrospective cohort study. J Orthop Trauma 2024;38:57-64. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]