Robotic-arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty (RA-TKA) ensures high bone resection accuracy, providing improvement over conventional methods. This enhanced precision helps preserve bone stock, which is crucial for future revision surgeries and long-term joint health.

Dr. Ashish Singh, Anup Institute of Orthopaedics and Rehabilitation, G 75-77, PC Colony, Lohia Nagar, Kankarbagh, Patna, Bihar, India - 800020. E-mail: drashishsingh@hotmail.com

Introduction: Robotic-arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty (RA-TKA) has emerged as a promising intervention for degenerative osteoarthritis of the knees. Nevertheless, the accuracy of this intervention is inadequately studied. This study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of bone resections in the distal femur and proximal tibia during total knee arthroplasty (TKA) performed with Stryker’s MAKO® robotic arm interactive orthopedic system.

Materials and Methods: This single-center, prospective observational cohort study focused on patients with end-stage degenerative knee osteoarthritis who underwent RA-TKA performed by a single surgeon from September 2023 to March 2024. The bone resection accuracy was verified in two steps: In vivo verification using Stryker’s planar probe and in vitro manual verification using digital vernier calipers.

Results: Among 55 patients included in the study, 63.6% were males. The mean age of the patients was 59.15 ± 8.31 years (Range: 42–78). Primary osteoarthritis accounted for 92.7% of cases, while secondary osteoarthritis constituted 7.3%. The mean absolute difference for medial and lateral tibial cuts was 0.29 (0.45) mm and 0.38 (0.53) mm, respectively, and medial and lateral distal femoral cuts was 0.16 (0.19) mm and 0.41 (0.51) mm, respectively. Of the total 55 bone resections, 52 (95%) had an accuracy of <1 mm.

Conclusion: The Stryker MAKO® robotic system demonstrated high-level precision in bone resections, with accuracy levels exceeding those reported in the literature for conventional jig-based TKA. Preserving bone stock is crucial for revision surgeries and long-term joint health. These findings validate the system's technical reliability and support the continued integration of robotic technology in knee arthroplasty.

Keywords: Bone resection, implantation, mechanical alignment, robotic-arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty.

In recent decades, total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has emerged as one of the most successful surgical interventions for patients suffering from degenerative osteoarthritis of the knee joint [1]. This procedure offers significant improvements in quality of life by providing patients with a pain-free and stable knee joint, thereby enhancing mobility and overall function [2]. The global rise in TKA procedures is attributed to advancements in surgical techniques, improved patient outcomes, and the growing demand for joint replacement surgeries, driven by an aging population and increasing obesity rates [3]. The evolution of TKA techniques has seen a progression from conventional approaches to more advanced methods, such as patient-specific implants, computer-assisted navigation, and robotic-arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty (RA-TKA) [4,5]. These advancements aim to address the challenges associated with conventional techniques, such as variability in surgical outcomes and the need for greater precision in implant positioning and alignment. However, amid these technological advancements, there remains a debate regarding the primary objective of TKA techniques. Some advocate for achieving neutral mechanical alignment within a narrow range of variation (typically within ± 3°), emphasizing the importance of optimizing implant position for long-term durability and implant survivorship [6,7,8]. Others argue for prioritizing the attainment of balanced flexion and extension gaps, regardless of mechanical alignment, to promote more natural knee kinematics and improve functional outcomes for patients [9,10,11]. RATKA, such as procedures using the MAKO® Robotic Arm Interactive Orthopedic System (RIO; MAKO Stryker Corporation, Fort Lauderdale, Florida), has significantly enhanced the accuracy of bone resections, offering potential advantages for achieving these objectives compared to conventional techniques [5]. Despite these advancements, very few studies in the literature have specifically verified the accuracy of bone resections in RA-TKA, particularly in the distal femur and proximal tibia. To address this gap, this study aimed to evaluate the accuracy of bone resections in the distal femur and proximal tibia during total RA-TKA performed with the MAKO® robotic system.

Study design, setting, and patient criteria

This was a single-center prospective observational study that was conducted between September 2023 and March 2024. The study included patients with end-stage knee osteoarthritis (both primary and secondary) who underwent RA-TKA using the MAKO RIO robotic platform. All the surgeries were done by a single surgeon (A.S., second author) with over 10 years of experience in the field of robotic joint replacement surgery. Patients who did not consent to be a part of the study were excluded from the study.

Study procedure

All patients who were included in the study underwent a pre-operative computed tomography (CT) scan of the knee as per the robotic protocol, that is, with 3D reconstruction and a slice thickness of 0.5 mm[12]. Segmentation was done by a trained MAKO® product specialist, who subsequently generated the pre-operative plan with a primary focus on implant sizing and placement. Following segmentation and CT landmarking, the next step involved adding resection landmarks. These landmarks functioned as digital jigs, enabling precise bone resections to be performed subsequently. These digital guides were placed on the proudest points of the bone. Tibial resection landmarks were placed on the posterior one-third of the medial and lateral aspects of the tibial plateau; and for the distal femur, the landmarks were placed on the most proud and prominent point. During surgery, the patient’s actual anatomy was matched with the virtual anatomy created from the pre-operative CT-based plan. Following this, ligament balancing and bone resections were performed. Once all the bone resections were completed using the robotic arm, a thorough wash with pulsatile lavage was conducted to remove any bony debris.

Verification of the accuracy of bone cuts

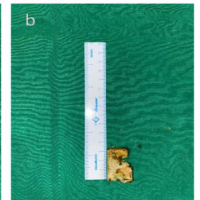

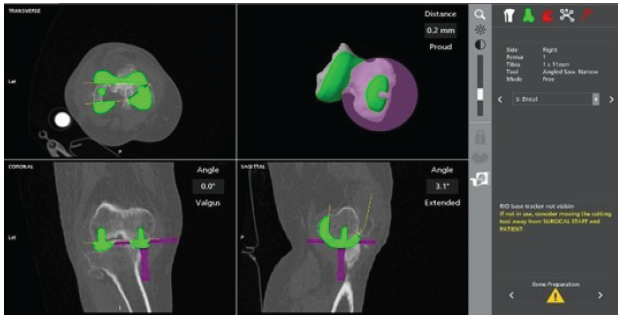

The verification of cut accuracy was carried out in two steps: In vivo verification of the depth of bone resection via Stryker MAKO’s planar probe (Fig. 1 and 2), which indicates whether the cuts are proud or deep relative to the planned resection depth.

Figure 1: In vivo verification of bone resection accuracy using the MAKO robotic system’s planar probe.

Figure 2: Robotic software screen showing in vivo verification of bone resection accuracy done using the MAKO robotic system’s planar probe.

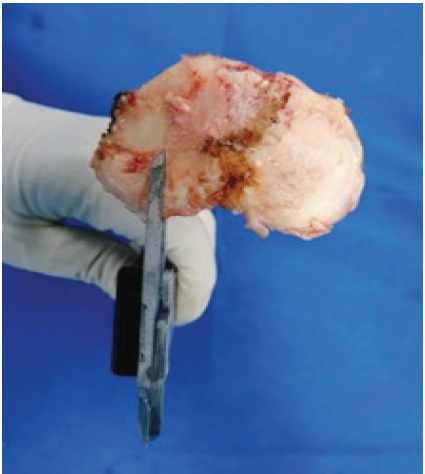

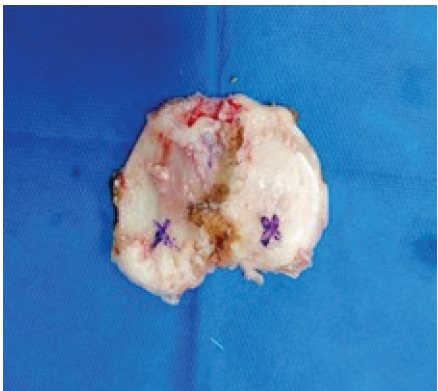

Manual in vitro verification of the bone cuts (Fig. 3) was performed after the resections, following the methodology outlined by Seidenstein et al., [5]. A digital vernier caliper was used to measure the depth of the cuts, which was then compared with the pre-operative plan for accuracy. The jaws of the vernier caliper were kept exactly at the resection landmarks placed during the pre-operative planning (posterior one-third of the medial and lateral aspects of the tibial plateau and the proudest point of the distal femur) (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 3: Manual verification of bone cuts (tibia and femur) using a digital vernier caliper. TM: Tibia medial, TL: Tibia lateral, DM: Distal femur medial, DL: Distal femur lateral.

Figure 4: The jaws of the vernier caliper are being positioned at the approximate locations of the resection landmarks identified during segmentation and planning.

Figure 5: Approximate position where the resection landmarks were marked during segmentation and planning.

Ethical considerations

Before conducting the study, ethical approval was obtained from the institutional ethics committee. All participants gave informed written consent to use their anonymized data for research purposes. All procedures performed in this study were in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki.

Statistical analysis

All data obtained during the study were analyzed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 20 (IBM Corp., Armonk, NY). Qualitative variables were summarized as frequencies and percentages. Quantitative normally distributed variables were summarized as mean, standard deviation (SD), minimum, and maximum.

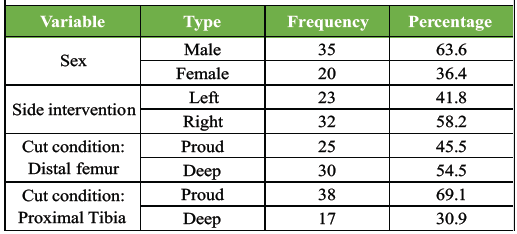

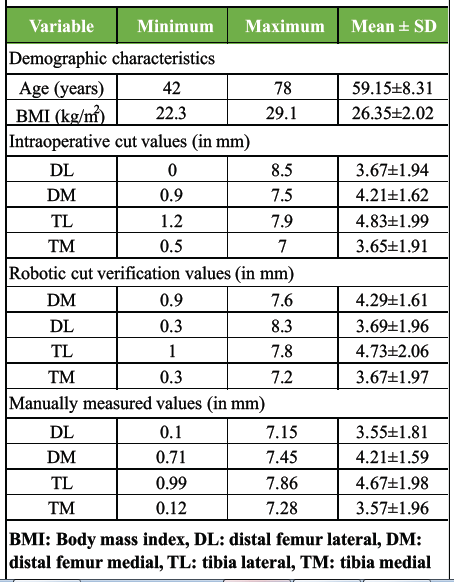

During the study period, a total of 55 patients underwent RA-TKA. Of the 55 patients, males constituted approximately two-thirds of the sample (63.6%) (Table 1). The mean age of the patients was 59.15 ± 8.31 years, with a range of 42 to 78 years (Table 2). The mean body mass index was 26.35 ± 2.02 kg/m2 (22.3–29.1) (Table 2).

Table 1: Frequency distribution of patients’ characteristics (n=55)

Table 2: Summary of descriptive statistics (n=55)

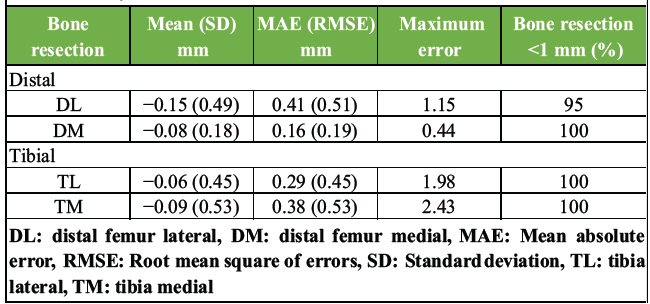

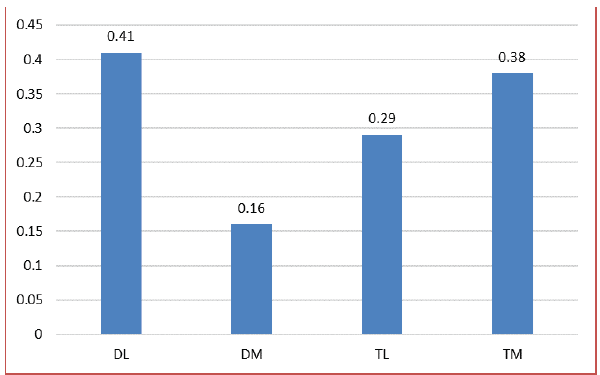

Of the 55 patients diagnosed with end-stage degenerative osteoarthritis, 51 (92.7%) had primary knee osteoarthritis, and 4 (7.3%) had secondary knee osteoarthritis. Thirty-two patients (58.2%) underwent surgery on the right side, while 23 patients (41.8%) underwent surgery on the left side. For the distal femur, the cuts were proud in 45.5% of cases and deep in 54.5% of cases. For the tibia, proud cuts constituted 69.1% of cases, while deep cuts accounted for 30.9% of cases (Table 1). With regard to cut measurements, the mean cut size of the lateral aspect of the was 3.55 ± 1.81 mm for manual measurement, 3.67 ± 1.94 mm for intraoperative measurement, and 3.69 ± 1.96 mm for robotic measurement (Table 2). For the medial aspect of the distal femur (DM, distal femur medial), the mean cut size was 4.21 ± 1.59 mm for manual measurement, 4.21 ± 1.62 mm for intraoperative measurement, and 4.29 ± 1.61 mm for robotic measurement. For the tibia, the mean cut size was 4.67 ± 1.98 mm (TL, tibia lateral), 4.83 ± 1.99 mm (intraoperative), and 4.73 ± 2.06 mm (robotic measurement); for the medial aspect (TM, tibia medial), the values were 3.57 ± 1.96 mm (manual), 4.29 ± 1.61 mm (intraoperative), and 3.67 ± 1.97 mm (robotic) (Table 2). Table 3 depicts the mean absolute difference, mean absolute error (MAE), root mean square of errors (RMSE), maximum error, and bone resections <1 mm for the cuts across different regions. For the distal femur, the MAE (RMSE) was 0.41 (0.51) mm for DL and 0.16 (0.19) mm for DM (Fig. 6). For the tibia, the MAE (RMSE) was 0.29 (0.45) mm for TL and 0.38 (0.53) mm for TM (Fig. 6). 95% of distal femoral bone resections and 100% of proximal tibial bone resections were within 1 mm of the pre-operative plan (Table 3).

Table 3: Study outcomes

Figure 6: A bar chart demonstrating the mean absolute error (in millimeters) of the bone cuts at different regions. DL: distal femur lateral, DM: distal femur medial, TL: tibia lateral, TM: tibia medial.

TKA is a cornerstone of orthopedic surgery, providing significant relief and restoring function for patients with advanced knee osteoarthritis [1,2]. In our study, we evaluated the efficacy of the MAKO Robotic Arm Interactive Orthopedic system, exploring its role in facilitating precise bone resections. One of the primary advantages of RA-TKA is its ability to enhance pre-operative planning and assessment [13]. The MAKO system allows surgeons to analyze the native anatomy of the knee joint, including the size and shape of the bones, as well as the depth of resection required [14]. This pre-operative assessment enables surgeons to develop a comprehensive surgical plan tailored to the individual patient’s anatomy, thereby optimizing implant selection and placement [14]. In our experience with RA-TKA using the MAKO robotic system, we were able to precisely position the polyethylene component according to the pre-operative plan in 95% of cases. This is remarkable as it preserves more native bone stock, which could be invaluable in the event of revision surgery [15]. Preserving bone stock is essential for enabling future interventions, such as revision surgeries, and for maintaining long-term joint health [16]. In addition, the precision offered by the MAKO system allows fine bone cuts, surpassing what is achievable with conventional jig-based TKA procedures [16]. While conventional methods struggle to achieve cuts of 2 mm or less, RA-TKA enables cuts as precise as 0.5 mm if necessary [4,16]. This capability not only conserves significant bone stock but also permits tailored resections to meet the specific requirements of individual patients [4,16]. The findings of our study also revealed a high degree of accuracy in achieving planned bone resections with the MAKO system. We observed that 95% of distal femoral bone resections and 100% of proximal tibial bone resections were lying within 1 mm of the pre-operative plan.

Our findings align with those reported by Li et al., in their 2022 prospective cohort study involving 36 patients who underwent robotic RA-TKA [17]. They reported an MAE from the plan for the DL and DM femoral cuts ranging from 0.39 mm (0.62) to 0.65 (0.81) mm, and a RMSE from the plan for the TL and TM ranging from 0.48 (0.16) to 0.56 (0.75) mm. Similar to our results, they observed that 91.7% of the bone resections were within ≤1 mm of the pre-operative plan. Similar accuracy values were reported by Zhang et al., [18] in their meta-analysis of 16 studies comparing RA-TKA and manual TKA. This study involved a single surgeon experienced in robotic surgery; consequently, we acknowledge that surgeons in the early stages of their learning curve may encounter different results. Factors, such as operative time, soft-tissue balance, haptic boundary management, and pin placement may vary with experience. Nevertheless, our findings demonstrate that a high level of resection accuracy is consistently achievable once technical proficiency is reached, highlighting the system’s potential for surgical standardization. Despite the promising results observed in our study, several limitations must be acknowledged. First, the sample size was relatively small, consisting of only 55 knees. While our findings demonstrate high precision in a controlled environment, future multi-center trials involving multiple surgeons with varying levels of experience are necessary to confirm these results. Larger cohorts are needed to validate our findings and enhance the generalizability of the results. This study was designed as a technical validation; consequently, it did not assess soft tissue balance, implant positioning, or long-term patient-reported outcomes. In addition, the lack of a comparative cohort, such as conventional or other robotic-assisted TKA systems, limits the ability to draw definitive conclusions regarding relative clinical efficacy. The future research should aim to evaluate the performance of different robotic platforms to provide a comprehensive understanding of their relative advantages and limitations. Furthermore, our study primarily focused on the technical aspects of surgery, such as the accuracy of bone resections, without assessing patient-reported outcomes or satisfaction. While achieving precise bone resections is essential for optimal implant placement and mechanical alignment, the ultimate goal of TKA is to improve patients’ quality of life and functional outcomes. Future research should incorporate patient-reported outcome measures to evaluate the impact of RA-TKA on post-operative pain relief, functional improvement, and overall satisfaction.

Based on the results of this study, the use of the MAKO platform for RA-TKA demonstrated a high degree of accuracy and predictability in bone resection and alignment. The precision offered by the MAKO system allows excellent accuracy and fine bone cuts, presenting a significant improvement over the error margins typically reported in literature for conventional jig-based TKA procedures. Preservation of bone stock is crucial for facilitating revision surgeries and maintaining long-term joint health. These results support the application of this technology in establishing RA-TKA as a standard of care in the management of end-stage osteoarthritis of the knee.

Mako Robotic-assisted total knee arthroplasty offers a high level of precision, allowing consistent execution of the surgical plan and optimal bone stock preservation, establishing a reliable technical standard for surgeons performing total knee arthroplasty.

References

- 1. Steinhaus ME, Christ AB, Cross MB. Total knee arthroplasty for knee osteoarthritis: Support for a foregone conclusion? HSS J 2017;13:207-10. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Canovas F, Dagneaux L. Quality of life after total knee arthroplasty. Orthop Traumatol Surg Res 2018;104:S41-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Kurtz SM, Lau E, Ong K, Zhao K, Kelly M, Bozic KJ. Future young patient demand for primary and revision joint replacement: National projections from 2010 to 2030. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2606-12. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Batailler C, Swan J, Sappey Marinier E, Servien E, Lustig S. New technologies in knee arthroplasty: Current concepts. J Clin Med 2020;10:47. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Seidenstein A, Birmingham M, Foran J, Ogden S. Better accuracy and reproducibility of a new robotically-assisted system for total knee arthroplasty compared to conventional instrumentation: A cadaveric study. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2021;29:859-66. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Chaudhary C, Kothari U, Shah S, Pancholi D. Functional and clinical outcomes of total knee arthroplasty: A prospective study. Cureus 2024;16:e52415. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Manjunath KS, Gopalakrishna KG, Vineeth G. Evaluation of alignment in total knee arthroplasty: A prospective study. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2015;25:895-903. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Begum FA, Kayani B, Magan AA, Chang JS, Haddad FS. Current concepts in total knee arthroplasty : Mechanical, kinematic, anatomical, and functional alignment. Bone Jt Open 2021;2:397-404. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Lee GC, Wakelin E, Plaskos C. What is the alignment and balance of a total knee arthroplasty performed using a calipered kinematic alignment technique? J Arthroplasty 2022;37:S176-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Nisar S, Palan J, Rivière C, Emerton M, Pandit H. Kinematic alignment in total knee arthroplasty. EFORT Open Rev 2020;5:380-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Karasavvidis T, Pagan Moldenhauer CA, Lustig S, Vigdorchik JM, Hirschmann MT. Definitions and consequences of current alignment techniques and phenotypes in total knee arthroplasty (TKA) – there is no winner yet. J Exp Orthop 2023;10:120. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Stojadinović M, Mašulović D, Kadija M, Milovanović D, Milić N, Marković K, et al. Optimization of the “Perth CT” protocol for preoperative planning and postoperative evaluation in total knee arthroplasty. Medicina (Mex) 2024;60:98. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Grau L, Lingamfelter M, Ponzio D, Post Z, Ong A, Le D, et al. Robotic arm assisted total knee arthroplasty workflow optimization, operative times and learning curve. Arthroplasty Today 2019;5:465-70. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Schafer P, Mehaidli A, Zekaj M, Padela MT, Rizvi SA, Chen C, et al. Assessing knee anatomy using Makoplasty software a case series of 99 knees. J Orthop 2020;20:347-51. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. MacAskill M, Blickenstaff B, Caughran A, Bullock M. Revision total knee arthroplasty using robotic arm technology. Arthroplast Today 2022;13:35-42. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Anderl C, Steinmair M, Hochreiter J. Bone preservation in total hip arthroplasty. J Arthroplasty 2022;37:1118-23. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Li C, Zhang Z, Wang G, Rong C, Zhu W, Lu X, et al. Accuracies of bone resection, implant position, and limb alignment in robotic-arm-assisted total knee arthroplasty: A prospective single-centre study. J Orthop Surg Res 2022;17:61. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Zhang J, Ndou WS, Ng N, Gaston P, Simpson PM, Macpherson GJ, et al. Robotic-arm assisted total knee arthroplasty is associated with improved accuracy and patient reported outcomes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Knee Surg Sports Traumatol Arthrosc 2022;30:2677-95. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]