Endoscopic FHL tenotomy can effectively correct post-traumatic Checkrein deformity of the great toe and also associated clawing of other toes, emphasizing the functional strength of the anatomical connection at the Knot of Henry and allowing for a single, minimally invasive intervention.

Dr. Banoth Valya, Department of Orthopaedics, Gandhi Medical College and Hospital, Secunderabad, Telangana, India. E-mail: orthovalya@gmail.com

Introduction: Checkrein deformity is a dynamic flexion deformity of the great toe, most often occurring after distal tibial trauma due to flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tethering or contracture. This report presents a rare case of post-traumatic checkrein deformity managed successfully with endoscopic FHL tenotomy.

Case Report: A 16-year-old male presented with dynamic hallux flexion deformity, 3 years after internal fixation for a distal tibia and fibula fracture. Clinical examination confirmed checkrein deformity. Endoscopic FHL tenotomy was performed via hindfoot endoscopy. Postoperatively, the deformity resolved, and the patient achieved full function with no recurrence at 6 months.

Conclusion: Endoscopic FHL tenotomy is a safe, effective, and minimally invasive technique for treating checkrein deformity, even in delayed presentations.

Keywords: Checkrein deformity, flexor hallucis longus, endoscopic tenotomy, hindfoot arthroscopy, tibial fracture.

Checkrein deformity is a rare but functionally significant dynamic deformity of the hallux characterized by a flexion contracture of the interphalangeal joint and extension contracture of the metatarsophalangeal joint, which is most apparent during ankle dorsiflexion and is totally or partially corrected with plantarflexion of the ankle. This phenomenon of clawing of toes following a tibial fracture was first described by Clawson in 1974 [1]. The word “Checkrein” originates from equestrian terminology, which is a strap used to prevent a horse from lower its head. Analogously, in this deformity, the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) acts as a physical “rein,” restraining the great toe from extending as the ankle dorsiflexes. This phenomenon is believed to result from tethering, fibrosis, or ischemic contracture of the FHL muscle or tendon, typically following lower limb trauma. It has been associated with distal tibial or ankle fractures, [2,3] as well as with talar and calcaneal fractures. In these cases, it is believed to be due to entrapment of the FHL between the callus [4] or scar tissue [5] at the fracture site. It can also occur as a consequence of fibrotic contracture following a compartment syndrome of the deep posterior compartment [6]. In cases of tibial fractures, especially when managed surgically or with prolonged immobilization, the FHL tendon can become tethered at the fracture site or within the interosseous membrane, restricting its normal excursion. This leads to the checkrein deformity. There is an anatomical interdependence between the FHL and flexor digitorum longus (FDL) tendons known as the Chiasma plantare or knot of Henry, which is a fibrous junction located in the midfoot region that allows load sharing and coordinated toe flexion. In the setting of FHL contracture or tethering, force transmission through these slips may cause simultaneous deformity of the second (and occasionally third) toes [7,8]. This explains the multi-toe involvement in some cases of checkrein deformity. Thus, the multifactorial etiology of checkrein deformity involves not only post-traumatic or ischemic changes in the FHL but also highlights the anatomical interdependence between FHL and FDL tendons. The deformity can be subtle in early stages but may progress to limit dorsiflexion of the ankle, impair gait, and interfere with normal footwear use. Diagnosis is primarily clinical, supported by dynamic examination of toes during passive ankle motion [9]. Conservative treatments, including physiotherapy and splinting, have limited success in established cases. Surgical intervention is typically required, most commonly in the form of FHL tendon Z-lengthening or tenotomy. Open procedures, while effective, may be associated with significant soft-tissue dissection, longer recovery periods, and risk of wound complications [10]. In recent years, endoscopic techniques have emerged as a minimally invasive alternative, offering direct visualization, reduced soft-tissue trauma, lower risk of neurovascular injury, and faster rehabilitation [11]. This case report presents a patient with post-traumatic checkrein deformity, which was successfully treated using endoscopic FHL tenotomy, underscoring the utility of this modern approach.

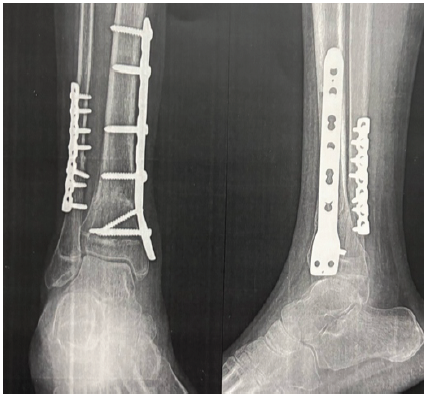

A 16-year-old male presented with complaints of persistent deformity of the right great toe and other toes, associated with discomfort during walking and difficulty wearing closed footwear. He had allegedly sustained a closed distal tibia and fibula fracture 3 years prior, which was managed with open reduction and internal fixation. The patient noticed the onset of great toe deformity approximately 3 weeks postoperatively, with increasing severity over time. Despite conservative measures, including physiotherapy, the deformity persisted and began to interfere with daily activities. On clinical examination, there was a visible dynamic flexion deformity of the right great toe that accentuated with active or passive dorsiflexion of the ankle and resolved on plantarflexion. The other toes also had dynamic flexion. The limb was neurovascularly intact. Radiographs of the leg and foot showed well-healed fractures with intact implants (Fig. 1 and 2).

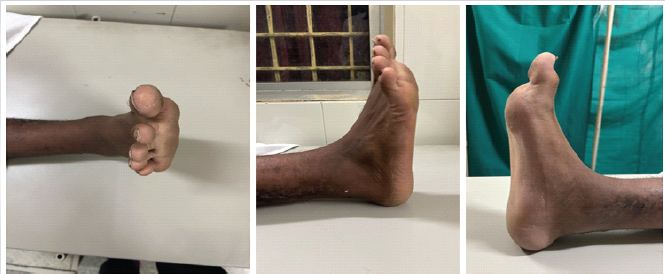

Figure 1: Preo-perative image showing checkrein deformity of the toes.

Figure 2: Pre-operative X-ray.

Given the clinical and imaging findings, a diagnosis of post-traumatic checkrein deformity of the hallux was made. The patient was counselled and subsequently taken up for endoscopic FHL tenotomy.

Surgical technique

The patient was positioned in the prone position under spinal anesthesia with a pneumatic tourniquet applied to the thigh. Standard sterile aseptic precautions were taken.

A standard two-portal hindfoot endoscopy was performed using posteromedial and posterolateral portals (Fig. 3).

Figure 3: Image showing surface markings of portals on either side of the Achilles tendon.

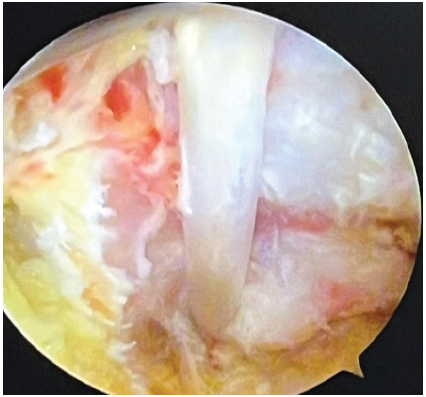

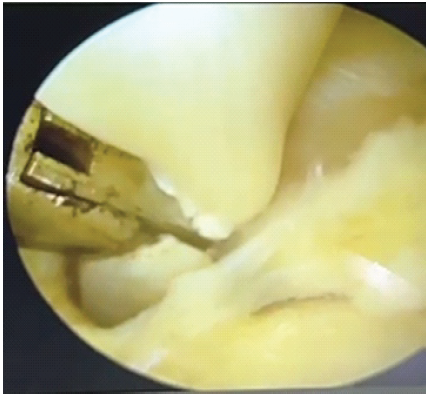

A 4.0-mm 30° arthroscope was introduced through the posterolateral portal. The FHL tendon was visualized at the level of the posterior ankle, just posterior to the talus. Dynamic testing by flexion of the great toe was performed to confirm the tightness and tethering of the FHL tendon during passive dorsiflexion of the ankle (Figs. 4 and 5).

Figure 4: Identification of the flexor hallucis longus tendon.

Figure 5: endoscopic tenotomy of the flexor hallucis longus tendon.

The FHL tendon sheath was carefully released using a shaver and radiofrequency device. A partial tenotomy of the FHL tendon was performed at the zone of entrapment. Intraoperatively, correction of the deformity was confirmed by passive ankle movement. The portals were closed with nylon sutures.

The previous hardware was removed after placing the patient in the supine position. A sterile dressing and below-knee posterior slab were applied with the ankle in neutral position (Figs. 6 and 7).

Figure 6: Image taken on the 1st post-operative day showing correction of Checkrein deformity.

Figure 7: Clinical image at 6-week follow-up.

Post-operative course

Postoperatively, the patient was mobilized on the 1st day. Passive and active ankle and toe range-of-motion exercises were initiated immediately. At follow-up after 3 months, the patient demonstrated full ankle range of motion without recurrence of toe deformity. The great toe remained in a neutral position during gait, and the patient reported complete resolution of symptoms.

Checkrein deformity is a relatively uncommon but functionally significant complication following distal tibial trauma. Although its pathophysiology can be multifactorial, mechanical adhesion of the FHL tendon is the most common cause. In our case, the deformity became clinically evident within 3 weeks following internal fixation for a distal tibia and fibula fracture, suggesting early entrapment or adhesion of the FHL at the fracture or surgical site. The anatomical relationship between the FHL and the FDL tendons, especially at the knot of Henry, further complicates the deformity. Tendinous interconnections in this region can lead to the involvement of adjacent toes, most commonly the second digit, due to force transmission across shared slips of tendons. Our patient demonstrated dynamic flexion of other toes, supporting the theory of anatomical interdependence between the tendons. Traditional surgical treatments have included open FHL tenolysis, Z-lengthening, or muscle-tendon release, which, although effective, are associated with greater soft-tissue dissection, risk of neurovascular injury, and prolonged recovery, In contrast, hindfoot endoscopic release of the FHL tendon offers a minimally invasive alternative that allows direct visualization, targeted tenolysis, and faster post-operative rehabilitation with fewer complications. Lui first described endoscopic FHL tenotomy for hallux rigidus and checkrein deformity [12]. In our case, the patient underwent endoscopic FHL tenotomy through a standard two-portal hindfoot approach, which allowed safe access to the fibro-osseous tunnel and successful release of the tethered tendon. Postoperatively, the deformity resolved completely, and the patient regained full, pain-free function without recurrence at 3 months. The delayed presentation in our patient, 3 years post-trauma, highlights the importance of early recognition and referral for appropriate surgical management.

Endoscopic FHL tenotomy performed through hindfoot endoscopy is a minimally invasive and effective technique for the management of post-traumatic checkrein deformity, even in cases with delayed presentation. In the present case, correction of both the great toe and second toe deformities was achieved solely through FHL tenotomy, without direct intervention on the FDL tendon. This simultaneous resolution highlights the anatomical and functional integrity of the confluence between FHL and FDL at the knot of Henry. Knowledge about this interconnection allows for a more focused surgical approach, reducing operative morbidity while ensuring satisfactory functional outcomes.

In cases of post-traumatic checkrein deformity, especially when involving multiple toes, surgeons should consider the confluence of FHL and FDL at the knot of Henry. Endoscopic FHL tenotomy offers a safe and effective treatment option that can address deformities of both the great toe and adjacent toes without the need for additional tendon procedures.

References

- 1. [1] Clawson DK. Claw toes following tibial fracture. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1974;103:47-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. [2] Wehbé MA, Dalal RB. Checkrein deformity of the hallux and its surgical management. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2001;83:688-90. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. [3] Abdel-Ghani H, Farouk O. Checkrein deformity of the great toe after closed tibial shaft fractures. J Orthop Trauma 2008;22:188-91 [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. [4] Carr JB. Complications of calcaneus fractures entrapment of the flexor hallucis longus: Report of two cases. J Orthop Trauma 1990;4:166-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. [5] Boszczyk A, Zakrzewski P, Pomianowski S. Hallux Checkrein deformity resulting from the scarring of long flexor muscle belly-case report. Ortop Traumatol Rehabil 2015;17:71-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. [6] Hernandez-Cortes P, Pajares-Lopez M, Hernandez-Hernandez MA. Ischemic contracture of deep posterior compartment of the leg following isolated ankle fracture. J Am Podiatr Med Assoc 2008;98:404-407. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. [7] Beggs LA, Steinbach LS. MR imaging of the tarsal tunnel and related spaces. Magn Reson Imaging Clin N Am 2001;9:567-82. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. [8] Carroll MJ, Hunter LY. The relationship of the flexor hallucis longus and flexor digitorum longus muscles to digital deformity. Foot Ankle 1985;5:144-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. [9] Christoforakis J, Kokkinakis M, Di Mascio L. The Checkrein deformity of the hallux: Diagnosis and treatment. Foot Ankle Surg 2005;11:49-52. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. [10] Rudge WB, Roukis TS. Flexor hallucis longus tendon transfer: A review. Clin Podiatr Med Surg 2009;26:561-81. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. [11] Martinkevich P, Rahbek O, Viberg B. Endoscopic flexor hallucis longus tenotomy in patients with Checkrein deformity: A case series. Foot Ankle Surg 2019;25:214-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12.