Clinico-radiologically predetermined patient-specific multisite steroid injection combined with structured physiotherapy provides rapid pain relief and significant functional improvement in primary frozen shoulder.

Dr. Prince Shanavas Khan, Department of Orthopaedics, Apollo Adlux Hospital, Kochi, Kerala, India. E-mail: drpskhan@gmail.com

Background: Frozen shoulder (FS) is characterized by pain and progressive restriction of motion, with treatment aimed at pain relief, functional improvement, and shortening disease duration. While conservative management is preferred, the best non-surgical modality remains unclear due to heterogeneity in the literature. The current study is to determine the efficacy of patient-specific multi-site landmark-based steroid injection in combination with a standardized physiotherapy protocol followed at our center in the management of FSs.

Methods: In this prospective study, 94 patients with primary FS, confirmed via ultrasound and X-ray, received intra-articular and multisite betamethasone injections (8 mg diluted in 8 mL of 2% lignocaine). A total of 5 mL was injected intra-articularly, while the remaining was divided among the areas of tenderness and inflammation pre-determined clinically or radiologically by ultrasound. Injections were performed by a single shoulder surgeon, followed by an 8-week physiotherapy protocol. Patients were assessed at 2, 4, 8- and 12-weeks using range of motion (ROM), Visual Analog Scale (VAS), American Shoulder and Elbow Scoring system (ASES), and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index scores.

Results: Statistically significant improvements were observed: mean abduction increased from 124° to 173° (P = 0.001), forward flexion from 123° to 174° (P = 0.040), and external rotation from 26° to 55° (P = 0.009). The mean ASES score improved from 28.8 to 92.5 (P = 0.001), VAS decreased from 6.7 to 0.4, and internal rotation improved by 4 vertebral levels.

Conclusion: The results of our study demonstrate that patient-specific multi-site steroid infiltration significantly reduces pain and improves ROM and clinical outcomes in FS patients.

Keywords: Frozen shoulder, betamethasone, anterior approach, intra-articular steroid injection, adhesive capsulitis.

Frozen shoulder (FS), also known as adhesive capsulitis, is a common pathological condition of the shoulder joint characterized by pain and progressive restriction of both active and passive range of motion (ROM) [1]. The Upper Extremity Committee of ISAKOS defines FS as idiopathic shoulder stiffness, distinguishing it from secondary shoulder stiffness, which has an identifiable underlying cause [2]. The condition affects approximately 2–5% of the general population and is most prevalent in individuals aged 40–60 years [3]. Although considered idiopathic, FS has a strong association with metabolic disorders, particularly diabetes mellitus (DM) and hypothyroidism, with diabetics being 2–4 times more likely to develop the condition [4]. Neviaser described FS as a condition progressing through distinct clinical phases, beginning with a painful freezing phase, followed by a frozen phase characterized by marked stiffness, and finally a thawing phase during which gradual improvement in motion occurs [5]. Historically, FS was regarded as a self-limiting condition with eventual full recovery. However, emerging evidence suggests that a significant proportion of patients may continue to experience persistent pain, limited ROM, and functional impairment even after the so-called thawing phase, highlighting the need for timely and effective intervention [6,7]. Conservative management remains the first-line treatment for FS. Commonly employed non-surgical modalities include oral non-steroidal anti-inflammatory drugs, oral corticosteroids, intra-articular steroid injections, hydrodilatation, and physiotherapy, either alone or in combination [8]. Oral nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory Drugs are frequently prescribed for pain relief but have not demonstrated consistent functional improvement. Oral corticosteroids have shown short-term benefits in pain reduction and ROM; however, these effects are often transient and accompanied by concerns regarding systemic side effects, particularly in patients with diabetes and prediabetes [9,10]. While intra-articular steroid injections are widely accepted as an effective treatment modality, there remains considerable variability in clinical practice regarding the type of steroid used, dosage, injection technique, number of injections, and choice of injection site. Most published studies have focused on single-site intra-articular injections, typically targeting the glenohumeral joint, despite evidence suggesting that FS involves inflammation of multiple periarticular structures such as the subacromial bursa, rotator interval, coracohumeral ligament, and biceps tendon sheath [11]. The role of hydrodilatation in FS management also remains controversial. Although proposed to improve capsular distension and ROM, systematic reviews and randomized controlled trials have demonstrated inconsistent results, with several studies reporting no additional functional benefit when compared to intra-articular steroid injection alone [12,13,14]. Moreover, hydrodilatation is associated with potential adverse effects such as increased pain and, rarely, capsular rupture. Surgical interventions, including manipulation under anesthesia (MUA) and arthroscopic capsular release, are generally reserved for refractory cases. Although arthroscopic capsular release has demonstrated good outcomes, it carries inherent risks such as nerve injury, recurrence of stiffness, and iatrogenic instability [15,16]. Similarly, MUA has been associated with complications including capsular tears, labral injury, hemarthrosis, and fractures, with randomized studies failing to show clear superiority over supervised exercise programs [17]. Given these concerns, there is a continued need to optimize non-surgical treatment strategies that are effective, safe, and reproducible. Furthermore, despite the availability of ultrasound-guided injection techniques, evidence has not consistently demonstrated a clinically significant advantage over landmark-based injections, while increasing cost and procedural time. Importantly, there is limited literature evaluating patient-specific, multisite steroid injection strategies that target clinically and radiologically identified pain generators in FS. Given the multifactorial involvement of periarticular structures in FS and the limitations of existing treatment protocols, we sought to evaluate a clinico-radiologically predetermined, landmark-based, patient-specific multisite steroid injection approach. By targeting the glenohumeral joint along with other inflamed periarticular structures identified clinically and by ultrasound, we aimed to address multiple pain generators in a single sitting. The purpose of this prospective study was to assess the clinical and functional outcomes of this multisite steroid injection protocol combined with a standardized physiotherapy regimen. We hypothesized that this comprehensive, patient-specific approach would result in faster pain relief, improved ROM, and superior functional recovery compared to conventional single-site injection strategies, while avoiding the risks associated with hydrodilatation and surgical intervention.

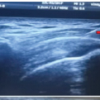

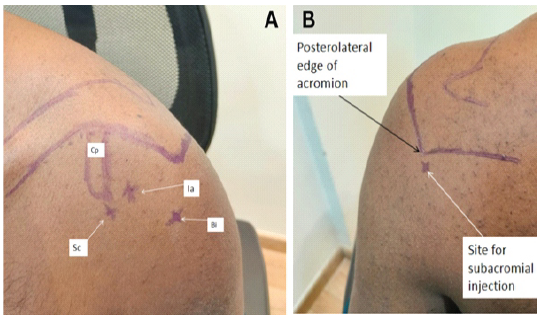

We identified patients in the shoulder clinic presenting with symptoms directing to a FS and constructed a prospective case series. Patients were clinically examined by the fellowship-trained shoulder surgeon on their presentation at a single shoulder clinic. A detailed history was taken, followed by a clinical examination highlighting the identification of areas of tenderness over the subacromial space, subdeltoid space, intra-articular joint space, and over the biceps tendon, as well as assessing ROM. All patients then underwent plain radiographs as well as an ultrasound study to rule out secondary causes of shoulder pain and stiffness and to identify co-existing pathologies, which could be a contraindication to steroid injection (e.g., Rotator cuff tears). In cases where ultrasound scans suggested findings other than those attributable to a FS, an magnetic resonance imaging was requested. Consecutive patients satisfying the definition of FS by The Upper Extremity Committee of ISAKOS were enlisted for the study. 94 such patients were recruited between January 2020 and September 2023. Diabetics were required to achieve optimal glycemic control (Target of fasting blood sugar <110 mg/dl for at least 7 consecutive days) before receiving the steroid injections. After obtaining informed consent, under sterile precautions, patient-specific multisite steroid injections were performed in a single sitting in the glenohumeral joint and areas of clinical tenderness as well as in bursae having sonographic evidence of inflammation (Fig. 1a).

Figure 1: Surface marking for shoulder injection (a) Anterior subcoracoid, intraarticular, biceps injections, and coracoid process (b) Posterior view.

The steroid injection consisted of 8 mg of betamethasone (4 mg/mL) mixed with 6 mL of plain 2% lignocaine. 5 mL of the solution was injected into the glenohumeral joint by an anterior-based approach. The rest of the solution was injected into the other areas of tenderness/inflammation determined as above. The glenohumeral injection was given using the anterior approach with the site of injection being 1 cm lateral to coracoid, medial to the humeral head and angled slightly superior and lateral (Fig. 2b). Patients with subacromial inflammation were infiltrated inferior to the posterolateral corner of the acromion with the direction slightly lateral, toward the anterolateral corner and the needle advanced by 2–3 cm (Figs. 1 and 2a).

Figure 2: (a) Site for subacromial injection (b) Site for intraarticular injection (c) Site for subcoracoid injection (d) Site for biceps injection.

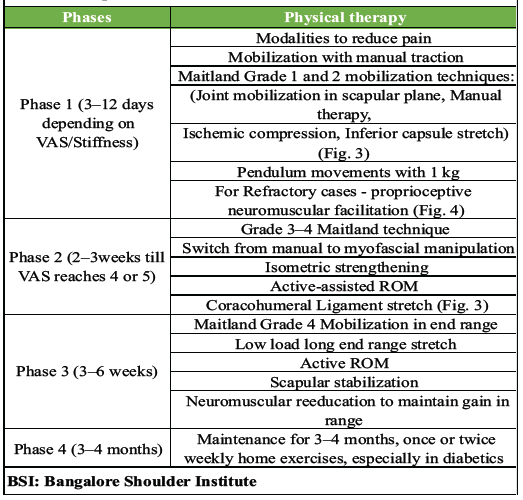

Sub-coracoid steroid injection was done by direct palpation of the tip of the coracoid process followed by infiltration laterally and inferiorly (Fig. 2c). The biceps tendon however was not directly infiltrated, and the injection was given around the tendon by palpation of the lips of the bicipital groove in the anteromedial aspect of the proximal arm corresponding to the area of tenderness (Fig. 2d). Following the injection, the shoulder joint was immobilized for 24 h. Patients were re-examined after 48 h to rule out complications such as infection and neurovascular deficits, following which physiotherapy was initiated. The physiotherapy protocol that we utilize is a comprehensive, structured, evidence-based amalgamation of recognized techniques, which we have termed “Bangalore Shoulder Institute (BSI) Frozen Shoulder Protocol” (BSI Frozen Shoulder Protocol,” as summarized in Table 1 (Fig 3, 4).

Figure 3: (a) Low load, long duration inferior capsular stretch. (b) Inferior capsular stretch (c) Coracohumeral ligament stretch.

Figure 4: Proprioceptive neuromuscular facilitation with deep breathing.

Inclusion criteria

Patients were aged – 18–77 years and satisfied the definition of FS by The Upper Extremity Committee of ISAKOS. Other causes of limitation of ROM were ruled out clinically and confirmed with radiological means.

Exclusion criteria

Patients with arthritic changes, calcific deposits, and rotator cuff tears were excluded based on radiological findings. Patients symptomatic in the contralateral shoulder were excluded. Patients with previous shoulder surgery were excluded from the study. Ethical consideration: This study has been approved by the Institutional Ethics Committee of BANGALORE SHOULDER INSTITUTE, BANGALORE (IEC No: 006/12/23, Approval Date: Dec 17, 2023). The study was conducted in accordance with the ethical standards of the Declaration of Helsinki. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants before enrollment. Based on previous studies evaluating functional outcomes following steroid injection in FS, a minimum clinically important difference of 10 points in the American Shoulder and Elbow Scoring system (ASES) score was considered significant. Assuming a standard deviation of 20, with a power of 80% and an alpha error of 0.05, the minimum required sample size was calculated to be 82 patients. Accounting for potential loss to follow-up, a total of 94 patients were recruited for the study. Outcome measurements: ROM and the scores (pre-injection and 2, 4, 8, 12 weeks were measured by one clinical researcher who was blinded to the current study, and the ROM was measured with a goniometer. The initial evaluation included the recording of a detailed medical history and clinical examination of the shoulder joint (Active and Passive ROM, tenderness in specific bursae around the joint). A Visual Analog Scale (VAS) scoring system determined pain, and the ASES scoring and Shoulder Pain and Disability Index (SPADI) scoring systems were utilized to evaluate subjective function at each point in the study. Shoulder ROM was measured with the patient seated. Internal rotation at the back was measured by the vertebral level reached with the tip of the thumb.

Physical therapy: (BSI Protocol)

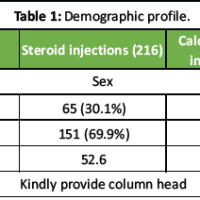

The physiotherapy protocol is explained in Table 1.

Table 1: BSI protocol

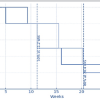

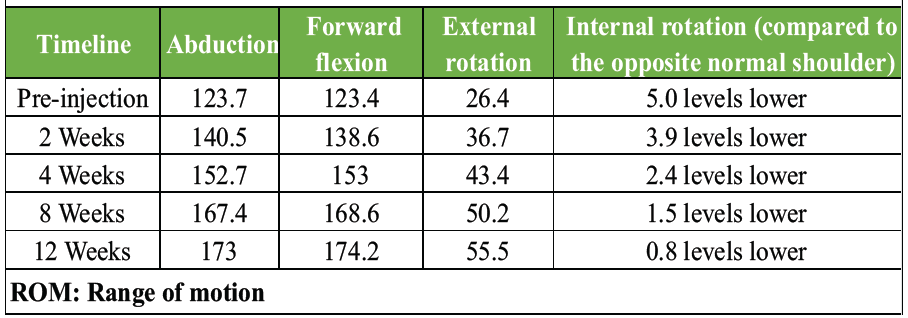

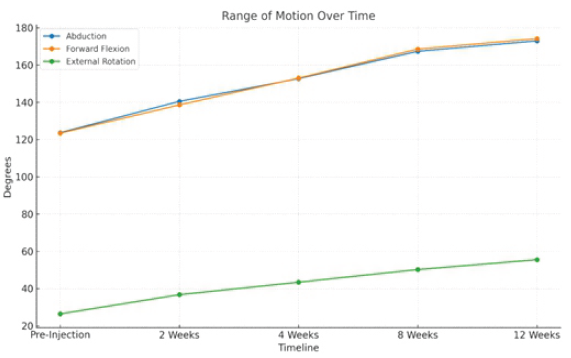

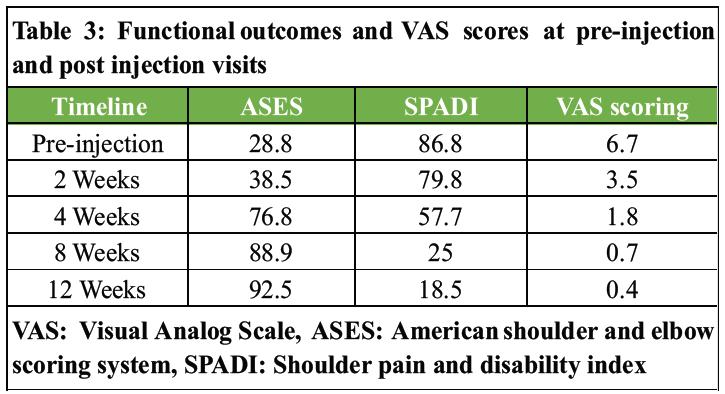

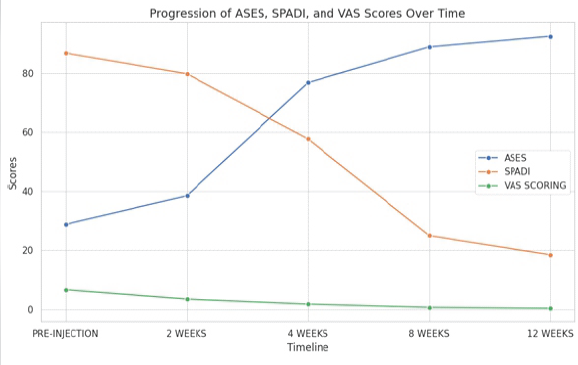

The sample size consisted of 94 patients diagnosed with primary adhesive capsulitis, and data were collected from February 2020 to September 2023. The study population consisted of 36 men (38%) and 58 women (62%), who were at a mean age of 52.6 ± 10.7 years (range 18–77 years). The mean duration of symptoms was 5.1 months ± 2.5 months (range 1–12 months). 25 (26%) patients reported a history of DM. 9 (10%) patients reported a history of hypothyroidism. The female population was higher by 70%. We also noted in our study that in 53 cases, the left shoulder was affected, while the right shoulder was affected in the remaining 41 cases. Out of the 94 patients, 51 patients had subacromial tenderness (54%), 31 patients had subcoracoid tenderness (33%), and 29 patients had tenderness around the biceps tendon (31%). Table 2 and Graph 1 depict the results of ROM pre-injection and at 2, 4, 8, and 12 weeks post-injection. Similarly, the functional outcomes and VAS scores are shown in Table 3 and Graph 2. Abduction, forward flexion, and external rotation are all displayed in degrees (Graph 1).

Table 2: Results of ROM at pre-injection and post-injection visits

Graph 1: Results of range of motion at pre-injection and post-injection visits.

Table 3: Functional outcomes and VAS scores at pre-injection and post injection visits

Graph 2: Functional outcomes and Visual Analog Scale scores at pre-injection and post-injection visits.

Statistical analysis

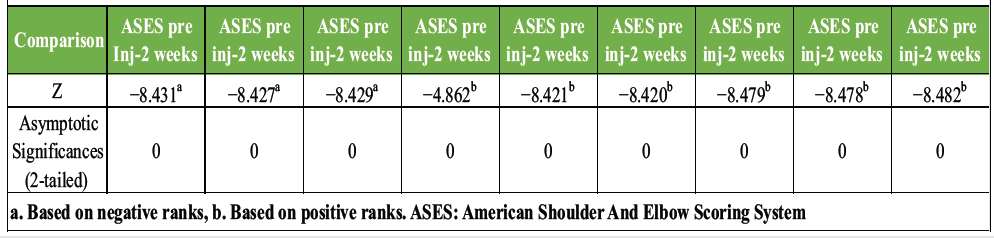

The differences in ROM, VAS, and functional outcomes between pre-injection status and during post-injection visits were assessed using the paired samples test, while the statistical significance of these differences was evaluated by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test (Table 4).

Table 4: Analysis of data by the Wilcoxon signed-rank test

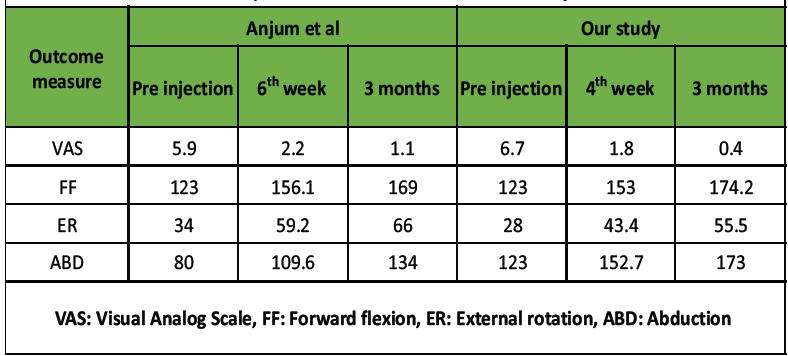

In this prospective study, we observed significant early and sustained improvements in pain, ROM, and functional outcomes following clinico-radiologically predetermined, landmark-based, patient-specific multisite steroid injection combined with a structured physiotherapy protocol in patients with primary FS. Meaningful reductions in VAS scores and improvements in ASES, SPADI, and shoulder ROM were evident as early as 2 weeks post-intervention and continued to improve over the 12-week follow-up period. The treatment modality employed in the present study differs fundamentally from the routine intra-articular steroid injection commonly used in the management of FS. Conventional practice typically involves a single-site intra-articular injection targeting the glenohumeral joint, based on the assumption that the pathology is confined to capsular inflammation. However, FS is increasingly recognized as a condition involving inflammation of multiple periarticular structures, including the subacromial bursa, rotator interval, coracohumeral ligament, and the biceps tendon sheath. Our approach utilizes a patient-specific multisite steroid injection strategy guided by focused clinical examination and ultrasound findings, targeting both intra-articular and extra-articular pain generators in a single sitting. By addressing multiple sources of inflammation simultaneously, this technique aims to achieve more comprehensive pain relief, facilitate earlier participation in physiotherapy, and promote faster functional recovery compared to routine single-site intra-articular steroid injections. In the quest for the ideal treatment for FS, different steroids, injection sites, techniques, and frequency of injection have been studied. As reported by the Consensus Survey of Shoulder Specialists, conservative management remains the most popular as the first line of treatment, and 63% of participants agreed that steroids have a beneficial role [1]. However, despite the abundance of therapeutic modalities, there remains a paucity of guidelines regarding the treatment ladder in the management of FS. There is no definitive guideline as to when to change from one treatment modality to another. However, it is generally acceptable to wait for 3 months before declaring any conservative treatment ineffective [18]. The choice of betamethasone for our study is supported by its high potency (more than 6 times that of triamcinolone) and long half-life of 8.5 days [19]. Furthermore, its solubility reduces its propensity to crystallize, a process which has been incriminated in post-steroid flare reactions [20]. With regards to the injection technique, our decision to opt for the anterior approach is supported by Deng et al., who reported that a decrease in VAS was consistently better at each follow-up and the improvements in functional scores and external rotation were faster and more significant when using the anterior approach rather than a posterior approach for intra articular steroid injection in FS [21]. Another area of variability in practice is the use of ultrasound-guided (US-guided) versus landmark-based steroid injections. While the accuracy of US-guided injections is higher (90% versus 76.2%), this difference was not found to be statistically significant in a cohort study of 41 patients by Raeissadat et al. Improvements in pain, functional scores, and ROM (except for extension), albeit more in the US-Guided group, failed to reach statistical significance [22]. The lack of significant clinical benefit of US-guided compared to landmark-based steroid injections was echoed by a Cochrane study, which concluded that there was no advantage in terms of pain, function, shoulder ROM, or safety in using the former technique [23]. Rather more evident was the fact that US-guided injections would be more costly and time-consuming [22]. We have strived to base our practice on the best available evidence and robust scientific reasoning, but the ultimate litmus test remained our results. The mean VAS score decreased from a pre-injection value of 6.7–0.7. This improvement was significantly greater than that achieved by Song et al., who treated their patients with US-guided triamcinolone injections and reported a mean VAS score reduction from 5.6 to 3.0 [24]. Interestingly, this reduction occurred over a mean of 2.1 months, whereas our results demonstrate a comparable VAS of 3.5 at a mere 2 weeks and a VAS of 1.8 at 4 weeks only. Anjum et al., [25] evaluated the efficacy of a single intra-articular injection of methylprednisolone combined with physiotherapy and physiotherapy alone. The authors concluded that the results were significantly better in the combination group. The mean VAS score in the combination group decreased to 1.1 from 5.9 at 3 months. The VAS score had reached 2.2 by 6 weeks post-injection. The mean SPADI score improved from 62.5 to 33.0 at 6 weeks and 18.9 at 3 months in his patients, compared to 86.8 at pre-injection to 18.5 at 3 months in our study. They also reported a mean increase in internal rotation by 7 levels by 6 weeks and 9 levels by 3 months compared to an improvement of 4 levels by 3 months (Table 5). An explanation for this discrepancy could be the fact that their patients overall had a more significantly reduced internal rotation than our patients – the mean internal rotation was S3, whereas the most severely restricted internal rotation was S1 in our study group.

Table 5: Comparison of our results with those of Anjum et al

The results of our prospective case series demonstrate that clinico-radiologically predetermined landmark-based multisite steroid infiltration using betamethasone leads to a remarkable reduction in pain as well as significant improvement in ROM and function in the treatment of the FS.

Patient-specific multisite landmark-based steroid injection targeting clinically and radiologically identified pain generators, when combined with structured physiotherapy, is an effective, safe, and reproducible non-surgical treatment option for primary frozen shoulder, leading to rapid pain relief and significant functional recovery.

References

- 1. Cho CH, Lee YH, Kim DH, Lim YJ, Baek CS, Kim DH. Definition, diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis of frozen shoulder: A consensus survey of shoulder specialists. Clin Orthop Surg 2020;12:60-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 2. Itoi E, Arce G, Bain GI, Diercks RL, Guttmann D, Imhoff AB, et al. Shoulder stiffness: Current concepts and concerns. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2016;32:1402-14. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 3. Green HD, Jones A, Evans JP, Wood AR, Beaumont RN, Tyrrell J, et al. A genome-wide association study identifies 5 loci associated with frozen shoulder and implicates diabetes as a causal risk factor. PLoS Genet 2021;17:e1009577. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 4. Pandey V, Aier S, Agarwal S, Sandhu AS, Murali SD. Prevalence of prediabetes in patients with idiopathic frozen shoulder: A prospective study. JSES Int 2023;8:85-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 5. Neviaser TJ. Adhesive capsulitis. Orthop Clin North Am 1987;18:439-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 6. Wong CK, Levine WN, Deo K, Kesting RS, Mercer EA, Schram GA, et al. Natural history of frozen shoulder: Fact or fiction? A systematic review. Physiotherapy 2017;103:40-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 7. Favejee MM, Huisstede BM, Koes BW. Frozen shoulder: The effectiveness of conservative and surgical interventions–systematic review. Br J Sports Med 2011;45:49-56. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 8. Guyver PM, Bruce DJ, Rees JL. Frozen shoulder – A stiff problem that requires a flexible approach. Maturitas 2014;78:11-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 9. Powell C, Chang C, Naguwa SM, Cheema G, Gershwin ME. Steroid induced osteonecrosis: An analysis of steroid dosing risk. Autoimmun Rev 2010;9:721-43. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 10. Lorbach O, Anagnostakos K, Scherf C, Seil R, Kohn D, Pape D. Nonoperative management of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: Oral cortisone application versus intra-articular cortisone injections. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2010;19:172-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 11. Koraman E, Turkmen I, Uygur E, Poyanlı O. A Multisite injection is more effective than a single glenohumeral injection of corticosteroid in the treatment of primary frozen shoulder: A randomized controlled trial. Arthrosc J Arthrosc Relat Surg 2021;37:2031-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 12. Carette S, Moffet H, Tardif J, Bessette L, Morin F, Frémont P, et al. Intraarticular corticosteroids, supervised physiotherapy, or a combination of the two in the treatment of adhesive capsulitis of the shoulder: A placebo-controlled trial. Arthritis Rheum 2003;48:829-38. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 13. Saltychev M, Laimi K, Virolainen P, Fredericson M. Effectiveness of hydrodilatation in adhesive capsulitis of shoulder: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Scand J Surg 2018;107:285-93. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 14. Paruthikunnan SM, Shastry PN, Kadavigere R, Pandey V, Karegowda LH. Intra-articular steroid for adhesive capsulitis: Does hydrodilatation give any additional benefit? A randomized control trial. Skeletal Radiol 2020;49:795-803. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 15. Cutbush K, Italia K, Narasimhan R, Gupta A. Frozen shoulder 360° release. Arthrosc Tech 2021;10:e963-7. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 16. Kivimäki J, Pohjolainen T, Malmivaara A, Kannisto M, Guillaume J, Seitsalo S, et al. Manipulation under anesthesia with home exercises versus home exercises alone in the treatment of frozen shoulder: A randomized, controlled trial with 125 patients. J Shoulder Elbow Surg 2007;16:722-6. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 17. Patel R, Urits I, Wolf J, Murthy A, Cornett EM, Jones MR, et al. A Comprehensive update of adhesive capsulitis and minimally invasive treatment options. Psychopharmacol Bull 2020;50(4 Suppl 1):91-107. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 18. Mukherjee RN, Pandey RM, Nag HL, Mittal R. Frozen shoulder – A prospective randomized clinical trial. World J Orthop 2017;8:394-9. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 19. Shah A, Mak D, Davies AM, James SL, Botchu R. Musculoskeletal corticosteroid administration: Current concepts. Can Assoc Radiol J 2019;70:29-36. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 20. Fawi HM, Hossain M, Matthews TJ. The incidence of flare reaction and short-term outcome following steroid injection in the shoulder. Shoulder Elbow 2017;9:188-94. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 21. Deng Z, Li Z, Li X, Chen Z, Shen C, Sun X, et al. Comparison of outcomes of two different corticosteroid injection approaches for primary frozen shoulder: A randomized controlled study. J Rehabil Med 2023;55:jrm00361. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 22. Raeissadat SA, Rayegani SM, Langroudi TF, Khoiniha M. Comparing the accuracy and efficacy of ultrasound-guided versus blind injections of steroid in the glenohumeral joint in patients with shoulder adhesive capsulitis. Clin Rheumatol 2017;36:933-40. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 23. Zadro J, Rischin A, Johnston RV, Buchbinder R. Image-guided glucocorticoid injection versus injection without image guidance for shoulder pain. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2021;8:CD009147. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 24. Song A, Katz JN, Higgins LD, Newman J, Gomoll A, Jain NB. Outcomes of ultrasound-guided glen humeral corticosteroid injections in adhesive capsulitis. Br J Med Res 2014;5:570-8. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- 25. Anjum R, Aggarwal J, Gautam R, Pathak S, Sharma A. Evaluating the outcome of two different regimes in adhesive capsulitis: A prospective clinical study. Med Princ Pract 2020;29:225-30. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]