[box type=”bio”] Learning Point for the Article: [/box]

Pelvic osteomyelitis should be part of a differential diagnosis with children presenting with groin and thigh pain and must be managed with appropriate MDT

Case Report | Volume 8 | Issue 4 | JOCR July – August 2018 | Page 86-88| Saurabh Deore, Mohit Bansal. DOI: 10.13107/jocr.2250-0685.1174

Authors: Saurabh Deore[1], Mohit Bansal[2]

[1]Department of Medicine,Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, Norwich, United Kingdom.

[2]Department of Orthopaedics,Guy’s Hospital, London, United Kingdom.

Address of Correspondence:

Dr. Saurabh Deore,

Norwich Medical School, University of East Anglia, STA103 Suffolk Terrace,Norwich, NR47TJ, United Kingdom.

E-mail: sdsaurabhdeore@gmail.com

Abstract

Introduction: Pelvic osteomyelitis presents a diagnostic challenge due to its rarity and non-specific presentation. Early advance imaging in the form of magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) is warranted if clinical suspicion is high. We present an unusual case of pubic rami osteomyelitis, presenting with clinical findings of septic arthritis treated appropriately with early imaging and intravenous antibiotics with satisfactory outcome.

Case Report: A 9-year-old boy presented to accident and emergency with 2 days history of the left-sided groin and thigh pain, inability to weight bear, and feeling generally unwell following a rugby match. There was no history of trauma or recent infection. On examination, the child had fever, limp on weight-bearing, tender groin, and signs of an irritable hip. Laboratory report showed raised inflammatory markers and blood culture showed Staphylococcus aureus. Presumptive diagnosis of septic hip joint was made as there was effusion on ultrasound examination. Specialist opinion was sought and MRI confirmed changes of the left pubic rami osteomyelitis. The child was treated with intravenous antibiotics, with excellent clinical response after 48 h.

Conclusion: Pelvic osteomyelitis in a child is a rare occurrence. This case highlights the significance of having a wide differential diagnosis for non-specific hip pain in a child. An MRI will help with the diagnosis if there is any uncertainty of the underlying cause. Early treatment with IV antibiotics is ideal for uncomplicated recovery. A multidisciplinary team approach is of utmost importance.

Keywords: Pelvic, osteomyelitis, Staphylococcus aureus.

Introduction

Pelvic osteomyelitis is an uncommon cause of osteomyelitis in children [1,2]. The presenting symptoms of pelvis osteomyelitis overlap with the presentation of other disease processes such as irritable hip, septic arthritis, acute abdomen, or discitis making it hard to clinically diagnose it [3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10]. This makes clinical diagnosis difficult for the clinician who leads to misdiagnosis and inappropriate treatment. Conventional imaging fails to diagnose the condition and early magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) aids in diagnosis [4,11]. We present a case of the left pubic rami osteomyelitis caused by Staphylococcusaureus, presenting with clinical findings of septic arthritis treated appropriately with early imaging and intravenous antibiotics with satisfactory outcome.

Case Report

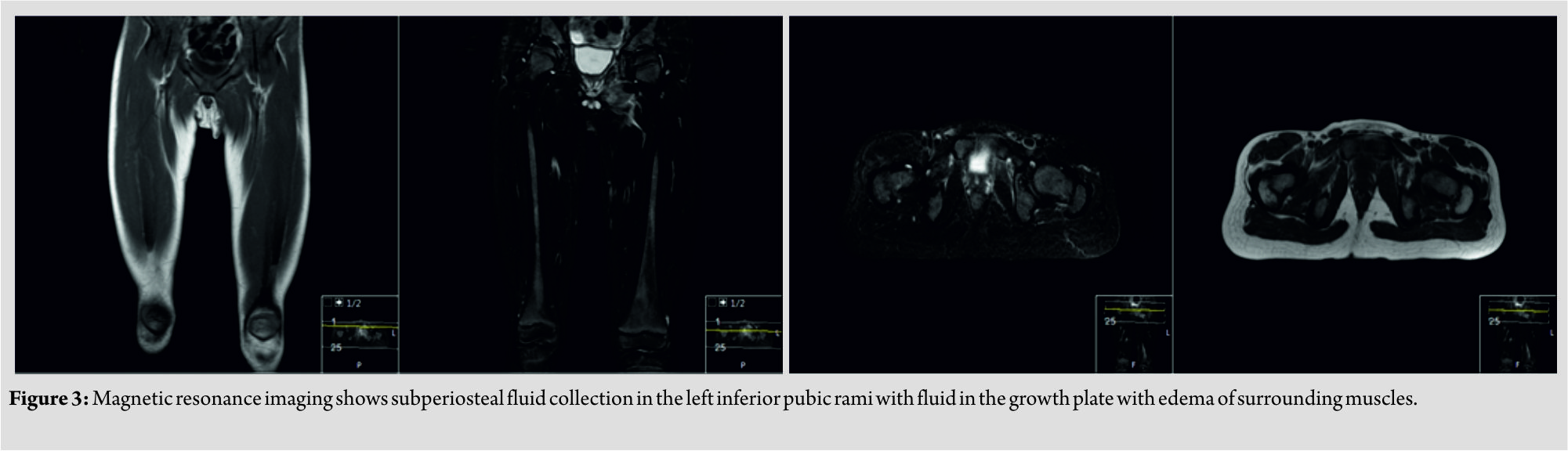

A fit and well 9-year-old boy presented to accident and emergency with 2 days history of the left-sided groin and thigh pain, inability to weight bear, and feeling generally unwell following a rugby match. There was no history of trauma or recent infection. On examination, the child had fever (38.6°), limp on weight-bearing, tender groin, and signs of an irritable hip. Local temperature around the hip was normal with no erythema. Laboratory report showed high white cell count (16.5 × 109/L), high neutrophil count (14.3 × 109/L),and high C-reactive protein (CRP) (97 mg/L); other laboratory tests were normal. Blood cultures for aerobic and anaerobic bugs grew Gram-positive cocci, methicillin-sensitiveS. aureus. A pelvic and lumbar spine X-rays were normal (Fig. 1).  An ultrasound of the left hip showed free fluid in the pelvis and some effusion in the hip joint (Fig. 2). A presumptive diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip was made. Specialist opinion from the pediatric orthopedic surgeon was sought, and before proceeding for surgical washout of the hip joint, MRI without sedation was organized to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 3). It showed subperiosteal fluid collection in the left inferior pubic rami with fluid in the growth plate with edema around the iliopsoas and short external rotators. The child was started on intravenous flucloxacillin after discussion with microbiologist, with excellent clinical response after 48 h and improvement of the inflammatory markers. The child made full recovery without any complications.

An ultrasound of the left hip showed free fluid in the pelvis and some effusion in the hip joint (Fig. 2). A presumptive diagnosis of septic arthritis of the hip was made. Specialist opinion from the pediatric orthopedic surgeon was sought, and before proceeding for surgical washout of the hip joint, MRI without sedation was organized to confirm the diagnosis (Fig. 3). It showed subperiosteal fluid collection in the left inferior pubic rami with fluid in the growth plate with edema around the iliopsoas and short external rotators. The child was started on intravenous flucloxacillin after discussion with microbiologist, with excellent clinical response after 48 h and improvement of the inflammatory markers. The child made full recovery without any complications.

Discussion

The incidence of pelvic osteomyelitis varies from 6.3 to 20% among children affected with osteomyelitis [1, 2, 12]. In the pelvis, the sites affected include ilium, ischium, the pubis, and acetabulum, ilium being the most common 38% due to its larger area and abundant blood supply [13]. Children over the age of 7 years are most likely to be affected with trauma as a possible risk factor [2]. The diagnosis of pelvic acute hematogenous osteomyelitis (AHOM) is a challenge because of its rarity, and the non-specific presentation leads to misdiagnosis of septic arthritis and inappropriate treatment as reported in the literature [6, 7, 9, 10]. The symptoms can range from pain in the hip, thigh, abdomen, or lumbar back, and the patient might have restricted hip mobility with difficulty walking or weight-bearing. The child can also present with a fever and local signs of inflammation such as swelling and erythema. Staphylococcus aureus is the most common organism found on blood culture, as in this case, with other organisms such as salmonella, Streptococcus, Streptococcus pneumoniae, and Fusobacterium also being localized infrequently[2, 14, 15].The various parts of the pelvis being affected might explain the referred pain to the different areas in the body, thus expanding the differential diagnoses at the time of presentation [1, 5, 12]. Pelvic AHOM can be mistaken for septic arthritis of the hip, acute abdomen, nephrolithiasis, osteomyelitis of the proximal end of femur, discitis, and cancer[3, 4, 5]. Blood tests are likely to show raised inflammatory markers with a raised erythrocyte sedimentation rate, CRP, and white cell count. Blood cultures are not always positive, but negative culture does not exclude the diagnosis of an infection. In pelvic osteomyelitis, radiographs are typically normal, ultrasound might show deep soft tissue swelling, and computer tomography will show early signs; however, MRI is the gold standard investigation [4, 11]. If the clinical signs along with imaging findings from ultrasound do not confirm the suspected diagnosis (from the list of differential diagnoses),then an MRI or bone scintigraphy is warranted. MRI is a more sensitive (97%) and specific (94%) modality when compared to scintigraphy. This combined with the bone or abscess aspirate and blood culture will aid in specific antibiotic against the detected organism [4, 8]. The management of methicillin-sensitive S. aureus, as in our case, is flucloxacillin with or without fosfomycin. This must be administered intravenously for quickest mode of action followed by oral antibiotics, duration guided by the clinical response, and improvement of the inflammatory markers. The treatment would be recommended even if the blood cultures are negative but high clinical suspicion. Surgery can be considered if there is failure to respond to antibiotics or abscess formation. Early diagnosis and treatment of osteomyelitis is important to prevent complications such as chronic infection, avascular necrosis, and growth abnormalities. This case emphasizes the importance of specialist input and early imaging in the form of MRI to avoid misdiagnosis, inappropriate treatment, and avoid complications. It also highlights the importance of multidisciplinary team approach in managing these cases with involvement of pediatric orthopedic surgeon, pediatrician, radiologist, microbiologist, and physiotherapist to achieve satisfactory outcome.

Conclusion

This case report highlights the significance of early management of pelvic osteomyelitis. Clinicians must have a high degree of suspicion in patients with non-specific symptoms, and the diagnosis of pelvic osteomyelitis must be considered as a differential in patients presenting with hip pain. Prompt multidisciplinary team approach to the management of such cases avoids complications.

Clinical Message

Pelvic osteomyelitis in a child is an uncommon diagnosis which requires high index of suspicion as the symptoms are non-specific and require early specialist input to avoid complication. It also highlights the importance of multidisciplinary team approach in managing these cases for satisfactory outcome.

References

1. Klein JD, Leach KA. Pediatric pelvic osteomyelitis. Clin Pediatr (Phila) 2007;46:787-90.

2. Kumar J, Ramachandran M, Little D, Zenios M. Pelvic osteomyelitis in children. J PediatrOrthop B 2010;19:38-41.

3. Tolley M, Morris A, Williams N. Pelvic osteomyelitis: Three unusual cases with predominantly abdominal symptoms. J Paediatr Child Health 2017;53:614.

4. Song KS, Lee SW, Bae KC. Key role of magnetic resonance imaging in the diagnosis of infections around the hip and pelvic girdle mimicking septic arthritis of the hip in children. J PediatrOrthop B 2016;25:234-40.

5. Sun X, Lou Y, Wang X. The diagnosis of iliac bone destruction in children: 22 cases from two centres. Biomed Res Int 2016;2016:2131859.

6. Kocialkowski C, Ryan W, Davis N. Case report of iliac osteomyelitis in a child, presenting as septic arthritis of the hip. J Orthop Case Rep 2014;4:19-21.

7. Takemoto RC, Strongwater AM. Pelvic osteomyelitis mimicking septic hip arthritis: A case report. J PediatrOrthop B 2009;18:248-51.

8. Weber-Chrysochoou C, Corti N, Goetschel P, Altermatt S, Huisman TA, Berger C. Pelvic osteomyelitis: A diagnostic challenge in children. J Pediatr Surg 2007;42:553-7.

9. Al-Qahtani SM. Osteomyelitis of the pubic ramus misdiagnosed as septic arthritis of the hip. West Afr J Med 2004;23:267-9.

10. Weinberg JR, Berman L, Dootson G, Mitchell R. Pubic osteomyelitis presenting as irritable hip. Postgrad Med J 1987;63:301-2.

11. McPhee E, Eskander JP, Eskander MS, Mahan ST, Mortimer E. Imaging in pelvic osteomyelitis: Support for early magnetic resonance imaging. J PediatrOrthop2007;27:903-9.

12. Zvulunov A, Gal N, Segev Z. Acute hematogenous osteomyelitis of the pelvis in childhood: Diagnostic clues and pitfalls. PediatrEmerg Care 2003;19:29-31.

13. Díaz Ruiz J, del Blanco Gómez I, Barrio AB, Labarga BH, Arribas JM. Uncommon localization of osteomyelitis. An Pediatr (Barc) 2007;67:240-2.

14. Akhras N, Blackwood A. Pseudomonas pelvic osteomyelitis in a healthy child. Infect Dis Rep 2012;4:e1.

15. Canessa C, Trapani S, Campanacci D, Chiappini E, Maglione M, Resti M. Salmonella pelvic osteomyelitis in an immunocompetent child. BMJ Case Rep 2011;2011:pii: bcr0220113831.

|

|

| Dr. Saurabh Deore | Dr. Mohit Bansal |

| How to Cite This Article: Deore S, Bansal M. Pelvic Osteomyelitis in a Child – A Diagnostic Dilemma. Journal of Orthopaedic Case Reports 2018. Jul-Aug ; 8(4): 86-88. |

[Full Text HTML] [Full Text PDF] [XML]

[rate_this_page]

Dear Reader, We are very excited about New Features in JOCR. Please do let us know what you think by Clicking on the Sliding “Feedback Form” button on the <<< left of the page or sending a mail to us at editor.jocr@gmail.com