Pseudoaneurysm of brachial artery can be a delayed or late complication of supracondylar humerus fracture, knowledge of this entity and a high index of suspicion is required in the immediate and long-term follow-up of these injuries to prevent limb threatening complications.

Dr. Shrihari L Kulkarni

Department of Orthopaedics, SDM College of Medical Sciences and Hospital,

Shri Dharmasthala Manjunatheshwara University, Dharwad, Karnataka, India.

E-mail: shrihari1711@gmail.com

Introduction: Supracondylar humerus fractures are very common fractures in children. About 10–14% are associated with vascular complications. We report a rare case of pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery which was promptly detected in a well-perfused hand nearly 2 weeks after reduction and fixation.

Case Report: A 10-year-old girl with Type I open supracondylar fracture of the left humerus (Modified Gartland Type 2) presented 2 weeks post-fixation with pulsatile mass in the elbow. Imaging revealed a pseudoaneurysm of brachial artery which was managed by excision and reconstruction using great saphenous vein graft. The fracture united uneventfully and the child made a full return to pre-fracture level of activity.

Conclusion: The case highlights the occurrence of pseudoaneurysm of brachial artery, a rare complication seen few days or weeks after the injury, which coincides with the post-operative period in children managed by surgical fixation. This emphasizes the need for periodic monitoring of the neurovascular status of the children even after successful reduction and fixation.

Keywords: Supracondylar humerus fracture, vascular complication, pseudoaneurysm.

Supracondylar humerus (SCH) fractures are one of the most common childhood injuries requiring surgical management with a peak incidence between 5 and 6 years [1,2]. Vascular complications involving the brachial artery are observed in about 10–14% of children with SCH fractures [3].

Children with displaced or open fractures have a higher incidence of vascular injury than those with non-displaced or closed fractures [4]. The various mechanisms for vascular injury include arterial laceration by sharp fracture fragment or Kirschner wires, compression from direct impact, and avulsion injuries. Most of the vascular injuries occur due to a penetrating trauma causing an inside-out rent in the skin presenting as an open fracture or with severe anterior contusion of the soft tissues of the elbow. It is, therefore, seen that a pre-operative thorough neurovascular evaluation is important in all children with SCH fracture. Pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery has been described with blunt trauma as well as with penetrating injuries [5].

Pseudoaneurysms are also notorious for their delayed presentation, in some instances presenting many years after the injury. Although rare, they can cause severe disabilities such as median nerve compression and upper extremity and finger loss due to thromboembolic complications in the hands and fingers. The present case highlights the importance of prompt recognition of this entity by vigilant follow-up during the post-operative period to make an early diagnosis and initiate appropriate treatment.

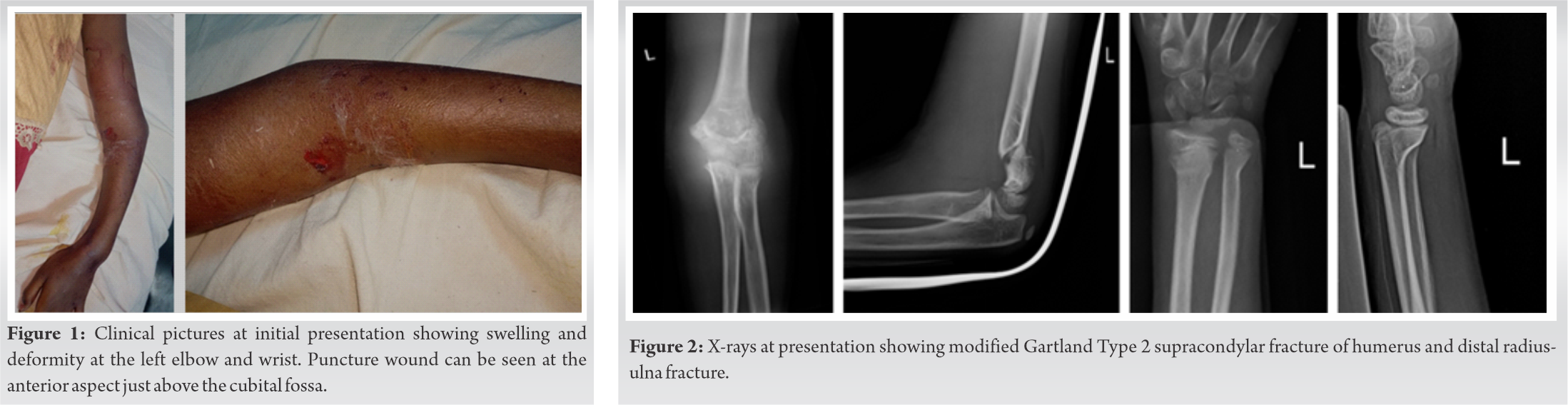

A 10-year-old girl presented to our emergency with pain, swelling, and inability to move her left elbow and wrist following a fall while playing. On examination, she had swelling around the elbow and wrist, with a puncture wound in the anterior aspect about 2 cm proximal to the cubital fossa with tenderness in the supracondylar region of humerus and distal end of radius, restricted, and painful movements at elbow and wrist (Fig. 1). Radiographs revealed a modified Gartland Type 2 SCH fracture with distal radius and ulna fracture (Fig. 2).

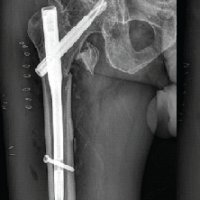

On a working diagnosis of Gustilo-Anderson Type-1 open [6] SCH fracture with distal radius and ulna fracture, the child was promptly taken up for wound irrigation, debridement, and closed pinning of the supracondylar fracture with two percutaneous K-wires from lateral condyle (Fig. 3).

The distal radius and ulna fractures were managed by closed reduction and pinning for radius and conservative treatment for ulna. Post-operative period was uneventful, and she was discharged with above elbow slab immobilization.

Two weeks later, the child returned for follow-up with a painful swelling over the front of the left elbow. A pulsatile mass was seen over the cubital fossa of the left elbow measuring around 3 cm × 2 cm swelling and inability to move (Fig. 4) with reduced volume of the radial pulse as compared to the opposite side. There were no distal neurological deficits in the upper limb. Capillary refill time was less than 3 s with normal turgor of the pulp and no skin discoloration.

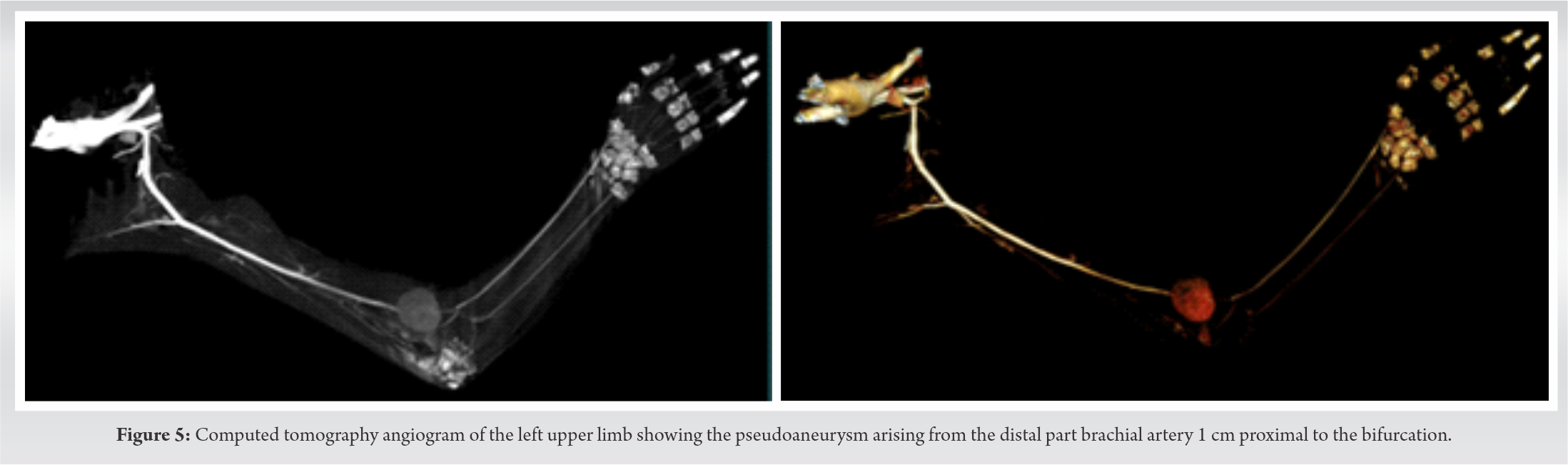

The patient was evaluated with color Doppler and computed tomography (CT) angiogram to confirm the location and size of the swelling. CT angiogram showed a well-defined saccular outpouching with smooth surface seen arising from the posteromedial wall of distal brachial artery, 1 cm proximal to its bifurcation suggestive of pseudoaneurysm of the left distal brachial artery. The aneurysmal sac was measured 3.5 × 1.9 cm with neck of 9–10 mm. There was no evidence of thrombus within the outpouching. The aneurysmal sac was located medial to brachial vessels with no obvious perianeurysmal leak was noted (Fig. 5).

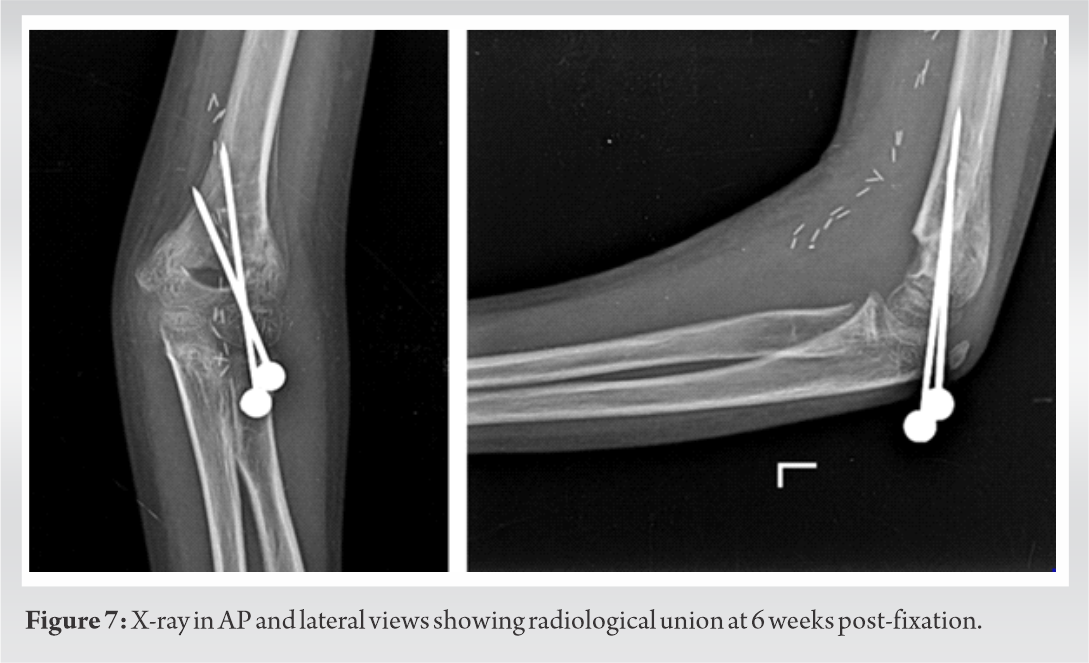

A plastic surgery consultation was obtained following which excision of the pseudoaneurysm was performed by the plastic surgery team. Intraoperatively, perivascular adhesions and inflammation were noted. There was no evidence of any K-wire tip protruding or piercing the artery. After excision, the arterial gap of 4.5 cm was reconstructed with a great saphenous vein graft (Fig. 6). The child made an uneventful recovery with the fracture uniting in 6 weeks and the child returning to pre-fracture level of activity by 3 months (Fig. 7).

SCH fractures are one of the most common fractures in childhood, especially in the first decade. They are broadly classified into extension type and flexion type depending on the direction of the displacement of the distal fragment. The extension type accounts for approximately 97–99% and is caused mainly by fall on the outstretched hand with hyperextension at the elbow [7].

The fractures are classified by modified Gartland classification of which Type III, Type IV, and open fractures are associated with a higher incidence of neurovascular complications [8]. Brachial artery injury is seen in around 10–14 % of SCH fractures. These patients majorly present with absent or feeble radial pulse while 10–20% can also present with pulseless (white) hand. Patients with pulseless hand and poor perfusion should undergo immediate exploration to rule out vascular injury. On the other hand, patients with pulselessness but having good perfusion can be managed with urgent closed reduction and internal fixation with K-wires followed by careful observation for any emerging signs of ischemia. In this regard, it is of absolute importance to differentiate between lack of pulse and poor perfusion of the extremity. Some of the clinical signs of poor perfusion of the extremity are loss of pulp turgor, increased capillary refill time more than 3 s, and discoloration of the fingers. Paresthesia may not be an accurate finding to suggest ischemia in a setting of a fracture. Majority of them will not require any further surgeries. There is still quite a lot of controversy surrounding the exact protocol for the management of children with pulseless limb with good perfusion in hand [3,9].

Pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery has been described with blunt trauma as well as with penetrating injuries. Intimal laceration by the fractured bony fragments is thought to be the most common mechanism in the pathogenesis. Other possible mechanisms include contusion or compression from direct impact and avulsion or traction injury from rotation [5]. In one of the studies, the pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery was attributed to the injury caused by the K-wires while fixation of the supracondylar fracture. In our case, an iatrogenic injury was unlikely as the K-wires had not pierced the anterior cortex anytime during the procedure. Studies have found significant correlation between the vascular injury and the involvement of the median nerve in SCH fractures. However, in our case, there were no neurological deficits [10].

Once diagnosed pseudoaneurysms should be managed with surgical excision and repair to overcome the risk of chronic ischemia associated with the conservative management. Delay in treatment can lead to the enlargement of the pseudoaneurysm which can further lead to hemorrhage, limb edema, cutaneous erosions, and compression of the adjacent neurological structures which can sometimes be the first symptom to appear. Primary surgical repair with interposition saphenous vein grafting (especially when arterial defect is more than 1 cm) is the most common operative technique in the management of the pseudoaneurysms. Recently, however, endovascular procedures have also been proposed [11,12]. In our case, the patient had an open fracture with a puncture wound, which was the main risk factor in the vascular complication. Unlike most children who are comfortable at 2 weeks post-fixation, our patient complained of pain and discomfort in the elbow which was concealed by the plaster. On opening the plaster, a pulsatile swelling of the elbow was detected with reduced volume of the radial pulse which alerted us to investigate further. Thus, a timely diagnosis and management could be done.

Pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery, though a rare complication of upper limb trauma, can lead to devastating complications. They are notorious for delayed presentation up to a year and in some cases for longer. The recognition of this entity is easy with prior history of upper limb trauma or surgery. In the immediate post-operative period, it is important to emphasize to the patients to return immediately if there is increasing pain or paresthesia in the limb concealed by the plaster. In such cases, after opening the plaster, a thorough clinical examination of the neurovascular status is mandatory to pick up such a rare but dangerous entity and initiate prompt treatment.

We would like to sincerely acknowledge the immense help provided by the plastic surgery team of our institution for prompt surgical excision of the pseudoaneurysm and arterial reconstruction.

There can be such delayed complications, hence, clinical examination is very important even in delayed post-operative period. Not only the presence or absence of pulse, even the rate and volume of pulse are important clinical signs to be focused on.

References

- 1.Dimeglio A. Growth in pediatric orthopaedics. In: Morrissy RT, Weinstein SL, editors. Lovell and Winters’s Pediatric Orthopaedics. 6th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Lippincott Williams & Wilkins; 2006. p. 35-65. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Cheng JC, Lam TP, Maffulli N. Epidemiological features of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in Chinese children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2001;10:63-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Luria S, Sucar A, Eylon S, Pinchas-Mizrachi R, Berlatzky Y, Anner H, Liebergall M, Porat S. Vascular complications of supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop B 2007;16:133-43. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Louahem DM, Nebunescu A, Canavese F, Dimeglio A. Neurovascular complications and severe displacement in supracondylar humerus fractures in children: Defensive or offensive strategy? J Pediatr Orthop B 2006;15:51-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Crawford DL, Yuschak JV, McCombs PR. Pseudoaneurysm of the brachial artery from blunt trauma. J Trauma 1997;42:327-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Kim PH, Leopold SS. In brief: Gustilo-Anderson classification. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2012;470:3270-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Mahan ST, May CD, Kocher MS. Operative management of displaced flexion supracondylar humerus fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2007;27:551-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Abzug JM, Herman MJ. Management of supracondylar humerus fractures in children: Current concepts. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2012;20:69-77. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.White L, Mehlman CT, Crawford AH. Perfused, pulseless, and puzzling: A systematic review of vascular injuries in paediatric supracondylar humerus fractures and results of a POSNA questionnaire. J Pediatr Orthop 2010;30:328-35. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Ergungor MF, Kars HZ, Yalin R. Median neuralgia caused by brachial pseudoaneurysm. Neurosurgery 1989;24:924-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Franz RW, Goodwin RB, Hartman JF, Wright ML. Management of upper extremity arterial injuries at an urban level 1 trauma centre. Ann Vasc Surg 2009;23:8-16. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Robbs JV, Naidoo KS. Nerve compression injuries due to traumatic false aneurysm. Ann Surg 1984;200:80-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]