Distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies without soft tissue procedure for severe hallux valgus can achieve an adequate correction.

Dr. Kenichiro Nakajima, Department of Orthopedic Surgery, Yashio Central General Hospital, Saitama, Japan. E-mail: nakajimakenichiro@hotmail.co.jp

Introduction: The commonly performed procedure for treating severe hallux valgus is proximal metatarsal osteotomy or first tarsometatarsal arthrodesis combined with a soft tissue procedure in which the severe intermetatarsal angle (IMA) is corrected using proximal metatarsal osteotomy or first tarsometatarsal arthrodesis; although a severe hallux valgus angle (HVA) can be corrected using the soft tissue procedure alone, the correction ability is low. Therefore, the more severe the hallux valgus is, the more difficult it is to correct.

Case Report: A 52-year-old woman (height, 142 cm; weight, 47 kg) with severe hallux valgus with an HVA of 80° and an IMA of 22° was treated with a combination of the distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies fixated using K-wires, which was a modification of Kramer’s and Akin’s procedures, without a soft tissue procedure. The concept behind this technique is that distal metatarsal osteotomy primarily corrects the hallux valgus, and when the correction is insufficient, the proximal phalanx osteotomy complements it, which ensures that the first ray is approximately straight. After 4.1 years of follow-up, the HVA and IMA were 16° and 13°, respectively.

Conclusion: Distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies without a soft tissue procedure were effective in treating a patient with severe hallux valgus with an HVA of 80°.

Keywords: Kramer’s procedure, Akin’s procedure, distal lateral soft tissue release, complication.

Severe hallux valgus is defined as having a hallux valgus angle (HVA) of >40° and an intermetatarsal angle (IMA) of >16° [1]. The commonly performed procedure for treating severe hallux valgus is proximal metatarsal osteotomy or first tarsometatarsal arthrodesis combined with a soft tissue procedure [1,2] in which the severe IMA is corrected using proximal metatarsal osteotomy or first tarsometatarsal arthrodesis; thus, correction ability of this procedure is high. In contrast, the severe HVA can be corrected using the soft tissue procedure alone, although the correction ability is low. Therefore, the more severe the hallux valgus is, the more difficult it is to correct. I have performed a combination of distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies fixated using K-wires without a soft tissue procedure for treating severe hallux valgus. In this case report, I present a case of severe hallux valgus with an 80° HVA.

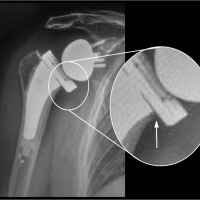

A 52-year-old woman with rheumatoid arthritis, Sjogren’s syndrome, and systemic lupus erythematosus presented to my clinic with severe hallux valgus and deformity of the second toe on the left foot. The patient’s height was 142 cm, and body weight was 47 kg (body mass index, 23.3 kg/m2). The roentgenograph demonstrated an 80° HVA and a 22° IMA. She underwent the surgical treatment described below.

Surgical Technique

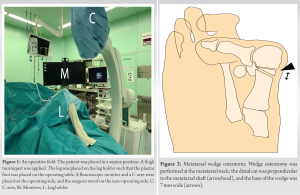

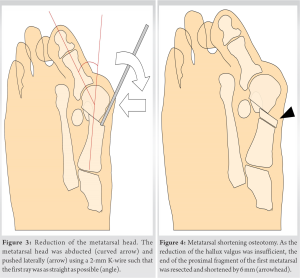

The patient was placed in the supine position, and a thigh tourniquet was applied to the left leg. The leg was placed on the leg holder such that the plantar foot was placed on the operating table. A fluoroscopic monitor and a C-arm were placed on the operating side, and the surgeon stood on the non-operating side (Fig. 1). The first metatarsal and proximal phalanx axes were marked with a surgical pen using fluoroscopic guidance. A 2-cm skin incision with a 60° inclination to the metatarsal axis was made over the medial aspect of the first metatarsal neck, and blunt dissection was performed to expose the metatarsal neck [3,4]. The periosteum was then incised and denuded [3]. Wedge osteotomy was performed at the metatarsal neck; the distal cut was perpendicular to the metatarsal shaft, and the base of the wedge was 7-mm wide (Fig. 2) [5].  A 2-mm K-wire was used to penetrate the medial side of the skin at the level of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, which was advanced retrogradely and subcutaneously toward the osteotomy site [6]. The metatarsal head was abducted and pushed laterally using the K-wire such that the first ray was as straight as possible (Fig. 3).

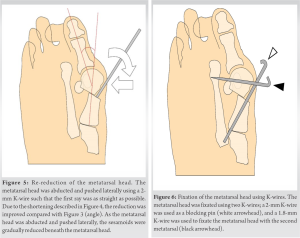

A 2-mm K-wire was used to penetrate the medial side of the skin at the level of the first metatarsophalangeal (MTP) joint, which was advanced retrogradely and subcutaneously toward the osteotomy site [6]. The metatarsal head was abducted and pushed laterally using the K-wire such that the first ray was as straight as possible (Fig. 3).  As the reduction of the hallux was insufficient, the end of the proximal fragment of the first metatarsal was resected and shortened by 6 mm (Fig. 4), which made the abduction and lateral pushing of the metatarsal head somewhat easier; however, a complete reduction was not accomplished due to the severe deformity (Fig. 5).

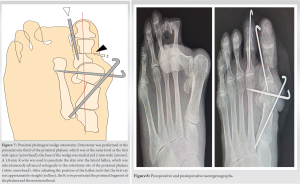

As the reduction of the hallux was insufficient, the end of the proximal fragment of the first metatarsal was resected and shortened by 6 mm (Fig. 4), which made the abduction and lateral pushing of the metatarsal head somewhat easier; however, a complete reduction was not accomplished due to the severe deformity (Fig. 5). To avoid transfer metatarsalgia, further resection of the first metatarsal was not performed. Keeping the metatarsal head abducted and pushed laterally as much as possible, the K-wire was advanced retrogradely from the metatarsal shaft to the base. The metatarsal head and second metatarsal were fixed using a 1.8-mm K-wire (Fig. 6) [3]. A 2-cm skin incision with a 75° inclination to the proximal phalanx axis was made over the medial aspect of the proximal one-third of the proximal phalanx, and blunt dissection was performed to expose the bone [3,7]. The periosteum was incised and denuded, and wedge osteotomy was performed at one-third of the proximal phalanx, which was at the same level as the first web space; the base of the wedge was medial and 2-mm wide (Fig. 7) [8].

To avoid transfer metatarsalgia, further resection of the first metatarsal was not performed. Keeping the metatarsal head abducted and pushed laterally as much as possible, the K-wire was advanced retrogradely from the metatarsal shaft to the base. The metatarsal head and second metatarsal were fixed using a 1.8-mm K-wire (Fig. 6) [3]. A 2-cm skin incision with a 75° inclination to the proximal phalanx axis was made over the medial aspect of the proximal one-third of the proximal phalanx, and blunt dissection was performed to expose the bone [3,7]. The periosteum was incised and denuded, and wedge osteotomy was performed at one-third of the proximal phalanx, which was at the same level as the first web space; the base of the wedge was medial and 2-mm wide (Fig. 7) [8]. A 1.8-mm K-wire was used to penetrate the skin over the lateral hallux, which was subcutaneously advanced retrogradely to the osteotomy site of the proximal phalanx [7]. After adjusting the position of the hallux such that the first ray was approximately straight, the K-wire penetrated the proximal fragment of the phalanx and metatarsal head (Fig. 8). After the two wounds were washed with saline, they were sutured using 5-0 nylon sutures. The second toe was corrected with closed wedge osteotomy at the proximal phalanx and fixed with a 1.6-mm K-wire. Finally, a postoperative roentgenograph was obtained (Fig. 8). Walking with shoes that restricted forefoot bearing was initiated 1 day after surgery [9]. The K-wires were removed 6 weeks after surgery and subsequently, range of motion exercises and full weight bearing were initiated [9]. Unrestricted activities were permitted 3 months postoperatively. After 4.1 years of follow-up, the HVA and IMA were 16° and 13°, respectively. The patient was highly satisfied with the results.

A 1.8-mm K-wire was used to penetrate the skin over the lateral hallux, which was subcutaneously advanced retrogradely to the osteotomy site of the proximal phalanx [7]. After adjusting the position of the hallux such that the first ray was approximately straight, the K-wire penetrated the proximal fragment of the phalanx and metatarsal head (Fig. 8). After the two wounds were washed with saline, they were sutured using 5-0 nylon sutures. The second toe was corrected with closed wedge osteotomy at the proximal phalanx and fixed with a 1.6-mm K-wire. Finally, a postoperative roentgenograph was obtained (Fig. 8). Walking with shoes that restricted forefoot bearing was initiated 1 day after surgery [9]. The K-wires were removed 6 weeks after surgery and subsequently, range of motion exercises and full weight bearing were initiated [9]. Unrestricted activities were permitted 3 months postoperatively. After 4.1 years of follow-up, the HVA and IMA were 16° and 13°, respectively. The patient was highly satisfied with the results.

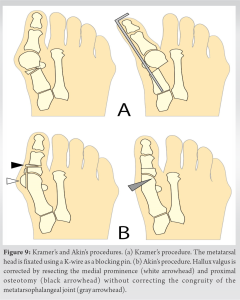

This case report presents the outcomes of the distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies fixated with K-wires without a soft tissue procedure for treating a 52-year-old patient with severe hallux valgus and an HVA of 80° [10]. These osteotomies were modifications of Kramer’s distal metatarsal osteotomy and Akin’s proximal phalangeal osteotomy (Fig. 9) [11,12]. The concept behind the osteotomy performed in this patient is that the distal metatarsal osteotomy primarily corrects the hallux valgus, and when the correction is insufficient (Fig. 6), the proximal phalanx osteotomy complements it (Fig. 7). In the present technique, correction of severe hallux valgus was performed using osteotomies without using a soft tissue procedure. In general, commonly used procedures for treating severe hallux valgus are proximal metatarsal osteotomies or tarsometatarsal arthrodesis combined with a soft tissue procedure [1,2], where the proximal osteotomies correct the IMA but not the HVA, meaning that, the soft tissue procedure alone corrects the HVA. However, correction of severe hallux valgus using soft tissue procedure alone is ineffective; the more severe the hallux valgus is, the more difficult it is to correct. Moreover, invasive soft tissue procedures may cause necrosis of the metatarsal head and postoperative hallux varus deformities. However, in the present study, the soft tissue procedure was not performed, and thus, these complications may be lower. In the present technique, the correction was performed so that the first ray is approximately straight. The straight line was approximately in the same direction as the flexor hallucis longus (FHL) tendon; therefore, the hallux plantar flexes in the same direction as the FHL without overlapping the second toe. During surgery, as the metatarsal head was abducted and pushed laterally, the sesamoids were gradually reduced beneath the metatarsal head (Fig. 5). This suggests that the FHL and FH brevis (FHB) was aligned with the first ray. However, for managing severe hallux valgus, such as in this case, the sesamoids were not completely reduced. Proximal phalanx osteotomy is then performed such that the first ray is straight. After performing the two osteotomies, the hallux was plantar flexed approximately on the plane of the first ray owing to the traction force of the FHL, although the base of the proximal phalanx slightly deviated laterally owing to the traction force of the FHB (Fig. 7). Congruity of the first MTP joint was not corrected in this patient because (1) the correction of joint congruity requires a soft tissue procedure. However, a severe deformity requires a highly invasive soft tissue procedure, which could cause necrosis of the metatarsal head and postoperative hallux varus; (2) most patients with hallux valgus do not have pain associated with joint incongruity; and (3) joint congruity is not needed for plantar flexion of the hallux without overlapping the second toe: When the first ray was surgically arraigned approximately straight, the hallux plantar flexes approximately on the plane of the first ray due to the mechanism described above. Furthermore, in both Kramer’s and Akin’s procedures, joint congruity is not corrected (Fig. 9). In the Kramer’s procedure, the first ray is straightened by abduction and pushing the metatarsal head laterally [11], and in the Akin’s procedure, the first ray is straightened by resecting the medial prominence and proximal phalanx osteotomy [13] (Akin’s procedure is widely recognized for correcting hallux valgus interphalangeus [1,2]; however, the original Akin’s procedure was used for correcting hallux valgus deformity without correcting joint congruity [12,13]. I believe that the use of K-wires for fixation is advantageous in hallux valgus surgery, which is listed as follows: (1) When the stability of the osteotomy site after fixation is insufficient, K-wires can be added; (2) the adjacent bone (e.g., medial cuneiform, second metatarsal, etc.) can be used for fixation; (3) soft tissue can be used for fixation with K-wires by penetrating the wire through the subcutaneous soft tissue, similar to Kramer’s procedure; and (4) the flexibility and elasticity of K-wires allow for minor correction of the alignment of the osteotomized bones by manipulating the hallux after fixation. I present a case of severe hallux valgus with an HVA of 80° treated with distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies without a soft tissue procedure. I believe that this method is effective for all cases of severe hallux valgus if surgeons can adjust the amount of bone resection and the number of K-wires used in each patient.

Distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies without a soft tissue procedure are effective for treating a patient with severe hallux valgus.

Distal metatarsal and proximal phalangeal osteotomies fixated with K-wires without soft tissue procedure for severe hallux valgus can achieve an adequate correction.

References

- 1.Ray JJ, Friedmann AJ, Hanselman AE, Vaida J, Dayton PD, Hatch DJ, et al. Hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Orthop 2019;4:2473011419838500. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Coughlin MJ, Anderson RB. Hallux valgus. In: Coughlin MJ, Saltzman CL, Anderson RB, editors. Mann’s Surgery of the Foot and Ankle. 9th ed. Philadelphia, PA: Elsevier Saunders; 2004. p. 467-925. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Nakajima K. Sliding oblique metatarsal osteotomy fixated with K-wires without cheilectomy for all grades of hallux rigidus: A case series of 76 patients. Foot Ankle Orthop 2022;7:24730114221144048. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Iannò B, Familiari F, De Gori M, Galasso O, Ranuccio F, Gasparini G. Midterm results and complications after minimally invasive distal metatarsal osteotomy for treatment of hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Int 2013;34:969-77. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Angthong C, Yoshimura I, Kanazawa K, Hagio T, Ida T, Naito M. Minimally invasive distal linear metatarsal osteotomy for correction of hallux valgus: A preliminary study of clinical outcome and analytical radiographic results via a mapping system. Arch Orthop Trauma Surg 2013;133:321-31. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Lynch FR. Applications of the opening wedge cuneiform osteotomy in the surgical repair of juvenile hallux abducto valgus. J Foot Ankle Surg 1995;34:103-23. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Basile A, Battaglia A, Campi A. Comparison of Chevron-Akin osteotomy and distal soft tissue reconstruction-Akin osteotomy for correction of mild hallux valgus. Foot Ankle Surg 2000;6:155-63. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Ferrari J. Interventions for treating hallux valgus (abductovalgus) and bunions. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2000;2:CD000964. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Nakajima K. Sliding oblique metatarsal osteotomy fixated with a K-wire without cheilectomy for hallux rigidus. J Foot Ankle Surg 2022;61:279-85. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Goucher NR, Coughlin MJ. Hallux metatarsophalangeal joint arthrodesis using dome-shaped reamers and dorsal plate fixation: A prospective study. Foot Ankle Int 2006;27:869-76. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Magnan B, Bortolazzi R, Samaila E, Pezzè L, Rossi N, Bartolozzi P. Percutaneous distal metatarsal osteotomy for correction of hallux valgus. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:135-48. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Kelikian H. Osteotomy. In: Hallux Valgus, Allied Deformities of the Forefoot and Metatarsalgia. Philadelphia, PA, London: W.B. Sanders Company; 1965. p. 163-204. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Akin OF. The treatment of hallux valgus. A new operative procedure and its results. Med Sentinel 1925;33:678-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]