Older children with complex supracondylar fracture, need proper monitoring and early rehabilitation to prevent elbow stiffness.

Dr. Amit Kumar, Department of Orthopaedics, Sanjay Gandhi Postgraduate Institute of Medical Sciences, Lucknow, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: amit2k03@gmail.com

Introduction: Traditionally displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus are treated by percutaneous pinning and above-elbow slab/cast support. Crossed pinning is commonly used as it provides better biomechanical stability than lateral pinning. The fracture is often associated with a high risk of complications such as neurovascular injury, pulselessness, and the development of swelling or compartment syndrome in acute scenarios. These clinical conditions require regular examination of neurovascular structures and forearm swelling, which is difficult with a slab or cast. Post-surgery Slab or cast has been found to be associated with elbow stiffness, which significantly increases in older children. Here we are presenting an innovative fixation method for such fracture.

Materials and Methods: This retrospective study examined the clinical, radiological, and functional results of ten patients who had displaced supracondylar humerus fractures treated with our novel Arc fixator.

Results: 6 out of 10 patients (mean age: 8.2 years; 6–12 years) had a fracture of the non-dominant limb. Flexion injury was seen in one patient with transient ulnar nerve palsy. 3 patients who had injury-related nerve palsy (median 2/ulnar 1), recovered spontaneously at 3 months. Fracture union was observed in all at 6 weeks. All patients achieved a near-normal range of motion (ROM) without deformity at the final follow-up. They had satisfactory scores at 3 months according to Flynn criteria.

Conclusion: The construct was found stable and rigid enough to provide fracture stability and allow intermittent ROM exercises. This new method of fixation has the added advantage of regular examination of forearm and neurovascular structures in the postoperative period and allowing early elbow function of the patient, along with being patient-friendly.

Keywords: External fixator, supracondylar fracture, elbow stiffness, children, K-wires.

Supracondylar humerus fracture in pediatrics, is a major injury around the elbow which is associated with a high risk of complications [1]. Due to proximity and risk to neurovascular structures, it is considered a fracture of utmost urgency. Displaced or open fractures may present as limb-threatening conditions of compartment syndrome, brachial artery injury, or nerve injury. Late complications include malunion or cubitus varus deformity. This fracture is encountered in all pediatric age groups, predominantly in male children aged 5–7 years old [2]. Posterior displacement is found in the extension type (95%) of fracture, whereas anterior displacement occurs in the flexion type (5%) [1,2]. Displaced fractures (modified Gartland III and IV) are highly unstable fractures and need operative intervention (closed or open reduction and pinning). Closed pinning is routinely attempted, with crossed pinning preferred over lateral pinning as it is biomechanically superior [3]. Post-surgery, the elbow is immobilized in a slab support for 3–6 weeks till signs of union are visible on X-ray. Post-surgery, a slab or cast in older children has been found to be associated with elbow stiffness. Therefore, recovery of the elbow joint is slower in older children, and rehabilitation is often needed to restore normal joint function. According to Fletcher et al. [4], older children require nearly 4 times more physical therapy to manage residual stiffness. Keppler et al. reported that the early elbow function alleviates the risk of stiffness and normalizes life early [5]. The presence of swelling, open fracture, or primary neurological or vascular problems (“pulseless pink hand”) also warrants cast-free management of the limb for regular evaluation. Migration of the pin is also a very common complication associated with free ends of pin [6]. Taller introduced the use of an external fixator for supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children in 1986 [7]. In 2008, Slongo published his series of Gartland type II supracondylar humeral fractures treated with a lateral external fixator, and this technique has been promoted as a safe alternative to Kirschner wire fixation [8]. However, cases of radial nerve injury by proximal pin have been reported [9]. We are introducing an innovative external fixator that does not require any additional pin placement in the proximal fragment and provides a stable construct allowing cast-free early elbow range of motion (ROM) post-surgery.

This is a retrospective study where clinical data of patients, treated for supracondylar humerus fractures with closed reduction and Arc fixator from 2022 to 2024 in our department, were analyzed. In this study, we reviewed all the patient’s records during In patient and outpatient follow-up for the demographic data (age, gender, and mechanism of injury), site of injury, type of fracture, presence of anterior skin contusion or wound, radial pulse status, neurological injury, post-surgery complications (pin-tract infection, nerve palsy, and compartment syndrome) ROM, X-rays findings. This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and was approved by our institution’s research ethics committee.

Inclusion criteria

Patient with Elbow Injury with the age group of 6–12 years; Isolated Type III/IV supracondylar humeral fracture; Irreducible type II Fracture.

Exclusion criteria

Ipsilateral other associated fracture of humerus, forearm; Polytrauma injury; Open fracture (Gustilo Grade II/III). A comprehensive neurovascular assessment and rigorous clinical examination were performed as soon as the patient arrived in the hospital. The standard anteroposterior and lateral radiographs of the affected elbow were obtained, and the type of fracture was documented. With informed written consent, the patients were operated as emergency case.

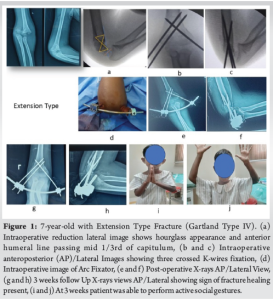

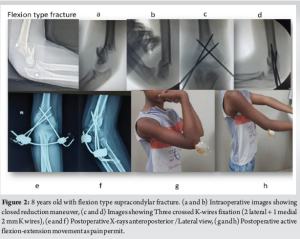

All surgeries were done under general anesthesia. Surgery was conducted by the same orthopedic specialist to avoid interpersonal discrepancies. The patient was positioned supine with the affected upper limb at the edge of the table. The affected elbow was rested on a radiolucent forearm rest and an image intensifier was placed within it for anteroposterior (AP) and lateral view. After satisfactory closed reduction in AP, JONES, and lateral view, K wires were placed in a crossed pinning fashion with two 2 mm Kirschner wires from the lateral side and one 2 mm K wire from the medial side. Satisfactory reduction was defined by the absence of medial or lateral translation and Varus or valgus angulation in AP or JONES view. In lateral view, the hourglass appearance of the olecranon fossa was restored to avoid any malrotation with the anterior humeral line passing through the mid 1/3rd of the capitulum (Fig. 1). Once wires were properly placed, the reduction was rechecked in AP and Lateral view with forearm extended. Then individual K-wires were clamped using 3 Beta clamps to an appropriate length curved JESS ROD of 3 mm with concavity towards the elbow to accommodate it. After applying the Arc fixator, the elbow ROM was assessed to allow functional ROM. Pin site dressing was done and Cuff collar sling was applied.

Post-surgery rehabilitation

Patients were evaluated for swelling around the elbow or forearm, distal pulse, and any neurological deficit. Patients were encouraged to start ROM the next day with passive and active assisted support as pain permitted. The X-ray and dressing of the wound or pin site were changed on post-surgery day 2. Patients were discharged with sling support with advice to continue intermittent passive assisted ROM. They were advised to return after 3 weeks for a clinical evaluation and X-rays to look for signs of union or any complications such as pin site infection or loosening of the pin or fixator, and to maintain full ROM and do daily light activities. They were again reviewed at 6 weeks and if visible callus was present, the fixator was removed. ROM, any complication such as infection, and X-rays for consolidation of union or any radiological change like myositis ossificans were noted. Parents were asked to encourage their children to actively follow ROM exercise. They were asked to revisit after 3 months of index surgery for further follow-up. The treatment outcomes at 3 months were assessed using Flynn’s criteria, which assessed the carrying angle and ROM of the affected elbow.

Outcome measurement

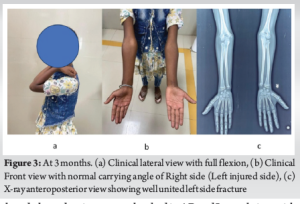

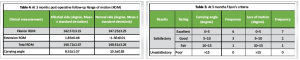

Functional and cosmetic outcomes were assessed based on Flynn’s criteria [10], at the final follow-up examinations at 3 months which evaluate loss of motion, carrying angle, and malalignment.

Statistical analysis

Numerical data were collected using an Excel worksheet (Microsoft Corp., Redmond, WA, USA). Categorical variables were presented as frequency and percentage, and continuous variables were presented as mean standard deviation [median and interquartile range].

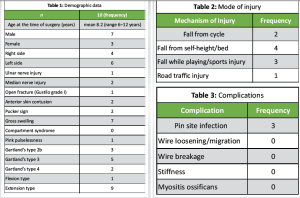

A total of ten patients (seven males and three females) were included in this study. All patients were between 6 and 12 years of age, with a mean age of 8.2 years (Table 1). All patients were right-hand dominant. The majority of the patients had their nondominant upper limbs injured (6/10). Open fracture (Gustilo grade I) was observed in one case with pink pulselessness. Gross swelling of the elbow was seen in displaced fractures (7/10) with signs of anterior skin contusion (2), pucker sign (2), and pink pulselessness (1) in association with ulnar (1) and median (2) nerve injury. Ulnar nerve injury was seen in one case with flexion-type injury (Fig. 2). All nerve injuries were injury-related and recovered within 3 months of injury. Most of the patients had sustained fractures after fall (9/10), with only one patient had a road traffic injury (Table 2). All patients had surgical fixation of the fracture within 24–72 h of injury. All patients were discharged on 3rd postoperative day. The patients were reviewed on 3rd week postoperatively to look for any signs of pin site infection (3/10) and other wire-related issues (Table 3). The external fixator was removed in all cases at 6 weeks post-operatively with radiological signs of union. Parents were asked to encourage their children to actively follow ROM exercise. They were again reviewed at 3 months for final assessment. At final assessments, all patients had achieved union (Fig. 3). The treatment outcomes were assessed using Flynn’s criteria, which assessed the carrying angle and ROM of the affected and normal elbow (Table 4). All the patients achieved satisfactory outcomes in terms of cosmetic and functional aspects (Table 5). In terms of cosmetic factors, six patients had excellent outcomes, while three patients had good outcomes, and one patient a fair outcome. In terms of functional factor, seven patients had excellent outcomes, while two had good outcomes. One patient with sustained pin site infection at 3 weeks had a fair outcome with resolution of infection at 6 weeks. All parents were satisfied with the treatment outcomes.

Closed reduction and percutaneous pinning are the most common surgical methods for treating displaced supracondylar fracture. In order to minimize postoperative deformity, the distal fragment must be reduced and fixed almost anatomically. In their biomechanical investigation, Weinberg et al. demonstrated that under cyclic loading, crossed K-wires exhibited the maximum stiffness and the least amount of reduction loss [11]. Li et al. discovered that the lateral external fixator and three crossed K-wires did not significantly vary in extension, rotation, or varus loading (P > 0.05) and that the fixator’s stability was worse than that of the three crossed K-wires in valgus loading. Given these biomechanical findings Crossed pinning is preferred over lateral pinning or lateral external fixator for better biomechanical stability [12]. However, it carries the narrow risk of ulnar nerve injury up to 3–4%. This is decreased to 0.4–1.8% if a mini-open approach is used for the medial wire [13]. We operated all displaced fractures or irreducible fractures within 24–72 h with three crossed K-wires. As delay beyond 3 days has been associated with difficult closed reduction and may require open reduction, which carries a high risk of joint stiffness and myositis ossificans. After reduction, crossed pinning with two 2 mm Kirschner wires from the lateral side and one 2 mm K-wire from the medial side was done in all cases. Preoperative ulnar nerve injury characterized by poor hand grip was reported in one case with flexion-type injury. Two cases with median nerve injury had posterolateral displacement, which subsequently improved by 3 months. In displaced supracondylar fractures, postoperative palsy of the median and ulnar nerve is frequent and can surpass 10% [14]. These injuries typically heal on their own in 8–12 weeks since they are caused by the traction of the nerve during the fracture. In our study, overall incidence of nerve injury before surgery was 30% which is comparatively high due to the small sample size. Because artery entrapment is more common when these lesions are present, early correction should be taken into consideration [15]. Radial nerve lesions are a distinct problem in supracondylar fractures since traction injuries to this nerve are found in posteromedial displacement. An observation period of 8 weeks is fair if iatrogenic injuries, resulting from the surgical approach can be ruled out. There was no radial nerve injury in our cases and no iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury was observed in our study with percutaneous anterior to epicondyle placement of wire. Pin-tract infection rates in patients having percutaneous K-wiring range from 0% to 8%, according to prior research [16]. In our series, three out of ten patients had a superficial pin site infection, which cleared after 1 week of oral antibiotics with no additional complications. These 3 patients after discharge from hospital had poor compliance to pin-site care. After the plaster cast is taken off, the elbow joint’s ROM may be limited to a certain extent. Stiffness can be a complication of any elbow fracture and occurs in 3–6% of supracondylar fractures, mainly due to immobilization imposed by a slab or cast [17]. The exact percentage may vary based on the procedure employed, the severity of the fracture, and individual patient characteristics. By 6 months following closed reduction and percutaneous pinning of a displaced, uncomplicated supracondylar humerus fracture, children should have returned to 94% of their normal elbow ROM. Improvement may continue for up to a year after surgery [18]. Interestingly, children tend not to move the affected limb due to fear or pain. Keppler et al. and Jandrić have reported that early elbow function alleviates the risk of stiffness and normalizes life early [5,19]. Studies have supported the need for early rehabilitation of older children with supracondylar fractures, resulting in better elbow function and decreased stiffness. Patients can begin elbow function exercises earlier when an external fixation is used instead of the more conventional pinning and plaster cast method. According to the study’s findings, older children who received an external fixation recovered their elbow function effectively and without stiffness [20]. Furthermore, because no plaster cast was required after the treatment, the children’s comfort level improved significantly, and the affected elbow was able to move within an acceptable range. For cast-free elbow, we applied the Arc fixator and found no elbow stiffness in our study at 3 months. External fixation is a proven method for fractures at different locations. In 1986, Taller pioneered the use of an external fixator for children’s supracondylar humeral fractures [7]. Since then, several fixator types for supracondylar fractures have been described. Compared to the crossed K-wires approach, Slongo’s unilateral external fixator, which does not need elbow spanning, is more straightforward and biomechanically stable. Nonetheless, there have been documented instances of proximal pin-induced radial nerve damage [9]. Our fixation technique eliminates the need for an extra proximal lateral pin, in contrast to the Slongo’s external fixator. Consequently, avoid any danger of iatrogenic radial nerve damage. This technique offers a new approach that combines biomechanical stability with the ability for early ROM exercises, potentially reducing the risk of postoperative complications such as elbow stiffness.

A safe and effective surgical treatment option for older children with supracondylar humeral fractures is the Arc Fixator. It allows early elbow mobility following surgery, avoiding elbow stiffness and ensuring adequate fracture healing. For older children and adolescents, early rehabilitation therapy following external fixation can significantly speed up elbow joint healing, improve patient quality of life, and facilitate a prompt return to normal life. Unlike other methods of external fixators, the Arc fixator does not require an image intensifier during construct preparation and avoids any extra incision laterally with no chance of radial nerve injury.

Limitations

A small sample size, the retrospective nature of the study, and the absence of a control group are a few limitations of this study. Further comparative study with a large sample size would strengthen the findings of this study.

Arc fixator as an alternative to pinning and casting for the treatment of supracondylar humerus fractures in older children provides a stable construct, allows better monitoring of complications, and prevents elbow stiffness by restoring early elbow mobility.

References

- 1.Yellin JL, England P, Flynn JM. Supracondylar humerus fractures in children. In: Abzug JM, Kozin S, Zlotolow DA, editors. The Pediatric Upper Extremity. New York: Springer; 2023. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Stans AA. Supracondylar fractures of the elbow in children. In: Morrey BF, Sanchez-Sotelo J, Morrey ME, editors. Morrey’s The Elbow and Its Disorders. 5th ed. Netherlands: Elsevier; 2018. p. 25371. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Bloom T, Robertson C, Mahar AT, Newton P. Biomechanical analysis of supracondylar humerus fracture pinning for slightly malreduced fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2008;28:766-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Fletcher ND, Schiller JR, Garg S, Weller A, Larson AN, Kwon M, et al. Increased severity of type III supracondylar humerus fractures in the preteen population. J Pediatr Orthop 2012;32:567-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Keppler P, Khaled S, Birte S, Kinzl L. The effectiveness of physiotherapy after operative treatment of supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Pediatr Orthop 2005;25:314-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Bashyal RK, Chu JY, Schoenecker PL, Dobbs MB, Luhmann SJ, Gordon JE. Complications after pinning of supracondylar distal humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2009;29:704-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Taller S. Use of external fixators in the treatment of supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Acta Chir Orthop Traumatol Cech 1986;53:508-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Slongo T, Schmid T, Wilkins K, Joeris A. Lateral external fixation--a new surgical technique for displaced unreducible supracondylar humeral fractures in children. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1690-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Horst M, Altermatt S, Weber DM, Weil R, Ramseier LE. Pitfalls of lateral external fixation for supracondylar humeral fractures in children. Eur J Trauma Emerg Surg 2011;37:405-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Flynn JC, Matthews JG, Benoit RL. Blind pinning of displaced supracondylar fractures of the humerus in children. Sixteen years’ experience with long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Am 1974;56:263-72. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Weinberg AM, Castellani C, Arzdorf M, Schneider E, Gasser B, Linke B. Osteosynthesis of supracondylar humerus fractures in children: A biomechanical comparison of four techniques. Clin Biomech (Bristol) 2007;22:502-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.Li WC, Meng QX, Xu RJ, Cai G, Chen H, Li HJ. Biomechanical analysis between Orthofix® external fixator and different K-wire configurations for pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. J Orthop Surg Res 2018;13:188. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Al Habsi S, Al Hamimi S, Al Musawi H, Rao KS, Ajemi Al, Sharaby M. Does a medial mini-incision decrease the risk of iatrogenic ulnar nerve injury in pediatric supracondylar humeral fractures treated with closed reduction and percutaneous pinning? A retrospective cohort study. Curr Orthop Pract 2021;32:326-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Norrell KN, Muolo CE, Sherman AK, Sinclair MK. The frequency and outcomes of nerve palsies in operatively treated supracondylar humerus fractures. J Pediatr Orthop 2022;42:408-12. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Blakey CM, Biant LC, Birch R. Ischaemia and the pink, pulseless hand complicating supracondylar fractures of the humerus in childhood: Long-term follow-up. J Bone Joint Surg Br 2009;91:1487-92. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Parikh SN, Lykissas MG, Roshdy M, Mineo RC, Wall EJ. Pin tract infection of operatively treated supracondylar fractures in children: Long-term functional outcomes and anatomical study. J Child Orthop 2015;9:295-302. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Gausepohl T, Mader K, Pennig D. Mechanical distraction for the treatment of posttraumatic stiffness of the elbow in children and adolescents. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2006;88:1011-21. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Zionts LE, Woodson CJ, Manjra N, Zalavras C. Time of return of elbow motion after percutaneous pinning of pediatric supracondylar humerus fractures. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2009;467:2007-10. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Jandrić S. Effects of physical therapy in the treatment of the posttraumatic elbow contractures in the children. Bosn J Basic Med Sci 2007;7:29-32. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.He M, Wang Q, Zhao J, Wang Y. Efficacy of ultra-early rehabilitation on elbow function after Slongo’s external fixation for supracondylar humeral fractures in older children and adolescents. J Orthop Surg Res 2021;16:520. [Google Scholar | PubMed]