Precise tumor excision and cavity reconstruction using the sandwich technique with bone cement and gel foam resulted in a favorable functional outcome in a young female.

Dr. B Mohan Choudhary, Department of Orthopaedic Surgery, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: drchoudharyortho@yahoo.com

Introduction: Giant cell tumor (GCT) of bone is a benign but locally aggressive neoplasm, commonly affecting the epiphysio-metaphyseal regions of long bones in young adults. The proximal tibia is among the most frequent sites. Management is challenging due to the tumors high recurrence potential and its location near weight-bearing joints.

Case Report: A 22-year-old female presented with a 5-month history of pain and swelling over the right knee. Imaging revealed an epiphysio-metaphyseal osteolytic lesion in the proximal tibia with an anterior cortical breach, confirmed on computed tomography and magnetic resonance imaging. Surgical management included extended intralesional curettage through an anteromedial approach. The tumor cavity was treated with high-speed burr, hydrogen peroxide lavage to prevent local recurrence and filled the cavity using sandwich technique with polymethyl methacrylate bone cement and gel foam.

Results: Post-operative recovery was better. The patient was started on partial weight-bearing in 1 week and full weight-bearing by 2 weeks. Patient achieved nearly the full range of movements at the knee by 8 weeks. Histopathology confirmed the diagnosis of GCT. At 1-year follow-up, the patient showed no clinical or radiological signs of recurrence, with an excellent functional outcome.

Conclusion: Extended curettage with adjuvant therapy and bone cementing through the sandwich technique offers a joint-preserving and effective treatment for GCTs of the proximal tibia, even in the presence of cortical breach. A long-term follow-up is essential to monitor for local recurrence or pulmonary metastasis.

Keywords: Giant cell tumor, cortical Giant cell tumor, cortical breech, bone cementing, sandwich technique, recurrence.

Giant cell tumor (GCT) is the most common benign bone tumor encountered by an orthopaedic surgeon. It exhibits a wide biological spectrum, ranging from benign behavior to high recurrence rates and, in rare cases with malignant transformation [1]. GCT represents approximately around 5% of all primary bone tumors [1,2]. GCT occurs in skeletally mature individuals, with its peak incidence in the third decade [3]. Various classification systems based on histological, clinical, and radiographic features have been suggested; however, they offer limited prognostic value in predicting the likelihood of local recurrence [1,4]. It typically involves the epiphysio-metaphyseal region of long bones [1,5]. The presenting complaint will be pain of variable severity that may be associated with a mass present from few weeks to several months [1,4]. On plain radiographs, GCTs of long bones typically present as lytic lesions originating in the epiphysis, with extension into the metaphysis and often reaching near the adjacent subchondral bone [1,3]. GCT of bone is composed of polygonal mononuclear stromal cells, spindle-shaped fibroblasts, and multinucleated giant cells resembling osteoclasts [6]. Without adequate resection, the rate of recurrence in GCT is high [1,6]. Curettage has long been the standard treatment for GCT; however, it carries a relatively high risk of local recurrence, with rates reaching up to 35–40% [1,6]. The increased recurrence has been reduced by use of local adjuvants such as cryosurgery, phenol, bone cement, and hydrogen peroxide [1,3,4,7]. Intralesional curettage with a better cortical window provides a good functional outcome and remains the treatment of choice in many patients [2,8]. The goal is to maximize functional preservation and minimize the chance of recurrence [1,3,7]. After curettage, the cavity filling depends on the cortical circumference and the size of the subchondral bone [3,7]. Hereby presenting a case of a 22-year-old girl with proximal tibia GCT managed with extended curettage and cavity filling with the sandwich technique.

A 22-year-old girl presented with complaints of pain and swelling over her right knee for the past 5 months. The patient also complains of difficulty in squatting. No history of trauma or any other systemic illness. On clinical examination of her right knee, swelling of size 3 × 2 cm is present over the proximal one-third of the anterior aspect of the leg. No local warmth. No signs of inflammation. Tenderness is present over the proximal one-third of the tibia. The range of motion (ROM) of her right knee was 0–80° (further painful). Distal pulses were felt. Sensations were intact. Laboratory tests showed mildly elevated C-reactive protein to 2.1 mg/dL and erythrocyte sedimentation rate of 8. Plain radiograph of the right knee (Fig. 1) showed an eccentric osteolytic epiphysio-metaphyseal lesion of the right proximal tibia with a doubtful breach of the anterior cortex.

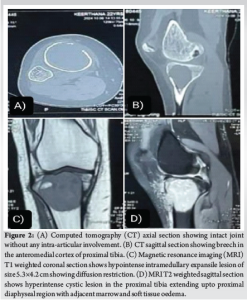

Computed tomography screening (Fig. 2 a and b) was done to rule out the involvement of cortical breech, which confirmed the anterior cortical breech over the proximal tibia.

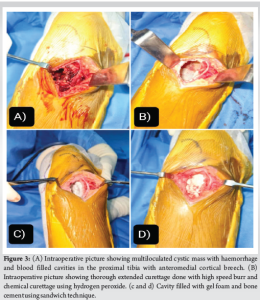

Magnetic resonance imaging of the right knee-T1 weighted (Fig. 2c) shows a hypointense intramedullary expansile lesion of size 5.3 × 4.2 cm showing diffusion restriction. T2-weighted (Fig. 2d) shows a hyperintense cystic lesion extending up to the proximal diaphyseal region with adjacent marrow and soft tissue oedema. After thorough pre-operative planning, the patient was taken up for surgery. Proximal tibia anteromedial approach was used for the patient, keeping the possibility of anteromedial cortical breech, and soft tissues were dissected. The proximal tibia was exposed to trace the boundaries of the lesion. The anteromedial cortex was found to be breached and found to be a multiloculated cystic mass with haemorrhage and blood-filled cavities (Fig. 3a). The involved cortex was nibbled out to enter the cavity of the lesion. Complete, thorough curettage was done with the bone gouge. The inner and outer margins are curetted with the highspeed burr. The cavity was thoroughly washed with hydrogen peroxide repeatedly for thermal necrosis of the remnant tumor cells (Fig. 3b). Subchondral bone was found to be intact which confirmed that the joint was preserved. Using sandwich technique, cavity was first filled with gel foam, polymethylmethacrylate (PMMA) bone cement and gel foam optimally to fill up the dead space in the cavity (Fig. 3c and d). Once the cement was set, wound wash was given to the surrounding soft tissues. The curetted tissue sample was sent for culture and histopathological studies. Intraoperative and post-operative periods were uneventful.

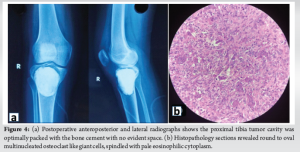

Post-operative anteroposterior and lateral radiograph (Fig. 4a) had shown that the proximal tibia tumor cavity was optimally packed with the bone cement.

Histopathology section (Fig. 4b) revealed round to oval multinucleated osteoclast like giant cells, spindled with pale eosinophilic cytoplasm these features were strongly suggestive of GCT.

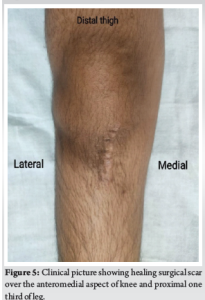

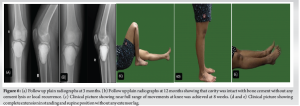

Surgical wound was found to be healed postoperatively (Fig. 5). Gentle right knee ROM was started on post-operative day 3. Initial range of movements of right knee were 0–70°. Partial weight bearing with right lower limb was started after 1 week. Complete weight bearing with right lower limb was started after 2 weeks. She achieved nearly full right knee range of movements till 110° by 8 weeks without any pain or restriction. She was rehabilitataed to her normal routine and activities with musculoskeletal tumor society score of 8. The patient was on 1-year follow-up. Follow-up plain radiograph at 3 months and 12 months shows that bone cement was intact without any local recurrence and lysis (Fig. 6a and b). She was able to perform normal activities with complete knee flexion (Fig. 6c) and no extensor lag (Fig. 6d and e). The patient was also able to do her recreational activities without any restrictions. The patient was adviced for a routine follow-up every 2 months to assess for any recurrence. Recurrence will be checked by clinical examination (to look for any new lump, tenderness around the surgical site) and radiological imaging such as X-ray (to look for any bony recurrence around the previous tumor site) and MRI scan (if suspected soft tissue involvement and to assess the extent of recurrence).

GCT is a benign but locally aggressive bone tumor that typically affects the ends of long bones [1]. GCT most commonly occurs in individuals in their third decade of life, after the closure of the physis [1,4]. This report highlights GCT in a 22-year-old female patient. GCT’s clinical behavior is unpredictable, with symptom severity often not correlating with its radiographic or histological appearance [8]. This variability makes early diagnosis challenging. Patients commonly present with pain, terminally restricted joint movements, and a thickened bone with a palpable “eggshell crackling” cortex [1]. In 15% of cases, the first indication of the tumor is a pathological fracture [5]. However, our patient presented only with diffuse knee pain, difficulty in walking for a prolonged distance. The diagnosis of GCT is mainly based on X-ray findings, which commonly show lytic expansile lesion in the epiphysio-metaphyseal region [1,9]. In this case, the tumor was located in the epi-metaphyseal region, as the proximal tibial physis had already fused. Imaging techniques like CT is superior in visualizing cortical discontinuity. MRI is better to see any surrounding soft-tissue oedema, type of signal intensities of the lesion and for surgical planning [10]. The primary goal of treatment is to achieve local disease control while preserving joint function [8]. The aggressive surgical approaches that aim to reduce the risk of recurrence are also associated with significant morbidity [2,6]. Wide surgical excision is highly effective, with recurrence rates reported at 0–5% [6]. However, this approach is typically limited to areas such as the distal ulna, proximal fibula, or distal radius, where limb function is less compromised [11]. For GCTs involving subchondral bone, en bloc resection often requires complex reconstruction, which can significantly impact joint function and quality of life [7,11,12]. Our case was found to be intact subchondral bone. For primary lesions, we recommend extended curettage, while wide excision with reconstruction is suggested for recurrent cases. Although curettage is effective, recurrence rates of 20–30% have been reported [4]. This highlights the need for adjuvant therapies, such as phenol, hydrogen peroxide, alcohol, liquid nitrogen, or methyl methacrylate, to eliminate residual tumor cells [1,3,4,7]. However, thorough curettage remains the most critical factor in reducing recurrence rates. Following curettage, the use of highspeed burr gives precise excision of tumor, potentially leading to clear margin [4,13]. The base is first covered with a layer of gel foam, after which the remaining cavity is filled with PMMA bone cement employing the sandwich technique [7, 8, 12-14]. The exothermic reaction during cement polymerization facilitates thermal necrosis of residual tumor cells [6,15]. Meticulous care must be taken during curettage to avoid unintended cortical breach or disruption of the posterior pseudo-capsule [3,7]. The posterior periosteum plays a crucial role as a barrier, effectively preventing the leakage of bone cement from the defect site [3]. Bone cement is a preferred option due to its cost-effectiveness, ability to support immediate weight-bearing, and utility in detecting recurrences through radiographs [5,13,15]. In our case, extended curettage followed by gel foam and bone cement application using sandwich technique yielded excellent results. At 1-year follow-up, the patient had no functional limitations or evidence of recurrence on imaging studies.

In summary, the effective management of GCTs in weight-bearing bones requires a precise surgical excision, cavity filling and thorough post-operative rehabilitation. This case report illustrates the success of such a strategy in treating a GCT in the proximal tibia of a 22-year-old female patient. Pre-operative radiological investigations and appropriate surgical approach has to be done to reduce the recurrence. The patient achieved favorable clinical outcomes, with regular follow-ups showing no signs of tumor recurrence. However, a minimum of 5 year follow up is recommended by the authors to rule out the pulmonary metastasis.

Giant cell tumor of bone, though benign, is locally aggressive and requires timely diagnosis and precise management to prevent recurrence and preserve joint function. Extended intralesional curettage combined with adjuvant therapies and bone cement reconstruction using the sandwich technique offers an effective, joint-sparing solution, particularly in primary lesions with intact subchondral bone. Thorough surgical curettage remains the cornerstone in minimizing recurrence, and post-operative imaging is vital for early detection of relapse.

References

- 1.Mavrogenis AF, Igoumenou VG, Megaloikonomos PD, Panagopoulos GN, Papagelopoulos PJ, Soucacos PN. Giant cell tumor of bone revisited. SICOT J 2017;3:54. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Palmerini E, Picci P, Reichardt P, Downey G. Malignancy in giant cell tumor of bone: A review of the literature. Technol Cancer Res Treat 2019;18:1533033819840000. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saibaba B, Chouhan DK, Kumar V, Dhillon MS, Rajoli SR. Curettage and reconstruction by the sandwich technique for giant cell tumours around the knee. J Orthop Surg 2014;22:351-5. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ruggieri P, Mavrogenis AF, Ussia G, Angelini A, Papagelopoulos PJ, Mercuri M. Recurrence after and complications associated with adjuvant treatments for sacral giant cell tumor. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2010;468:2954-61. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Wittig JC, Simpson BM, Bickels J, Kellar-Graney KL, Malawer MM. Giant cell tumor of the hand: Superior results with curettage, cryosurgery, and cementation. J Hand Surg Am 2001;26:546-55. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chawla S, Henshaw R, Seeger L, Choy E, Blay JY, Ferrari S, et al. Safety and efficacy of denosumab for adults and skeletally mature adolescents with giant cell tumour of bone: Interim analysis of an open-label, parallel-group, phase 2 study. Lancet Oncol 2013;14:901-8. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ashok MS, Saraf S, Sanapala KK, Ranganath M. Curettage and reconstruction by the sandwich technique for giant cell tumours around the knee. Int J Orthop Sci 2021;7:170-2. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kundu ZS, Gogna P, Singla R, Sangwan SS, Kamboj P, Goyal S. Joint salvage using sandwich technique for giant cell tumors around knee. J Knee Surg 2015;28:157-64. [Google Scholar]

- 9.ElDesouqi AA, Ragab RK, Ghoneim AS, Sabaa BM, Rafalla AA. Treatment of giant cell tumor of bone using bone grafting and cementation with versus without gel foam. Alexandria J Med 2022;58:78-54. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herman SD, Mesgarzadeh M, Bonakdarpour A, Dalinka MK. The role of magnetic resonance imaging in giant cell tumor of bone. Skeletal Radiol 1987;16:635-43. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Aledanni S, Alshahwani ZW, Hussein HR, Shihab M. Functional outcomes of sandwich reconstruction technique for giant cell tumor around the knee joint. Rawal Med J 2020;45:637-40. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Moaiyadi AH, Wankhede AK, Badole CM, Patond KR. Case of giant cell tumour of proximal tibia treated with intra-lesion curettage with adjuvant therapy and reconstruction with the sandwich technique fixation. Int J Res Orthop 2022;9:213-6. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gundavda MK, Agarwal MG. Extended curettage for giant cell tumors of bone: A surgeon’s view. JBJS Essent Surg Tech 2021;11:e20.00040. [Google Scholar]

- 14.Meena AM, Jain P, Dayma RL. Retrospective study of function outcome in giant cell tumor treated by sandwich technique with internal fixation. Int J Orthop Sci 2017;3:817-22. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Gaston CL, Bhumbra R, Watanuki M, Abudu AT, Carter SR, Jeys LM, et al. Does the addition of cement improve the rate of local recurrence after curettage of giant cell tumours in bone? J Bone Joint Surg Br 2011;93:1665-9. [Google Scholar]