Challenges faced post-TKA implant failure and how to address them.

Dr. Vishwajit Patil, Department of Orthopaedics, Robotics Arthroplasty and Sports Medicine Unit, Saishree Hospital, Pune, Maharashtra, India. E-mail: vishwajit.patil60@gmail.com

Introduction: Component failure is one of the most dreaded complications of any total knee arthroplasty (TKA) surgery. To tackle this, implant technology continues to evolve with the goal of increasing implant survivorship post-TKA surgery. It is estimated that about 20% of TKA revisions are due to mechanical aseptic loosening. Polyethylene insert wear has become an increasingly common finding at the time of revision surgeries. With this case report, we try to highlight the challenges faced during bilateral revision TKA and the use of both femoral and tibial augments to compensate for the bony osteolysis.

Case Report: A 69-year-old patient with unusual presentation of bilateral TKA (Exactech, Hiflex) failure 6 years post-surgery due to polyethylene wear. Three months following surgery, the patient had no complications and had satisfactory radiological, pain, and functional outcomes.

Conclusion: Although aseptic TKA failure due to polyethylene wear is an uncommon finding. Our case of the 69-year-old male with bilateral arthroplasty failure highlights the significance of the durability of polyethylene along with its wear and fracture resistance. It demonstrates that timely intervention with revision arthroplasty drastically improves pain, mobility, joint stability, and overall quality of life in these patients.

Keywords: Polyethylene wear, revision arthroplasty, total knee arthroplasty failure, augments, case report.

Total knee arthroplasty (TKA) has become one of the most frequently performed orthopedic procedures worldwide. It is estimated that more than 750,000 TKA cases were performed in 2014 [1]. In a study by Inacio et al. [2] in 2017, TKA number is projected to increase annually by 143% until 2050, translating to a projected volume of 1.5 million TKAs in the United States alone. The total number of knee revision surgeries is expected to grow by 601% by 2030 [3]. TKA component failure is one of the most dreaded complications of a replacement surgery. Therefore, implant technology continues to evolve to increase implant survivorship post-TKA surgery. A recent study demonstrated 96.1% and 89.7% survivorship at 10 and 20 years of TKA, respectively [4]. It is estimated that about 20% of TKA revisions are due to mechanical aseptic loosening [5]. Although many etiologies and factors can lead to mechanical loosening, one specific cause that has recently drawn more attention is the debonding of the tibial, femoral, or both components at the cement-implant interface [6]. One of the causes of this debonding is the wear of the polyethylene insert, which increases the stress on the cement-implant interface. When implant failure occurs, it can lead to persistent knee pain, recurrent effusion, and subsequent component migration, which may require partial or complete revision surgery [7]. This type of mechanical debonding may be challenging to diagnose, as radiographs often do not show clear evidence of aseptic loosening, and migration can be a late finding [8]. According to Rao et al., wear occurring at the interface between the polyethylene insert and the modular tibial baseplate has become an increasingly common finding at the time of TKA revision [9]. The longevity of the polyethylene tibial inserts also depends on the sterilization method. There have been increasing concerns regarding bearings sterilized with radiation in an inert gas may lead to oxidization in vivo and develop fatigue wear. This wear can be attributed to free radicals generated during sterilization with radiation [10]. At the same time, non-irradiated bearings may undergo more significant losses in thickness from routine burnishing since they lack the cross-linking that accompanies sterilization with radiation [10]. This case discusses an unusual presentation of bilateral TKA (Exactech, Hiflex) failure 6 years post-surgery due to polyethylene wear leading to implant loosening. With this case report, we highlight the challenges faced during the bilateral revision of TKA and the use of both femoral and tibial augments to compensate for the bony defect.

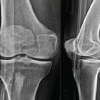

A 69-year-old, right-side dominant patient of Kellgren and Lawrence Pai et al. [11] grade 4 osteoarthritis (Fig. 1) underwent (Exactech, Hiflex) bilateral posterior stabilized primary TKA (Fig. 2) in a private hospital. The patient did not have any complaints and had been functioning well following his arthroplasty. 5 years after primary surgery, the patient presented with a history of bilateral knee pain (Right > Left) and joint instability, gradually increasing over the past 8 months. The patient also had difficulty walking with a painful limp. There was no history of any fall or trauma. The patient is a non-diabetic and normotensive individual. Surgical error as a possible causative factor was excluded because the patient had been functioning well after surgery.

On examination of both knees, effusion was noted along with joint line tenderness. Range of motion was 0–80° on the right knee and 0–110° on the left knee. Mediolateral instability was noted during the examination. The neurological and systemic examination revealed normal findings. The overall Visual Analog Scale (VAS) score [12] 3 months post-primary surgery was 1; this score increased significantly 9 to 6 years post-primary surgery. Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index (WOMAC) score [13] for the right knee three months post-primary surgery was 6 and 2 for the left knee. Six years post-primary surgery, the WOMAC score increased to 73 for the right knee and 45 for the left knee. For the right knee, three months post-primary surgery, the Forgotten Joint score (F.J. Score) [14] was 89.6 and 91.7 for the left knee. At the same time, F.J. score 6 years post-primary surgery was 14.6 for the right knee and 46.7 for the left knee.

Radiological findings

6 years post-operative X-ray (Fig. 3) findings, including knee standing A/P and lateral radiograph, revealed the femoral component loosening more on the right side. The A/P view of both knees revealed reduced joint space and polyethylene wear on the medial side. The lateral view indicated resorption of the posterior femoral condyles and debonding at the cement-bone interface more on the right than the left side.

Laboratory findings

The fluid culture from both knees showed no signs of infection. Gram and ZN stains were negative but revealed increased levels of neutrophils. Other basic investigations were normal except C-reactive protein, which was weakly positive.

Surgical procedure

Stage one

Right knee was operated on first, given being more symptomatically involved. Anterior midline skin incision was taken over the previous surgical scar. For arthrotomy, a medial para-patellar approach was used for the right knee. Synovitis was observed over the anterior femoral condylar surface. Both femoral and tibial implant loosening with polyethylene wear was noted. The polyethylene insert was detached from the tibial base plate using an osteotome. A loose femoral component, utterly detached from the femoral condylar surface, was noted. With the help of osteotome, an interface was created between the tibial bone and cement (Fig. 4). Diffuse osteolysis was noted over the medial femoral and tibial condyles. A synovectomy was done, and the fibrosis was released. The tibia and femoral preparation was done, and bony cuts were made. Flexion and Extension gap balancing using trial implants showed tight extension gaps. Hence, the bony cuts were revised, and the final gap balancing was done using trial implants.

Two 5 mm distal femoral augments were added to the trial femoral component to overcome the bony defect. Flexion and Extension gap balancing were re-done using trial implants. The final right knee implantation was done using a Maxx progressive constraint knee (PCK) freedom implant with femoral component size C with an extension stem of 15 × 75 mm. Two distal femoral augments and two posterior femoral augments of 5 mm each were used. The offset junction was set at 4mm. A tibial component of size 4 with an extension stem of 12 × 40 mm was selected and set at an offset junction of 4 mm. The bony defect on the tibial surface was built with bone grafts and cement. It must be noted that both the femoral and tibial canals were filled with cement before implantation. The final polyethylene insert of 17 mm PCK was implanted. All of the extravasated cement was meticulously removed before the hardening of the cement. A wound wash was given, and closure was done in layers over a suction drain after achieving adequate hemostasis.

Stage 2

The left knee was operated on 2 days following the right knee revision. Anterior midline skin incision was taken over the previously operated scar. Following medial para-patellar arthrotomy, the knee joint was exposed. The femoral component was not as loose as that of the right side. Synovitis was noted over the anterior femoral surface. The polyethylene insert and femoral and tibial components were removed. Polyethylene wear was also noted (Fig. 5). Osteolysis was observed over the medial femoral and tibial condyles. The defect over the medial tibial condyle was more significant than that of the opposite knee. Synovectomy was done along with fibrosis release. After taking the bony cuts, the tibia and femoral preparation were done.

Flexion and Extension gap balancing were done using trial implants and augments. Left revision TKA was done using Maxx PCK freedom implant. The final inserted femoral component was size C with a 12 × 40 mm extension stem. Two posterior femoral augments of 5 mm each were used, and the offset junction was set at 4 mm. The tibial component of size 4 was selected and fixed with an extension stem of 13.5 × 75 mm set at an offset junction of 4 mm. A tibial augment of 5 mm was attached to build the bony defect over the medial tibial condyle. The polyethylene insert of 14 mm PCK was inserted. The cementing technique was similar to that of the right knee. Wound wash was given, and a suction drain was inserted. Wound closure was done in layers after achieving hemostasis.

Intraoperative cultures taken from both knees were negative.

Postoperative result

The patient had a successful and uncomplicated postoperative rehabilitation and was released on postoperative day 5. All laboratory investigations were within normal limits at the time of discharge. Oral analgesics and physiotherapy facilitated a progressive recovery. For the initial 3 weeks, the patient used a walker for ambulation. Three weeks following surgery, the patient ambulated without any assistance. The patient resumed his occupation after 2 months of rehabilitation. Three months following surgery, the overall VAS score for pain was 0; the WOMAC score improved to 7 on the right knee and 4 on the left knee. Furthermore, the F.J. score was 82.4 for the right knee and 86.8 for the left knee. The postoperative X-ray of the bilateral knees acquired in standing A/P and lateral position revealed integrated components with a well-balanced joint line (Fig 6).

With final-stage knee osteoarthritis, TKA is the treatment of choice [15]. Patient selection and pre-operative diagnosis affect the outcome of aseptic TKA revision surgery [16]. Patients with aseptic failure can perform quite well if treated with proper surgical technique and appropriate implant selection [17]. According to Friedman et al., the functional improvement in stability, motion, and pain is significantly less after revision surgery for aseptic failure than after primary TKA [18]. Patients with aseptic failure but without knee stiffness have been noted to have a better outcome [16]. Meanwhile, patients who undergo revision TKA for stiffness instead of loosening or instability have inferior outcomes [19]. It is to be noted that aseptic revision TKA achieved a significantly better Knee Society Score and range of motion. In contrast, pain and functional scores were similar in septic and aseptic revision surgery [16]. This case is a peculiar presentation of polyethylene wear, leading to bilateral TKA failure. Orthopaedic practice has evolved from cement-on-cement articulating spacers to the routine use of metal-on-polyethylene spacers [20]. Therefore, the durability of the polyethylene, along with its wear and fracture resistance, are important factors for a successful arthroplasty outcome. For this patient, the revision of bilateral TKA with subsequent debridement and polyethylene component evaluation gave insight into the reasons for the catastrophic failure of the arthroplasty surgery. The bone loss due to osteolysis on the right and left knee was of type 2B as per the Anderson Orthopaedic Research Institute classification of TKA bone loss (Fig. 7) [21]. According to Rand in the research done at Mayo Clinic, Rochester, the knee scores drastically improved after the use of metal wedge augmentation for tibial bony defects [22]. Therefore, these osteolytic defects on tibial and femoral condyles in both right and left knees were successfully overcome using bone graft, metal augments, and cement mantle.

Although aseptic TKA failure due to polyethylene wear is an uncommon finding, our case of the 69-year-old male with bilateral arthroplasty failure highlights the significance of polyethylene’s durability, along with its wear and fracture resistance. It demonstrates that timely intervention with revision arthroplasty drastically improves pain, mobility, joint stability, and overall quality of life in these patients.

Research into the development of durable, wear-resistant, and fracture-proof polyethylene is essential for long-lasting TKA surgery. Tibial and Femoral augments must be used judiciously.

References

- 1.McDermott KW, Freeman WJ, Elixhauser A. Overview of Operating Room Procedures During Inpatient Stays in U.S. Hospitals, 2014. United States: National Library of Medicine; 2017. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Inacio MC, Paxton EW, Graves SE, Namba RS, Nemes S. Projected increase in total knee arthroplasty in the United States - an alternative projection model. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2017;25:1797-803. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Shichman I, Askew N, Habibi A, Nherera L, Macaulay W, Seyler T, et al. Projections and epidemiology of revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States to 2040-2060. Arthroplast Today 2023;21:101152. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Bayliss LE, Culliford D, Monk AP, Glyn-Jones S, Prieto-Alhambra D, Judge A, et al. The effect of patient age at intervention on risk of implant revision after total replacement of the hip or knee: A population-based cohort study. Lancet 2017;389:1424-30. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Delanois RE, Mistry JB, Gwam CU, Mohamed NS, Choksi US, Mont MA. Current epidemiology of revision total knee arthroplasty in the United States. J Arthroplasty 2017;32:2663-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Kutzner I, Hallan G, Høl PJ, Furnes O, Gøthesen Ø, Figved W, et al. Early aseptic loosening of a mobile-bearing total knee replacement. Acta Orthop 2018;89:77-83. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Sadauskas A, Engh C 3rd, Mehta M, Levine B. Implant interface debonding after total knee arthroplasty: A new cause for concern? Arthroplast Today 2020;6:972-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Arsoy D, Pagnano MW, Lewallen DG, Hanssen AD, Sierra RJ. Aseptic tibial debonding as a cause of early failure in a modern total knee arthroplasty design. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2013;471:94-101. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Rao AR, Engh GA, Collier MB, Lounici S. Tibial interface wear in retrieved total knee components and correlations with modular insert motion. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2002;84:1849-55. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Collier MB, Engh CA Jr., Hatten KM, Ginn SD, Sheils TM, Engh GA. Radiographic assessment of the thickness lost from polyethylene tibial inserts that had been sterilized differently. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2008;90:1543-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Pai V, Bell D, Knipe H. Kellgren and Lawrence system for classification of osteoarthritis. Radiopaedia Org. 2024 doi: 10.53347/rID-27111. [Google Scholar | PubMed | CrossRef]

- 12.Hawker GA, Mian S, Kendzerska T, French M. Measures of adult pain: Visual Analog Scale for Pain (VAS Pain), Numeric Rating Scale for Pain (NRS Pain), McGill Pain Questionnaire (MPQ), Short-Form McGill Pain Questionnaire (SF-MPQ), Chronic Pain Grade Scale (CPGS), Short Form-36 Bodily Pain Scale (SF-36 BPS), and Measure of Intermittent and Constant Osteoarthritis Pain (ICOAP). Arthritis Care Res 2011;63(Suppl 11):S240-52. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Gandek B. Measurement properties of the Western Ontario and McMaster Universities Osteoarthritis Index: A systematic review. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2015;67:216-29. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 14.Behrend H, Giesinger K, Giesinger JM, Kuster MS. The “Forgotten Joint” as the ultimate goal in joint arthroplasty: Validation of a new patient-reported outcome measure. J Arthroplasty 2012;27:430-6.e1. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 15.Patil VV, Sancheti PK, Patil K, Gugale S, Shyam A. Functional outcome of mechanical alignment in total knee arthroplasty surgery: A short-term cohort study at an Indian tertiary care hospital. Ind J Orthop 2023;58:11-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 16.Patil N, Lee K, Huddleston JI, Harris AH, Goodman SB. Aseptic versus septic revision total knee arthroplasty: Patient satisfaction, outcome and quality of life improvement. Knee 2010;17:200-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 17.Haas SB, Bostrom MP. Revision total knee arthroplasty due to aseptic failure. Am J Knee Surg 1996;9:91-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 18.Friedman RJ, Hirst P, Poss R, Kelley K, Sledge CB. Results of revision total knee arthroplasty performed for aseptic loosening. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1990;255:235-41. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 19.Pun SY, Ries MD. Effect of gender and preoperative diagnosis on results of revision total knee arthroplasty. Clin Orthop Relat Res 2008;466:2701-5. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 20.Gililland JM, Carlson VR, Fehring K, Springer BD, Griffin WL, Anderson LA. Balanced, stemmed, and augmented articulating total knee spacer technique. Arthroplast Today 2020;6:981-6. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 21.Parcells B. Osteolysis and Aseptic Loosening. Manasquan, USA; 2017. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 22.Rand JA. Bone deficiency in total knee arthroplasty. Use of metal wedge augmentation. Clin Orthop Relat Res 1991;271:63-71. [Google Scholar | PubMed]