Importance of early diagnosis, conservative management, and lifelong monitoring in Klippel–Trenaunay Syndrome to prevent complications and improve outcomes.

Dr. Shivam Tyagi, Department of Orthopaedics, Sri Ramachandra Institute of Higher Education and Research, Chennai, Tamil Nadu, India. E-mail: drtyagishivam@gmail.com

Introduction: Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS) is a rare congenital condition characterized by the classical triad of port-wine stains, varicosities, and hypertrophy of bone and soft tissue.

Case Report: A 5-year-old boy presented with swelling and varicose plaques on his right ankle with normal spine findings. He was diagnosed with KTS after relevant radiological investigations. Typically, management involves conservative measures such as compression stockings to alleviate edema due to chronic venous insufficiency, modern pneumatic compression devices, and occasionally surgical correction of varicose veins with lifelong monitoring.

Conclusion: This case report offers a concise overview of the clinical and pathological features of KTS, as well as its management strategies.

Keywords: Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome, port-wine stains, varicose plagues.

Klippel–Trenaunay syndrome (KTS or KT) is a rare condition characterized by a combination of soft tissue or bone growth, abnormalities in the blood vessels of the skin, as well as associated malformations in venous or lymphatic vessels. It is now referred to as capillary–lymphatic–venous malformation. Unlike arteriovenous malformations, which involve high blood flow, KTS involves low-flow vascular abnormalities. Typically, these abnormalities may manifest in a single limb, although multiple limbs can be affected in rare instances.

Recent research has established a connection between the development of KTS and somatic mutations in the phosphatidylinositol-4-5-bisphosphate 3-kinase, catalytic subunit (PIK3CA) gene. These mutations lead to the activation of phosphatidylinositol-3-kinase/protein kinase and subsequent cell overgrowth by disrupting the mTORC2 pathway [1,2]. These mutations typically occur during embryonic development, specifically affecting angiogenesis, which aligns with the observed characteristics of this syndrome.

KTS is now categorized within a broader group of overgrowth syndromes known as the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum. This spectrum encompasses various overgrowth syndromes that share similar clinical manifestations due to mutations in the PIK3CA gene. In addition, there have been rare reports of chromosomal translocations involving chromosomes 5–11 and 8–14 in some cases [3].

Accurate and early diagnosis of this syndrome is crucial, distinguishing it from similar-looking conditions such as Parkes–Weber syndrome – unilateral varicose veins, and hypertrophy with associated arteriovenous fistula, Proteus syndrome (the lesions exhibit a mosaic or random distribution across the body, gradually developing during childhood. After this period, the condition may either stabilize or continue to progress slowly. Associated features include kyphoscoliosis, macrodactyly, hyperostosis, asymmetric limb overgrowth, abnormal vertebral bodies, craniofacial abnormalities, and localized thickening of the skull) [4], Russell–Silver syndrome (chronic intrauterine growth retardation results in a reduction of all growth parameters, producing a “perfect miniature” baby, typically followed by catch-up growth within the 1st year of life. In contrast, late intrauterine growth retardation, particularly in post-mature fetuses, results in a thin, low birth weight baby with normal length and head circumference), Maffucci syndrome, congenital hemidysplasia with ichthyosiform erythroderma and limb defects syndrome, neurofibromatosis type 1 and triploid syndrome. This article reports a case and reviews the clinical manifestations, diagnostic workup, differential diagnosis, and management of KTS.

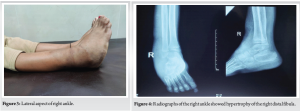

A 5-year-old boy presented with symptoms of pain and diffuse swelling over the right ankle region for a 2-week duration. The mother gives a history of a small swelling in the same region, which developed 1 week after childbirth. The swelling has progressed to the present status. On detailed physical examination, his heart rate was 95/min, which was regular, and blood pressure was 100/68 mmHg in the right upper arm. He had normothermia, with the absence of any jaundice, cyanosis, clubbing, and lymph node enlargement. He had an ill-defined, marked swelling over the right ankle region extending over the calcaneum. There was a 4 cm × 2 cm port-wine stain on the lateral aspect of the right ankle (Fig. 1).

Detailed examination showed multiple distinct red to bluish black papules present over the port-wine stain(Fig. 2,3,4). A few lesions were on the right distal third leg over the lateral aspect. Cavovarus deformity of the foot was noted along with forefoot in adduction.

Tenderness is present over the lateral malleolus. Range of motions at the ankle joint was restricted and painful, with fixed inversion deformity of 5°. Subtalar movements were found to be nearly normal. Spine examination was found to be normal. On measuring both lower limbs, they were found to be of equal length.

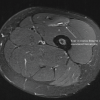

Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) of the right leg with angiogram showed slow flow vascular malformation involving the subcutaneous and muscle plane of the right leg and foot, with bony hypertrophy of the fibula(Fig. 5).The shape of the talus was abnormal, but there was no subtalar arthritis.

The MRI of the spine was done to rule out any intraspinal anomalies, as they are frequently associated with cavovarus deformities of the right foot. MRI spine showed no significant abnormality.

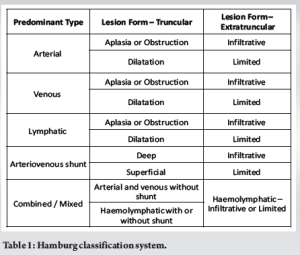

Clinically, the patient presented with swelling and bluish-purple skin discoloration, accompanied by prominent dilated veins on the lateral aspect of the right lower leg and ankle. The radiograph of the left leg revealed fibula hypertrophy. MRI of the right leg, including an angiogram, indicated a slow-flow vascular malformation. The combination of clinical presentation and imaging findings strongly suggested a diagnosis of KTS. The Hamburg classification system (Table 1) is used to categorize vascular anomalies based on their clinical and pathological features. KTS falls under the category of “Combined Vascular Malformations” under the Hamburg classification.

Given the incomplete understanding of KTS etiology, consensus on its treatment remains elusive. Sparse data exists on management, focusing on select aspects. Due to the complexity of affected structures, diverse patient issues, and varied age groups, a multidisciplinary approach is vital[5,6,7]. In most cases, patients are advised to wear either elastic or non-elastic compression stockings, with elastic stockings, in combination with psychological support, proving to be particularly effective [6,8]. A similar line of treatment was followed for this patient. These stockings are complemented by additional conservative approaches, such as regular leg elevation, physiotherapy, lifestyle adjustments, and maintaining proper hygiene. Treatment for conditions such as cellulitis and thrombophlebitis often involves the use of analgesics, antibiotics, and corticosteroids. Conventional sclerotherapy, although effective for small malformations, is ineffective in managing larger malformations [9]. Surgery is typically reserved for cases where patients exhibit severe symptoms. The effectiveness of surgical procedures relies on thorough pre-operative assessments of the deep venous system, often employing methods such as computed tomography arteriography to determine the extent of vascular issues and identify any arteriovenous fistulae that may lead to exacerbated symptoms, according to multiple authors.[10]

The patient requires consistent follow-up with medical professionals and periodic radiological monitoring of one of the affected

branches. Schoch et al. emphasize the elevated risk of orthopedic issues in patients presenting with lymphatic malformations and/or tissue hypertrophy, limb length discrepancy, angular deformities, scoliosis, and osteopenia/osteoporosis. Management often involves surgeries, with the most common being correction of limb length discrepancies and amputation of part or all of the affected limb. Other frequent procedures include arthroscopic debridement, debulking of venous or lymphatic malformations, total joint arthroplasty, and fixation of pathological fractures. [11].

Early involvement of an orthopedic specialist is critical in cases of limb-length discrepancy to determine the best timing for intervention to enhance symmetry by skeletal maturity. Discrepancies of <2 cm are generally managed without surgery. The rate of limb overgrowth in KTS varies, but significant progression of limb-length discrepancy is uncommon after age 12. Due to hypertrophy of the fibula, joint space narrowing can lead to the early onset of arthritis. Regular radiographs are important for monitoring and predicting the appropriate timing for surgical intervention [12].

The ideal operation in cases of hypoplasia or aplasia of the deep veins would be venous reconstruction, but this is a task for the future. Surgery may be considered right before skeletal maturation. Severe forms of KTS rarely occur. Fortunately, because of the benign course of this disease, the majority of these patients do not need surgery and do well with conservative therapy [13].

The current case was managed conservatively, focusing primarily on non-surgical methods. Emphasizing the importance of a multidisciplinary management team and regular follow-up is crucial to preventing complications that could affect the patient’s prognosis.

KTS is a rare but complex condition that requires early diagnosis and a multidisciplinary approach for effective management. While conservative measures are often sufficient for many patients, surgical interventions may be necessary in severe cases. Regular follow-up and monitoring are critical to managing symptoms and preventing complications. Early intervention by specialists in orthopedics and vascular surgery is vital to ensuring optimal outcomes for patients with this syndrome.

Klippel–Trenaunay Syndrome (KTS) is an uncommon congenital vascular anomaly defined by a triad of capillary malformation (port-wine stain), venous abnormalities, and soft tissue or bone overgrowth. Prompt and accurate identification, particularly in differentiating it from similar overgrowth conditions, is vital for timely management. Non-surgical approaches, including compression therapy, are the first line of treatment, with surgical options considered for more advanced or symptomatic cases. Ongoing multidisciplinary evaluation and follow-up play a key role in detecting complications early and coordinating appropriate orthopedic and vascular care for improved patient outcomes.

References

- 1.Vahidnezhad H, Youssefian L, Uitto J. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome belongs to the PIK3CA-related overgrowth spectrum (PROS). Exp Dermatol 2016;25:17-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Martinez-Lopez A, Salvador-Rodriguez L, Montero-Vilchez T, Molina-Leyva A, Tercedor-Sanchez J, Arias-Santiago S. Vascular malformations syndromes: An update. Curr Opin Pediatr 2019;31:747-53. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Sharma D, Lamba S, Pandita A, Shastri S. Klippel-trénaunay syndrome - a very rare and interesting syndrome. Clin Med Insights Circ Respir Pulm Med 2015;9:1-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Jamis-Dow CA, Turner J, Biesecker LG, Choyke PL. Radiologic manifestations of Proteus syndrome. Radiographics 2004;24:1051-68. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Lee A, Driscoll D, Gloviczki P, Clay R, Shaughnessy W, Stans A. Evaluation and management of pain in patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: A review. Pediatrics 2005;115:744-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Noel AA, Gloviczki P, Cherry KJ, Rooke TW, Stanson AW, Driscoll DJ. Surgical treatment of venous malformations in Klippel-Trénaunay syndrome. J Vasc Surg 2000;32:840-7. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Gloviczki P, Driscoll DJ. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: Current management. Phlebology 2007;22:291-8. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Gloviczki P, Stanson AW, Stickler GB, Johnson CM, Toomey BJ, Meland NB, et al. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: The risks and benefits of vascular interventions. Surgery 1991;110:469-79. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Redondo P, Bastarrika G, Sierra A, Martínez-Cuesta A, Cabrera J. Efficacy and safety of microfoam sclerotherapy in a patient with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome and a patent foramen ovale. Arch Dermatol 2009;145:1147-51. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Lindenauer SM. The Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: varicosity, hypertrophy and hemangioma with no arteriovenous fistula. Ann Surg 1965;162:303-14. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 11.Schoch JJ, Nguyen H, Schoch BS, Anderson KR, Stans AA, Driscoll D, et al. Orthopaedic diagnoses in patients with Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. J Child Orthop 2019;13:457-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 12.McGrory BJ, Amadio PC. Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome: Orthopaedic considerations. Orthop Rev 1993;22:41-50. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 13.Gloviczki P, Hollier LH, Telander RL, Kaufman B, Bianco AJ, Stickler GB. Surgical implications of Klippel-Trenaunay syndrome. Ann Surg 1983;197:353-62. [Google Scholar | PubMed]