In case of myositis ossificans traumatica, a complete surgical excision of the lesion followed by ROM exercises gives a satisfactory outcome.

Dr. Deepak Kumar, Department of Orthopaedics, MLN Medical College, Prayagraj, Uttar Pradesh, India. E-mail: deep7991@gmail.com

Introduction: Myositis ossificans traumatica (MOT) of the elbow is a rare entity in children. It is a self-localized tumor-like lesion of the elbow causing ankylosis due to humeroulnar bridging. It is a complication arising due to a muscle contusion injury.

Case Report: We report a case of an 8-year-old female who presented with a 2-year history of a fixed elbow and a palpable bony mass. The examination confirmed a confined bony mass on the anterior aspect and ankylosis of her left elbow. On confirmation of the diagnosis, an en bloc excision was performed. Follow-up every 2 weeks for the first 3 months, then once a month for the next 6 months, and finally once every 6 months for the next 4 years. The affected limb functioned well, with no sign of recurrence.

Conclusion: MOTs of the elbow in children are a rarity, and excision of the lesion without delay is an effective management strategy for a satisfactory outcome.

Keywords: Bridging myositis ossificans traumatica, elbow joint, ankylosis.

Myositis ossificans (MO) is an uncommon complication of trauma and surgery, defined as ossifying changes in a non-osseous tissue, such as muscles. MO traumatica (MOT) is a kind of self-localized, benign, and tumor-like lesions often seen in adults, with approximately 75% of cases caused by trauma [1]. Moreover, it is not very common among children. A significantly large MOT causing ankylosis of the elbow is even rarer. When it occurs around a joint, it can cause ankylosis, leading to complete dysfunction of the joint. Clinical and radiological appearances may mimic a sarcomatous neoplastic process [2]. Although it is described in most parts of the body, bridging types of MOT involving elbow joints are rarely reported.

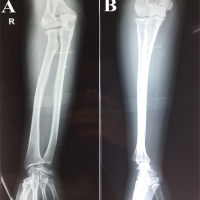

An 8-year-old female child presented with a 2-year history of a fixed elbow with almost no movement and a palpable bony mass. She had sustained significant trauma to her left elbow, followed by indigenous treatment in the form of native massage and slab for 2 months before the onset of symptoms [3]. Although it was her non-dominant limb, she had difficulties with daily activities such as clothing herself and tying shoelaces [4]. A clinical examination showed bony ankylosis and a fixed elbow with minimal range of movement at the elbow to be 0–10°. A palpable diffuse bony mass was present on the anterior aspect of the elbow, with the margins tapering to the corresponding muscles. No distal neurovascular compromise or limb length discrepancies were detected. Due to bone hyperplasia early during the disease, such masses may be mistaken for soft-tissue tumors or osteosarcomas. Soft-tissue tumors or osteosarcomas are often accompanied by periosteum hyperplasia, bone-cortex destruction, and unclear borders on X-ray radiography, which is not seen in this case. Thus, the mass was not a tumor (Fig. 1 and 2).

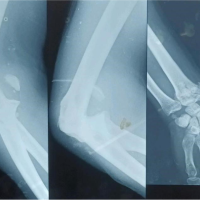

The procedure was performed under regional anesthesia with the patient supine on the OT table and the limb abducted at the shoulder. The anterolateral approach of the elbow was used and modified based on ease and the need for convenience during the surgery. An 8-cm curvilinear incision with a proximal plane between brachialis and brachioradialis and distally between brachioradialis and pronator teres was used (Fig. 3). Subcutaneous tissue and deep fascia were incised in line with the skin incision. Supinator muscle and biceps tendon insertions were not sacrificed. The posterior interosseous nerve was protected, which is one of the major surgical risks in this type of approach. Other surgical risks include protection of the anterior branch of the profunda brachii artery and the radial recurrent artery. The distal biceps tendon must always be safeguarded during the en bloc excision. Further, with deep blunt finger dissection, both ends of the abnormal bone were identified and exposed adequately. The mass was excised completely after detaching it from the humerus proximally and the ulna distally. Electrochemical cauterization was performed at both the ends followed by local steroid injections. The elbow was mobilized intraoperatively. The excised specimen was sent for histopathological examination, which was confirmed later on. Neurovascular status was good postoperatively, that is, no neuropraxia or other neurological complications was encountered postoperatively. No signs of infection were noted, and the post-operative wound healed well. X-ray radiographs after surgery showed complete excision of the lesion (Fig. 4).

The patient was given a slab of elbow in extension for 7 days. The patient was kept on a range of motion (ROM) brace with intermittent ROM exercise (90° of elbow flexion to 180° of elbow extension) (Fig. 5) and reviewed every 2 weeks for the first 3 months and once monthly thereafter for up to 6 months, followed by once every 6 months for up to 4 years. The patient regained elbow joint movement with the flexion and extension of approximately 120° (range 0–120°). The Broberg–Morrey score was 97 of the affected limb on 6 weeks of follow-up. There was no indication of a recurrence, and the affected limb functioned normally (Fig. 6 and 7).

MO is an uncommon complication of upper limb trauma, especially after fractures around the elbow, which are even rarer [5]. This phenomenon of unknown etiology occurs after damage to muscle, with subsequent proliferation and ossification of connective tissue and its differentiation into a mature bone-like mass [6,7]. Muscle injury was considered the main cause. Muscle damage stimulates the production of prostaglandins that recruit inflammatory cells at the site of injury and promote ectopic bone formation. MOT can have various morphological presentations, of which the bridging type of MO causing ankylosis to the elbow is of a rare variety. To the best of our knowledge, very few such cases have been reported to date, of which two are very similar to ours [8,9]. Kanthimathi et al. [8] reported a 13-year-old boy with MO in his left elbow, which was immobilized for 4 weeks because his left upper limb suffered significant trauma. The stiffness of the elbow lasted for 14 months. We also believe that such cases should be assessed clinico-radiologically and operated on immediately after the clinical assessment, without delay, to achieve optimum functional range of motion, but not to forget that progression of the disease should have completely halted. Conner et al. proposed that surgical intervention should only be initiated when the disease has completely halted [10].

Surgical dissection in such cases may not follow the hand-to-hand rule of anatomical dissection because of abnormal bony landmarks and soft tissue envelopes. Our intraoperative findings confirmed involvement of the brachialis muscle, which arises from the antero-inferior part of the humerus and inserts at the ulnar tuberosity. It is a complete resection of the lesion, which is more important than the anatomy of dissection, and the surgeon has the freedom to modify his plan of dissection based on the ease of the surgery and his convenience.

The result is optimal in terms of range of motion if the post-operative rehabilitation protocol is followed appropriately and timely. Surgical excision produced a satisfactory outcome, and undue delaying of surgery has no benefit.

References

- 1.Li PF, Lin ZL, Pang ZH. Non-traumatic myositis ossificans circumscripta at elbow joint in a 9-year old child. Chin J Traumatol 2016;19:122-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 2.Benkada S, Jroundi L, Jaziri A, Elkettani N, Chami I, Boujida N, et al. Myositis ossificans circumscripta: A case report. J Radiol 2006;87:317-9. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 3.Chadha M, Agarwal A. Myositis ossificans traumatica of the hand. Can J Surg 2007;50:E21-2. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 4.Walczak BE, Johnson CN, Howe BM. Myositis ossificans. J Am Acad Orthop Surg 2015;23:612-22. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 5.Hartigan BJ, Benson LS. Myositis ossificans after a supracondylar fracture of the humerus in a child. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ) 2001;30:152-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 6.Ackermann LV (1958) Extra-osseous localized non neoplastic bone and cartilage formation (so called myositis ossificans). J Bone Joint Surg Am 40:279–298 [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 7.Aneiros-Fernandez J, Caba-Molina M, Arias-Santiago S, Ovalle F, Hernandez-Cortes P, Aneiros-Cachaza J. Myositis ossificans circumscripta without history of trauma. J Clin Med Res 2010;2:142-4. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 8.Kanthimathi B, Udhaya Shankar S, Arun Kumar K, Narayanan VL. Myositis ossificans traumatica causing ankylosis of the elbow. Clin Orthop Surg 2014;6:480-3. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 9.Chen J, Li Q, Liu T, Jia G, Wang E. Bridging myositis ossificans after supracondylar humeral fracture in a child: A case report. Front Pediatr 2021;9:746133. [Google Scholar | PubMed]

- 10.Sferopoulos NK, Kotakidou R, Petropoulos AS. Myositis ossificans in children: A review. Eur J Orthop Surg Traumatol 2017;27:491-502. [Google Scholar | PubMed]